Crissie McMullan, Mountain Home Montana, Missoula, Montana

Eric Lucas, Hopewell Health Centers, Inc., Athens, Ohio

Hindolo Pokawa, Sierra Leone Foundation for a New Democracy, Mondema, Sierra Leone

Abstract

Child- and family-serving programs in community-based settings wield tremendous power for improving the lives of infants and toddlers. In this article, three authors, from Ohio, Montana, and Sierra Leone, describe the principles of adaptive leadership and will share their real-world applications. Their stories explore critical questions for leading community-based organizations: How do leaders of community-based efforts build leadership among families and other program participants? How do they incorporate equity, diversity, and social justice into both their programs and their process? How do they extend their influence and impact beyond the local? And, perhaps most important, how do they sustain themselves amid competing pressures and priorities?

Young children and their families are valuable members of the community. When needs arise in these families, community-based programs are poised to respond with appropriate resources and support. In order to effectively leverage the potential of community programs, adaptive leaders are needed who have a deep understanding of the populations served, who have the capacity to build trust and partnership with participants, and who can visualize longer-term goals and visions that sustain initiatives. Leaders in community-based settings also have the power to address issues of equity and access by building programs that value inclusiveness and cultivate staff who affirm the value of diversity and difference in the families served.

This article examines three examples that highlight the power of community-based programs. Each program is impacting local communities with a level of breadth and innovation that has garnered local and national (even global) attention. Moreover, each program example highlights the role of adaptive leadership; emphasis on equity, diversity, and inclusion; and sustaining innovation in the face of continuous external pressure from funders and competing priorities. In reviewing these examples, readers are encouraged to see the potential in their respective settings and the opportunities to also leverage community-based programs in service of infants and toddlers.

Appalachia Ohio, United States: Hopewell Health Centers, Inc.—Erin Lucas

Imagine a community that works together, ensuring that caregivers and professionals have what they need to grow healthy children who thrive. Hopewell Health Centers, Inc. (HHC) is working to make this a reality in rural, southeast Ohio. HHC is a Federally Qualified Healthcare Center providing medical, dental, and behavioral health care through more than 20 school and community locations in Appalachia Ohio. These communities have high rates of chronic health needs, as expected in populations exposed to generational poverty and high rates of adverse childhood experiences. This stress has led to other public health problems such as high rates of tobacco use, exposure to family violence, and, most recently, an explosion of opioid use and abuse. Ohio is at the center of the opiate epidemic, ranking second behind West Virginia in opiate overdose deaths in 2017, with the HHC service region exceeding state rates (CDC National Center for Health Statistics, 2020). Suicide rates are 26% higher than the rate in non-Appalachian counties (Appalachian Regional Commission, 2017). As a result, young children are facing increasing risk for exposure to trauma and developing behavioral health concerns. Neonatal abstinence syndrome is on the rise: of the counties in Ohio with the highest rates, 9 of the top 10 are in Appalachia. Babies born in this region are almost twice as likely as the average Ohio newborn to be diagnosed with neonatal abstinence syndrome (Ohio Children’s Defense Fund, 2016). In response to these serious health threats, HHC is bringing together caregivers and professionals to seek answers for how to help children impacted by addiction and other trauma.

Complex problems need complex solutions, including a cohesive system of care. Throughout the journey as a ZERO TO THREE Fellow, participants were challenged to explore how they might provide leadership that would build on the strengths of already established systems while also rising to the new challenges in communities. Three core responsibilities of an adaptive leader are to provide direction, protection, and order (Heifetz, Grashow and Linsky, 2009).

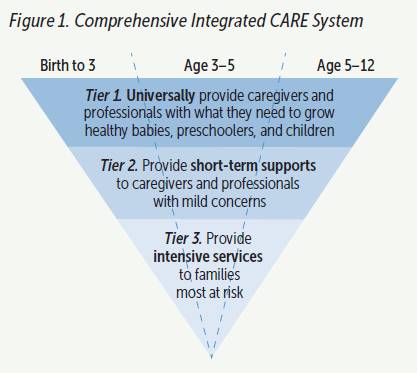

In order to provide direction, protection, and order through the process of change, HHC Early Childhood Programs began by designing a framework to guide the work. The Comprehensive Integrated CARE System was designed to advance access to affordable, high-quality, integrated health care for children from birth to school age The three-tiered approach to care outlined responsibilities for three specific age populations.

The Comprehensive Integrated CARE System, shown in Figure 1, provided a structure for communication and collaboration within and across systems. The formalization of this structure by the organization led to an internal agency structure to support this work. Designating coordinators for each age range helped provide the protection needed to ensure the work was not temporary in nature, but rather ensured the long-term commitment of the agency.

Fellows were also urged to consider the gains as well as the losses associated with significant changes (Heifetz et al., 2009), such as those we were undertaking at HHC. Adopting a model and structure to guide and house the work moving forward led to a shared plan to move the vision forward as well as role clarity within the team. While this adoption was helpful and necessary to advance the work, it also resulted in loss: staff lost the comfort of their previously established routines and approaches as well as loss of security as a result of moving into unknown services, developing processes and formalizing procedures. Realizing through the Fellowship that some sense of loss was inevitable, regardless of how positive the solution appeared, the Early Childhood team learned the importance of taking time to discuss and share feelings of both excitement and of fear to give voice to the discomfort as a natural phase of the transition.

After formalizing the model and structure for ensuring access to affordable, high-quality, integrated health care for children from birth to school age, HHC’s Early Childhood team began to create space within the weekly routine to consider adaptive challenges. Adaptive challenges were defined as challenges that are “typically grounded in the complexity of values, beliefs, and loyalties rather than technical complexity and stir up intense emotions rather than dispassionate analysis” (Heifetz et al., 2009, p. 70). Reflective supervision and regular meetings of team leadership provided time to think through challenges each leader encountered.

Similar to the concept of trauma-informed care where there is a shift from thinking about what is wrong with a person to thinking about what happened to that person, when applied at a system level, there was a shift to think more about what was happening within the system to cause the current outcome. With this approach, team members developed strategies to leverage relationships within the extended communities, appeal to the priorities of partners, and learn to use a common language for talking about the work across and within systems of care. In addition, the team developed a) leadership skills which increased confidence, b) more solid relationships with community partners, and c) collaborative work within and across systems advancing access to care for children and families.

In the work to create comprehensive access to services for children birth to 3 years old, staff members learned of the increasingly difficult behavior challenges early intervention providers were facing on home visits. Together, team leaders decided that assigning a behavioral health provider for each case would significantly strain the already limited infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) capacity. Instead, HHC developed a model for providing ECMH consultation to early intervention teams. As a result, early intervention providers are equipped with skills to promote social–emotional development and respond to challenging behaviors. With these valuable gains to teams and the early childhood community came a shift in the way things worked on the HHC team. This change led to the recognition that with every shift in time investment, leaders must consider not only the direction they are moving their energy, but the impact on the system that was receiving the energy. The time spent advancing these partnerships resulted in leaders within the HHC team reporting less connection to others within the team, less time dedicated to existing work/partners, and difficulty teaching direct service workers the language of multiple systems within the community. Identification of this change has allowed team leaders to create plans to address the impact within their future work, rather than ignore the effect.

Advancing systems-level change with adaptive leadership has been a journey full of highs and lows, requiring a high level of commitment of team leaders at HHC. In partnership with the Whole Child Matters initiative from the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, the team has advanced access to IECMH services across Appalachia Ohio including the implementation of HealthySteps within their integrated care settings. Hopewell’s work with state partners has been recognized by awards such as the Ohio Early Childhood Mental Health Master Trainer of the Year and the Community Collaboration Award for the early intervention program. Further, the IECMH consultation in early intervention model HHC developed was funded for replication across the state through an IECMH Expansion Grant.

Finally, the team has worked with local school districts to expand the consultation model through school age and has partnered with local Alcohol Drug Addiction and Mental Health Services Boards and Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services Bureau of Children, Youth, and Families to share lessons learned and develop strategies to replicate the model statewide. These accomplishments demonstrate evidence of a collaborative model, implementing concepts of adaptive leadership, which the ZERO TO THREE Fellowship nurtured, allowing the fellowship to impact much more than a single Fellow, but rather an entire early childhood system in Appalachia Ohio. Realizing a vision as complex as ensuring access to affordable, high-quality integrated care for children from birth to school age in an underserved and underresourced area such as Appalachian Ohio is a tall order. Together with their community, HHC Early Childhood Programs is rising to the challenge.

Montana, United States: Mountain Home Montana—Crissie McMullan

Mountain Home Montana provides a safe home and nurturing community where young mothers discover their strengths and their children thrive. Though young, the families here already have a long list of barriers to their well-being. Of the young mothers Mountain Home served last year, 40% were a part of the foster care system themselves as children, 60% were homeless, and 90% had a history of serious childhood trauma (Mountain Home Montana, 2019). The staff aim to meet them where they’re at. Housing, education, and employment programs meet a family’s basic needs and build independence, while the mental health center strengthens coping skills and fosters healing from past trauma.

Montana has one of the highest suicide rates per capita in the nation, in part due to a culture of fierce independence and stigma around asking for help. Photo: Jon Bilous/shutterstock

My time as a ZERO TO THREE Fellow centered around improving Montana’s mental health system to benefit the families at Mountain Home and statewide. Effective leaders should correctly distinguish between technical problems and adaptive challenges (Heifetz et al., 2009). A technical problem may be complex, but it has a known solution that can be applied within the current mode of operating. In contrast, an adaptive challenge requires significant changes to the entire system, including the beliefs and priorities of individuals within the organization.

Multiple adaptive challenges present barriers to young families in the Mountain Home community around mental health. For one, access; especially cost. Although Mountain Home accepts Medicaid, during the course of my term as a ZERO TO THREE Fellow, the funding for Medicaid expansion was being intensely debated by Montana’s state legislators. Virtually none of Mountain Home’s clients could afford mental health care without this critical public insurance. But Mountain Home had always focused only on direct service: for our staff to make the journey from Missoula to the state capitol in Helena was more significant than a simple 2-hour drive over the mountains. The board of directors and leadership staff had to carefully weigh out the potential benefits, such as the impact on clients, as well as the losses, such as potentially upsetting donors or overwhelming leadership staff with the additional workload.

Inspired in part by the ZERO TO THREE Fellowship’s encouragement to think at the systems level, Mountain Home staff decided to accept the adaptive challenge. We wrote letters, organized phone banks, and testified at the state capitol about the importance of Medicaid expansion. Because public health services such as these cost money, we also joined a coalition led by the Montana Budget and Policy Center that advocated to increase revenue through a more fair tax system. In Montana, those with incomes in the top 1% pay a smaller portion of their income in taxes than those with incomes below $18,000.

Happily, Medicaid expansion was approved. The slim margin of the win indicated that every contribution—including Mountain Home’s—had been necessary. Unfortunately, the income generating bill failed. Increasing taxes is rarely popular, even when the goal is to increase fairness. Perhaps the biggest success was that Mountain Home’s board and staff got a stronger sense of how we could leverage our expertise as direct service providers to exponentially increase our impact.

I also focused on a second adaptive challenge around mental health care: stigma. Montana has one of the highest suicide rates per capita in the nation, in part due to a culture of fierce independence and stigma around asking for help. To address cultural stigma, Mountain Home staff again had to think beyond our own direct service model. We developed a campaign called “Strong Moms Ask for Help,” which included social media videos, outreach events, and continues now as a monthly newsletter.

My third, and final, adaptive challenge: efficacy. Mental health care is still evolving in its ability to consistently produce successful outcomes even when using best practices. To better understand our impact and to set clear goals to improve, Mountain Home staff adopted a robust evaluation tool measuring 40 different aspects of family well-being in 2018. By 2019, we had our first year of data, and the Mountain Home leadership team and board took a deep dive into the results. Many of our numbers were incredibly exciting. For example, within just 6 months of care almost 80% of children had improved their overall health through appropriate well care, sick care, dental care, and immunization (Mountain Home Montana, 2018).

The data also revealed areas to improve. Reflecting with the staff and board, the leadership team realized that outcomes are directly tied to staff performance. Mountain Home’s high rate of staff turnover due to inadequate pay was a direct hindrance to the success of the programs. Clearly, Mountain Home needed to pay more, but this seemed an insurmountable problem: where would the money come from? However, as I continued to think with the leadership team about the underlying issue and how central it was to Mountain Home’s mission, a new perspective emerged. Improved rates were not a luxury that Mountain Home could never afford, and instead were a necessity that I and the leadership team must prioritize.

As the person ultimately responsible for the organization’s budget, I also had to increase my risk tolerance, as suggested in Adaptive Leadership. “Confront the fear that understandably has been holding you back…Start wherever you are on the risk-averse spectrum” (Heifetz et al., 2009, p. 280). My fear, to put it succinctly, was that we would run out of money. Not only was that a professional concern, but one that triggered my own childhood experience of financial instability, a deeply ingrained terror of not having enough. Partnering with Mountain Home’s director of development and planning, I created multiple spreadsheets projecting how Mountain Home could raise the necessary funds. While the plans scared me, they were achievable enough that the director and I decided to go for it. In the fall of 2019, Mountain Home implemented a new minimum wage of $15/hour for all direct care workers and increased the wages of all other staff to at least the 80th percentile of the market rate for their position. Altogether, this increased expenses by more than 10% annually.

So far, it’s worked. Just as I and the leadership team had hoped, the increased pay rates have improved overall staff morale, particularly for those previously paid the least. Of course, even positive change can be hard for some, so I was surprised when a few staff were upset that the new pay rates narrowed the size of the previous gap between supervisors and direct care staff. However, everyone eventually adjusted, and the Mountain Home staff are optimistic about the ultimate impact on the families. The process of change can be compared to that of a pressure cooker (Heifetz et al., 2009). Leave it too long, and the ingredients turn to mush. Too much heat, and the whole thing explodes. But leaving the pot cool to the touch won’t work either. The ZERO TO THREE Fellowship gave me the opportunity to reflect on my role not only as the one adjusting the dials on the cooker, but also as a participant on the inside. I feel the heat and pressure, too! Mastering the art of adaptive leadership will be an ongoing process throughout my career, but how fortunate to have the ZERO TO THREE community to learn from and walk alongside. Together, we can truly make the world better for children and families.

Sierra Leone, Africa: Sierra Leone Foundation for a New Democracy—Hindolo Pokawa

Leadership is a process; it is constant negotiation with the everyday undertakings in life, in homes, in work places, and in the environment. Leadership is perhaps the one thing in common most people have. While this may be true, the view at which leadership is seen can be very different. Taking a bird’s eye view of what leadership in your sphere of influence could look like is very different from how others will experience what leadership means to them. This differing perspective leads to the question of how leaders problematize situations and what kind of solutions they tend to prescribe to address those issues. From Montana to Ohio, to Sierra Leone, leadership qualities to address infant mental health have different approaches; in the case of Mondema, a small village in Sierra Leone, villagers had an idea to address a major issue that was taking place in their community. The community noticed that many members of their community were migrating to the big city to look for jobs and to provide better access for their children’s education. The elders in the village quickly realized that one of the major reasons people were moving out of the village was the lack of a good educational system in the village—especially for the children in the younger age group, from 2 to 5 years old.

There was no one who they could turn to for support or a partnership that could bring a meaningful change for their lives. So, as community members gathered, talked, and brainstormed, they approached Sierra Leone Foundation for New Democracy (SLFND) to partner with them to build Sierra Leone’s first stand-alone village preschool in the country. It was their own collective will to make a change for the lives of their children that promoted the creation of Dovalema Early Childhood Cooperative in Mondema (see Box 1 and Box 2). The villagers could have chosen to start with something else or start just with a handful of children, but they decided to start with care for the children as a main focus. They decided to build a new structure for all the village’s children rather than starting small; they felt there was no fair criteria on which to select participants. Without salaried staff or government or philanthropic grants, SLFND mobilized more than 150 villagers, 30 international volunteers and partners, and hundreds of donors who built Dovalema Early Childhood Co-op amid Ta-Valema Permaculture Farm and Learning Lab. Nearly all villagers enrolled their children immediately.

The flag of Sierra Leone standing tall with Dovalema school children playing outside during recess. Photos: Hindolo Pokawa

Dovalema children bringing out their imagination. Photos: Hindolo Pokawa

Eleven secondary-school graduates from the community who had no opportunities for education or employment within the village have been recruited, selected, and are being trained at an accredited post-secondary institution while serving as teachers at Dovalema. They further develop professionally through trainings facilitated by early childhood education volunteers, focusing on special needs, trauma, and culturally specific education.

BEFORE: Dovalema Early Childhood Education Center—Sierra Leone’s first village stand-alone preschool. Photos: Hindolo Pokawa

AFTER: Dovalema Early Childhood Education Center. Photos: Hindolo Pokawa

SLFND works closely and coordinates efforts with the primary schools in the village, the clinic, church, and mosque. It has a working relationship with the chief and has engaged the national government, which responded very positively to SLFND’s work. The work’s sustainability is illustrated by the investments made by local businesses and the interest expressed by neighboring villages and countries. These include a bio-fil digester toilet and two smoke-free stoves that were manufactured by Sierra Leoneans in Sierra Leone.

Success required the leadership of one person dreaming and turning the dream into the community dream. In the process, the preschool and the efforts to strengthen the community have been recognized locally, nationally, and even at a global scale. When the focus is in service of children, partnership with collective action can move entire communities as seen in the efforts of SLFND.

Conclusion

The three examples in this article highlight the opportunities taken in diverse settings that share the goal of promoting the health and well-being of very young children and their families. There is no one formula that can make a community or community program stronger or more effective than another, but it is essential to cultivate early childhood leaders and community partners with shared values and a common vision who can leverage their power to create effective community programs for very young children and families.

Learn More

Back Issues of Strong Moms Ask for Help Newsletter

https://mountainhomemt.org/category/blog

Sign Up for the Mountain Homes Newsletter

https://mountainhomemt.org/newsletter

Like us on Facebook, Hopewell Health Centers

Author Bios

Crissie McMullan, MS, is executive director of Mountain Home Montana, a shelter and mental health center for homeless young mothers and their children located in Missoula, Montana. In Ms. McMullan’s first 4 years at Mountain Home, she increased numbers of mothers and children served by 60%, instituted trauma-informed policies and procedures, and earned media recognition ranging from local television to The New York Times. She also spearheaded a campaign to reduce the stigma around mental illness called “Strong Moms Ask for Help.” Ms. McMullan first began supporting children and families as an advocate for local and healthy food in schools. In that role, she co-founded a national FoodCorps, which has since improved nutrition for hundreds of thousands of children in more than 15 states.

Erin Lucas, LISW-S, is early childhood programs director at Hopewell Health Centers, Inc., a Federally Qualified Health Center, providing integrated health care in southeast Ohio. Ms. Lucas has a vision for creating effective collaboration within and across systems to meet the needs of young children and families in rural Appalachian Ohio. Ms. Lucas directs the work of wellness programing, early intervention services, infant and early childhood mental health consultation and therapy, training, and consultation to schools to promote the integration of trauma-informed care. In addition to her role at Hopewell Health Centers, Ms. Lucas serves as an adjunct instructor in the social work program at Ohio University, growing the field of social workers prepared to serve in rural America. Ms. Lucas received her undergraduate degree in biological sciences and Spanish, and her master’s in social work from Ohio University in Athens, Ohio.

Hindolo Pokawa, MA, is founder and executive director of the Sierra Leone Foundation for New Democracy. As a child in Sierra Leone, Mr. Pokawa experienced the brutal violence, economic destruction, and social disintegration of Sierra Leone’s civil war. After finishing high school as an adult in Zimbabwe, where he fled once the war escalated, he came to the United States and earned his undergraduate degree in political science and global studies, with a minor in African-American studies, focusing on peace and governance. Mr. Pokawa has since completed a master of liberal arts degree, for which he focused on the relationship between the mining industry and literacy in rural Sierra Leone. Mr. Pokawa is working on a master’s in comparative and international development education, where he is focused on the sustainability of educational policy and programs in countries like Sierra Leone, 70% of whose budgets are financed through foreign aid.

Suggested Citation

McMullan, C., Lucas, E., & Pokawa, H. (2020). Innovative leadership in community-based programs for young children and famillies. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(5), 21–27.

References

Appalachian Regional Commission. (2017). Key findings: Health disparities in Appalachian Ohio. Retrieved from source

CDC National Center for Health Statistics. (2020). Drug overdose mortality by state (2017). Retrieved from source

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., & Linsky, M. (2009). The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Mountain Home Montana. (2018). Annual report, 2018. Missoula, MT: Author.

Mountain Home Montana. (2019). Annual report, 2019. Missoula, MT: Author.

Ohio Children’s Defense Fund. (2016). Ohio’s Appalachian children at a crossroads: A roadmap for action. Columbus, OH. Retrieved from source