Grace Whitney, SchoolHouse Connection, Washington, DC

Marsha Basloe, Child Care Services Association, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Abstract

The articles in this issue of the ZERO TO THREE Journal provide a sampling of policies, practices, challenges, and opportunities relating to homelessness that are facing the infant–toddler field today and the impact of persistent mobility and unsafe housing conditions on early development and family relationships. Articles span several service sectors including early care and early childhood programs, parenting supports, housing, pediatrics, and pregnant and parenting youth among others. The authors provide suggestions for continuing to grow capacity to address these complex issues and the critical need to include an understanding of homelessness into all aspects of child development and family services.

Homelessness continues to be a persistent life experience for too many infants, toddlers, and their families. What researchers know from observations and data is that young families continue to struggle to establish themselves in financially secure households and that the impact of such personal challenge shapes where they live and how well they can provide for their children. For the child, their family circumstances will greatly determine their experience of relationships and their own potential in life. Homelessness is just one factor in a cluster of hardships families and children face, and homelessness is generally not an isolated incident nor quickly and simply resolved. Although homelessness is not a new phenomenon, early childhood professionals are just beginning to explore the real and lasting impact of homelessness and how to specifically address the needs of infants and toddlers experiencing homelessness who—until quite recently—have been essentially invisible. Housing and homeless service providers have often sought child care so that parents could go off to work, as if reserving a parking space for a car, without knowing about subsidized resources that might be available and without understanding that quality matters greatly for vulnerable young children. Some adult and family service programs still do not even count children as clients. Early childhood providers tend to engage families less likely to need complicated supports and more likely to participate and pay regularly and neatly meet eligibility criteria based on such predictability. Thus young children experiencing homelessness have been systematically shut out of services and supports available to more stable and resourced families, and these children continue to fall further behind as the bar for requisite developmental mastery by kindergarten entry continues to rise.

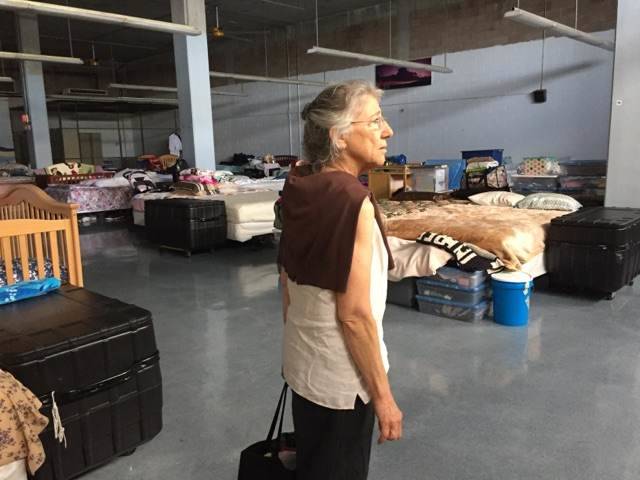

Author Grace Whitney as she toured a family shelter in Honolulu, Hawaii. Large shelters like this one offer little in the way of family privacy, individuality, or boundaries. Many shelters are still closed during daytime hours, sending families out of the building, often with no place to go. Photo courtesy of Grace Whitney

The articles in this edition of the ZERO TO THREE Journal provide a valuable opportunity to focus on the unique issues facing infants, toddlers, and their families experiencing homelessness, and to advocate for respectful collaboration across systems. Adult-centric systems often do not accommodate babies, or the relationships adults have with their babies, nor tailor their efforts to babies’ needs. Moreover, infant–toddler providers are distanced from conversations about policy and best practice, and they may be seen as competitors for scarce resources rather than partners in creating relevant solutions. Infants and their caregiving continue to be marginalized for a host of reasons, therefore the voices in this issue of the Journal are all the more important to share. Bringing diverse systems together, or it could be called “sharing the sandbox,” can be tough! For that reason, the assembled articles provide a range of perspectives and of possibilities for consideration.

Homelessness is not an isolated nor simple issue. Families experiencing homelessness often experience life circumstances that include a cluster of serious challenges and so housing solutions are neither tidy nor universal. One size does not fit all, and typically families need a comprehensive array of resources, supports, benefits, and services that can be individualized to the specific needs of each family member. It is always more than just housing. The articles in this issue of the Journal provide an array of examples that can serve as models of what has been done in new ways. You are encouraged to take these ideas, grow them to meet your own community needs, change public policies, and modify current approaches to better support children and families by always taking their housing circumstances into account.

The Journal issue begins with an article that reviews the major potential sources of data on the number of infants and toddlers experiencing homelessness. Sara Shaw (this issue, p. 11) highlights some of the challenges to using available data because of the lack of a uniform definition of homelessness, a lack of adequate systems to collect data, and even confusion over definitions used by those who must collect and use data for reporting and compliance. She suggests ways to enhance data collection and data sharing to better understand what homelessness actually looks like for infants, toddlers, and their families in their communities, and how to better understand what may work in addressing their particular needs.

Livia Ondi and her colleagues (this issue, p. 21) provide a description of their efforts to reach into the housing world using their model of early childhood mental health consultation services in emergency shelters. This article includes a description of the development, implementation, and evaluation of a decade-long early childhood mental health consultation project at the University of California, San Francisco Infant-Parent Program that provides trauma- and equity-focused prevention, early intervention, and treatment supports to infants, young children, families, and staff in various shelter settings. Using a strong infant mental health approach, the authors share the unique characteristics of the consultant’s role, stance, and practices developed in response to the need for mitigating the impact of trauma related to homelessness in young children within the context of their relationship with caregivers and shelter providers. The authors’ sensitive attention to trauma experienced by parents and children, to the trauma experienced vicariously by staff, and the nuance of relationships to create healing is especially noteworthy.

Rebecca Cuevas and her colleague (this issue, p. 29) also report on a direct service context but one that results from two sectors reaching out to and into one another and the intentional alignment of systems. In this article, which describes an Early Head Start Home Visiting partnership with a local residential recovery program for women and their children, they connect homelessness with the recovery process and with the critical importance of creating sufficient space for promoting healthy parent–child relationships, child development, and recovery for women who are in residential treatment with their young children because they have no home. Instead of completing the recovery process only to go on to an emergency shelter to qualify for housing assistance, this article describes how multiple challenges are successfully addressed by working together on an ongoing basis from the time of entry into recovery to support families in a comprehensive manner.

Next, the article by Janette Herbers and Ilene Henderson (this issue, p. 35) includes a description of the development, implementation, and evaluation of curricula specifically designed for families in emergency and domestic violence shelters; describes the benefits and challenges of promoting parenting supports in unstable settings; and outlines the importance of tailoring curricula to address the complexities introduced by instability and the crisis nature of shelter settings. Again, although there may be a range of resources in communities to support families and provide parenting information and education, available resources may not be tailored to take into account the stress of the emergency shelter experience, the high mobility of families, and the shelter environment itself. This article provides the opportunity to explore what accommodations might be critical in engaging families and creating successful interventions not only in parenting supports but in services for this population more broadly.

J. J. Cutuli and Joe Willard (this issue, p. 43) describe their years-long experience in knitting housing and early childhood systems together in the City of Philadelphia in their article on the BELL project. This piece includes a description of the scope and growth of this extraordinary collaboration led by Peoples Emergency Center, a housing provider operating 18 shelters and engaging health, early childhood, early intervention, philanthropy, research, and advocacy partners to ensure housing services are childproofed and family-friendly and that children are enrolled into early childhood services and programs. Philadelphia has a rich history in connecting housing and early childhood, going back to a unique data collection effort which combined government data across several state and city agencies to reveal that homelessness during infancy was related to later child welfare involvement and school failure. With remarkable champions and partnership, this collaborative approach has sustained and grown to change public policy and professional practice in meaningful ways for the benefit of young children and families. Although there may be publications that list myriad ways of systems working together, the BELL project is an example of how many of those strategies can be implemented in one large community and what the results can be when many systems work together.

And moving on to what potential may lie ahead, Richard Sheward and his colleagues (this issue, p. 52) describe their use of a tool that helps pediatricians assess housing risk. This article includes results of using their three-question housing assessment in pediatric clinics and during emergency exams to better understand the risks homelessness creates for child health and wellness. They share their experience of implementing their assessment strategy in the clinic setting and discuss implications for pediatric policy and practice more broadly. This article is especially instructive and further introduces an important area of emerging practice because it is rare that family housing situations are assessed, and it is even less likely that a strategy or standardized tool is used. Their description of how implementation at the Boston Medical Center resulted in the establishment of new networks to support families is helpful and instructive. In a recent early childhood pilot, researchers used the Quick Risks and Assets for Family Triage–Early Childhood tool (Kull & Farrell, 2018) to assess nearly 1,000 families entering an Early Head Start/Head Start program at the beginning of the program year. This assessment resulted not only in the identification of families at greatest risk and a focus of resources on those families identified, but it also provided a guide for staff on how to assess housing risk. It also opened up the discussion between family service staff and families so that ongoing discussions about safe and stable housing could take place. Sheward and his colleagues provide important validation for embedding housing risk assessment into pediatric practice, early childhood services, and all settings where homelessness must be better identified, addressed, and even prevented.

The final article, by Melissa Kull and her colleagues (this issue, p. 60), focuses on another emerging topic: pregnant and parenting youth. They summarize a Chapin Hall study (Morton, Dworsky, & Samuels, 2017) which revealed the prevalence of homeless youth who are pregnant and/or parenting, and they offer a critical review of the literature spanning several sectors that can serve as the foundation for future policy and practice. This team was unable to select a program that might illustrate best practice, which is not a surprise. Youth and early childhood policies and service sectors remain staunchly separate, and the Chapin Hall study was finally able to provide sound research data on how critical it is for these two sectors to begin to work together. The study of child development covers a span of many years from birth to young adulthood. While youth development programs may have expertise in developmental interventions because of their experience with pregnant and parenting youth, they may lack expertise and access to resources for infant development and parenting. And early childhood programs may not factor aspects of youth development into their supports for parents. Early Head Start does not even collect data on the age of parents it serves. Kull and colleagues discuss these points and it can be hoped that their work will encourage adolescent and early childhood fields to work more closely together to support a truly two-generational approach. Certainly, multiple systems and service sectors could delve more deeply into the unique complexities discussed in this piece and work to align efforts as they involve homelessness in particular.

In addition to what is in this journal edition, there remain additional queries to be integrated into the discussion to be truly comprehensive. For example, fathers play a unique role in the lives of children and families, and housing and early childhood services must accommodate their needs. Some housing programs continue to separate fathers from their families in emergency shelters, and male youth who become parents may be rejected and forced to leave home, too. It is also important to address the child welfare system as it is clear that the lack of safe and stable housing is too often a cause for removal, and youth exiting foster care are at greater risk of homelessness, especially when they are parenting. Data available on housing and child welfare does not yet separate infants and toddlers from other age groups nor are various categories of maltreatment separated out by age, so it is difficult to understand how neglect, abuse, poverty, housing, and other adversity may interact to result in removal or determine choices for interventions. For infants and toddlers specifically, it is unclear whether interventions included partnering with early childhood programs, for instance home visiting services through Early Head Start or Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (Fowler, 2017). Although there have been demonstration projects involving family reunification and access to housing vouchers, one of which contributed to the development of the Quick Risks and Assets for Family Triage tool (Farrell, Dibble, Randall, & Britner, 2017) mentioned earlier, again, child age was not a factor in reporting collective results. The interplay of poverty, diversity, and implicit bias with homelessness for infants and toddlers and their families has yet to be fully understood. Researchers also have not explored the role of homelessness in court team projects and other projects for infants and toddlers and their families. In summary, there is much work to do.

Fathers play a unique role in the lives of children and families, and housing and early childhood services must accommodate their needs. Photo: New Africa/shutterstock

We hope that this collection of articles will be just the beginning of a greater focus and wider discussion of homelessness and infants, toddlers, and their families, and that, as a result, national policy and professional practice will continue to align and reflect a growing sensitivity to this issue through increased resources, specific regulations, research, and additional best practices. Certainly a start would be acknowledging varying definitions of homelessness and ensuring this misalignment is openly addressed in any data collection, analysis, and reporting in the future. In addition, reforming public policy, for example the Homeless Children and Youth Act, in Congress and similar legislation in the states will help to align systems not only for data purposes but for increasing access to available supports and improving collaboration across programs through the creation of more informed regulations, systems, research, and direct services. Examples of policies and practices that would enhance supports for infants, toddlers, and their families experiencing homelessness are discussed by the authors, and the challenge is now to take the articles in this journal, use the resources referenced to refine current practice, truly prioritize homeless populations for service access, and bring to scale the supports proven to be successful. It is hoped that this volume will create the enthusiasm and partnership needed to make that happen.

Authors

Grace Whitney, PhD, MPA, IMH-IV, joined SchoolHouse Connection after 20 years as director of Connecticut’s Head Start State Collaboration Office. She is a developmental psychologist and endorsed as an Infant Mental Health Policy Mentor. Dr. Whitney began her career as a preschool teacher in special education and as a home visitor for at-risk families of infants and toddlers and has since held clinical and administrative positions in early childhood, community mental health, and human services, and has served on aid teams abroad. She has taught full time and as an adjunct instructor in child development/developmental psychology, statistics, and public policy, and she has published on topics related to her work. Throughout her career, she has participated on local, regional, and national boards and has presented often at conferences and professional meetings including ZERO TO THREE, National Head Start Association, and World Congress for Infant Mental Health. She has designed government tools and publications, including three informational modules and related core knowledge and competencies for consultants to programs serving infants and toddlers, the original Early Childhood Self-Assessment Tool for Family Shelters and, most recently, the new interactive learning series Supporting Children and Families Experiencing Homelessness.

Over the 45 years of her career, Dr. Whitney has worked in a variety of contexts involving children without homes, including child welfare, community mental health, and early childhood systems and in orphanages abroad. While a graduate student she was a residential counselor with Second Mile for Runaways and helped start the National Runaway Switchboard. Her master’s thesis focused on federal policy related to runaway youth at the time of passage of the Runaway Youth Act of 1974 which changed running away from a delinquent to a status offense. Dr. Whitney holds a bachelor’s degree in child development/education and a doctorate in family studies from the University of Connecticut, a master’s degree in human development from the Institute for Child Study at the University of Maryland, and a master’s in public administration from Florida Atlantic University.

Marsha Basloe, MS, is president of Child Care Services Association (CCSA), a nationally recognized nonprofit working to ensure affordable, accessible, high-quality early care and education for all children and families. The organization accomplishes its mission through direct services, research, and advocacy. CCSA provides free referral services to families seeking child care, technical assistance to child care businesses, and educational scholarships and salary supplements to child care professionals through the T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® and Child Care WAGE$® Programs. Through the T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood National Center, CCSA licenses its successful programs to states across the country and provides consultation to others addressing child care concerns.

Marsha was senior advisor for the Office of Early Childhood Development at the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for 5 years where she was responsible for coordinating early childhood homelessness working closely with the Office of Head Start, the Office of Child Care, and the Interagency Workgroup on Family Homelessness. Her efforts resulted in multiple self-assessment tools on homelessness, 50 state profiles, and a Congressional briefing to raise the awareness of early childhood homelessness. She also worked on early childhood workforce initiatives, communications from the Office of Early Childhood, and interagency efforts and other initiatives aimed at young children and families.

Suggested Citation

Whitney, G., & Basloe, M. (2019). An introduction to young children and families experiencing homelessness. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 5–9.

References

Cuevas, R., & Whitney, G. (2019). Better together: An Early Head Start partnership supporting families in recovery experiencing homelessness. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 29–34.

Cutuli, J. J., & Willard, J. (2019). Building Early Links for Learning: Connections to promote resilience for young children in family homeless shelters. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 43–50.

Farrell, A. F., Dibble, K. E., Randall, K. G., & Britner, P. A. (2017). Screening for housing instability and homelessness among families undergoing child maltreatment investigation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(1–2), 25–32.

Fowler, P. J. (2017). U.S. commentary: Implications from the Family Options Study for homeless and child welfare services. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, 19(3), 255–264.

Herbers, J. E., & Henderson, I. (2019). My Baby’s First Teacher: Supporting parent–infant relationships in family shelters. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 35–41.

Kull, M. A., Dworsky, A., Horwitz, B., & Farrell, A. F. (2019). Developmental consequences of homelessness for young parents and their children. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 60–66.

Kull, M., & Farrell, A. (2018, November). Screening for housing instability and homelessness in early childhood settings: Associations with family risks and referrals. Poster session presented at the Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Fall Research Conference, Washington, DC.

Morton, M. H., Dworsky, A., & Samuels, G. M. (2017). Missed opportunities: Youth homelessness in America. National estimates. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

Ondi, L., Reinsberg, K., Taranta, A., Jaiswal, A., Scott, A., & Johnston, K. (2019). Early childhood mental health consultation in homeless shelters: Qualities of a trauma-informed consultation practice. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 21–28.

Shaw, S. (2019). Current data on infants and toddlers experiencing homelessness. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 11–19.

Sheward, R., Bovell-Ammon, A., Ahmad, N., Preer, G., Ettinger de Cuba, S., & Sandel, M. (2019). Promoting caregiver and child health through housing stability screening in clinical settings. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(4), 52–59.