Paula D. Zeanah, University of Louisiana at Lafayette; Jeanne Cartier, University of Louisiana at Lafayette; Steven J. Dick, Modern Metrics Barn, Lafayette, Louisiana; Amy Dickson, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center; Caitlin LaVine, Louisiana Office of Public Health, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Julie Larrieu, Tulane University School of Medicine; Joy D. Osofsky, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center; and Charles H. Zeanah, Tulane University School of Medicine

Abstract

Research demonstrates that adverse experiences early in life can lead to negative health and social outcomes many years later, and these findings have significant implications for infant mental health. In this article, the authors present the results of a statewide, cross-sector survey that examined the awareness and activities regarding adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in Louisiana, a state that regularly ranks among the least healthy of all 50 states. Increased awareness of the effects of ACEs has mobilized efforts across the state, yet significant challenges, especially regarding the early childhood mental health workforce, remain. The authors discuss implications and recommendations for next steps.

Research demonstrates that adverse experiences early in life can lead to negative health and social outcomes many years later, and that exposure to multiple risk factors, as compared with a single adverse experience, more strongly predicts negative developmental outcomes. Perhaps the most influential of these studies is the Kaiser Permanente-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study (Felitti et al., 1998), in which more than 17,000 adult members of the Kaiser Permanente health care system reported on their experiences of abuse, neglect, and exposure to household dysfunction that had occurred before they were 18 years old. The investigators identified 10 different types of ACEs: physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; mother treated violently; household substance abuse; household mental illness; parental separation or divorce; and incarceration of a household member. The most important finding was a “dose-response” relationship between the number of adversities experienced in childhood with a vast array of adult health problems (Felitti et al., 1998). These findings have significant implications for prevention and early intervention for population as well as individual health, especially in settings with high prevalence of adverse experiences.

Because Louisiana’s population in general has more economic and social risks than the study population of the original Kaiser-CDC ACEs study, the relationship between adversity and health outcomes in Louisiana is vital to delineate. Louisiana is the least healthy of all 50 states and ranks 45th in obesity, 46th in cardiovascular and premature deaths, 47th in diabetes and frequent mental distress, and 48th in smoking (America’s Health Rankings, 2018a). Louisiana also ranks 49th for low birthweight and 46th for infant mortality (America’s Health Rankings, 2018b), both of which have been associated with ACEs (Smith et al., 2016).

In fact, Louisiana is ranked 3rd in the US of the highest per capita number of children (birth to 17 years) who have experienced two or more ACEs: 28.2% compared to 21.7% U.S. average (America’s Health Rankings, 2018b). Studies have also demonstrated the proximal effects of exposure to ACEs in young children, including maternal ACEs and young children’s adaptation. For example, mothers’ prenatal reports of their own adverse experiences predict telomere length in placental tissue and across infancy in their children, as well as associations with impaired stress response in children at 4 months and externalizing behavior problems at 18 months (Esteves et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2019).

To address these challenges, the Louisiana ACE Initiative was convened in 2014. Comprising representatives from a variety of child- and family-serving state and nonprofit agencies, advocacy organizations, and academic institutions, the Initiative strives to be a “catalyst for efforts to recognize, prevent, and address the impact of adverse childhood experiences on children and families” (Louisiana ACE Initiative Bylaws, 2016). The ACE Initiative led the development of the Louisiana ACE Educator Program, overseen by the Louisiana Bureau of Family Health. Using the ACE Interface Master Trainer program (ACE Interface, 2014), the Louisiana ACE Educator Program recruits and trains multisector professionals to deliver public health education on ACEs science, the ACE Study, and protective factors. To learn more about the impact of ACE education in Louisiana, a partnership was formed among the ACE Initiative; the Louisiana Early Trauma Task Force, a subgroup of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s Early Trauma Treatment Network; and the University of Louisiana Picard Center/College of Nursing staff and faculty.

ACE Survey Project

The initial project that emerged from the partnership was a survey to assess the saturation of ACE awareness in Louisiana, gaps and needs for ACE education, and trauma-informed prevention and intervention activities. This article describes central findings from the survey and points to remaining challenges, drawn from the formal report (Zeanah et al., 2020).

Participants

Potential participants were identified by project collaborators from the sectors of health and mental health, early childhood education, primary and secondary education, child welfare, juvenile justice, law enforcement, community education and support services, parent education and home visiting programs, child and family advocates, legislators, clergy and religious community, and ACE educators. The identified individuals received an invitation via email to participate in the survey. To augment the initial list, participants were asked to forward the survey to additional qualified potential participants. This type of purposive, “snowball” sampling is not considered to be representative of the target population (Noy, 2008), but it is an acceptable approach when the target population is a small proportion of the overall population (Palinkas et al., 2015). Institutional Review Board approvals were obtained from the involved institutions (University of Louisiana Lafayette, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, Tulane University School of Medicine, and the Louisiana Office of Public Health).

Procedures

An anonymous online survey, inspired by a similar survey conducted by Forstadt and Rains (2011) for the state of Maine (Andrews et al., 2016), was developed to capture ACE-related perspectives and activities across Louisiana (Zeanah et al., 2020). Use of branching strategy ensured obtaining the most information with the fewest questions. First, all respondents were asked if they were knowledgeable about ACEs. If the respondent did not know about ACEs at all, they were directed to the end of the survey to complete questions answered by everyone—demographic, geographic, and attitude items. The second major branch routed participants to specific questions based on service-sector identification. Following the specific questions, all respondents were directed to the general questions at the end of the survey. The average completion time was less than 12 minutes (Zeanah et al., 2020). The survey is available on request from the authors.

Data Analyses and Results

Initial descriptive data from the survey were provided by Survey Monkey with additional data manipulation and visualization using Excel (Microsoft Office365). Details of data collection and analyses are provided in the full report (Zeanah et al., 2020).

Demographic Characteristics

Of the 981 professionals initially responding to the survey, 9 declined to participate, and 44 dropped from the survey before answering the first question, leaving a total of 928 respondents. Respondents represented every region of the state, and the percent of respondents from each region roughly paralleled the percent of Louisiana’s population in each region (Zeanah et al., 2020). Similarly, the race/ethnicity of respondents was similar to that of Louisiana, with 68% of respondents reporting as Caucasian, 28% as African-American, 3% as Hispanic, 1% as Asian, and less than 3% as “other” (Zeanah et al., 2020).

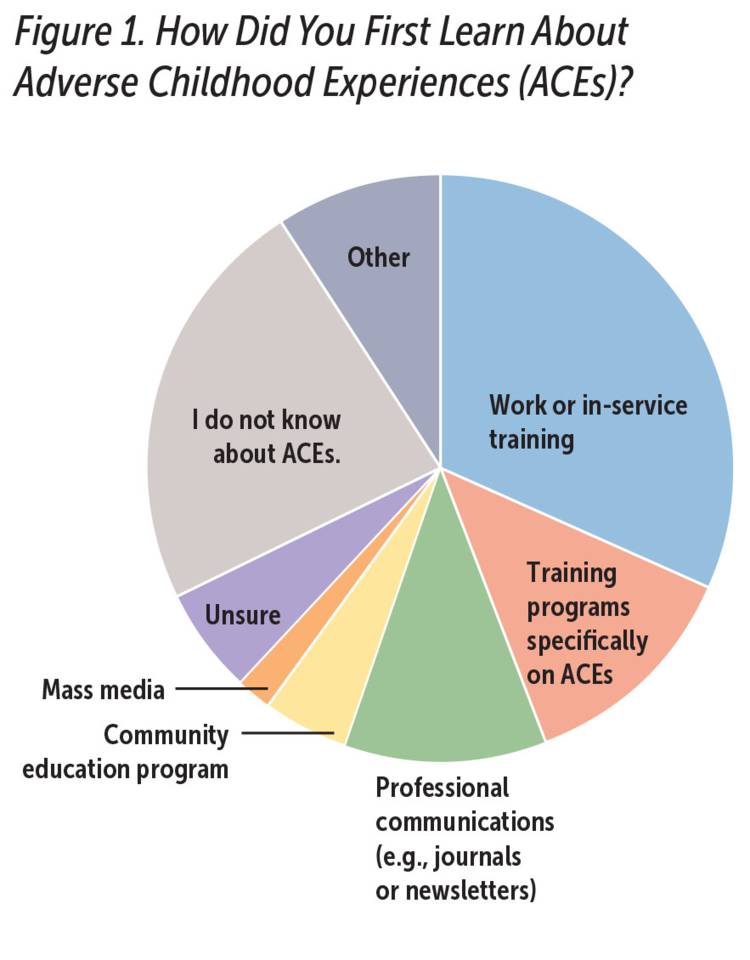

As shown in Figure 1, more than three quarters of participants reported at least some knowledge of ACEs, and respondents had learned about ACEs from a variety of sources. Because the survey focused on experiences of professionals who had at least some knowledge of ACEs, those who indicated they did not know about ACEs at all (n = 215) were excluded from questions regarding ACE knowledge or activities. Notably, only 45% of total respondents (n = 412) indicated they were familiar with the original Kaiser-CDC ACE study. The professionals who responded to the survey served the needs of children and families through the range of clinical, administrative, advocacy, and education roles (Zeanah et al., 2020).

Zeanah et al., 2020, with permission from the authors

Note: N = 924

General Knowledge of ACEs and Impact on Work Activities

The vast majority of respondents felt that ACEs information was important to their work (85.4%), and indicated they believed that the information is useful for the general public (81.1%), but only 14% indicated they had strong knowledge which they regularly applied to their work. Another 31% rated themselves as having a good grasp of the information and were beginning to apply the research, and a majority of respondents reported having introductory knowledge of ACEs or that they were aware of the research findings but did not know how to apply the knowledge.

ACE and Trauma-Informed Prevention and Intervention Activities

Responses are analyzed by service sectors.

Direct Service Providers

Respondents who provided face-to-face services to children and families (e.g., nurses, social workers, physicians, early childhood education providers), or who worked as supervisors, home visitors, and consultants were combined into the category of direct service providers. Examples of services provided included referral (63%); screening (54%); medical observation and interventions, including psychotherapy (48%); training for professionals (31%); and community education (19%).

Direct service providers identified a number of benefits to providing ACE-informed services for children and families, including increased self-awareness/personal improvement (65.3%), increased willingness of clients to obtain needed services or support (48.2%), and improved relationships with other providers or service agencies (40.3%).

Barriers for providers as well as clients included lack of resources and referral options, and lack of knowledge about what to do. Considering client barriers to ACE-related services, providers identified client resistance to change, discomfort when being asked about ACEs, and logistical issues or difficulty accessing services.

Mental Health Providers

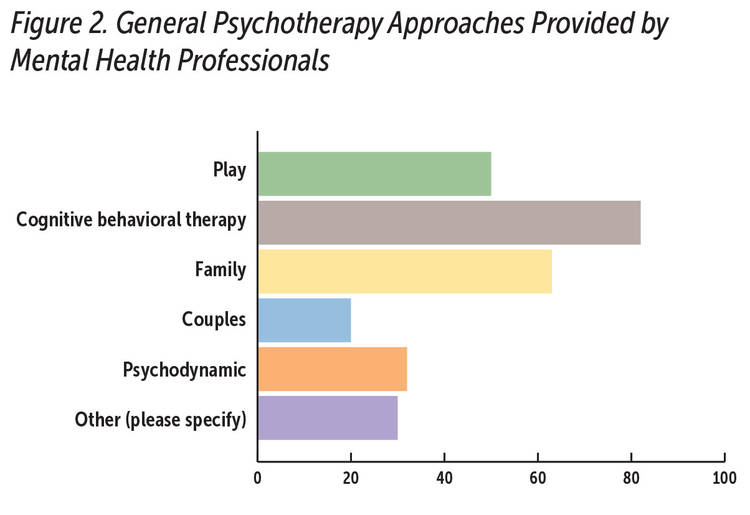

Of the 322 direct service providers who responded to the survey, 305 participants endorsed that they provided some type of mental health services, and 92 identified as mental health professionals who provide trauma-specific care to children and families. As seen in Figure 2, the mental health professionals provided an array of psychotherapy aimed at individuals and families; cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and family therapy were most common.

Source: Zeanah et al., 2020, with permission from the authors.

Note: N = 92

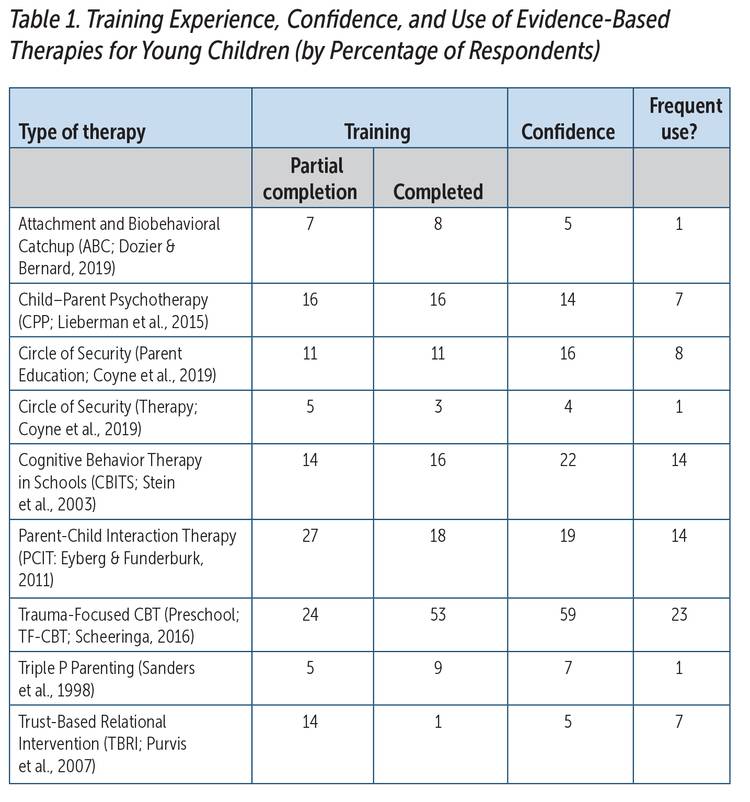

Mental health professionals rated their experiences in providing several trauma-focused, evidence-based therapies (EBTs) aimed at children 6 years and younger (see Table 1). Each of the therapies requires specialized training of varying intensity, and training for most of the listed EBTs is available in Louisiana. Some respondents were trained in more than one EBT.

Source: Zeanah et al., 2020, adapted with permission of the authors.

Note: N = 92

Overall, the respondents’ self-reported skills and experiences with EBTs for young children were limited. The most frequently completed EBT was trauma-focused CBT, but fewer than half of the respondents reported they use that therapy frequently. Notably, more respondents reported feeling confident in providing the therapy than had completed the training, but few who had completed training reported using the therapy frequently.

Finally, mental health professionals identified interventions they found most useful for working with children and families impacted by trauma. These included the identified EBTs, individual and group therapy, art and play therapies, and skill and solution-based approaches, as well as specific therapies including eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, (Shapiro, 2018), the Nurturing Parenting Program (see Maher et al., 2011), short-term psychodynamic therapy, and dialectical behavior therapy (see Behavioral Research & Therapy Clinics, n.d., for an overview). When asked what would help them better serve children, the most frequent responses indicated more training was needed.

Administrators, Program Managers, Agency Directors

Of the 144 administrator respondents, 96% indicated that understanding the effects of ACEs was essential or important. Administrators reported the ACE- and trauma-related services provided by their programs included direct services (87%), advocacy (81%), education for professionals (80%), community education (76%), research or program evaluation (66%), and spiritual support (62%). Administrators also identified benefits to providing ACE-related services and activities, including improved services and outcomes (81%), better staff development (74%), improved relationships with clients (72%), incorporation of more trauma-informed approaches (72%), and improved collaboration with other agencies (65%). Barriers to providing ACE-related services and activities included lack of information about impact of ACEs (58%) and how to respond (51%); implementation and sustainability costs (47%); lack of support for staff, including for training and supervision (43%); and inadequate staff to implement services (38%).

Community Educators, Advocates, and Supporters

Community educators and advocates (n = 92) perceived there could be a number of benefits for communities regarding ACE education, ranging from better recognition of the impact of trauma on community health (74%) and the potential for breaking cycles of violence and illness (71%), to increased support for preventive health efforts (58%) and decreased costs of services (21%).

Perceived community barriers included general lack of knowledge about ACEs (71%), lack of funding and community resources (each at 52%), uncertainty about how to address ACEs at the community level (36%), other issues with higher priority (31%), or lack of fit with community needs or values (23%).

University and Medical School Educators

The sample of university and medical school educators was small (n = 24), however, most (70%) regularly incorporated ACE-related content into their courses, and another 25% indicated they “sometimes” included the content. ACE-related content ranged from a basic introduction of ACEs to preparing students with sufficient knowledge and skills to address ACEs with clients/families, systems, or communities.

Perceived Needs and Priorities for Future Development of ACE Resources and Activities

All service sector respondents were asked their perceptions of the resources and supports to provide trauma and ACE-related services. The findings were not surprising: additional training/education in evidence-based practices (62%), incorporation of trauma-informed approaches or programs (54%), better funding (54%), and partnerships and collaboration with other agencies/professionals (52%) were top priorities. Respondents listed specific education needs such as the impact of ACEs and trauma on neurobiology including the impact on adults, expanding ACE education to incorporate other types of trauma/adversity, assessment procedures and protocols, and more information about community resources. In terms of general resources, more than half of the respondents wanted more educational materials for professionals and families, support for launching and sustaining services, access to community data, and web-based resources for statewide services and activities. Approximately half the respondents ranked trauma-informed approaches in schools, education for professionals, and prevention services as highest priorities. For many respondents, it was difficult to determine priorities, and certainly the need for more and better referral services and resources to address basic needs also were highlighted.

Discussion and Implications

Twenty years after the initial publication from the Kaiser-CDC ACE Study (Felitti et al., 1998), the findings of this survey demonstrate that information about ACEs has reached every region of Louisiana. Across disciplines, respondents perceived ACE education as highly valued, relevant, and beneficial to service recipients, staff, programs, and communities. Nevertheless, slightly more than half of the survey respondents indicated they had only basic, introductory knowledge and/or did not know how to apply the knowledge.

Essential for ACE education efforts is the increasing evidence that beyond the 10 ACEs in the Kaiser-CDC study, other ACEs exist and should be considered. For example, racism (Geronimus, 1992; Paradies et al., 2015), corporal punishment (Afifi et al., 2017; Taylor et al., 2011), neighborhood disorganization (Theall et al., 2013), and exposure to community violence (Osofsky & McAlister Groves, 2018) all show considerable adverse effects. A definite educational priority is to embrace the original ACE Study findings and also to develop a broader appreciation for important adverse experiences beyond the original 10 that were included in that study.

Direct service providers described a wide range of clinical trauma-related services and activities, with screening and referral most frequently endorsed, but many of the identified approaches were not specifically evidence-based to address the impact of trauma. Notably, only a few of the mental health respondents indicated they were fully trained, confident, or actively using specific, trauma-focused, evidence-based therapies for young children. There was consistent recognition of the need for more ACE education for both the public and for professionals throughout the state.

The vast majority of administrators, program managers, and agency directors reported their programs engage in a variety of ACE- and trauma-related services. Similar to direct service providers, administrators believed that ACE-related knowledge has a positive impact on their agency or program activities, but often felt they did not have enough knowledge regarding what to do and/or lacked the resources to implement activities.

In addition, the majority of advocacy and community development professionals indicated that their communities were at least somewhat interested or already had ACE-related activities underway, and they perceived a number of potential benefits to community knowledge of ACEs. However, they too indicated that lack of resources, lack of clarity about what to do, as well as other issues with higher priorities are barriers to more active community uptake of ACE knowledge.

The most-cited barriers to providing ACE education, services, and activities were not surprising: insufficient funding, insufficient referral resources, and insufficient expertise in evidence-based, trauma-informed services. Respondents expressed the need for tools, materials, and strategies for providing education to professionals as well as families and communities. Respondents also identified the need for better awareness of how communities are incorporating ACE-related activities.

The three most frequently endorsed priorities for ACE education and interventions included trauma-informed approaches in schools, education for providers/professionals, and prevention services (e.g., home visiting). Specific trauma-informed approaches were identified as needed in every child-serving system, as was the need to address basics such as housing, food, and health care. Additional priorities included trauma-informed health care services, improved interagency collaboration and communication, and better research on ACEs and trauma in Louisiana.

Benefits of ACE-related information and activities noted by respondents included increased self-awareness and desire for personal improvement, increased client willingness to seek needed services or support, and gaining an increased understanding of the relationship between ACEs and health care (Kalmakis & Chandler, 2015). Program administrators noted improved staff development, improved relationships with clients, and better coordination and collaboration with other agencies. Many community advocates perceived their communities were ready for ACE education and identified a range of possible positive community outcomes, including better recognition of the impact of trauma on community health, the potential for breaking cycles of violence, increased support for preventive health efforts, decreased costs of services, and policy changes.

ACE-related services were perceived to yield better diagnosis and service outcomes, including better child protection outcomes. While results as a whole suggested a broad range of services are available, these approaches are not necessarily evidence-based nor trauma-specific interventions. Nevertheless, the level of skills and experience in mental health clinicians, especially with EBTs aimed at young children, are limited. Fewer than half of the therapists who provided services for young children reported having completed training in specialized EBTs, and few of those who completed the training reported confidence in using these EBTs. Further, many therapists who had received training reported they used the EBTs infrequently. This result is concerning given the efforts in Louisiana to provide training in EBTs to mental health professionals (Phillippi et al., 2020). A priority for future studies is to determine why EBT trainings are not being completed nor being used more frequently. Results suggest that there is lack of infrastructure support within agencies, and/or the professionals need ongoing guidance or supervision that is not provided due to agency time constraints or turnover in professional staff. Perhaps ongoing support/consultation should be added after formal training is completed to help consolidate what has been learned and to provide assistance with real world applications.

Efforts to improve reimbursement for and availability of EBTs are needed; adequate reimbursement is an important barrier to development of adequate numbers of providers and service availability.

Education efforts should expand to target professionals and systems that, based on this survey, may be under-represented. Knowledge of the scope and effects of adversity continues to grow. ACE education must include recent findings including those on importance of screening for ACEs in service and educational settings.

Resources for developing and integrating trauma-informed services in health, educational, and social service settings are growing rapidly (for examples, see Branson et al., 2017; Center on the Developing Child; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019; Child Welfare Information Gateway; National Child Traumatic Stress Network; Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative). Future efforts should focus on identifying community needs, setting community priorities, and identifying and mobilizing community resources. Developing community resilience through built environment, socio-cultural, and economic approaches is emerging as a strategy to address ACEs that complements individually oriented interventions (Pinderhughes et al., 2015).

Incorporating ACE education and research into undergraduate and graduate education, especially for service-oriented disciplines, should be a priority for Louisiana. Not only could such approaches increase the number of professionals ready to address the effects of trauma, research will generate data useful in policy and service-delivery decisions that can help “move the needle” to enhance Louisiana’s health and social outcomes, and have implications for other states (Ahmed & Palermo, 2010).

Parents were identified as a group who may need information about ACEs, may need support in addressing their own ACE experiences to avoid the intergenerational impact of ACEs, and perhaps could be recruited as messengers and educators about ACEs. To date, ACE education in Louisiana has been generated and led by professionals, but including a wider pool of educators could be an effective way of engaging communities. Efforts are just beginning to provide trauma-related education for parents (for examples, see ZERO TO THREE’s resources on trauma and stress, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network’s Center for parent information and resources, and ACEs Connection; Stevens, 2018). However, there are few resources about how to include vulnerable parents as ACE educators. The Self-Healing Communities model (Porter et al., 2016) provides an evidence-based approach to engaging and developing community partners to solve problems and address intergenerational health. In any case, finding ways to communicate with parents, and to incorporate their perspectives and voices into ACE and trauma-related training, is a logical next step.

Another point of emphasis should be strengthening prevention efforts and appreciating the urgency of altering the unhealthy trajectories of children in the earliest years of life. The convergence of research in neuroscience, child development, and economics about the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of early intervention in young children (Knudsen et al., 2006) underscores this urgency. On the other hand, the limited workforce available to address these problems indicates the need to prioritize workforce development.

The survey respondents conveyed a strong, palpable desire for better collaboration and communication about needs, strategies, and resources across systems, service sectors, and communities throughout Louisiana. Currently, many efforts to address ACE prevention and intervention are coming from the communities themselves, most of which is stimulated by the state’s ACE Educator program. Communities have a vested interest in their own well-being yet may not have the knowledge of “what’s available” in terms of evidence-based interventions. Guidance from the state can provide access to numerous resources but may not be cognizant of the unique concerns of a specific community. Therefore, state and local partnerships may provide the most effective approach. In addition, as Porter and colleagues (2016) emphasized, shared and inclusive leadership that respects and recognizes the individual’s expertise and wisdom is essential to develop self-healing communities. The results of this project suggest that there is an appetite for meetings that enable participants to hear and learn about what is happening outside of their own communities. The coordinating and connecting role is not easy but is requisite to assuring growth of evidence-based practices and resources for ACE education, prevention, and intervention.

It is important to note that survey research has a number of limitations that require caution in interpreting outcomes (Fowler, 2013). The study was carried out in a state with a high incidence of poverty and childhood risk. Therefore, the results, while compelling, may not be representative or generalizable to states with different demographics and resources. Further, potential respondents were identified based on knowledge of individuals who were likely to be interested in the topic and thus may not represent fully the population of interest. Our findings may underestimate the activities underway or overestimate the commitment to ACE education and activities. We do not have a true baseline, nor do we have follow-up information to determine rate of growth of ACE-related knowledge and activities.

In conclusion, the proverbial cup is both half-full and half-empty. The good news is that the importance of early adversity is beginning to be appreciated by individuals from a large range of professional disciplines throughout the state. ACE education and activities continue to surge. Currently, more than 150 certified ACE educators have made presentations to more than 15,000 participants. In addition, there are a number of statewide and regional programs focusing on ACEs; the Tulane Early Childhood Policy Leadership Initiative is educating a cadre of leaders who can impact and influence local and state policy affecting young children and their families (Hinshaw-Fuselier et al., 2020). Community efforts are underway in New Orleans (New Orleans Youth and Planning Board, 2020), Baton Rouge (Healthy BR), and Shreveport, among others. Health and social service agencies are embedding evidence-based, trauma-informed practices into services (e.g., the NEAR @home model, Zorrah et al., 2015, for home visiting; the Trust Based Relational Intervention, Purvis et al., 2013, with the Louisiana Department of Children and Family Services). The newly formed Center for Evidence to Practice at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Public Health facilitates access to training in evidence-based practices. But challenges remain, especially regarding efforts to address adversity in young children. Louisiana’s workforce challenges reflect a national problem. A master plan is needed to address how the state as a whole and communities within it can focus meaningful efforts on ensuring that every infant and young child gets quality parenting every day.

Authors

Paula Zeanah, PhD, MSN, RN, is the Lafayette General Medical Center/Our Lady of Lourdes Endowed Chair in Nursing in the College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions and the research director, Picard Center for Child Development, at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. A clinical psychologist and pediatric nurse, Dr. Zeanah’s activities center on the interface of health and mental health, particularly in perinatal, infant, and early childhood mental health, home visiting, and impact of adversity. She currently serves as the chair of Louisiana’s ACE Initiative and chair of the Early Trauma Treatment Taskforce.

Jeanne Cartier, PhD, APRN, PMHNP-BC, is a professor and graduate faculty member in the Department of Nursing in the College of Nursing and Allied Health Professions at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. Dr. Cartier’s scholarly interests focus on examining the relationship between physical and emotional health, especially in vulnerable and underserved populations.

Steven J. Dick, PhD, is an independent statistician and surveyor. He is owner of the Modern Metrics Barn in Lafayette, Louisiana, and an adjunct instructor at Grand Canyon University. Dr. Dick provides research services for commercial, school systems, and charitable organizations. He also publishes research in media management and new media systems.

Julie Larrieu, PhD, a developmental and clinical psychologist, is professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Tulane University School of Medicine. She is the director for the Tulane site of the Early Trauma Treatment Network within the National Child Traumatic Stress Initiative. She is an endorsed International Trainer for child–parent psychotherapy, an evidence-based treatment model for young children and their caregivers who have experienced trauma and loss. Dr. Larrieu’s ongoing clinical and research interests include developmental psychopathology, child abuse and neglect, and symptoms arising from early adversity and trauma.

Caitlin LaVine, LMSW, coordinates the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Educator Program of the Louisiana Department of Health, Bureau of Family Health. Through recruitment and training of professionals and advocates across the state, Ms. LaVine guides statewide efforts to reach a saturation point of ACEs awareness and supports community-led ACEs prevention.

Joy D. Osofsky, PhD, is the Paul J. Ramsay Chair of Psychiatry and Barbara Lemann Professor of Child Welfare at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans where she is also director of the Harris Center for Infant Mental Health Center. Dr. Osofsky has developed intervention programs and published widely on the effects of trauma, including adverse childhood experiences, on children and families and ways to support recovery. She is past president of the World Association for Infant Mental Health and ZERO TO THREE. She played a leadership role in the Gulf Region following Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and currently serves as co-principal investigator for the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Center, Terrorism and Disaster Coalition for Child and Family Resilience.

Charles H. Zeanah, MD, is the Mary Peters Sellars-Polchow Chair in Psychiatry, professor of psychiatry and pediatrics, and vice-chair for child and adolescent psychiatry at the Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans. There, he also directs the Institute of Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health. Throughout his career, Dr. Zeanah has studied the effects of adverse early experiences on development, including trauma, abuse, and neglect. He also has studied interventions designed to enhance recovery following exposure to adverse experiences and published widely on these topics.

Reference

ACE Interface. (2014). The ACE Interface Master Trainer Program

Afifi, T. O., Ford, D., Gershoff, E. T., Merrick, M., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Ports, K. A., MacMillan, L., Holden, G. W., Taylor, C. A., Lee, S. J., & Bennett, R. P. (2017). Spanking and adult mental health impairment: The case for the designation of spanking as an adverse childhood experience. Child Abuse and Neglect, 17, 24–31.

Ahmed, S. M., & Palermo, A. G. S. (2010). Community engagement in research: Framework for education and peer review. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 1380–1387.

America’s Health Rankings. (2018a). Analysis of America’s health rankings composite measure. United Health Foundation.

America’s Health Rankings. (2018b). Health of women and children. United Health Foundation.

Andrews, S. A., Forstadt, L. A., Hood, E., & Rains, M. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences in Maine II: Knowledge, actions and future directions. Maine Resilience Building Network.

Behavioral Research & Therapy Clinics. (n.d.). Dialectical behavioral therapy.

Branson, C. E., Baetz, C. L., Horwitz, S. M., & Hoagwood, K. E. (2017). Trauma-informed juvenile justice systems: A systematic review of definitions and core components. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 9, 635–646.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Infographic: 6 guiding principles to a trauma-informed approach.

Coyne, J., Powell, B., Hoffman,K., Cooper, G., (2019). The Circle of Security. In C. H. Zeanah (Ed.), Handbook of infant mental health (4th ed., pp. 500–513). Guilford Press.

Dozier, M., & Bernard, K. (2019). Coaching parents of vulnerable infants: The attachment and biobehavioral catch-up approach. Guilford Press.

Esteves, K. C., Jones, C. W., Wade, M., Callerame, K., Smith, A. K., Theall, K. P., & Drury, S. S. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences: Implications for offspring telomere length and psychopathology. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 47–57.

Eyberg, S., & Funderburk, B. (2011). Parent Child Interaction Therapy Protocol. PCIT International.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258.

Forstadt, L., & Rains, M. (2011). Working with adverse childhood experiences: Maine’s history, present and future. A report for the Maine Children’s Growth Council.

Fowler Jr., F. J. (2013). Survey research methods (5th ed.). Sage.

Geronimus, A. T. (1992). The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & Disease, 2(3),207–221.

Hinshaw-Fuselier, S., Finelli, J., Usry, L., & Zeanah, C. H. (2020, October). Cultivating early childhood champions: The Tulane early childhood policy leadership institute. ZERO TO THREE Annual Conference.

Jones, C., Esteves, K., Gray, S., Clarke, T., Callerame, K., Theall, K., & Drury, S. (2019). The transgenerational transmission of maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs): Insights from placental aging and infant autonomic nervous system reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 106, 20–27.

Kalmakis, K. A., & Chandler, G. E. (2015). Health consequences of adverse childhood experiences: A systematic review. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27, 457–465.

Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(27), 10555–10162.

Lieberman, A. F., Ghosh Ippen, C., & Van Horn, P. (2015). Don’t hit my mommy! A manual for child—parent psychotherapy with young children exposed to violence and other trauma (2nd ed.). ZERO TO THREE.

Louisiana ACE Initiative. (2016). Louisiana ACE Initiative.

Maher, E. J., Marcynyszyn, L. A., Corwin, T. W., & Hodnett, R. (2011). Dosage matters: The relationship between participation in the Nurturing Parenting Program for Infants, Toddlers, and Preschoolers and subsequent child maltreatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(8), 1426–1434.

National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.). Families and caregivers.

New Orleans Youth and Planning Board. (2020). The possibility of compassionate healing.

Noy, C. (2008). Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 11, 327–344.

Osofsky, J. D., & McAlister Groves, B. (Eds.). (2018). Violence and trauma in the lives of children: Vol I: Understanding the impact Vol II: Prevention and intervention.Praeger.

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation Research. Research, Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42, 533–544.

Paradies, Y., Ben, J., Denson, N., Elias, A., Priest, N., Pieterse, A., Gupta, A., Kelaher, M., & Gee, G. (2015). Racism as a determinant of health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10(9): e0138511.

Phillippi, S., Beiter, K., Thomas, C., & Vos, S. (2020). Identifying gaps and using evidence-based practices to serve the behavioral health needs of Medicaid-insured children. Children and Youth Services Review, 115, 1–8.

Pinderhughes, H., Davis, R., & Williams, M. (2015). Adverse community experiences and resilience: A framework for addressing and preventing community trauma. Prevention Institute.

Porter, L., Martin, K., & Anda, R. (2016). Self-healing communities. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., Dansereau, D. F., & Parris, S. R. (2013). Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI®): A systematic approach to complex developmental trauma. Child & Youth Services, 34, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2013.859906

Purvis, K. B., Cross, D. R., & Sunshine, W. L. (2007). The connected child: Bringing hope and healing to your adoptive family. McGraw-Hill.

Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., & Turner, K. M. T. (1998). Practitioner’s manual for enhanced Triple P. Families International.

Scheeringa, M. (2016). Treating PTSD in preschoolers. Guilford Press.

Shapiro, F. (2018). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy: Principles, protocols, and procedures (3rd ed.), Guilford Press

Smith, M. V., Gotman, N., & Yonkers, K. A. (2016). Early childhood adversity and pregnancy outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 20, 790–798.

Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Kataoka, S. H., Wong, M., Tu, W., Elliott, M. N., et al. (2003). A mental health intervention for schoolchildren exposed to violence: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 290(5), 603–611.

Stevens, J. (2018, November 30). Handouts for parents about understanding ACEs, toxic stress, resilience & parenting with aces. Aces Connection.

Taylor, C. A., Hamvas, L., Rice, J., Newman, D. L., & DeJong, W. (2011). Perceived social norms, expectations, and attitudes toward corporal punishment among an urban community sample of parents. Journal of Urban Health, 88, 254–262.

Theall, K. P., Brett, Z. H., Shirtcliff, E. A., Dunn, E. C., & Drury, S. S. (2013). Neighborhood disorder and telomeres: Connecting children’s exposure to community level stress and cellular response. Social Science & Medicine, 85, 50–58.

Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative. (n.d.). Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Massachusetts Advocates for Children, Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative.

Zeanah, P., Cartier, J., Dick, S., Dickson, A., Larrieu, J., LaVine, C., Osofsky, J., & Zeanah, C. (2020). A view from the field: Awareness, activities, and approaches for addressing adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in Louisiana.

Zorrah, Q., Porter, L., & NEAR@Home Team. (2015). NEAR@Home toolkit. Thrive Washington.