Kyong-Ah Kwon and Diane M. Horm, University of Oklahoma-Tulsa

Chris Amirault, Tulsa Educare MacArthur, Tulsa, Oklahoma

Abstract

Researchers from the Happy Teacher Project found that many early childhood teachers experience stress and demonstrate lack of well-being at rates and levels that threaten the quality and sustainability of the workforce. Further, working with children exposed to trauma adds significant emotional and physical burden on teachers who already struggle with poor well-being and poor working conditions, which can be considered “triple jeopardy.” Despite these prevalent risks, teachers often do not have adequate resources to support their well-being and work with children experiencing trauma. From a holistic and interdisciplinary approach, we offer recommendations at the individual, program, and system and policy levels.

Stella often got angry. Really, really, really angry.

Stella enrolled in our early childhood program after she transitioned to her second foster home–her first had declared her “too hard to handle.” She was in foster care due to the sustained neglect and sexual abuse she had suffered before she reached her first birthday. Now, as a 2½-year-old, her rages were potent and fierce, and many caregivers retreated when they devolved into kicking and biting.

But not her teacher Donna. While her colleagues retreated as Stella’s behavior escalated, Donna moved in; when others provoked battles by insisting on unachievable compliance, Donna connected by adjusting her expectations to meet Stella where she was at the moment.

One morning, Stella arrived at school with her hair more disheveled than usual, her eyes darting around the room as she entered, with the vigilant attention that Donna had learned to recognize as a key sign of Stella’s dysregulation. When Donna walked over to her to say hi, Stella rushed away to grab her favorite book, Brown Bear, Brown Bear. “Read,” she demanded. Donna said, “Sure,” sat down, and started the book, which they both knew by heart.

Stella sat quietly as Donna read the first few pages, imitating the sounds of the brown bear, red bird, and yellow duck before getting to the blue horse. But when she whinnied her best whinny, Stella turned and said, “NO!” “But horses whinny like that, Stella,” Donna responded.

“NO! That’s WRONG!” Stella insisted, growing more irate.

“Do they sound like this?” Donna asked, attempting another horse-like sound.

“NOOOOOO!!” screamed Stella, rising to put herself face-to-face with Donna, clenching her fists and shaking. “YOU’RE WRONG!”

Donna took a breath, looked into Stella’s eyes, and said in a quiet, calm voice, “It’s really hard when adults do things wrong, isn’t it?”

Stella instantly collapsed on Donna’s lap. “Yeah,” she sighed, and she melted into Donna’s arms.

Teachers’ experiences and mental health can serve to escalate or soothe young children’s trauma and stress. Photo: christinarosepix/shutterstock

Significance and Challenges of the Early Childhood Workforce

As illustrated in Stella’s story, early childhood teachers can play a large role in supporting children experiencing trauma and adversity. Young children thrive when they have secure, positive relationships with adults who know how to support their development and learning and who respond to their individual needs and characteristics (Institute of Medicine [IOM] & National Research Council [NRC], 2015). This is especially true for infants and toddlers given their unique developmental characteristics and dependence on adults (Horm et al., 2016).

A key conclusion of Teacher Interactions With Infants and Toddlers (a Research in Review article from the National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC]; Norris & Horm, 2015) was that sensitive–responsive interactions between teachers and the young children they support were linked to positive child outcomes in social skills, receptive language, expressive language, early literacy capabilities, and school readiness. The current research demonstrates that, through their interactions with young children, teachers can also buffer the negative impact of the adversity children may experience at home. Indeed, a growing body of research indicates that high-quality infant–toddler care can have significant short- and long-term effects on children’s development (Vandell et al., 2010; Yazejian et al., 2017). Thus, the teachers providing care and education for young children carry great responsibility for the health, development, and learning of young children (IOM & NRC, 2015).

Despite this responsibility, early childhood teachers are not consistently acknowledged as members of a workforce with specialized knowledge or competencies worthy of professional compensation and respect, and they rarely receive the supports needed to uphold this great responsibility to young children, their families, and society at large (IOM & NRC, 2015). As described in this article, the necessary knowledge base, competencies, and personal capacities of the teacher, including health and mental health, are expansive. To date, society in the US has not demonstrated the collective commitment to adequately support teachers of young children, widening the gap between what is known from accumulated research and the realities experienced by teachers and the young children and families they serve (IOM & NRC, 2015; NAEYC, 2020).

Importance of Early Childhood Teacher Well-Being

The opening story about Stella highlights how teachers’ experiences and mental health can serve to escalate or soothe young children’s trauma and stress. This is not merely a matter of caregiver skill and understanding. Recently, increasing attention has turned to early childhood teachers’ well-being as an important factor potentially impacting teachers’ beliefs in developmentally appropriate practices, their implementation of high-quality experiences for the young children in care, and children’s behavioral problems (H. Jeon et al., 2018; L. Jeon et al., 2014; Kwon et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2016).

For example, Kwon et al. (2019) found that the psychological distress (i.e., depressive symptoms) Early Head Start teachers experience was directly associated with their reports of children’s behavioral problems and the quality of emotional and behavioral support they provide to children. The researchers speculated that the direct association between teachers’ depressive symptoms and toddlers’ behavioral problems suggests that the children may react to and learn from teachers’ negative mood, behavioral modeling, and poor self-regulation resulting from their psychological stress. Also, teachers who feel depressed are less likely to provide positive emotional and behavioral support to children because the depressive symptoms may hinder their ability to serve as positive emotional and behavioral models, limiting their ability to provide warm and nurturing care.

Most noteworthy, teachers’ depressive symptoms were the only significant predictor of classroom emotional and behavioral support. It is commonly believed that other teacher characteristics such as teachers’ education, specialized degree, and teaching experience are the most important for classroom quality. This research challenges these beliefs.

Whole Teacher Well-Being: Need for a Holistic and Interdisciplinary Approach

Early childhood teachers care deeply about children. Thirty infant–toddler teachers interviewed for a study of turnover and retention almost unanimously said so (Kwon, Malek, et al., 2020). Similarly, most reported that, while they knew that early childhood education was not a well-paying or respected job, they chose it and wanted to stay in the profession because their work was meaningful and rewarding to them. Similarly, in another study with 262 early childhood teachers, most reported that they believed working with children was their calling and expressed high commitment to their work (Kwon, Ford, Salvatore, et al., 2020).

Even with personal satisfaction and high levels of commitment, teaching young children is a challenging profession. In fact, studies have raised concerns that many early childhood teachers struggle with poor physical and psychological well-being (Linnan et al., 2017; Otten et al., 2019; Whitaker et al., 2013). These problems add to and complicate the issues experienced by those in the early childhood workforce who, despite high job expectations, experience low pay and lack of systemic workforce appreciation. The infant–toddler workforce may be more affected given that they have even lower wages and status than the teaching workforce for older children (La Paro et al., 2014; Maxwell et al., 2009; Murphey et al., 2013; National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team, 2013). However, previous studies on teachers’ well-being have rarely addressed the particular workforce and well-being issues faced by infant–toddler teachers. The majority of studies on teacher well-being are also limited by considering a narrow scope of well-being, primarily focusing on teachers’ depressive symptoms or stress.

Well-being is multidimensional, yet physical health is an often-neglected dimension of teacher well-being. Few studies address, comprehensively, the aspect of working conditions that promote or exacerbate teachers’ physical and psychological well-being. In response to this gap in the literature, Kwon et al. (2019) launched a transdisciplinary initiative—the Happy Teacher Project—to investigate teacher well-being, incorporating perspectives and research techniques from multiple disciplines. This project team consists of researchers in early childhood education, interior design, physical therapy, public health, nutrition, and educational policy whose cross-disciplinary expertise creates a holistic approach to teacher well-being that considers not only the physical, psychological, and professional aspects, but also their interaction with various working conditions.

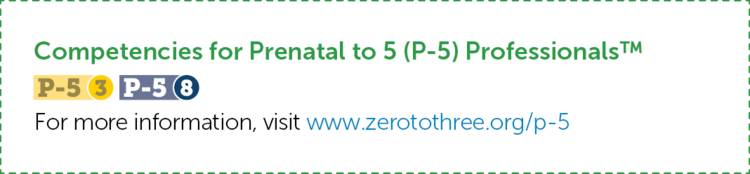

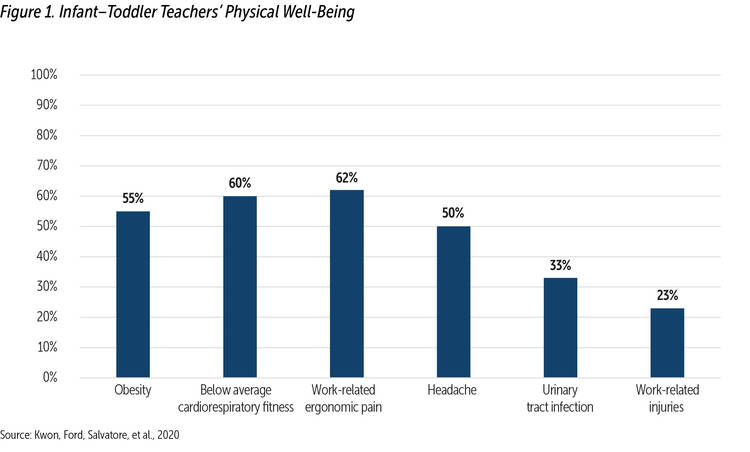

Findings of the Happy Teacher Project indicated that many early childhood teachers face serious issues with both their psychological and physical well-being (Kwon, Ford, Salvatore, et al., 2020), and experience significantly more physical health challenges than the general population (see Figure 1). From the analysis with a focus on infant–toddler teachers, about one third of the 158 infant–toddler teachers reported that they frequently felt stressed while on the job; 19% felt depressed. Sixty-two percent of teachers had at least one area of work-related ergonomic pain, 55% of the participating teachers were obese, 60% had below average cardiorespiratory fitness, and one third reported doctor-diagnosed urinary tract infection.

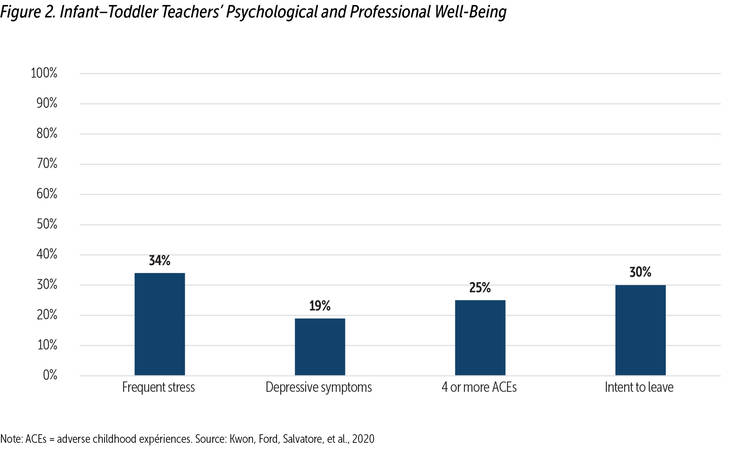

The Happy Teacher Project data showed that infant–toddler teachers experience significantly more physical job demands than preschool teachers. This finding may not surprise those familiar with the daily routine activities and physical tasks that infant–toddler teachers perform, such as lifting and carrying children, regular stooping and twisting, and sitting on ill-fitting, child-sized chairs. In fact, the Happy Teacher Project team found that 44% of infant–toddler teachers felt ergonomic pain while transferring a child (see Figure 2). Forty percent experienced ergonomic pain during diaper changing, which may be caused by having to lift children to and take them down from a diaper changing table, and bend over to help children wash their hands in a small sink countless times daily (see Figure 3). Early childhood teachers’ physical job demands clearly contribute to teachers’ physical well-being, including ergonomic pains and general health risks (Kwon et al., in press).

Despite these high physical and mental demands, infant– toddler teachers get little support for their work. Thirty-six percent of infant–toddler teachers reported that they do not have any designated daily break, and 34% do not even have a space for relaxation (Kwon, Ford, Salvatore, et al., 2020). Among the 40 teachers the team interviewed, 18 teachers mentioned the need for mental and physical breaks (c.f., only 3 teachers mentioned the need for professional development, coaching, and mentoring for improving their well-being). As one toddler teacher put it, “Daily break is the biggest frustration for me. A lot of teachers tend to build up their frustration inside.” Another teacher mentioned, “Because we do not have a designated break and cannot go to the bathroom, I always have to hold. We cannot get out of (teacher–child) ratio and often have staff shortage to cover me even for the bathroom break. So, I don’t drink water and often feel dehydrated.”

Teachers who feel depressed are less likely to provide positive emotional and behavioral support to children because the depressive symptoms may hinder their ability to serve as positive emotional and behavioral models, limiting their ability to provide warm and nurturing care. Photo: all_about_people/shutterstock

The physical and emotional toll is even more severe among teachers who serve children from low-income families, such as Early Head Start (EHS) and Head Start (HS). The Happy Teacher Project (Kwon, 2020) found that EHS/HS teachers tended to experience more job demands and stress, depressive symptoms, headaches, work-related injuries, and conflict with children than non-EHS/HS teachers (e.g., other center- or home-based programs, or pre-K programs). These data suggest that the ample mental health and physical health issues of EHS/ HS teachers may result, in part, from working with children from challenging home environments—a concerning suggestion given that they are expected to provide a safe and positive environment for children and to serve as a buffer for children who are experiencing poverty and its associated challenges.

Triple Jeopardy: Added Challenges of Working With Children With Trauma

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020), more than half of all U.S. children have experienced some kind of trauma. Researchers have extensively studied 10 types of early childhood traumatic experiences to calculate Adverse Childhood Experiences scores (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998). The 10 types include five personal (e.g., physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect) and five family-related (e.g., incarcerated family member, domestic violence, parental divorce) items, and researchers have examined how early adversity impacts health and well-being outcomes. According to the National Survey of Children’s Health (Maternal and Child Health Bureau, 2020), in 2017–2018, 1 in 3 children from birth to 17 years old had experienced at least one ACE in the US, and 14.1% had two or more ACEs. The extensive literature documents the impact of ACEs on a range of child and adult outcomes spanning mental health, substance use, and general medical conditions (Felitti et al., 1998; Nurius et al., 2012; Wing et al., 2015; Zarse et al., 2019). In addition to these identified ACEs, many other types of traumatic experiences can impact young children, including homelessness, poverty, bullying, racial discrimination, and negative experiences as a refugee or immigrant.

Well-being is multidimensional, yet physical health is an often-neglected dimension of teacher well-being. Photo: SVRSLYIMAGE/shutterstock

Given the prevalence of young children who experience trauma, it is likely that early childhood teachers have children exposed to trauma in their classrooms. In particular, infants and toddlers are the easiest targets for maltreatment, and it is reported that about 50% of the victims of maltreatment are children 3 years and younger (Children’s Bureau, 2020). This report also documented that more alleged reports of child abuse and neglect were filed by education personnel (20.5%) than by any other professional (e.g., legal and law enforcement personnel, social services personnel) and non-professional (e.g., neighbors, relatives) groups. This suggests not only the high likelihood of infant–toddler teachers’ working with children experiencing trauma but also the important role these teachers play.

Working with children who have a history of trauma adds significant emotional and physical burden on teachers who already struggle with poor well-being and poor working conditions, which can be considered “triple jeopardy.” Their well-being is likely to be compromised and their psychological distress amplified as a result of working with children exposed to trauma. In addition, a number of early childhood teachers have a history of trauma themselves. For example, the Happy Teacher Project found that about half of EHS and HS teachers reported two or more ACEs. Almost one quarter of EHS and HS teachers reported four or more ACEs (Kwon, 2020) which is higher than the general public in the US (i.e., 17%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). For these teachers, working with children experiencing trauma may trigger their own overwhelming adverse experiences.

Given the prevalence of young children who experience trauma, it is likely that early childhood teachers have children exposed to trauma in their classrooms. Photo: TierneyMJ/shutterstock

Even if they have not endured trauma or any mental health issues themselves, teachers exposed to children’s trauma may experience symptoms similar to those of the children in their care, referred to as secondary traumatic stress (Jenkins & Baird, 2002). They may also feel overwhelmed by the suffering and pain of children in their classrooms and experience compassion fatigue (Ray et al., 2013). The high level of anxiety and intense negative emotion that children experiencing trauma bring to school can affect the teachers who work with them. Children with trauma who are withdrawn and depressed may show difficulty engaging in learning activities. Also, because children’s traumatic experiences often manifest as random acts of aggression, many teachers report being hit, bitten, and kicked by children, which add to the physical demands of their job. Past research has found that the challenges of working with trauma-affected children can lead to teacher burnout (Antoniou et al., 2013) and leaving the profession (Rojas-Flores et al., 2015).

Despite the prevalent risks and challenges, many early childhood teachers report that they have not been prepared and do not receive support to work with children experiencing trauma. According to an informal survey collected from about 150 early childhood teacher participants during a conference at the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa on the topic of working with children experiencing trauma, the majority of participants mentioned that, because they have a child or children who have experienced trauma, they want to learn how to support those children better. Similarly, 1,434 teachers who participated in a COVID-19 impact study (Kwon, Ford, Tsortsoros, & Randall, 2020) reported that among 23 categories of resources and support they need to improve their well-being (e.g., higher wages, benefits, more breaks, wellness program, more staff, job stability), the second most frequently mentioned item after higher wages was more support for dealing with children’s behavioral challenges. It is clear that early childhood teachers have high needs for support for working with children having behavioral problems and experiencing trauma, challenges that threaten their well-being and work.

Caring for Teachers: Self-Care Is Not Enough

The research summarized in the previous sections is cause for concern. Like most complex problems, solutions depend on multiple levels–supports at the individual, program, and policy and system levels.

Individual Level

At the individual level, it is important for teachers to learn to recognize the warning signs and symptoms of psychological and physical distress, including depressive symptoms, health-related issues, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.

- First and foremost, if they feel the symptom, teachers need to take a break and relax to restore energy and to re-engage in their work.

- Teachers need to plan for and engage in self-care. Self-care and relaxation techniques vary and include reading, crossword puzzles, watching movies, enjoying music, exercise, spirituality or religious activities, gardening, playing board games, traveling, and meditation. Physical and outdoor activities, such as hiking, walking, and yoga, are great ways to restore energy.

- Teachers should express their concerns and actively seek resources to improve their well-being and the quality of their work with children, turning to peers and supervisors for support.

Program Level

At the program level, research indicates various features make individual workplaces more or less attractive and supportive.Programs can do the following to enhance staff well-being and support program quality:

- Create a positive work climate, with dedicated supervisory attention to core components such as reflective supervision, teacher appreciation, support for professional growth, and “soft skill” training on team collaboration, conflict resolution, and communication.

- Plan and provide more and regular breaks, not just daily, but also throughout the year, with adequate additional coverage to address unexpected staffing needs. Also provide a clean and comfortable space or a teacher lounge for relaxation.

- Provide support for holistic mental and physical health practices, such as employee assistance programs, self-care and mindfulness training, and memberships to gyms and other physical health programs.

- Design and implement on-going coaching and professional development founded on adult learning principles that addresses trauma-sensitive care, challenging behavior, and collaboration with families for a strength-based partnership.

Policy and System Levels

Though services for children birth to 5 years old are provided within a fragmented system (IOM & NRC, 2015), the research summarized in this article indicates the need for systemic changes and policy supports. Aligned with this goal, a recent initiative provides hope. NAEYC, in partnership with 15 other national organizations representing members of the early childhood field including ZERO TO THREE, have formed the national Power to the Profession Task Force and developed a consensus framework articulating competencies, qualifications, standards, compensation, and infrastructure needed to create and support a diverse and unified early childhood education professional workforce serving children birth through 8 years old across states and settings (NAEYC, 2020). This is an important initiative with the goal to transform the workforce and profession and, in turn, enhance the quality of services available for all young children (NAEYC, 2020). This work represents important steps in increasing the status, respect, and compensation of the early childhood education field.

Change is needed because the research summarized previously highlights:

- Appropriate salary and benefits are necessary but not sufficient—teachers and programs need more resources and support to fulfill their responsibilities to children, families, and society.

- While specialized trainings on working with children experiencing trauma can be helpful, new conceptualizations of professional development that include efforts to enhance professional knowledge and competencies in concert with supports to address and normalize mental health needs and services for the provider/teacher are desperately needed.

- Creative policy levers to support teacher well-being are needed in state systems to produce change; an example is adding indicators of teacher well-being to state early childhood education licensing and Quality Rating and Improvement Systems.

Children with trauma who are withdrawn and depressed may show difficulty engaging in learning activities. Photo: vladm/shutterstock

Concluding Thoughts

Finally, the story of Stella and Donna is a reminder of the intimate human moments these systems should support. While the Power to the Profession initiative and recommendations discussed in this article provide a foundation for positive change, the magic of early childhood (or lack of it) happens in the daily interactions between one child and the few adults entrusted with his or her care, what Bronfenbrenner and Morris labeled as proximal processes (2006). Thus, it is essential to ensure that any initiatives, no matter how promising at the individual, program, or national level, reach individual young children and their caregivers. As summarized in previous sections, teachers in early childhood settings experience stress and demonstrate lack of well-being at rates and levels that threaten the quality of teacher–child interactions and the quality of early childhood settings. The poor teacher well-being and the suboptimal working conditions threaten the early childhood workforce and limits their potential to offer the high-quality care and education that research shows can transform young children and support families and our collective future.

Author Bios

Kyong-Ah Kwon, PhD, has extensive experience as a teacher of young children in Korea and the US. She received her doctorate in developmental studies from Purdue University and is currently working as an associate professor at the University of Oklahoma-Tulsa. Dr. Kwon has served as a principal investigator and leader of the Happy Teacher Project on early childhood teachers’ well-being. She has an established record of scholarly work about parenting, classroom quality, and teachers’ well-being and each of their impacts on children’s development. She has been published in prestigious journals, such as Journal of School Psychology, Teaching and Teacher Education, and Early Childhood Research Quarterly.

Diane M. Horm, PhD, is the George Kaiser Family Foundation Endowed Chair of Early Childhood Education and founding director of the Early Childhood Education Institute (ECEI) at the University of Oklahoma–Tulsa. Through the ECEI, Dr. Horm is currently leading several applied research initiatives including program evaluation research in collaboration with Tulsa’s Educare programs. She serves on the Steering Committee of the Network of Infant-Toddler Researchers, a consortium that brings together researchers interested in policy and practice issues relevant to programs serving families during pregnancy and the first 3 years of life. Dr. Horm completed a ZERO TO THREE Harris Mid-Career Fellowship during 2007–2009 to support her work related to infants, toddlers, and their families. The focus of her fellowship was building more infant–toddler content into higher education degree programs, including the one at OU-Tulsa where she and Dr. Kwon both currently work.

Chris Amirault, PhD, is the school director of Tulsa Educare MacArthur in Oklahoma, and for more than 3 decades has dedicated himself to high-quality education, teaching courses and facilitating workshops on early childhood education, conflict, assessment and instruction, ethics and professionalism, challenging behavior, family engagement, anti-bias education, and equity. Prior to his arrival in Tulsa, he lived in Mexico, working as a consultant focusing on organizational culture, change management, and Quality Rating and Improvement Systems design in Oregon, Rhode Island, and California. For 13 years prior to that, he served as executive director of the Brown/Fox Point Early Childhood Education Center affiliated with Brown University in Rhode Island. During that time, he also taught early childhood education and development courses for area colleges and universities and served as a mentor and coach for providers throughout the community.

Suggested Citation

Kwon, K.-A., Horm, D. M., & Amirault, C. (2021). Early childhood teachers’ well-being: What we know and why we should care. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(3), 35–44.

References

Antoniou, A., Ploumpi, A., & Ntalla, M. (2013). Occupational stress and professional burnout in teachers of primary and secondary education: The role of coping strategies. Psychology, 4(3A), 349–355. link

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). Wiley.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Preventing adverse childhood experiences. Retrieved from link

Children’s Bureau, (2020). Child maltreatment 2018. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families. link

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. link

Horm, D., Norris, D., Perry, D., Chazan-Cohen, R., & Halle, T. (2016). Developmental foundations of school readiness for infants and toddlers, a research to practice report, OPRE Report # 2016-07. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Institute of Medicine (IOM) & National Research Council (NRC). (2015). Transforming the workforce for children birth through age 8: A unifying foundation. The National Academies Press. link

Jenkins, S. R., & Baird, S. (2002). Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious trauma: A validational study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(5), 423–432. link

Jeon, H.-J., Kwon, K.-A., Walsh, B. A., Burnham, M. M., & Choi, Y.-J. (2018). Relations of early childhood education teachers’ depressive symptoms, job-related stress, and professional motivation to beliefs about children and teaching practices, Early Education and Development, 30(1), 131–144. link

Jeon, L., Buettner, C. K., & Snyder, A. R. (2014). Pathways from teacher depression and child-care quality to child behavioral problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82, 225–235. link

Kwon, K.-A. (2020, November). Understanding and supporting early child teacher well-being and working conditions, Open plenary panel on trauma-informed practices at National Research Conference on Early Childhood (Virtual).

Kwon, K.-A., Ford, T. G., Jeon, L., Malek, A., Randall, K., Ellis, N., Kile, M., & Salvatore, A. (in press). Testing a holistic conceptual framework for early childhood teacher well-being. Journal of School Psychology

Kwon, K.-A., Ford, T. G., Salvatore, A., Randall, K., Jeon, L., Malek-Lasater, A., Ellis, N., Kile, M., Horm, D., Kim, S. G., & Han, M. (2020). Neglected elements of a high-quality early childhood workforce: Whole teacher well-being and working conditions. Early Childhood Education Journal. link

Kwon, K.-A., Ford, T. G., Tsortsoros, J., & Randall, K. (2020). Challenges and needs for work and well-being of early childhood teachers by teaching modality during the COVID-19 pandemic [Manuscript submitted for publication]. The University of Oklahoma-Tulsa.

Kwon, K.-A, Jeon, S. Jeon, L., & Castle, S. (2019). The role of teachers’ depressive symptoms in classroom quality and children’s developmental outcomes in Early Head Start programs, Learning and Individual Differences, 74, 101748. link

Kwon, K.-A., Malek, A., Horm, D., & Castle, S. (2020). Turnover and retention of infant-toddler teachers: Reasons, consequences, and implications for practice and policy. Children and Youth Services Review, 115061. link

La Paro, K. M., Williamson, A. C., & Harfield, B. (2014). Assessing quality in toddler classrooms using the CLASS-Toddler and the ITERS-R. Early Education and Development, 25, 875–893. link

Linnan, L., Arandia, G., Bateman, L. A., Vaughn, A., Smith, N., & Ward, D. (2017). The health and working conditions of women employed in child care. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 283. link

Maternal and Child Health Bureau. (2020). National Survey of Children’s Health data brief. Human Resources and Services Administration. link

Maxwell, K. L., Early, D. M., Bryant, D., Kraus, S., Hume, K., & Crawford, G. (2009). Georgia study of early care and education: Child care center findings. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, FPG Child Development Institute.

Murphey, D., Cooper, M., & Forry, N. (2013). The youngest Americans: A statistical portrait of infants and toddlers in the United States. Child Trends.

National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC). (2020). Power to the Profession and the unifying framework for the early childhood education profession. Young Children, 75(1). link

National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2013). Number and characteristics of early care and education (ECE) teachers and caregivers: Initial findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). OPRE Report #2013-38. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Norris, D. J., & Horm, D. M. (2015). Research in review: Teacher interactions with infants and toddlers. Young Children, 70(5), 84–91.

Nurius, P. S., Logan-Greene, P., & Green, S. (2012). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) within a social disadvantage framework: Distinguishing unique, cumulative, and moderated contributions to adult mental health. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 40(4), 278–290. link

Otten, J. J., Bradford, V. A., Stover, B., Hill, H. D., Osborne, C., Getts, K., & Seixas, N. (2019). The culture of health in early care and education: Worker wages, health, and job characteristics. Health Affairs, 38(5), 709–720. link

Ray, S. L., Wong, C., White, D., & Heaslip, K. (2013). Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, work life conditions, and burnout among frontline mental health care professionals. Traumatology, 19(4), 255–267. link

Roberts, A., LoCasale-Crouch, J., Hamre, B., & DeCoster, J. (2016). Exploring teachers’ depressive symptoms, interaction quality, and children’s socialemotional development in Head Start. Early Education and Development, 27(5), 642–654. link

Rojas-Flores, L., Herrera, S., Currier, J. M., Foster, J. D., Putman, K. M., Roland, A., & Foy, D. W. (2015). Exposure to violence, posttraumatic stress, and burnout among teachers in El Salvador: Testing a mediational model. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4(2), 98–110. link

Vandell, D. L., Belsky, J., Burchinal, M., Steinberg, L., Vandergrift, N., & NICHD ECCRN. (2010). Do effects of early child care extend to age 15 years? Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Child Development, 81, 737–756.

Whitaker, R. C., Becker, B. D., Herman, A. N., & Gooze, R. A. (2013). The physical and mental health of Head Start staff: The Pennsylvania Head Start Staff Wellness Survey, 2012. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10. link

Wing, R., Gjelsvik, A., Nocera, M., & McQuaid, E. L. (2015). Association between adverse childhood experiences in the home and pediatric asthma. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, 114(5), 379–384. link

Yazejian, N., Bryant, D., Hans, S., Horm, D., St. Clair, L., File, N., & Burchinal, M. (2017). Child and parenting outcomes after 1 year of Educare. Child Development, 88(5), 1671–1688. link

Zarse, E. M., Neff, M. R., Yoder, R., Hulvershorn, L., Chambers, J. E., & Chambers, R. A. (2019) The adverse childhood experiences questionnaire: Two decades of research on childhood trauma as a primary cause of adult mental illness, addiction, and medical diseases. Cogent Medicine, 6(1). link