Jennifer Zubler, Good Samaritan Health Center, Atlanta, Georgia

Susan J. Kressly, Kressly Pediatrics, Warrington, Pennsylvania

Sara del Campo de Gonzalez, Children’s Hospital of San Antonio Baylor College of Medicine, San Antonio, Texas

Abstract

Early identification of developmental delays and disabilities (DDs) is a key component of well-child visits. Recommendations for assessing children’s development during these visits continue to evolve. For almost a century, developmental milestones have been used to identify children with atypical development. More recently, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has supported the medical home model and clinical guidelines to improve early identification of DDs in pediatric primary care. AAP’s guidelines include a multilayered, continuous, collaborative, and family-centered approach to early identification. However, continued research, collaboration, and innovation across systems of care is needed to improve early identification of DDs.

Early childhood development provides the foundation for well- being and is a priority across multiple systems of care. Research continues to underscore the importance of strengths-based approaches to the early identification of difficulties including developmental delays and disabilities (DDs), and coordination of services in collaboration with families. Approaches include early intervention services, trauma-informed care, Safe Stable Nurturing Relationships to build resilience, developmental promotion, and strengthening of families.

Identifying DDs

DDs are common; up to 1 in 6 children has a developmental disability (Cogswell et al., 2022). Some DDs can be identified early on, others may take longer to identify. Prenatal testing and newborn screenings (e.g., hearing tests) can identify infants at risk for DDs. Comprehensive family histories and knowledge of environmental risk factors can assist care teams with additional tools, resources, and support prior to identification of DDs. Knowing an infant is at risk for DDs can help families prepare for additional care and support some children may need.

Children at risk for other types of DDs such as speech delays, learning differences, autism, attention deficit disorder, and more may be more difficult to identify during early childhood because there usually are no associated laboratory tests or visible signs that a child is at risk for or has these types of DDs.

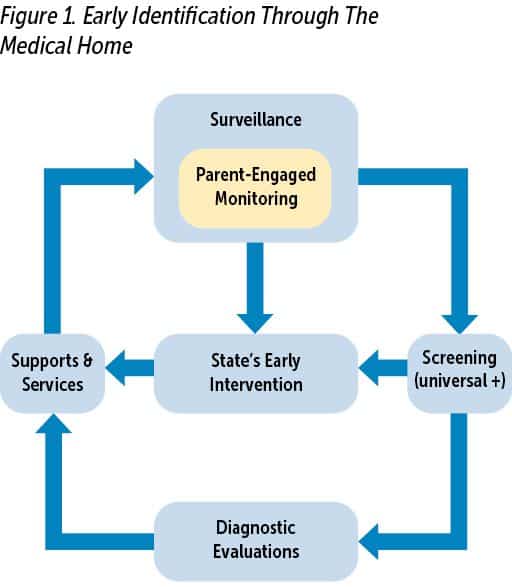

Whether identified before birth, during infancy, or during early childhood, early identification of DDs can allow children access to interventions when the brain is undergoing its most rapid development and interventions are likely to have the most benefit. Early childhood professionals (ECPs), including pediatric health care providers (HCPs), recognize the importance of early identification and work across systems to identify children and link families to supports and services (see Figure 1).

The Medical Home

While primary care has promoted the philosophy of the medical home, the term is often not well understood by families and others supporting the health and wellness of a patient. The medical home is not a building—it is a model of care that is patient-centered, comprehensive, team-based, coordinated, accessible, and focuses on quality (Primary Care Collaborative n.d.). For children, the model puts the child and family at the center and promotes the use of culturally effective interactions in order to best support them. All those who care for and support the child are valued members of the care team, including families, caregivers, early childhood educators, and more. Throughout this article, “family” will represent parents and/or other primary caregivers. The team extends not only to specialty medical services, but to all who contribute to the health and well-being of the child, and includes the medical home neighborhood (e.g., schools, early learning entities, community services).

Early Identification in the Medical Home

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends developmental surveillance at each well-child (health supervision) visit and developmental screening at certain well-child visits (Lipkin et al., 2020). Surveillance and screening can identify children who were not identified during pregnancy or infancy as having a risk for DDs and may not have obvious signs of DDs.

Well-visits involve much more than measuring a child’s physical growth and administering immunizations. Families are asked many questions, usually in the form of surveys or screening tools. In early childhood, the questions families are asked include questions about their child’s development including how they play, learn, act, speak, and move. Those questions are part of both developmental surveillance and screening.

The processes for developmental surveillance and screening have many similarities. Together they provide a continuous and layered approach to early identification of DDs through well-child visits in the medical home. The combination of surveillance and screening can improve early identification of DDs (Barger et al., 2018).

Developmental Surveillance

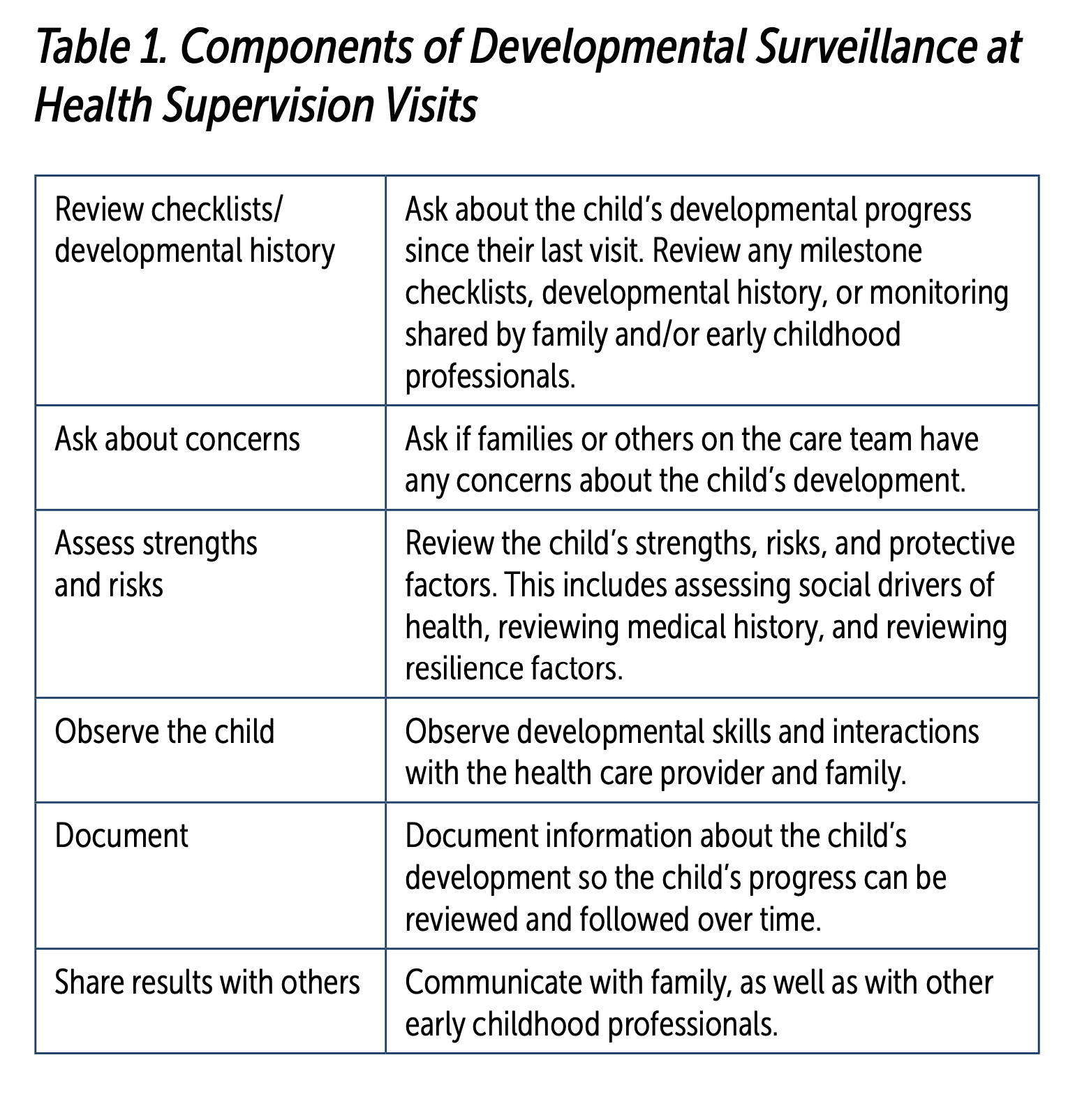

Developmental surveillance, recommended at each well-child visit, has several components (see Table 1). These include asking about the child’s developmental progress since their last visit; reviewing the child’s strengths, risks, and protective factors; asking if families or others on the care team have any concerns about the child’s development; observing developmental skills and interactions with the HCP and family; and documenting information about the child’s development so the child’s progress can be reviewed and followed over time.

Families may be better prepared for developmental surveillance during well-child visits if they are monitoring their child’s development between visits using resources like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” milestone checklists, including the Milestone Tracker app (Gadomski et al., 2018; Graybill et al., 2016). HCPs may also use CDC’s milestone checklists and/or other resources (e.g., Bright Futures) with families to ask what new milestones a child has reached and if families have any concerns about their child’s development. The use of milestone checklists is referred to as family-engaged developmental monitoring. This developmental monitoring by families and ECPs contributes essential information. However, it is only part of a more comprehensive process of developmental surveillance done at well-child visits.

Taking a strengths-based approach, HCPs review questions such as “What are some things you and your child do together?” or “What are some things your child likes to do?” which are also included in the CDC milestone checklists. These types of questions allow families to share strengths and protective factors in addition to providing developmental information that milestones alone may not capture. For instance, if a family shares they enjoy looking at books together, the HCP can congratulate the family on promoting their child’s early language learning and reinforce how talking, reading, and singing with children help children learn to communicate and later read.

Some children have a greater risk for DDs. Medical conditions like congenital heart disease or prematurity; family members with a history of DDs; and social drivers of health like poverty, poor nutrition, having a caregiver with mental health or substance use disorders, or other causes of toxic stress can put a child at risk for DDs. The well-visit and developmental surveillance also include reviewing the medical history, identifying social drivers of health, and supporting family resiliency by linking families to additional resources that ultimately can support a child’s developmental progress.

When HCPs play and interact with a child during visits, they are making observations about development, behavior, and engagement. HCPs see how children react to them entering the room. Does the child look to a parent for reassurance, do they hide their face behind their parent, or do they look inquisitively to see what the HCP will do? Does the child point at things in the room to show their parents something they want or something interesting? Do they make any noises or say any words to the HCP or the parent? Do they relax, smile, or play simple games like peek-a-boo? Do they have any comfort items, toys, or books with them? These and many other observations happen as the HCP talks with the family and performs an examination.

During the examination, HCPs will listen to a child’s heart and lungs, feel their abdomen, and look in their ears and mouth. However, they also take note of physical characteristics that may put the child at risk of DDs (e.g., vision or hearing difficulties, features of genetic syndromes). They also intentionally perform specific interactions during the exam to assess a child’s development. For instance, if they did not observe the child already reaching for objects, they may hold out a tongue depressor for the child to reach for or they may see if a child can sit on the examination table independently and then get on their hands and knees (“all fours”). The HCP will also assess a child’s muscle tone. They will see if the child will “talk” back and forth with them through cooing, babbling, jibber jabber, word approximations, or words, depending on the child’s age.

During the well-child visit, the HCP also discusses what new milestones lie ahead to foster continued developmental growth and age-appropriate interactions. For example, for a 12-month-old child who is advanced in walking, the HCP might discuss getting a child’s chair and table to foster them getting themselves in and out of a seated position now that they are moving toward independent mobility. The same child may not be as advanced in verbal expression, and the HCP can suggest strategies for promoting language development such as narrating what family members are doing throughout the day, and supporting nonverbal cues by asking a child for confirmation of what they are communicating (“Do you want the ball? Can you say ball?” Here’s the ball!”)

Although HCPs assess development throughout the well-child visit, visits with young children are unpredictable, provide a relatively brief period of time in which to assess development, and are not consistently accessible to all children. In addition, children with DDs will often interact and behave similar to typically developing children most of the time, limiting the effectiveness of observations during well-child visits by HCPs (Gabrielsen et al., 2015). Families may not recognize developmental concerns or be able to express their concerns or those of ECPs. Collaboration with other professionals across systems of care can help ensure the development of all children is being celebrated, supported, and monitored so actions can be taken if concerns arise. Individuals on the care team should be empowered to express concerns so that more formal evaluations can be implemented where appropriate.

ECPs, similar to HCPs, develop trusting relationships with families, celebrate children’s progress, answer developmental questions, and discuss families’ concerns. ECPs can include developmental specialists who may be providing developmental therapies or other health care specialists. It also includes early childhood educators and home visitors who have the opportunity to spend additional time with children and observe them in natural settings with other children.

In 2020, the AAP added another component to developmental surveillance that encourages collaboration across systems. It is now recommended that HCPs share and obtain developmental findings with other ECPs involved in the care of the child.

Resources like the CDC’s milestone checklists are being used to help communicate a child’s progress and concerns across systems of care as part of developmental surveillance. However, innovative solutions for effective system-level communication are needed to support families and reduce the communication burden for families and understaffed and under-resourced ECPs and HCPs.

This comprehensive continuous process of developmental surveillance during well-child visits can lead to developmental screening and/or developmental referrals if concerns are identified by an HCP or shared by the family or ECPs.

Developmental Screening

In addition to developmental surveillance at each health supervision visit, the AAP recommends routine/universal developmental screening at specific ages. Additional developmental screening is recommended if concerns arise at other ages/times (see Box 1). Screening looks very similar to surveillance because it typically involves families answering questions about a child’s development and milestones they have achieved. However, screening tools, unlike surveillance questions, are validated, meaning they have been tested against diagnostic tools to see if they can adequately identify children at risk for DDs. Examples of some common screening tools used by ECPs and HCPs are Ages and Stages Questionnaire-3 and Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, revised with Follow-up Questions. Although validated, screening tools can not diagnose a child with DDs; they provide a risk categorization. Meaning, they can indicate if a child might be at risk for a DD and the need for further evaluation to determine if a DD is actually present. Developmental screening tools are not perfect; they can over- and underidentify a child’s risk for DDs. They have variable sensitivities and specificities, which further vary depending on the settings and populations in which they are used. Adding complexity to the process, children may not have any identified risk for DDs with screening at earlier ages but with time their development may enter into an at-risk range.

Box 1. Why Provide Developmental Screening?

The AAP recommends universal developmental screenings at 9, 18, and 30 months old and autism screening at 18 and 24 months. Between 9 months and 2.5 years old, all young children should receive at least five developmental screenings using validated tools with an acceptable sensitivity and specificity. Additional age-appropriate screenings should be performed at any age/time surveillance identifies a concern or anyone on the care team expresses concerns.

There has been some confusion regarding whether or not the CDC’s milestone checklists are developmental screening tools. They are not. They can support some components of developmental surveillance (eliciting developmental history and concerns) and remind the care team of the importance of universal screening at recommended ages and additional developmental screening if children are missing milestones or other times there are concerns.

Surveillance and screening can identify children who were not identified during pregnancy or infancy as having a risk for developmental delays and disabilities and may not have obvious signs of them.

However, the previous CDC milestone checklists contained milestones that many children would not be expected to achieve by a specific well-child visit age. Appropriately, many HCPs may have reassured families rather than performing additional developmental screening if a child had not yet achieved 50th percentile milestones because about half of children would not be expected to achieve it. The revised CDC milestone checklists can better support additional screening by allowing families and HCPs to focus on milestones most children would be expected to achieve, decreasing unnecessary worry for families, and allowing more time to discuss other developmental concerns, or those not captured by milestones.

Although this discussion has focused on developmental screening done by HCPs, developmental screening is also done by some ECPs through their respective systems of care and following their own professional recommendations and requirements. Sharing developmental screening results across systems can improve access to care and inform those on the care team about a child’s strengths and areas where they may need additional support.

When health care providers play and interact with a child during visits, they are making observations about development, behavior, and engagement.

Referral for Evaluations and Services

If a child’s developmental screening, whether it was universal or additional screening, indicates a child is at risk for DDs, then further evaluation is recommended. In fact, even if developmental screening did not indicate a risk, further evaluation is still recommended if a family, ECP, or HCP still has concerns. So, why not skip screening and refer all children with concerns? In some situations, HCPs may refer without screening if there are obvious concerns, and the family agrees to proceed. However, many families may not have concerns when they attend well-child visits. Completion and review of developmental screening tools can support discussions about a child’s strengths and areas where they might benefit from additional support. These discussions can help families understand the reasons for referrals and can support resiliency when navigating the complex referral processes. Other reasons to do developmental screening when concerns are expressed include the following:

- determining which referrals might be most appropriate;

- supporting further discussions regarding a missed milestone by determining a risk categorization from several milestones in the same developmental domain on a validated screening tool;

- screening results may be requested by early intervention services or to determine urgency of a referral or to expedite referral processes to developmental specialists; and

- screening results can help follow a child’s development over time to establish need for future referrals if a child does not currently qualify for services, new referrals for new concerns, or to support continued discussions if a family chooses to not pursue evaluations or services when initial concerns arise.

Developmental referrals for further evaluations of developmental concerns are typically more complex than other types of referrals made by HCPs. Often families must navigate their state’s early intervention system in addition to referrals to developmental specialists like developmental and behavioral pediatricians, neurologists, child psychologists, and therapists (speech and language, physical, and occupational). The child may also require hearing and vision evaluations along with laboratory tests, depending on the nature of the developmental concerns.

In theory, developmental concerns are identified through surveillance and screening, HCPs and ECPs initiate referrals, and children receive necessary evaluations and appropriate early intervention services at a time when intervention may be most effective. However, the processes to obtain evaluations, supports, and services can be overwhelming for families, especially if they originally were not concerned about their child’s development or if the family has additional social determinants/drivers impacting health (Sapiets et al., 2021). Typically, early identification and intervention involves multiple conversations with families. Additional staffing resources and time are needed to address questions and barriers families may face in the referral process. It is not unusual to have a family run into a barrier, not qualify for services, and/or feel dismissed on the evaluation pathway and subsequently choose to “wait and see” rather than continuing to pursue referrals.

Follow-up on Referrals

The medical home model promotes dedicating practice resources to closing the loop on care. Doing this starts with understanding whether appropriate surveillance and screenings are happening in the context of well-child visits. This process can also be supported outside the medical home itself by promoting the importance of well-child visits.

For those children who were referred for additional evaluations, it is important to have a system to track and identify whether those evaluations occurred, obtain results, and review recommendations for services, supplemental services, and implementation of services. The AAP and the CDC have supported quality improvement projects for HCPs to learn and disseminate practical methods for closing the loop and improving surveillance and screening for early identification and linkage to services.

If children qualify for early intervention services, are they adequate? Is there a waiting list due to workforce shortages? Is there a shared understanding of whether early intervention services are felt to be all that is needed or are there additional services that should be instituted? If wait lists are unacceptable, are there other resources including medical insurance-based services in the interim? Setting appropriate care team expectations for the overall plan of care can go a long way to reducing anxiety and ensuring children are appropriately connected to care.

Upon further evaluation, if a child is diagnosed with DDs, HCPs and the medical home provide ongoing coordination of care, treatment planning, and assessment for additional support and services. Anticipatory guidance continues, as it does for all children, helping families know what to expect and how to plan for expected transitions such as middle school, puberty, driving, post-secondary education, and adult health care services.

Communication Is Essential for Early Identification

Effective communication involves cultural sensitivity and awareness that families are the center of a child’s care team. In order to inform families about typical development and for them to complete developmental surveillance and screening, the tools need to be available in different languages and written at a reading level accessible to the majority of families. Interpreters, cultural liaisons, or staff to read screening tools to families may be needed along with other communication accommodations to support early identification processes in HCPs’ offices. A trusted relationship between families and HCPs creates a safe environment to ask questions and raise concerns in a nonjudgmental manner.

It is important for HCPs and other ECPs to be aware that some families may have difficulties communicating concerns in a way that is easily recognized by professionals (Sices et al., 2009). Families might be reluctant to share concerns that potentially impact the hopes and dreams they have for their child’s future. Some families don’t share concerns expressed by other care team members because of their own personal experiences or those of family members and close friends. Those experiences might include having their concerns dismissed, having negative interactions when referred for additional evaluations, or having other barriers (e.g., financial, time, cultural) to following up with recommended care.

Ongoing care in the context of the medical home often allows HCPs to ask the “question behind the question” and gain a holistic view of the child’s development in the context of their overall health and environment. For example, a family may report a child’s behavior problem such as biting peers or throwing things when frustrated. An astute HCP will ask the family whether they think that behavior is typical for a child of that age or if they have concerns that there might be other reasons for the behaviors. Depending on the age of the child, and the extent of the behavior, it may be typical, or it could be that the child is having difficulty being understood with both verbal and nonverbal communication. Having a relationship over time with the family can facilitate open communication and necessary referrals for additional services if warranted or may result in the HCPs asking more questions about other aspects of the child’s development. There may be additional stressors in the family environment or with caregivers that the HCP can address and connect the family to appropriate services. Regardless, the HCP can provide the family advice and resources on how best to approach unwanted behaviors while simultaneously assessing any underlying reasons for the behavior.

Individuals on the care team should be empowered to express concerns so that more formal evaluations can be implemented where appropriate.

Sharing written observations across systems may improve communication and support next steps like developmental screening if there are concerns. Using similar resources across systems can improve communication and provide consistent messages to families about typical development, developmental promotion, the importance of well-child visits, and where they can seek help if they have concerns. In addition, promoting the concept of a care team within a medical home can help to foster collaboration and communication among all stakeholders involved in supporting the child and family.

The Future and Opportunities for Improvement

The medical home model emphasizes using team-based care which places the patient and family at the center. Team-based care “endorses the partnership of children and families working together with one or more health care providers and other team members across multiple settings to identify, coordinate, and address shared goals that meet the needs of the whole child” (Katkin et al., 2017, p. 2)

In support of this model, ECPs have a fundamental role to play working in partnership with families and other care team members to promote child development and wellness. AAP’s Early Childhood Champions, CDC’s Act Early Ambassadors, Early Head Start Health Services Advisory Committees, and others are working to support and coordinate local efforts.

Ideally, every child has access to a medical home with high-quality, comprehensive, coordinated, and family-centered care provided by a multidisciplinary care team. Unfortunately, some families lack access to a medical home and routine well-child visits or have significant barriers to using the access they have. Multiple layers of support for early identification and intervention for DDs is crucial to equitable access. This includes any tools and resources used by care teams, public health, and other stakeholders for promotion of healthy child development. Some describe this as a “Swiss cheese” method of care; some children may be “missed” at each layer, but it is less likely that “all the holes line up” and a child who needs additional care and resources is not identified.

Effective communication involves cultural sensitivity and awareness that families are the center of a child’s care team.

New models of well-child care are evolving to expand services within the trusted medical home. Services being added include embedding social workers, case managers, and mental and behavioral health specialists in a coordinated centralized manner. Centralizing coordination of care adds value for families and uses less resources, connecting families to resources with less risk for fragmentation and missed opportunities. Care teams who understand family-centered care can coordinate services for appropriate housing, transportation, nutrition, education, child care, literacy, medical, dental, mental health, and supporting healthy development, significantly impacting child outcomes.

Opportunities to co-locate developmental specialists and support to navigate early intervention services can improve access in the medical home (e.g., Help Me Grow, Early Childhood Home Visiting Programs, and HealthySteps programs). These programs that provide assistance for families to complete referrals and address questions and concerns in a culturally sensitive and appropriate manner have the potential to add significant value for families.

However, current health care payment models do not support the pediatric medical home model. Payment for Medicaid is most often inadequate to provide comprehensive services and often significantly less than Medicare rates. Time spent coordinating care, collaborating with others, and supporting families is often not recognized and appropriately paid. Payers often have limitations on whether multiple services can be provided and paid for on the same day, requiring the family to schedule separate appointments. Current billing codes for care coordination and time/work spent between patient contacts, including communicating with ECPs, are not universally recognized nor valued appropriately by payers. Telehealth services which increase access have limitations on scope of payment and financial sustainability. Barriers to appropriate payment must be removed so children can be cared for in

a family-centered manner. In addition, credentialing and participating network constraints for embedded specialists currently hinder widespread adoption of integrated care delivery models.

One significant opportunity for improvement is creating standardized communications methods that work across systems without placing responsibility on the family to facilitate the communication. There are current interoperable communications within health care that have promise but have not been widely expanded to partners outside of health care settings. Current models for exchanging other important child health information include shared regional immunization and statewide newborn screening registries that provide multidisciplinary access. There is ample opportunity for innovative collaborative solutions to improve communications and ultimately impact care.

In the meantime, care teams will continue advocating for children and families. As ECPs and HCPs put the family at the center of care, they must work together to reduce barriers to effective communication, collaboration, and optimal care for every child.

Learn More

Developmental Concern? Next Steps for Families and Caregivers (Family-Friendly Development Referral Guide). American Academy of Pediatrics

LTSAE_FamilyFriendlyGuide_form updated 10-22.pdf

Developmental Surveillance and Screening (Video)

www.aap.org/en/patient-care/developmental-surveillance-and-screening-patient-care

Identifying Risks Strengths, and Protective Factors for Children and Families: A Resource for Clinicians Conducting Developmental Surveillance https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/LTSAE_PediatriciansResource Guide.pdf?_ga=2.157614777.2044642445.1654007845- 1122348881.1649905248

Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents (4th ed.) American Academy of Pediatrics

www.aap.org/en/practice-management/bright-futures/bright-futures-materials-and-tools/bright-futures-guidelines-and-pocket-guide

CDC’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” Milestone Checklists and Milestone Tracker App

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones/index.html

Vroom

www.vroom.org

Reach Out and Read

www.reachoutandread.org

Authors’ Note

Dr. Jennifer Zubler is not employed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; the findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Authors

Jennifer Zubler, MD, FAAP, is a volunteer pediatrician at The Good Samaritan Health Center and a pediatric consultant for Eagle Global Scientific. She participates in work to improve early identification of children with developmental delays and disabilities supporting collaborations with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” program. Dr. Zubler has helped develop training resources, messaging, quality improvement projects, and other resources for early identification by health care providers and families. She has more than 25 years of clinical experience working with children and families and currently volunteers as a general pediatrician and coordinates a developmental and behavioral multidisciplinary pediatric clinic where she assists families in navigating medical and educational systems of care. Dr. Zubler is actively involved in the AAP as a member of the Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics’ Executive Committee where she is co-chair of the advocacy committee and a member of the primary care committee, the Georgia AAP chapter as a member of the Council on Children With Disabilities, and Georgia State University’s Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental Disabilities program.

Susan J. Kressly, MD, FAAP, is the founding partner of Kressly Pediatrics in Warrington, PA. She is board certified in general pediatrics and clinical informatics and has more than 30 years of experience providing care to children and supporting families. Dr. Kressly holds several leadership roles in health information technology and pediatrics and currently serves as chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Payer Advocacy Advisory Committee. She has worked on several projects streamlining developmental surveillance and screening using technology tools and quality improvement methods to improve efficiency and coordination within practice workflows. In addition, Dr. Kressly has been involved with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” program and AAP cooperative agreement projects including co-authorship of an AAP PediaLink education course.

Sara del Campo de Gonzalez, MD, FAAP, is a general pediatrician at Baylor College of Medicine, Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Prior to her current role, she worked for Harvard Center on the Developing Child in providing expert consultation, connections, and thought partnership in support of the Center’s strategic planning. Prior to relocating to San Antonio in 2021, Dr. del Campo de Gonzalez was the medical director at the Young Children’s Health Center, a community- based behavioral health integrated pediatric medical home at the University of New Mexico. While there, Dr. del Campo de Gonzalez served as the director of the pediatric resident rotation in advocacy and community engagement, a role she has continued at the Baylor College of Medicine pediatric residency program of San Antonio. She has served in various roles with the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in the areas of early childhood wellness, developmental surveillance, screening, and referral systems, as well as social determinants of health screening in pediatrics. This work with the AAP has led to opportunities in Pedialink course development and faculty presentations in webinars/podcasts as well as contributing to collaborative projects between AAP and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” program.

Suggested Citation

Zubler, J., Kressly, S. J., & del Campo de Gonzalez, S. (2022). Ensuring every child's success: Early identification of developmental delays and disabilities through the medical home model. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 43(1), 18–26.

References

Barger, B., Rice, C., Wolf, R., & Roach, A. (2018). Better together: Developmental screening and monitoring best identify children who need early intervention. Disability and Health Journal, 11(3), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.01.002. www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1936657418300037

Cogswell, M. E., Coil, E., Tian, L. H., Tinker, S. C., Ryerson, A. B., Maenner, M. J., Rice, C. E., & Peacock, G. (2022). Health needs and use of services among children with developmental disabilities-United States, 2014–2018. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71(12), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7112a3. www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/71/wr/ mm7112a3.htm?s_cid=mm7112a3_w

Gabrielsen, T. P., Farley, M., Speer, L., Villalobos, M., Baker, C. N., & Miller, J. (2015). Identifying autism in a brief observation. Pediatrics, 135(2), e330–e338. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-1428. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/135/2/e330/33414/Identifying-Autism-in-a-Brief-Observation?redirectedFrom=fulltext

Gadomski, A. M., Riley, M. R., Scribani, M., & Tallman, N. (2018). Impact of “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” materials on parental engagement and doctor interaction regarding child development. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 39(9), 693–700. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0000000000000604. https://journals.lww.com/jrnldbp/Abstract/2018/12000/Impact_of__Learn_the_Signs__Act_Early___Materials.3.aspx

Graybill, E., Self-Brown, S., Lai, B., Vinoski, E., McGill, T., & Crimmins, D. (2016). Addressing disparities in parent education: Examining the effects of Learn the Signs/Act Early parent education materials on parent outcomes. Early Childhood Education Journal, 44(1), 31–38.

Katkin, J. P., Kressly, S. J., Edwards, A. R., Perrin, J. P., Kraft, C. A., Richerson, J. E., Tieder, J. S., Wall, L., and Task Force on Pediatric Practice. (2017). Guiding principles for team-based pediatric care. Pediatrics, 140(2), e20171489. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3449. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/140/2/e20171489/38651/Guiding-Principles-for-Team-Based-Pediatric-Care

Lipkin, P. H., Macias, M. M., & Council on Children With Disabilities, Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. (2020). Promoting optimal development: Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders through developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics, 145(1), e20193449. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-3449. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/145/1/e20193449/36971/Promoting-Optimal-Development-Identifying-Infants

Primary Care Collaborative (n.d.). Defining the medical home: A patient- centered philosophy that drives primary care excellence. www.pcpcc.org/about/medical-home

Sapiets, S. J., Totsika, V., & Hastings, R. P. (2021). Factors influencing access to early intervention for families of children with developmental disabilities: A narrative review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual disabilities: JARID, 34(3),695–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12852. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jar.12852

Sices, L., Egbert, L., & Mercer, M. B. (2009). Sugar-coaters and straight talkers: Communicating about developmental delays in primary care. Pediatrics, 124(4) e705–713. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0286. https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article-abstract/124/4/e705/71872/Sugar-coaters-and-Straight-Talkers-Communicating?redirectedFrom=fulltext