Growing Up Bilingual: Challenges and Comforts

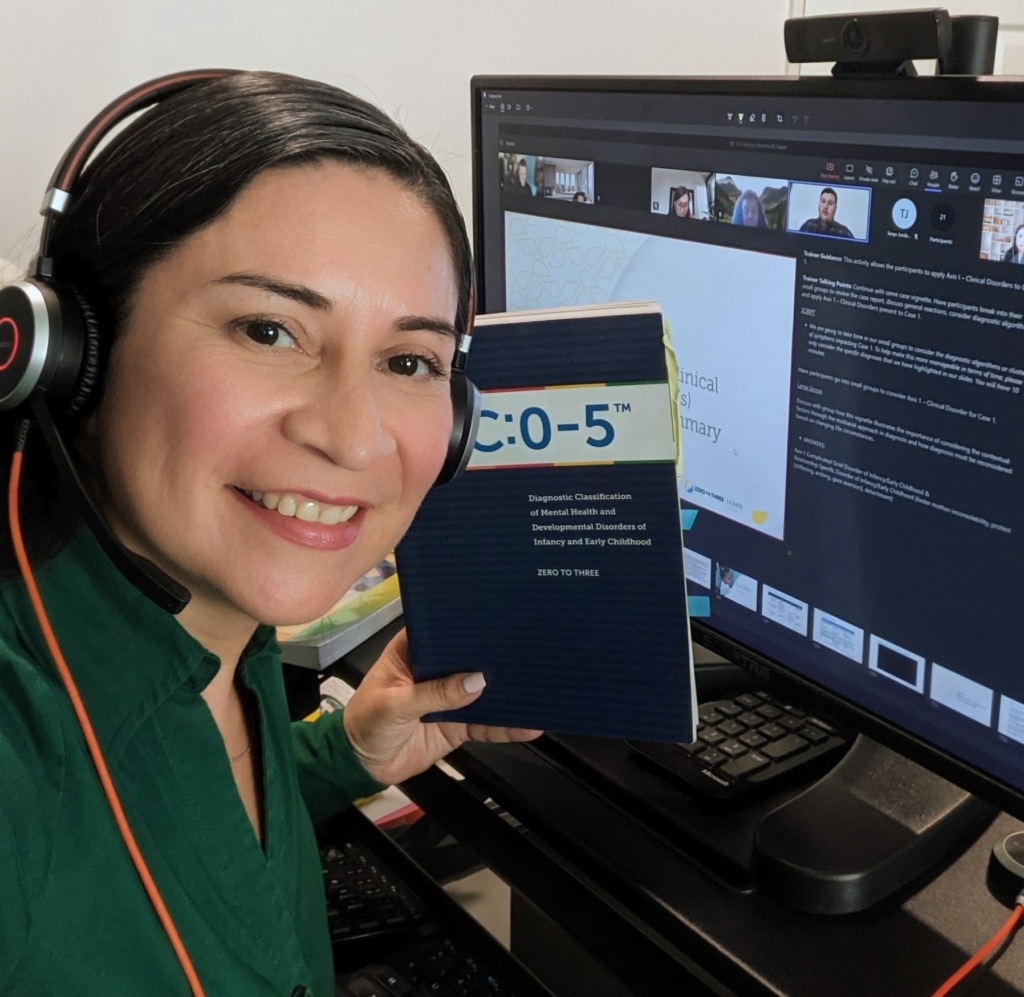

Verónica is a bilingual/bicultural licensed clinical psychologist and birth-to-five subject matter expert with Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health Prevention Services Division’s Family and Community Partnerships Unit. As a first-generation Mexican American, Verónica has first-hand experience with the unique challenges and systemic barriers facing BIPOC families seeking culturally informed and developmentally appropriate services. These experiences have shaped her passion for advocating for quality, relationship-based and trauma-informed services for young children and their families.

Lost in Translation

Although I was born in the United States, I spent my early childhood years growing up in a small, close-knit pueblo set against the mountains of Guanajuato, a central state in México.

My first language was Spanish; I didn’t begin learning English until my family returned to the United States, or el Norte as it commonly referred to, when I was seven years old. To this day I remember how frustrating it was not to be able to understand what others were saying, how lost I felt being unable to communicate with others, and vice versa. I still remember going to the doctor, dentist, and even the school office with my mom who also didn’t speak English, to meet with providers who did not speak Spanish.

Many important things were left unsaid or lost in translation because of the language barrier we so frequently encountered. Looking back, I think it was this frustration and discomfort with feeling lost that ultimately motivated me to really focus on learning the English language. Learning English was also a way that my siblings and I could you communicate if we didn’t want our parents to understand. But I also understood at that point the importance of maintaining my native tongue, because the Spanish language was a vital thread that connected me to my family and to my roots.

It's funny to think that learning English and mastering the language was necessary to survive in this country but maintaining my Spanish was also needed to survive in my community in which the vast majority of people spoke only Spanish.

Verónica Chávez

Finding Comfort

Growing up bilingual has always been meaningful but there were definitely instances when I was reminded just how meaningful and valuable it was that I was fluent in two languages and cultures.

Even though I learned to read in Spanish when I was young, I did not learn proper Spanish grammar until I was in high school. In my youth, my judgment of whether a form of speech was correct was based on my intuition as a native Spanish speaker, not whether it was grammatically correct. As a first-generation Mexican American and the first in my family to attend college, I remember how excited I was to leave California for Washington, D.C., to attend Georgetown University. And it was there, some 3,000 miles away from home, that I recall intentionally reflecting upon the importance of my ability to speak two languages for the first time.

My interactions with Spanish-speaking individuals at Georgetown, such as the drivers of the student shuttles that would transport me across campus and the staff of campus dining halls where I ate every day, caused me to long for home but paradoxically provided an incredible sense of comfort that I hadn’t realized I needed. During college and the two years post-college when I participated in a postbaccalaureate fellowship at the NIH to gain experience in preparation for graduate school, I didn’t read or communicate in Spanish very often.

When I started my doctoral program in Nebraska my Spanish was also underutilized until I had the incredible opportunity to work with a middle-aged monolingual Spanish-speaking couple seeking couples therapy. During my work with them, I came to realize the importance of being able to speak in your native tongue about one’s deepest fears and most treasured wishes. Language is so inextricably tied to our emotions and thoughts that it is often not possible to fully communicate vulnerable emotions and experiences in a language you are not fully comfortable communicating in.

She says, "Raising my sons in a bilingual and bicultural context not only continues to preserve my culture and the customs of my ancestors, it ensures that they may have the opportunity to support Spanish speakers and offer solace through the use of the language and continue to break down language barriers, regardless of the field of work or industry they enter when in the future. In my own work, having children of my own has increased my earnestness and passion for supporting and helping children and families thrive following adverse life experiences."

Bilingualism in a Therapeutic Setting

After completing my graduate training, I returned to California for my postdoctoral fellowship.

The diversity of Los Angeles County, where hundreds of different languages and dialects are spoken, allowed me to more frequently utilize and fully develop my Spanish language abilities within the context of a mental health setting. Being bilingual and able to speak the language is not the same as using Spanish in therapeutic settings, a fact I first confronted years earlier while working with the Spanish-speaking couple in Nebraska. There is so much clinical jargon that is difficult to translate into Spanish in the moment and so it was the beginning of a developing a different bilingual fluency.

While every client and family that I have worked with has meaning and is important, I can honestly say that I remember every single Spanish-speaking client and family I have worked with. And as I sit here and think why that would be, I think back to when my mom and I used to go to medical or dental appointments where no one spoke our language, and I know that I have been fortunate enough to give a Spanish-speaking family a different and hopefully more comforting experience than what I had growing up.

My work in infant and early childhood mental health has been richer because of my ability to speak Spanish with my Spanish-speaking families. Trauma work is hard, and it is that much harder when individuals are not able to process that trauma in their native language, in their language of comfort. Over the past decade I’ve worked with many families, some of them whom have extensive histories of trauma that has long gone unprocessed because the family couldn’t find a provider that spoke their language and understood their culture and customs.

Being able to provide services for Spanish-speaking people, to create a safe space and listen and speak their language and also journey with them through their trauma, is more than I could have asked for and a privilege.

Verónica Chávez

To address this issue, Verónica created and translated clinical documents and informational materials into Spanish and shared them widely. She sees this as another important step in providing quality bilingual services.

Breaking Down Barriers

Because of my early experiences of difficulty communicating with providers in a common language, I am very intentional about making sure that Spanish-speaking clients, potential clients, people I meet in the grocery store, people who are asking directions, and others know that I can speak with them in their native tongue.

Those early experiences also made me very aware of what I can do to ensure that people who come in to seek mental health services experience less barriers when doing so. Language barriers are significant in any context but become monumental within the context of mental health care because of the stigma associated with seeking treatment. It becomes even more complex when we start to think about culture and the meaning that different cultures may make of seeking help outside of their immediate family and their community.

Given the diversity of languages in Los Angeles County, most providers have available forms in multiple languages which is important. It’s vital that people have a full understanding of informed consent in a language that they can read or understand if their literacy is limited.

In my clinical practice as well as in my supervision and training of other clinicians, I have been intentional in emphasizing the importance of building awareness around implicit biases, engaging in on-going training and practice related to cultural humility and sensitivity, infusing cultural context in creating safe spaces for people to communicate in the language in which they feel most comfortable, and remaining culturally responsive in their interactions with clients. Most recently my work has focused more on reflective practice/supervision, training, and consultation with clinicians and as part of those activities I focus significantly on cultural context, the importance of being culturally informed.

There will always be cultural and linguistic nuances within languages, for instance, the Spanish spoken in Central México may differ from coastal regions of Mexico and certainly from other parts of Latin America. Consistent awareness of individual differences can help us remain attuned to each client’s individual needs. As a life-long curious learner I hope to continue to find ways to support our immigrant communities and break down cultural and linguistic barriers.

Browse our library of early development resources available in Spanish.