Eileen McKeating, Kaitlin Mulcahy, Gloria Andrade, and Corinne G. Catalano, Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health at Montclair State University

Abstract

Relationships are the foundation of the early childhood professional’s work with infants and young children in their care. Caregiver behavior deeply influences a child’s capacity to cope with stress. Supporting caregivers emotionally allows them to be more regulated and available to infants, children, and families. The stress of COVID-19 has undoubtedly impacted the psychological health of many, most notably, the early childhood education (ECE) workforce who are disproportionately women of color. This article will focus on facilitated groups for Spanish-speaking providers and will outline socioculturally attuned support, provided to underserved early childhood professionals in private ECE establishments.

The COVID-19 pandemic placed a tremendous emotional strain on the human services workforce. A disproportionate impact was experienced by the private early childhood education (ECE) industry and early childhood educators, especially those who remained open during the stay-athome order (Yoonjeon et al., 2022). ECE professionals serving families during this pandemic were the “workers behind the workers,” and they risked their health and the health of their families to care for children and to keep the economy open (Tracey et al., 2020). Directors, teachers, and staff had to invent new routines and procedures to keep themselves and the children safe. Regulations involving staff-to-child ratios and social distancing necessitated structural and procedural changes including rearranging rooms, realigning staff, and, most notably, reducing enrollment capacity. Program directors and owners in both center- and home-based settings faced enrollment challenges, staffing issues, and increased operating costs due to required purchasing of cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment. The COVID-19 pandemic levied emotional costs as well. The “indefinite uncertainty,”—fear of the unknown along with learning new coping strategies—was anxiety-provoking (Osofsky, 2020) and impacted the emotional well-being of many in the early childhood workforce (Nagasawa & Tarrant, 2020). Additionally, the initial stay-at-home order created a tear in the fabric of the community that often exists within center-based ECE. The ECE workforce often works shoulder-to-shoulder with colleagues every day in centers that become like a family. Sudden closure due to the initial stay-at-home order drastically changed the connections, emotional climate, and culture of community that often characterizes the ECE field.

Response to COVID-19: Conversations for Connection, Comfort, and Calm

Similar to many helping professionals at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the staff at our Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health (CAECMH) at Montclair State University were working together to quickly pivot programming to address the multitude of concerns and stressors that were emerging, while concurrently reimagining our provision of consultation, coaching, and training services through virtual methods that we had not used before. Primary in our thinking was the emotional well-being of the early relational and developmental health workforce, particularly the ECE workforce who initially were made abruptly separate from their professional community and then were asked to return to work at a time that was frightening and uncertain, in a time frame that did not allow for the establishment of clear protocols and procedures that needed to adapt to the constantly changing public health crisis.

The question at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic for CAECMH became “How can we support the adults, specifically those working in ECE, in the midst of the pandemic so they could be emotionally present for the young children in their care?” Research has shown that supporting caregivers’ psychological well-being and addressing their stress are prudent for their benefit as well as for the children in their care (e.g., Hamre et al., 2014; Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Jeon et al., 2019), and the staff at CAECMH focused on creating programming that would be emotionally supportive to the workforce. Evidence also suggests that the quality of ECE is closely linked to characteristics of the adult providing care, including their well-being (e.g., Howes & Sanders 2006; Pianta et al., 1995; Whitaker et al., 2015). We operated with the concept of co-regulation in mind, recognizing that the ability to provide attuned care is foundational for healthy relational, emotional, and social development in infants and young children (Stern, 1985) and caregiving adults also need to be felt-with and attuned-to (Siegel & Hartzell, 2003). Using these foundational theories, CAECMH created a program called Conversations for Connection, Comfort, and Calm, which soon became known to the workforce as the 3Cs.

Group Purpose and Process

The purpose of the initiative was to bring the early relational and developmental health workforce together in short-term virtual groups that had no other agenda than what was communicated in the name of the initiative: creating a space of connection, comfort, and calm in community with other members of the workforce. Our hope was that these groups would address the negative effects of isolation and uncertainty of the pandemic and provide a place for reflection and discussion. As such, sessions were purposely unstructured, allowing opportunities for the conversation to flow from the group. Facilitators were provided the freedom to craft the activities of the sessions in the way that felt most authentic to the facilitator. There were some similarities among the sessions, including mindfulness activities, breathwork, reflections about quotes, multimedia or a piece of music, and resource sharing. Facilitators also provided open space for checking in with participants’ emotional states. Participants were encouraged to engage in self-care and were offered strategies to support their colleagues and other members of the early childhood workforce, as well as the children in their care. All 3Cs facilitators had experience providing reflective practice or reflective supervision/ consultation groups in the past, and they were supported by supervisors at CAECMH through monthly facilitator groups.

Group Structure

We structured the initiative to be short-term, initially not knowing how long the COVID-19 pandemic would last. Groups met for 6 consecutive weeks with the same facilitator for no more than 1 hour each week. Participants were encouraged but not required to attend all six sessions. After the 6-week session completed, new groups were established, and participants were welcome to sign up for multiple rounds of groups. Groups were offered virtually, largely because of the need for social distancing, but also to provide equitable access to the initiative. Consistent with research into virtual platforms, virtual reflective groups provide the ability to overcome typical obstacles such as time, cost, geographical location, access to transportation, or quality personnel and often offer a more efficient means of meeting (Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, 2020; McCormick et al., 2020). Although our agency was operating a handful of virtual reflective groups pre-pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic made virtual reflective groups more conventional, allowing people to create and enhance professional connections (McCormick et al., 2020). Groups were offered in a structure that was meant to be most optimally attuned to the lifestyles and needs of the participants. Groups were held at multiple times of the weekday, evenings, and on weekends to accommodate family and work schedules and participant context. Groups were offered in both English and Spanish to meet the needs of the multilingual workforce. Up to three groups at a time were offered in Spanish by bilingual Spanish-English and bicultural facilitators, understanding that equity of access to culturally and linguistically sensitive supports is needed, most particularly in times of hardship.

Identifying Needs and Disparities

Early in the first round of 3Cs offerings, it became clear that the Spanish-speaking groups were proceeding differently than the English-speaking groups. First, although guidance was to limit group size to 15 participants, the Spanish-speaking groups were consistently overenrolled to between 25 and 30 participants because of the overwhelming need and interest of the members. Often, group members would invite their

colleagues and friends who did not have access to registration and the group would grow. Lack of access could have been due to centers not having an email address, not being on our contact lists, or simply missing the email invitation. They also may have needed additional prompting from colleagues to initially join. Second, the rate at which the Spanish-speaking participants were themselves contracting COVID-19, or had immediate family members testing positive for the virus, appeared drastically disparate from the participants of the English-speaking groups. Participants were joining the 3Cs group from their beds and even from the hospital while sick. COVID-19 was prevalent in our Spanish-speaking community, which is consistent with data showing that women of color have most acutely felt the impacts of COVID-19 and the ECE workforce (National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2020) but despite illness, members wanted to participate in the virtual groups.

The early childhood education workforce often works shoulder-to-shoulder with colleagues every day in centers that become like a family. Photo: ZERO TO THREE

Across the U.S., Black and Latina ECE providers are more likely to test positive for COVID-19 than White providers. This disparity is likely a result of inequities in health care access (Gilliam et al., 2020) and underlying chronic health conditions (Child Care Aware, 2019; Linnan et al., 2017). COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths disproportionately affected Blacks and Latinos (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020), including for ECE workers of color. There was an overwhelming sense of gratitude for the existence of the 3Cs group, with many participants sharing that they had very little opportunity to connect with others in their profession and had almost no access to professional development in their native language. Because of these differences between the English-speaking and Spanish-speaking groups, we chose to learn more about the experience of Spanish-speaking participants, most of whom were ECE providers. The results that follow tell the story of the Spanish-speaking 3Cs groups.

Participant Feedback

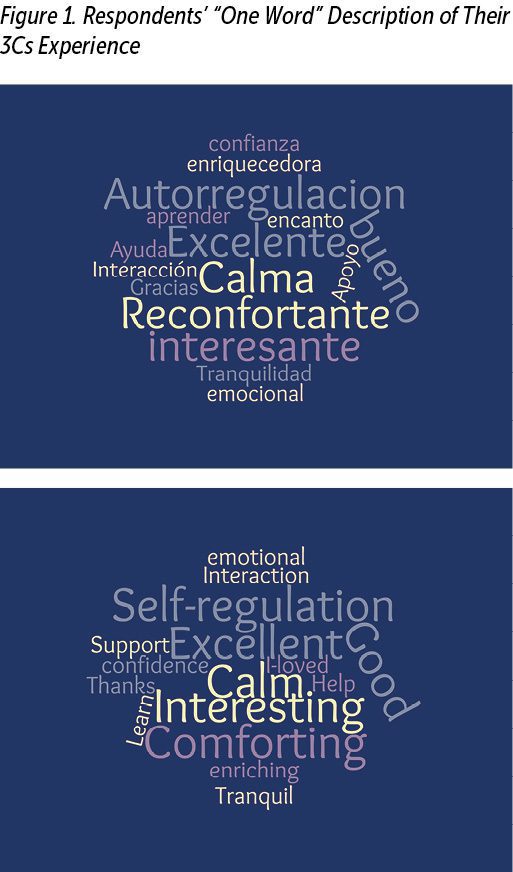

A survey was developed to better understand the participants’ experience of the groups. Data collection took place over 2 weeks in November 2020. A total of 29 individuals in the Spanish-speaking groups responded to all of the questions in the survey. Survey respondents were predominantly family care providers (n = 13, 45%) teaching assistants (n = 8, 28%), technical assistance specialists (n = 5, 17%), and early intervention providers (n = 3, 10%). The vast majority (86%) were working on site while the remaining 14% worked remotely at the beginning of the pandemic. Survey respondents had been working in the infant and early childhood field from anywhere from 2 to 50 years with an average of 12 years of experience. Respondents were asked to rate their experience of the 3Cs group between April and August of 2020 on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from extremely positive to extremely negative. The vast majority (86%) rated the experience as extremely positive. Respondents were also asked to provide one word to describe their experience of the 3Cs. Responses are shown in the figures, in Spanish and translated to English (see Figure 1). The words that were used more frequently appear larger in the figures, the smallest words were typed into the survey one time. The early childhood education workforce often works shoulder-to-shoulder with colleagues every day in centers that become like a family.

Emerging Themes

Participants were also asked for open-ended feedback or comments on their experience of participating in the groups. More than one third of the respondents in the Spanish-speaking groups chose to provide additional open-ended comments (n = 14, 39%). Open-ended comments revealed four themes of experience, many of which are in line with the purpose of the group: (1) the groups helped participants connect with others, (2) the groups allowed for a space that felt comfortable enough to express vulnerabilities and struggles, (3) the groups helped members find calm and feel regulated in times of stress, and (4) the groups helped participants feel valued.

Find Connection

The first theme expressed by participants was the opportunity for connection with other professionals. One participant shared that she, “conectada con mis compañeras que pueden entender lo que esta nueva norma ha sido y sigue siendo...”. Translation: “I connected with my peers who can relate to what this new norm has been and still is...”. Another participant expressed, “Estos grupos nos dicen que no estamos solas.” Translation: “These groups tell us that we are not alone.” Another participant also mentioned the benefit of connection and added that she enjoyed connecting with others with slightly different roles than her own, saying, “Disfruté la oportunidad de conectarme con un grupo diverso de personas que trabajan en el mismo campo en diferentes roles.” Translation: “I enjoyed the chance to connect with a diverse group of people working in the same field in different roles.” These comments served to validate the initial purpose of the group, which was to foster emotional connection at a time of social distance. The sense of belonging was an important aspect of the 3Cs groups, as comments reflected a shared experience and closeness. These participants acknowledged the connections made because of the group which helped them feel more connected in social relationships at a time of increased isolation.

Share Vulnerability

The second theme that arose from participant feedback was the opportunity provided by the group that allowed participants to share struggles and seek comfort. As one participant remarked, “Encontré en el grupo un lugar que me permitió ser vulnerable.” Translation: “I found in the group a place that allowed me to be vulnerable.” Another participant echoed this sentiment saying, “La participación en estos grupos me ayudó mucho a permitirme ser vulnerable.” Translation: “Participation in these groups helped me a lot to allow myself to be vulnerable. Participants also mentioned the comfort in the group that was established so that they could express their struggles and fears that were rising during the pandemic. As shared by one participant, “Fue reconfortante tener un espacio seguro para discutir las luchas de liderazgo durante una pandemia.” Translation: “It was comforting to have a safe space to discuss the struggles of leading during a pandemic.” Shared native language may have contributed to the participant’s confidence in opening up with each other and creating a climate of comfort in the group. Anecdotally, participants reported that this was the first opportunity they had been offered to receive support with their peers in their native language. Participants expressed appreciation that they were able to experience the 3Cs in Spanish. The groups were able to experience emotional closeness and attunement in a way that might not have been available had the group not been in their native language. Previous literature has suggested that learning experiences delivered in a participant’s language of origin are more successful for the participant (Caldwell-Harris, 2015). This is especially true for reflective experiences, as research has found that native language will carry stronger emotional resonances and is preferred for expressing emotional language via social interactions (Caldwell-Harris, 2015), as there are variables that affect the force of emotional words in the second language (Ferré et al., 2010). The 3Cs groups appeared to provide a space of comfort for participants to share their vulnerability and sense of uncertainty with one another with the confidence that they would be understood in their own language.

The sense of belonging was an important aspect of the 3Cs groups, as comments reflected a shared experience and closeness. Photo: Light and Vision/shutterstock

Manage Stress

The third theme that arose from participant feedback was the opportunity provided by the 3Cs group to find calm and to regulate their stress reactions to the increased worry brought on by the pandemic. This sentiment is illustrated by the following quote: “Esto era muy necesario, especialmente durante estos tiempos difíciles.” Translation: “This was so needed, especially during these rough times.” Coping strategies, including self-regulation and calming tools, were cited as useful learning by participants. One participant remarked that the groups helped her “…a buscar medios, opciones y oportunidades para contribuir a regularizarme en medio del caos y la incertidumbre que estamos viviendo.” Translation: “…to look for means, options, and opportunities to contribute to regulate myself in the midst of the chaos and uncertainty we are experiencing. Another participant wrote, “Me gustó todo el grupo, pero los ejercicios de respiración fueron especialmente útiles y continúo incorporándolos a mi rutina diaria.” Translation: “I liked the whole group but the breathing exercises were especially helpful and I continue to incorporate them into my daily routine.” Participants also mentioned that learning regulation strategies in the group served to help their own anxiety about the pandemic. One of the participants reported, “El grupo 3Cs me ayudó mucho a regularme, porque entré en un proceso de pánico al comienzo de la pandemia.” Translation: “The 3Cs group helped me greatly to regulate, because I entered a panic process at the beginning of the pandemic.” According to Kabat-Zinn (2003) and others, reflection and mindfulness practice help individuals manage stress by developing the capability to pay attention to their thoughts and feelings without judgment. The 3Cs participants reported that they used these newly acquired self-regulation skills, including the ability to intentionally foster calm or co-regulate others, by sharing their state of being as a means of support for colleagues in the early childhood workforce. As the adage states “calm begets calm,” and the 3Cs groups appeared to assist participants in accessing their own calm from the group so that they could then lend their calm to others in their care.

Participants shared that they felt considered and seen because of the opportunity to gather with others who spoke their language and held similar professional roles. Photo: fizkes/shutterstock

Feel Valued

The final theme that emerged was one that was unexpected to facilitators, as it was not part of the intended purpose of enhancing connection, comfort, and calm. Participants shared that the groups helped them feel valued. One participant shared those words exactly, “Me sentí valorada.” Translation: “I felt valued.” Another shared that the groups made them feel appreciated, “…que somos una comunidad importante para la sociedad en esta labor de amor que llevamos a cabo por nuestros niños y niñas.” Translation: “…that we are an important community for the society in this labor of love that we carry out for our boys and girls.” By “we,” this participant was referring to the Spanish-speaking ECE provider community, who traditionally had little access to professional development or reflective activities in their language of origin, and who tend to be more isolated as a professional community. Participants shared that they felt considered and seen because of the opportunity to gather with others who spoke their language and held similar professional roles. They also expressed thanks that a group in their language would be offered to them at all, and felt gratitude at being included in this initiative as in this quote, “Les agradezco esta gran oportunidad de participar y que por favor se les siga enseñando.” Translation: “I thank you for this great opportunity to participate and that they please continue to be taught.” While the outcome of participants feeling valued was not expected by the group developers or facilitators, it can be understood through previous literature that suggests that a sense of value and a sense of self progresses from the experience of attunement, or being feltwith (Siegel & Hartzell, 2003).

In the case of the Spanish-speaking 3Cs groups, the interpersonal attunement created by the group was supported by sociocultural attunement in the structure of the offering. Sociocultural attunement has been defined as “practice that is aware and responsive to the intersections of societal context, culture, and power in client experience and positioned to promote equity” (Knudson-Martin et al., 2019, p. 47). The challenges that the pandemic posed to this underserved community required that facilitators attuned to the intersections of culture, context, and positionality of group participants. The clear disparity of experience that began to emerge soon into the pandemic between the English-speaking and Spanish-speaking groups also meant that facilitators explicitly addressed the dynamics of disproportionality, discrimination, and differential power to help discuss the impact of the pandemic on this population. Additionally, the facilitators were humbled, hearing participants’ consistent gratitude for the creation of a space that felt socioculturally attuned to their needs and their strengths, and that allowed them to feel heard and understood. Even outside the context of the pandemic, the Spanish-speaking 3Cs group participants appeared to feel interpersonally and socioculturally attuned with, as the realities of their day-to-day work as ECE providers was seen, respected, and celebrated. It is likely this multileveled attunement resulted in the participants feeling valued by the 3Cs offering.

On the basis of participant feedback, it appears that the 3Cs, in fact, delivered on the tenets of connection, comfort, and calm. The 3Cs succeeded in providing a space that permits group members to feel connected, supported and fulfilled, which is suggested as essential in difficult times (Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, 2020; DeSchryver, 2020; McCormick et al., 2020). Participants overwhelmingly felt the 3Cs groups were beneficial in fostering relationships cemented in trust and providing a safe space for support. Respondents reported that meeting at a routine time aligned with their family and work schedules and talking with a group of people going through the same or similar experiences in their native language helped them cope with the negative impact of the stress of the pandemic. Participants reported that connections and sense of belonging lowered stress levels at a time that their lives were saturated with new demands.

Conclusion

The messages shared by participants indicated that relationships mattered and that joining the groups supported the participants’ emotional well-being. Additionally, participants shared that they felt seen, validated, and valued based on the multilayered interpersonal and sociocultural attunement experienced by the group meeting their needs of emotional attunement, and language, accessibility, availability, and community, so much so that many of the 3Cs participants shared the desire captured by one member’s hope that the 3Cs “…por favor continúen enseñándonos.” Translation: “…please continue to be taught.”

Fortunately, we have been able to follow the needs of the workforce, and 3Cs groups in Spanish and English have run continuously since the start of the pandemic to the present, and participation remains robust and engaged. Our experience with these groups has demonstrated the need for socioculturally attuned support for the often underserved workforce. While it is unfortunate that a global pandemic was the impetus to embed this program in the system, we now see it as one of the “COVID-tunities” that emerged during some of the most tumultuous times in recent history. See Box 1 for suggested guidelines to institute similar programming for the early relational and developmental health workforce in your communities and to enhance your conversations for connection, comfort, and calm. We know that they have made us better consultants, coaches, trainers, clinicians, and members of our human community.

Box 1. Suggestions for Practice in Designing Culturally Responsive Peer Support Groups

The following guidelines may be useful in establishing groups to support the early childhood education workforce in your community:

- Offer a variety of days and times from which participants can choose to attend, depending on their work and family obligations.

- Have a consistent meeting time for each session.

- Ask participants to commit to the group for a term of six sessions in order to foster trust and relationship among participants.

- Strive to engage multidisciplinary groups of participants with various roles (e.g., early childhood educators, family child care providers, technical assistance specialists, early interventionists) to gain perspectives across disciplines.

- Facilitate support groups in the native language of participants.

- Meet monthly with facilitators to debrief, reflect on the experience, and support each other

Talking with a group of people going through the same or similar experiences in their native language helped them cope with the negative impact of the stress of the pandemic. Photo: krakenimages.com/shutterstock

Authors

Eileen McKeating, PhD, is currently the research associate at the Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health at Montclair State University. Dr. McKeating is responsible for research initiatives and program evaluation for the Center’s many federal-, state-, and foundation-funded projects. Her publications include articles on preschool expulsion, clinical judgment, and topics related to autism spectrum disorder.

Kaitlin Mulcahy, PhD, LPC, IMH-E®, serves as the director of the Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health at Montclair State University. Dr. Mulcahy is informed by work experiences as an infant, early childhood, and family therapist within the sectors of child protection, early intervention, and community mental health. She received a doctorate in family science and human development from Montclair State University, is a licensed professional counselor, and is endorsed as an Infant Mental Health Clinical Mentor®.

Gloria Andrade, PhD, IMH-E®, is lead early childhood consultation specialist at Montclair State University’s Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health. Dr. Andrade is responsible for providing professional formation, family education, and infant and early childhood mental health consulting to relevant community partners.

Corinne G. Catalano, PhD, IMH-E®, is the assistant director for consultation services at Montclair State University’s Center for Autism and Early Childhood Mental Health. She is the project manager for the New Jersey Inclusive Education Technical Assistance project funded by the New Jersey Department of Education. Dr. Catalano is a member of the New Jersey State Interagency Coordinating Council (SICC) for Early Intervention and serves as chair of the SICC Personnel Preparation Committee.

Suggested Citation

McKeating, E., Mulcahy, K., Andrade, G., & Catalano, C. G. (2023). Culturally responsive peer support groups during COVID-19 for the Spanish-speaking early childhood education workforce. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 43(3), 26–32.

References

Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (2020). Guidelines for beginning and maintaining a reflective supervision/consultation relationship via distance technology. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5884ec2a03596e667b2ec631/t/5ec58399b2ae022884fd28ae/1590002588308/Alliance_Virtual_RSC_2020_FINAL.pdf

Caldwell-Harris, C. (2015). Emotionality differences between a native andforeign language: Implication for everyday life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(3), 214–219.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Risk of severe illness or death from COVID-19. www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Child Care Aware. (2019). The US and the high price of child care: An examination of a broken system. www.childcareaware.org/our-issues/research/the-us-and-the-high-price-of-child-care-2019

DeSchryver, J. (2020). Therapeutic presence: The critical component in providing relationship-based services via telehealth. Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.https://infantcrier.mi-aimh.org/therapeutic-presence-the-critical-component-in-providing-relationship-based-services-via-telehealth

Ferré, P., García, T., Fraga, I., Sánchez-Casas, R., & Molero, M. (2010). Memory for emotional words in bilinguals: Do words have the same emotional intensity in the first and in the second language? Cognition and Emotion, 24(5), 760–785.

Gilliam, W. S., Malik, A. M., Shafiq, M., Klotz, M. , Reyes, C., Humphries, J. E., Murray, T., Elharake, J. A., Wilkinson, D., & Omer, S. B. (2020). COVID-19 transmission in US child care programs. Pediatrics, 147(1), e2020031971. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/147/1/e2020031971/33500/COVID-19-Transmission-in-US-Child-Care-Programs

Hamre, B., Hatfield, B., Pianta, R., & Jamil, F. (2014). Evidence for general and domain-specific elements of teacher-child interactions: Associations with preschool children’s development. Child Development, 85(3), 1257–1274. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12184. https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdev.12184

Howes, C., & Sanders, K. (2006). Child care for young children. In B. Spodek & O. N. Saracho (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of young children (pp. 85–103). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525.

Jeon, L., Buettner, C. K., Grant, A. A., & Lang, S. N. (2019). Early childhood teachers’ stress and children’s social, emotional, and behavioral functioning. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 61, 21–32.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg01. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Knudson-Martin, C., McDowell, T., & Bermudez, J. M. (2019). From knowing to doing: Guidelines for socioculturally attuned family therapy. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 45, 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12299. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jmft.12299

Linnan, L., Arandia, G., Bateman, L. A., Vaughn, A., Smith, N., & Ward, D.(2017). The health and working conditions of women employed in child care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(3), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14030283. www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/14/3/283

McCormick, A., Eidson, F., & Harrison, M. E. (2020, January). Reflective consultation with groups via virtual technology: What is best practice? ZERO TO THREE. www.zerotothree.org/resource/reflective-consultation-with-groups-via-virtual-technology-what-is-best-practice

Nagasawa, M., & Tarrant, K. (2020). Who will care for the early care and education workforce? COVID-19 and the need to support early childhood educators’ emotional well-being. New York Early Childhood Professional Development Institute, CUNY. https://educate.bankstreet.edu/sc/1

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2020). Holding on until help comes: A survey reveals child care’s fight to survive. www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/our-work/public-policy-advocacy/holding_on_until_help_comes.survey_analysis_july_2020.pdf

Osofsky, J. D. (2020). PERSPECTIVES–Supporting young children, families, and caregivers related to the COVID-19 pandemic. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(Supp.) www.zerotothree.org/resource/perspectives-supporting-young-children-families-and-caregivers-related-to-the-covid-19-pandemic

Pianta, R., Steinberg, M., & Rollins, K. (1995). The first two years of school: Teacher-child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 7(2), 295–312. doi:10.1017/S0954579400006519. www.cambridge.org/core/journals/development-and-psychopathology/article/abs/first-two-years-of-schoolteacherchild-relationships-and-deflections-in-childrens-classroom-adjustment/6DF6FAFBC8F56E6ECDC726CFD9827603

Siegel, D. J., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside out. Penguin Publishing.

Stern, D. (1985). Affect attunement. In J. Call, E. Galenson, & R. Tyson (Eds.), Frontiers of infant psychiatry (33–44). Basic Books.

Tracey, S., Smith, L., & Jasinska, M. (2020). A glimpse into the child care industry: BPC interviews providers across the United States. Bipartisan Policy Center. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/blog/a-glimpse-into-the-child-care-industry-bpc-interviews-providers-across-the-united-states

Whitaker, R. C., Dearth-Wesley, T., & Gooze, R. A. (2015). Workplace stress and the quality of teacher–children relationships in Head Start. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 30, 57–69. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0885200614000891

Yoonjeon K., Montoya, E., Doocy, S., Austin, L. J. E., & Whitebook, M. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on the early care and education sector in California: Variations across program types. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 348–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.03.004. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0885200622000254?via%3Dihub