Karol Wilson, West Bloomfield, Michigan

Carla C. Barron, Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute, Wayne State University

Abstract

Reflective supervision is best practice within the infant and early childhood field. Reflective supervisors and supervisees work together to develop a shared space within which both can express their emotional response to work with very young children, caregivers, and families. Supporting professionals using reflective supervision requires a trusted, nurturing, and sensitive relationship that includes opportunities to reflect on racial and cultural differences, biases, values, and judgments. Holding in mind diversity, equity, and inclusion practices is critical within reflective supervision. This article explores four guiding principles of diversity-informed reflective supervision that when put into practice can support ongoing dialogue and embrace and honor diverse perspectives among professionals, caregivers, and families.

The introduction of the Tenets Initiative (Irving Harris Foundation, 2018) grounded the infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) field in aspects of diversity, equity, and inclusion and challenged the field to think about how biases, narratives, and histories can, if not explored, have a negative impact on the services offered to caregivers and families with young children. The Tenets brought to the forefront that who and how we are play a significant role in how we respond as infant and early childhood (IEC) professionals.

Relationship-based work involves partnering with caregivers and families to embrace the joys and challenges of caring for very young children. This partnership promotes the primary service goal of strengthening the caregiver–child relationship and supporting child well-being and development (Weatherston et al., 2020). The IEC professional extends an invitation to caregivers to engage in a relationship where they can consider together what supports or gets in the way of responding to their child’s behaviors and emotions. Optimally in this shared space, caregivers are offered a relational and emotional experience that parallels what they want to offer the child—responsivity, consistency, nurturance. For this to occur the caregiver must feel cared for and be an active participant in the creation of the relationship with the IEC professional. In this way, the relationship between the caregiver and professional is co-created, thus supporting opportunities for bravery, vulnerability, and an honest examination of emotions, thoughts, values, and beliefs (Wilson, 2021). Similarly, relationships within reflective supervision (RS) develop through exchanges between supervisees and supervisors that are impacted by what each brings to the supervisory experience, including their values, biases, and unique early experiences (Wilson et al., 2021).

Early Experiences Impact All Relationships

Thus, early relationship experiences can impact relationship development in IEC work, including RS. In the IEC field, professionals value the attachment relationship and think deeply about how to support the caregivers, families, and children that access such services. Along with those whom IEC professionals serve, one also needs to think about how early experiences and attachment impact all important relationships in this work, including the IEC professional’s experience. Through the attachment relationship, one’s internal working model of oneself and relationships is developed (Bowlby, 1969). Attachment patterns emerge based on bids and responses within the caregiving relationship. Over time and repetition, they inform the infant on what to expect in interaction with caregivers and their environment. An internal working model is a mental representation of the relationship with the primary caregiver that becomes a template for future relationships and allows individuals to predict, control, and manipulate their environment (Bowlby, 1969). Internal working models help people come to an understanding of themselves and others within a relationship. As individuals develop as IEC professionals, their internal working models can influence how they show up for those whom they work with and what to expect from them as partners in co-creating these therapeutic relationships.

It is important to note that scholars in the field acknowledge that empirical research on attachment needs inclusion of more Black families, additional intentional examination of the impact of anti-Black racism, and recognition of the empirical and theoretical literature of scholars of color (Stern et al., 2021). Further, it is important to reconsider early attachment research that highlighted diversity within early caregiving practice. For instance, Mary Ainsworth identified how varying cultural differences impact the caregiver and infant and inform what can be learned about their developing attachment relationship (Karen, 1994). When she traveled to Uganda to observe weaning practices between infants and caregivers, the expectation was that she would find abrupt interactions. Instead, Ainsworth observed babies who were weaned with sensitivity and observed attachment in the making (Ainsworth, 1967; Karen, 1994). Applying this to the parallel relationships that are part of IEC therapeutic work, we posit that differences in cultural, racial, and other social identities need to be considered and honored within all relationships.

The Parallel Relationship: Reflective Supervision

The supervisee and supervisor bring their relational experiences as they work to build an alliance with identified clients and with each other (O’Rourke, 2011; Weatherston & Tableman, 2015). RS offers opportunities to develop a contemplative space to think deeply about how what they bring impacts how they are within their work (Wilson et al., 2021). RS can offer consistency, predictability, and opportunities for reflection, and it evolves as the relationship matures (Schafer, 2007; Weatherston & Barron, 2009). This space of reflection can parallel the developing relationship and emotional responses between the supervisee and their identified clients (Pawl, 1994). Like IEC work with families, when safety and bravery are fostered in RS, the supervisee feels fueled to think more deeply about their therapeutic work and relationship between the caregiver and child (Fenichel, 1992).

Research with supervisees has found that understanding the RS process and valuing how it can impact their work were critical for the supervisee to use this experience within their therapeutic relationships (Barron et al., 2022). Through the process of RS and development of a trusting relationship with their supervisor, supervisees may be more willing to explore biases, bring up experiences of mis-attunement with clients, and identify differences that may interfere with their work (Stroud, 2010). When supervisees feel supported and heard by their supervisor, the supervisee can cultivate empathy and curiosity necessary to enter intentional and crucial conversations to better understand and honor the meaning behind behaviors—their own, the caregiver’s, and the child’s (Wilson et al., 2018).

The Skilled Dialogue Approach

A way to engage in relationships that holds in mind the uniqueness of everyone is the Skilled Dialogue approach (Barrera & Kramer, 2017). Skilled dialogue is a technique used to enhance communication by responding, acknowledging, and supporting diversity. Barrera and Kramer proposed that interpersonal interactions are skillfully designed to be respectful, reciprocal, and responsive. In the Skilled Dialogue approach, diversity and differences related to race and other social identities are seen as opportunities for growth, learning, and not something to change or control (Barrera & Kramer, 2017). Choosing relationship over control balances the power differential within all relationships by acknowledging the power of the other (Barrera & Kramer, 2017). This choice honors all that transpires in a relationship, including disruptions.

Disruptions are part of any relationship, and the quality of the repair is impacted by how willing those involved are in being vulnerable, authentic, and invested in maintaining and enhancing the relationship, noting that each perspective is meaningful and valuable (Barrera & Kramer, 2017; Wilson, 2021). Building on the Skilled Dialogue approach and the concept that relationships impact relationships at many levels, the following can be considered when supervisors and supervisees agree to building a co-created reflective space:

- Hold in mind that each individual’s internal working model of relationships contributes to the mental representation of how worthy, valuable, and successful they feel as participants within the RS relationship. Internal representations influence what participants expect from themselves and others within relationships (Bowlby, 1969). IEC work that supports parent–child relationships can be emotionally evocative. It can spark memories of loss, pain, trauma, and joy associated with early experiences (Jones Harden, 2010). Co-creating a reflective space to consider the examination of early experiences and what it means in IEC work with families can bring more clarity and opportunities.

- Co-create relationship agreements that will explore how narratives, past relationships, and identity influence responses. Relationship agreements acknowledge the possibility for disruptions. The supervisee and supervisor recognize there will be differing opinions, and challenges, but they agree to invest in the relationship and will work to understand each other’s experiences (Wilson et al., 2021).

- Understand that relationship-building in RS may take longer and require more vulnerability when race and racial differences are explored (Wilson et al., 2018). Building relationships is a process that involves feelings of safety, bravery, and vulnerability. A trusting relationship develops over time and is impacted by multiple variables (Barron et al., 2022).

Attachment patterns emerge based on bids and responses within the caregiving relationship. Photo: shutterstock/Ivana Lukiian

Considering Race and Diversity in RS Can Lead to a Stronger and More Diverse Workforce

Race, culture, and identity are integral to everyone (Thompson & Carter, 1997). They are essential parts of what makes people unique and complete. They are part of a foundation for being in and understanding relationships. The murder of George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, the Me-Too movement, and the global COVID-19 pandemic propelled many individuals into creating and engaging in dialogue that examines beliefs about race, culture, and identity in ways that had not been talked about with such bravery and purpose within the IEC field to date. George Floyd’s cries for his “mama” impacted mamas from all races and cultures. His words, “I can’t breathe” resonated with many whose loved ones were wheeled into hospitals, put on life support, and died from the COVID-19 virus. The pandemic forced IEC providers to find new ways to maintain connection with families and caregivers that upheld health and safety protocols (Marshall et al., 2020). Providers and their clients had to use phone or virtual meetings that made it harder to connect and increased feelings of helplessness (Marshall et al., 2020). Relationships were abruptly disrupted and many protective factors that families, caregivers, and providers depended on were removed. Populations that were already experiencing marginalization and oppression were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic (Fortuna et al., 2020).

Supervisees and supervisors may feel overwhelmed and burdened by system changes and the decrease of already strained community resources. IEC providers and the populations they work with have had to adjust to virtual meetings, feelings of isolation, loss of loved ones, as well as loss of finances and job stability. Many professionals and caregivers feel depleted and fraught with anxiety, making it difficult for parents to be as responsive to their infants and young children and challenging the professional’s capacity to be present (Ribaudo, 2021).

IEC services are crucial and necessary, especially during times of uncertainty and fear. In this field, relationships matter and are powerful tools to be used to create change (Weatherston et al., 2020). Thus, the impact of the pandemic, systemic racism, and social injustice must be challenged with more intensity and honesty by leaders and providers. An examination of how diversity can be seen as an opportunity for connection instead of a barrier to relationships needs to be regularly discussed in RS, with families and caregivers during home visits, in therapeutic sessions, and in consultation. The world has experienced a collective trauma. The infestation of racism and lack of resources cannot be ignored. IEC professionals must work to be intentional to honor differences and the experiences of the family, caregiver, child, and community.

RS and IEC services that make intentional space to examine the impact of race, culture, and social inequities can act as a charging station to fuel providers as they strive to engage in relationship-based work with caregivers and families. Promoting professional wellness during times of crisis is critical. The field is calling for more diversity in scholarship, research, and the workforce (Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, n.d.; Iruka et al., 2021). Systemic racism, social injustice, and the pandemic have prompted IEC providers to promote a more equitable and inclusive workforce to address the needs of diverse family structures (Irving Harris Foundation, 2018). Recruitment, training, and support of a more diverse workforce mean the impact of race, diversity, and equity within all relationships, including the supervisory relationship, must be considered.

Guiding Principles of Diversity-Informed RS

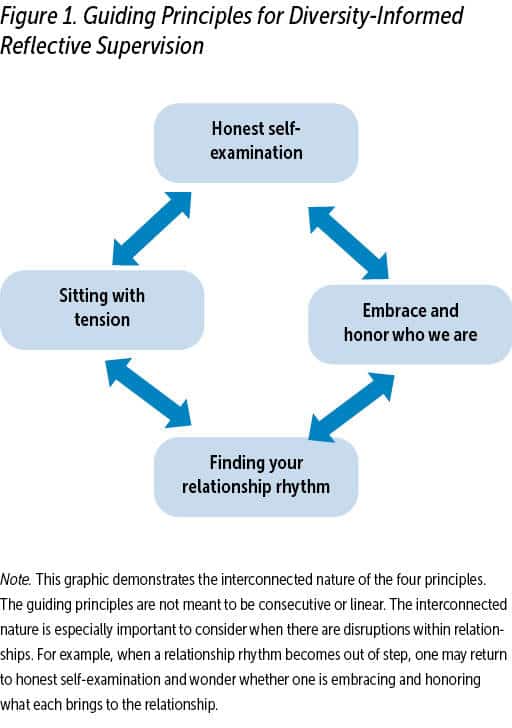

In my (KW) ongoing journey to place race and diversity at the center of IEC work, I developed four Guiding Principles of Diversity Informed Reflective Supervision (see Figure 1). The four principles support diversity-informed RS by promoting the development of trusting, safe, and nurturing relationships that allow all participants to bravely engage in shared vulnerability and genuine expression of emotional responses to their work. As I have continued to evolve in my own cultural growth and contemplation, I was keenly aware that co-creating a space for conversations about race was often missing (Wilson et al., 2018). I am grateful to see that these conversations are beginning to happen with more frequency and urgency in the field.

The four guiding principles help IEC professionals to examine the impact of diversity and support “diversity wellness.” Diversity wellness is a continuous process that strives to honor the unique values, beliefs, and perspectives of human beings. Intentional dialogue and a shift in the awareness of how race, culture, and identity influence what IEC professionals bring to their relationships needs to be included in RS. The four Guiding Principles of Diversity-Informed Reflective Supervision are: (a) Honest self-examination; (b) Embrace and honor who we are; ( c) Finding your relationship rhythm; (d) Sitting with tension.

The following is a brief description of an exchange between Ava, a Black woman, who has been working as an IEC home visitor for several years, and her supervisor, Selina, who also identifies as a Black woman. Ava and Selina have worked together for 4 years. Over this time, they have co-created reflective space where they have been able to talk about what they each bring to their relationship. Selina invites curiosity, deeper thinking, and reflection that has informed Ava’s understanding of herself and what the families with whom she works may be experiencing. Although tentative at first, Ava has also explored how her own cultural narrative impacts her emotions and responses.

This interaction took place soon after Ava and Selina returned to in-person RS meetings and Ava returned to in-person home visiting following virtual communications in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. This vignette will be used to reflect on the guiding principles and how they can be used within practice.

Ava comes to RS feeling very frustrated with one of her families. She says that the mother, who is also Black, is very unresponsive to services and doesn’t respond to her baby. She says she has witnessed the 15-month-old toddler make several attempts during visits to offer Mom a toy, and Mom’s response is to say “Go play” or she turns the TV on. Ava also shares that Mom doesn’t talk with her and most of her time as a provider has been observing and being curious about what Mom and her toddler might be experiencing. Selina listens carefully, and she invites Ava to say more about what the visit was like for her and what might be happening with Mom and toddler.

Ava is quiet for a moment and then shares that she has noticed an overall change in the families she has been working with. Their energy feels hopeless and what has worked before when offering emotional support to families has felt harder. She goes on to talk about the COVID-19 pandemic and how she has experienced more anxiety, dysregulation, and depression with families. She says it’s hard to be with families, who have been exposed to systemic racism, and now feel more isolated and unheard than ever before. Selina wonders if the toddler’s unsuccessful attempts at engaging her mother paralleled Ava’s own frustration of not feeling heard. Ava begins to cry as what Selina proposed sunk in. Ava tries to put into words the fear, isolation, and anxiety she has felt. It feels overwhelming, and the ease she felt when entering relationships has been replaced with apprehension and ambivalence. She has worked harder to build trust and address her own assumptions about and what they need.

Ava was offered space to think about her work and examine her feelings which included feelings of frustration with the parent and underpinnings of the impact of diversity, race, and culture. The ease in which this dyad was able to engage in reflection can also happen when the supervisor and supervisee share the same race. The key is to be able to acknowledge that, even when they aren’t openly discussed, race, culture, and identity are significant to services.

Building relationships is a process that involves feelings of safety, bravery, and vulnerability. Photo: shutterstock/fizkes

It is important to hold in mind how Ava has also been impacted by racial unrest and trauma from the pandemic. An invitation to talk about her frustrations and the importance of self-care should be encouraged. In addition, due to the pandemic, the ways she can intervene with her families has changed drastically and the meaningful connections she had with peers have been removed because of social distancing. The impact of the loss of connections with families, children, and colleagues has been difficult for Ava to put into words, yet is important to examine to honor Ava’s experience and inform her work with this parent–child dyad.

Honest Self-Examination

Honoring diversity is an ongoing process of continuous reflection including the examination of values, beliefs, behaviors, and biases. It can be difficult to explore bias and privilege in RS, because one may feel shame in acknowledging their assumptions are often founded in negative stereotypes and painful experiences (Menakem, 2017). Holding a nonjudgmental stance is integral in RS (Barron et al., 2022; Tomlin et al., 2014), but how can one be nonjudgmental without acknowledging the experiences and people who may have been judged? Anchored understanding of diversity in RS posits that the supervisee’s values and beliefs are as meaningful as the supervisor’s. Together the supervisor and supervisee actively engage in honest self-examination of what hinders their ability to offer respect, reciprocity, and responsiveness to each other (Barrera & Kramer, 2017).

In his book, My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending our Hearts and Bodies (2017), Resmaa Menakem suggested that people of all races are impacted by intergenerational trauma and ethnic stress. Historical and current systemic racism and social injustice carry both physiological and psychological scars. The feelings of being misunderstood and unseen carry wounds that invade the co-created space in RS if not addressed (Wilson et al., 2021). Differences for some are seen as threatening. If within the RS relationship the supervisee and supervisor can carefully examine the wounds and scars, what is brought to RS can be more valuable.

Embrace and Honor Who We Are

When people honestly examine themselves and what they bring to relationships, they then must embrace and honor who they are, which includes their race, culture, beliefs, and biases. One cannot honor another until one embraces and honors oneself. A sense of identity is formed through lived experiences which become part of one’s narrative. An important aspect of relationship building is honoring and acknowledging race in a way that invites respectful curiosity, recognizing that in fact it is one’s lived experiences that make one’s existence evidence-based (Barrera & Kramer, 2017). That is, lived experiences are the evidence of who one is, and are unique to every individual. Embracing the evidence and reality of who we are is critical to relationship-based work. If IEC professionals cannot embrace themselves—even the parts that they may wish to change—it is difficult to accept the evidence of others. In RS, the supervisor and supervisee are evidence-based and their lived experiences will impact their responses in the relationship.

In the vignette, Ava talked about how her interactions with families did not feel as comfortable as they had in the past. She noted her difficulty with engagement. Consider the supervisor within the vignette. What does she bring to this relationship? Selina’s early relationship experiences didn’t encourage the expression of strong emotions such as anger or sadness. Early in their RS relationship, these early experiences could have influenced Selina’s response to Ava. She may have minimized Ava’s emotional experience and focused on the parent—child relationship and the mother’s behaviors. As a result, Selina’s approach may be to respond with humor and idealism which could feel dismissive to Ava. Selina’s own supervision could help her to make this important connection. Selina would realize that at times she was unable to validate another’s expression of anger because she had not been encouraged to embrace all her emotions. By learning to value her own emotions and feelings, she could offer a sturdy holding environment for Ava where deep feelings can be explored.

Finding Your Relationship Rhythm in RS

Embracing and honoring diversity is a dance where partners build respect and positive intent, creating space for building trust and shared vulnerability. This partnership evolves through openness and curiosity that encourages each to be flexible. Flexibility within relationships allows for open mindedness and invites the exploration of additional perspectives and new ways of being.

Recruitment, training, and support of a more diverse workforce means the impact of race, diversity, and equity within all relationships, including the supervisory relationship, must be considered. Photo: shutterstock/SeventyFour

Each relationship in RS brings its own uniqueness. As the relationship deepens, the supervisee and supervisor will begin to choreograph more intricate steps to maintain their rhythm. In this way they are learning from and with each other. Again, each person brings their own narrative, remembering that disruptions occur naturally in any relationship. It feels important to address them when they arise, to avoid making assumptions. The relationship in RS is a collective experience. We honor ourselves so we can honor what has been carefully choreographed in this space. When change needs to happen and repairs need to be made it is within the context of mutual respect and recognition of valuable contributions made by the supervisor and supervisee.

Sitting With Tension in RS

The process of honoring diversity begins with valuing the experiences of others. This can be challenging and uncomfortable when one’s experiences and beliefs are different from others. Sitting with tension includes suspending judgment and acknowledging another’s behavior as meaningful and necessary, and true to their experience.

To endure the tension, IEC work strives to co-create trust by going at a pace that can be tolerated, noting the discomfort felt within the relationship. When safety is felt, opportunities for bravery and exploration happen. Barrera and Kramer (2017) defined Third Space as a strategy crafted to address differences posed by diverse perspectives. In RS, Third Space promotes the co-development of options within which the strengths of the supervisor’s perspective complement the strengths of the supervisee. As experts of their own perspective, they create options that honor both ideals. The balance of power creates vulnerability, but also calls for partners in the relationship to be accountable and invested in outcomes. In the vignette, Ava expressed difficulty in her developing relationship with the family. This can be challenging to hear without offering problem-solving and solutions. Selina learned to remain curious and quietly supported Ava as she gained clarity and comfort in the RS space.

Conclusion

Infusing diversity-attuned practices in the IECMH field offers powerful support to families with young children and service providers. Research has shown that RS enhances the IECMH workforce by supporting staff retention and promoting efficacy and confidence among service providers (Heller & Ash, 2016; Shea et al., 2016). More brave conversations about the impact of power, privilege, and systemic racism in RS strengthen outcomes and the workforce (Stroud, 2010; Wilson et al., 2021). These conversations require safety, bravery, and a willingness to be vulnerable.

Ava and Selina developed a relationship over time that allowed for this bravery. It strengthened their supervisory relationship. There will be times when supervisees and supervisors lose their rhythm. When this happens, it is important to reassess, examine the choreography, and return to the principle of honest self-examination. Doing so allows for authentic discussions about why strong feelings are evoked. Honest self-examination helps IEC professionals think about all of who they are and what they are bringing to this work—including the uncomfortable parts and parts they want to change. When one begins to feel out of step, especially when regarding race and diversity, one may minimize the impact and their responses to avoid tension. However, this can create more tension and feelings of discomfort.

Strong relationships over time can recognize and sit with tension in a way that supports conversation and honors perspectives. Acknowledging the tension and working together allow for the choreography of new dance steps. Using these four guiding principles, IEC professionals can enhance the supervisory relationship, which then helps the practitioner to support caregivers and families, ultimately strengthening the infant’s attachment relationship and developmental progress. These principles align with the Diversity-Informed Tenets and remind IEC professionals to embrace diversity and offer equitable, inclusive services to support the needs of caregivers, families, young children, and professionals.

Author Bios

Karol Wilson, LMSW, IMH-E®, was one of the program supervisors for the Partnering With Parents program at Starfish Family Services until she retired in June 2021. Ms. Wilson has been a part of the infant and early childhood mental health field for more than 25 years as a home visitor, mentor, program supervisor, trainer, and individual and group reflective supervisor/consultant. She is co-author of 3 published articles and was an author on two chapters in a recently published book: Therapeutic Cultural Routines to Build Family Relationships: Talk, Touch and Listen While Combing Hair, edited by Marva Lewis and Deborah Weatherston. Ms. Wilson now works as an independent reflective consultant and continues to provide trainings and individual reflective supervision. She takes pride in being one of the first Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health (MI-AIMH) Diversity Fellows and is the first African American to achieve endorsement by MI-AIMH as an Infant Mental Health Mentor (Clinical).

Carla C. Barron, PhD, LMSW, IMH-E®, is the clinical coordinator and assistant research professor for the Infant Mental Health Program at Merrill Palmer Skillman Institute at Wayne State University. Dr. Barron facilitates a graduate-level infant mental health seminar, engages in community-based research, and provides professional development trainings on a variety of topics including reflective supervision/consultation and home visiting ethics and boundaries. She facilitates reflective supervision/consultation with infant and early childhood professionals across Michigan and nationally. She received her doctorate in social work from Wayne State University and is endorsed as an Infant Mental Health Mentor-Clinical by the Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Suggested Citation

Wilson, K., & Barron, C. C. (2022). Honoring race and diversity in reflective supervision: Guiding principles to enhance relationships. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(4), 14–20.

References

Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (n.d.). A statement from the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. link

Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1967). Infancy in Uganda: Infant care and the growth of attachment. The Johns Hopkins Press.

Barrera, I., & Kramer, L. (2017). Skilled dialogue: Authentic communication and collaboration across diverse perspectives. Balboa Press.

Barron, C. C., Dayton, C. J., & Goletz, J. L. (2022). From the voices of supervisees: What is reflective supervision and how does it support their work (Part I). Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 207–225. link

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment. Basic Books.

Fenichel, E. (1992). Learning through supervision and mentorship to support the development of infants, toddlers and their families: A source book. ZERO TO THREE.

Fortuna, L. R., Tolou-Shams, M., Robles-Ramamurthy, B., & Porche, M. V. (2020). Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 443-445. link link

Heller, S. S., & Ash, J. (2016). The Provider Reflective Process Assessment Scale (PRPAS): Taking a deep look into growing reflective capacity in early childhood providers. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 37(2), 22–29.

Iruka, I. U., Lewis, M. L., Lozada, F. T., Bocknek, E. L., & Brophy-Herb, H. E. (2021). Call to action: Centering blackness and disrupting systemic racism in infant mental health research and academic publishing. Infant Mental Health Journal, 42(6), 745–748.

Irving Harris Foundation. (2018). The Tenets: Diversity-informed tenets for work with infants, children, and families. link

Jones Harden, B. (2010). Home visitation with psychologically vulnerable families: Developments in the profession and in the professional. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 30(6), 44–51.

Karen, R. (1994). Becoming attached. Oxford University Press.

Marshall, J., Kihlström, L., Buro, A., Chandran, V., Prieto, C., Stein-Elger, R., … & Hood, K. (2020). Statewide implementation of virtual perinatal home visiting during COVID-19. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 1224–1230.

Menakem, R. (2017). My grandmother’s hands: Racialized trauma and the pathway to mending our hearts and bodies. Central Recovery Press.

O’Rourke, P. (2011). The significance of reflective supervision for infant mental health work. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32(2), 165–173.

Pawl, J. (1994). On supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 15(3), 21–29.

Ribaudo, J. (2021). What about the baby? Infancy and parenting in the COVID-19 pandemic. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 1–15, DOI:10.1080/00797308.2021.2001251. link

Schafer, W. (2007). Models and domains of supervision and their relationship to professional development. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 28(2), 9–16.

Shea, S. E., Goldberg, S., & Weatherston, D. J. (2016). A community mental health professional development model for the expansion of reflective practice and supervision: Evaluation of a pilot training series for infant mental health professionals. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 653–669. link. link

Stern, J. A., Barbarin, O., & Cassidy, J. (2021). Working toward anti-racist perspectives in attachment theory, research, and practice. Attachment & Human Development, 1–31. link. link

Stroud, B. (2010). Honoring diversity through a deeper reflection: Increasing cultural understanding within the reflective supervision process. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 31(2), 46–50.

Thompson, C. E., & Carter, R. T. (1997). An overview and elaboration of Helms’ Racial Identity Development theory. In C. E. Thompson & R. T. Carter (Eds.), Racial identity theory: Applications to individual, group, and organizational interventions (pp. 15–32). Routledge.

Tomlin, A. M., Weatherston, D. J., & Pavkov, T. (2014). Critical components of reflective supervision: Responses from expert supervisors in the field. Infant Mental Health Journal, 35(1), 70–80. link. link

Weatherston, D. J., & Barron, C. (2009). What does a reflective supervision relationship look like? In S. Scott Heller, & L. Gilkerson (Eds.), A practical guide to reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE.

Weatherston, D. J., Ribaudo, J., & Michigan Collaborative for Infant Mental Health Research. (2020). The Michigan infant mental health home visiting model. Infant Mental Health Journal, 41(2), 166–177.

Weatherston, D., & Tableman, B. (2015). Infant mental health home visiting: Supporting competencies/reducing risk, Manual for Early Attachments: IMH Home Visiting®. Michigan Association for Infant Mental Health.

Wilson, K. A. (2021). Infant mental health practice and reflective supervision: Who we are matters. In M. L. Lewis & D. J. Weatherston (Eds.), Therapeutic cultural routines to build family relationships (pp. 115–122). Springer.

Wilson, K. A., Weatherston, D. J., & Hill, S. (2021). Introduction to reflective supervision: Through the lens of culture, diversity, equity, and inclusion. In M. L. Lewis & D. J. Weatherston (Eds.), Therapeutic cultural routines to build family relationships (pp. 75–83). Springer.

Wilson, K., Barron, C., Wheeler, R., & Jedrzejek, P. E. A. (2018). The importance of examining diversity in reflective supervision when working with young children and their families. Reflective Practice, 19(5), 653–665.