Alissa Rausch and Jaclyn Joseph, University of Denver

Elizabeth Steed, University of Colorado Denver

Abstract

This article explores the ethical obligation of those in the early care and education field to deconstruct ableism (and other–isms, such as racism, sexism, classism) and to reconstruct an understanding of social identity that is strengths-based and affirming. The authors describe the Dis/ability Studies and Critical Race Theory (DisCrit) framework of understanding ableism and provide examples of potential solutions for early childhood providers to explore the role of bias in inclusion practices and deconstruct dis/ability to enact systemic change for young children with dis/abilities and their families.

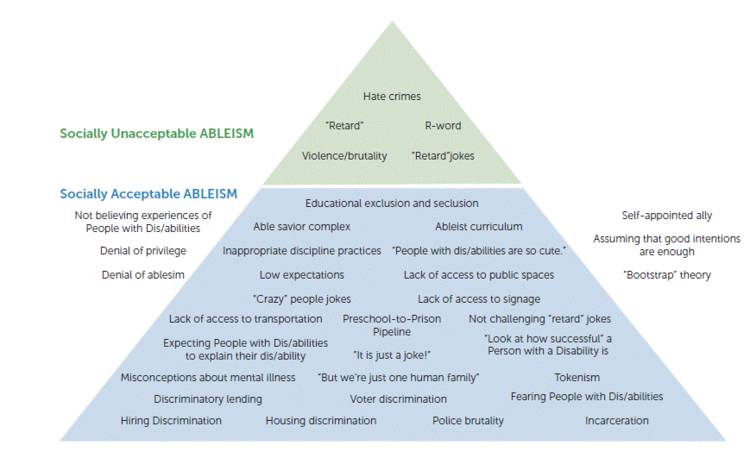

The ethical responsibility to include individuals with dis/abilities across all sectors of society is now enshrined in legislation to protect the rights of individuals with dis/abilities. However, many individuals with dis/abilities remain socially excluded from society in a variety of ways, including exclusion from employment, child-rearing, independent living options, community activities, and from having a social network of friends (Wilson-Kovacs, Ryan, Haslam, & Rabinovich, 2008). The prevention of individuals with dis/abilities from accessing and participating in economic and social aspects of life leads to their alienation and distancing from mainstream society (Green, Davis, Karshmer, Marsh, & Straight, 2005; Kaye, Jans, & Jones, 2011; McLaughlin, Bell, & Stringer, 2004; Mik-Meyer, 2016). These unfortunate realities are featured in the ableist pyramid (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Ableism Pyramid

Very young children with dis/abilities are at risk for social exclusion as evidenced by a lack of visibility in their community (e.g., parks, playgrounds, community recreation centers; Burke, 2012) and in early care and education (ECE) environments (Barton & Smith, 2015). First, community spaces, such as public parks and playgrounds, may include both physical and social barriers to the inclusion of young children with dis/abilities (Ripat & Becker, 2012). Community playgrounds may not be fully accessible to children who use a wheelchair or other mobility device (e.g., barriers around the play area) or they may not include accessible swings or other play structures for children with various dis/abilities. Further, there may be a lack of social support for the agency of children with dis/abilities to play in these spaces and contribute to the learning and social competencies of children without dis/abilities (Burke, 2012). Families of children with dis/abilities may get the explicit or implicit message that their children do not belong in these community spaces in which other children are playing and learning (Prellwitz & Skär, 2007). This kind of social exclusion negatively impacts the child and family system (e.g., access to learning opportunities outside of the home, a social network of friends) in the short and long-term (Montes & Halterman, 2008; Stegelin, 2018).

Second, young children with dis/abilities are not as visible in their community child care settings as they could be due to a lack of inclusive child care options (Applegate, Pentimonti, & Justice, 2011; DeVore & Bowers, 2006; Houser, McCarthy, Lawer, & Mandell, 2014). The majority of mothers of young children work outside of the home (U.S. Department of Labor, 2016), yet less than half of young children with dis/abilities are included in typical ECE settings (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education, 2014). Due to limited available choices, children with dis/abilities are more likely to enter child care at a later age, for fewer hours, and to access informal child care (e.g., staying at home with a relative) rather than formal child care (Booth-LaForce & Kelly, 2004). When family income is added to analyses of family child care options, the results are even more troubling; children with dis/abilities from low-income families are more likely to receive lower quality care than children without dis/abilities from the same income bracket, and families are less likely to be satisfied with their child’s care (Sullivan, Farnsworth, & Susman-Stillman, 2018; Wall, Kisker, Peterson, Carta, & Jeon, 2006). Lastly, young children with dis/abilities who are included in child care through the “front door” are still at risk of being excluded through the “back door” via suspension or expulsion (Novoa & Malik, 2018). Suspensions and expulsions result in discontinuity in care and other problematic outcomes for children with dis/abilities and their families (Meek & Gilliam, 2016).

Young children with dis/abilities’ exclusion from community spaces and ECE settings may be related to various factors, including a lack of resources to provide individualized support, a lack of training for early care administrative and teaching staff around the logistics and benefits of inclusion, and/or persistent negative attitudes and beliefs about dis/ability. A lack of training of community child care administrators and teachers has long been cited as a barrier to the inclusion of young children with dis/abilities (e.g., Warfield & Hauser-Cram, 1996; Weglarz-Ward, Santos, & Timmer, 2019). A lack of training related to supporting children with dis/abilities is associated with more negative attitudes toward inclusion (Knoche, Peterson, Edwards, & Jeon, 2006; Mulvihill, Shearer, & Van Horn, 2002). This situation is especially the case for children with more significant dis/abilities; teachers’ comfort level decreases as the severity of the child’s dis/ability increases (Buysse, Wesley, Keyes, & Bailey, 1996; Stoiber, Gettinger, & Goetz, 1998).

Training is needed to address ECE professionals’ lack of experience and attitudes toward including young children with dis/abilities in their programs (Barton & Smith, 2015; Dinnebeil, McInerney, Fox, & Juchartz-Pendry, 1998; Mulvihill et al., 2004; Yu, 2019). Training efforts for preservice and on-the-job ECE administrators and teachers need both to address effective strategies to include young children with dis/abilities (e.g., embedding, peer-mediated intervention) and to explicitly counter persistent negative attitudes and beliefs about dis/ability (Yu, 2019). This type of comprehensive training approach that both builds skills and addresses implicit and explicit biases about dis/ability may provide the support needed for ECE settings to provide more inclusive services to all children and their families.

This article will describe explicit and implicit biases around ability within systems of ECE, introduce a framework that provides a more affirming way of thinking about dis/ability and other intersecting identities (e.g., race, social class, gender, family structure, language, and immigration and refugee status), and provide concrete solutions for ECE systems to support and serve all young children and their families. Given its dedication to anti-discrimination (National Association for the Education of Young Children [NAEYC], 2009), its welcome of research on implicit bias (NAEYC, 2016), and its established codes of ethics that include a commitment to respecting diversity (NAEYC, 2011), the ECE field is uniquely positioned to work toward reframing dis/ability and to enact solutions that support social inclusion.

Our Stance

Before digging further into a theoretical framework and potential solutions, it is important to have clarity on the specific definitions of words and concepts related to young children with dis/abilities and their intersecting identities. The concepts below are assumed in the theoretical framework and potential solutions:

“Social identities” are based on the current and historical societal construction of power and privilege through which one group of people (e.g., white people, English language speakers, children with no apparent dis/ability) receives power and privilege while another group of people (e.g., People of Color, people who speak Spanish, individuals with nontraditional gender expressions, children with dis/abilities) experiences marginalization and oppression (Colker, 1986, 2009; Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2010).

- The term “all children” refers to young children with each, any, and all child social identities as well as to the various intersections of social identities (Lalvani & Bacon, 2018).

- The inequities young children and families from marginalized populations currently face (e.g., the disproportionate number of Young Boys of Color who are suspended and expelled from their ECE classrooms and programs) are impacted by historical events such as racial segregation and the institutionalization of individuals with dis/abilities (Colker, 1986; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education, 2014).

- The term dis/ability, (spelled with the slash) is used intentionally to counter the word disability (spelled without the slash). The use of the term disability (spelled without the slash) suggests that a person is represented, or identified, by what they cannot do, rather than what they can do.

The DisCrit Framework and ECE

DisCrit is a theoretical framework that draws on the work of Disability Studies and Critical Race Theory (Annama, Connor, & Ferri, 2016a). This framework, heavily influenced by People of Color and people with dis/abilities, considers how the intersection of dis/ability and other marginalized identities can have a compounding, adverse effect on a young child, person, or family (Annamma, Connor, & Ferri, 2013). DisCrit specifically considers the marginalization that Children of Color with dis/abilities and their families experience due to the intersection of power and privilege around race and dis/ability. In the ECE field, the DisCrit framework can be used to understand how a difference in power (e.g., between administrators/teachers/schools and families) can lead to the exclusion of very young children with dis/abilities and other social identities and their families in ECE settings.

Applying the DisCrit framework to improve practices in ECE places emphasis on the perspectives, feelings, and experiences of people from populations that are marginalized and encourages identity-affirming solutions that are grounded in their perspectives (Colker, 1987, 2009). The ways in which Young Children of Color with dis/abilities were, and continue to be, socially isolated and subjected to lower quality ECE are rooted in a history of racial segregation and institutionalization (Colker, 2007, 2013). For example, segregation was historically used to remove Children of Color from general education classrooms, and has therefore created a reality in which Children of Color are disproportionally placed in special education, which can mean that they receive their education and/or related services outside of the least restrictive environment (Colker, 2009; Skiba et al., 2008).

Table 1 applies the DisCrit tenets (e.g., Annamma, Connor, & Ferri, 2016b) to examples describing or explaining specific inequities in ECE. Each example is paired with one of the ethical solutions described in the next section for affirming the individual and complex identities of all children and families and for promoting the social inclusion of all young children, and specifically of young children with dis/abilities and Young Children of Color with dis/abilities.

Ethical Solutions

The tenets of DisCrit lead to various ethical solutions for the ECE field. Solutions grounded in DisCrit focus on reaffirming dis/ability and race at all levels of the ECE system (i.e., provider, program, policy, and research) and on supporting the social inclusion of all young children in their communities. The suggested solutions for resolving ethical challenges that will be the focus of the remainder of this article include: (a) implicit/explicit bias training, (b) authentic family-professional-community partnerships; © dis/ability affirming language and educational approaches; (d) high-quality inclusion that supports community and connections; and (e) policy and accountability systems that reinforce the social inclusion of all young children and their families in their communities.

Table 1. Examples of Dis/ability Critical Race Studies (DisCrit) Factors Applied to Early Childhood Education (ECE)

| Factor | ECE Example | Ethical Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Race and dis/ability are used together to marginalize young children with dis/abilities and young Children of Color with dis/abilities and to further perpetuate what is considered and accepted as “normal” | Young children are offered access to ECE but the quality of services provided within the environments is substandard for some populations of children. | Ensure that all children have access to the services (and providers) that are needed to support their overall development and ability to reach their highest potential.

|

| Young children and families are multidimensional and hold multiple social–cultural identities

Young children and families from marginalized populations experience the material and psychological impact of oppression |

Incorporating rituals or activities in the classroom that are tied to a specific culture or that are not representative of authentic family–community partnerships.

Deficit-based language is used to describe children and families from marginalized populations— “at-risk children”, “disabled children”, “broken families”, etc., and providers are viewed as “experts” on designing supports and determining placements for young children. |

Relationships with families are interactive, reciprocal, and mutually supportive. They are driven by the children, families, and communities and are developed in ways that value the perspectives of families and that promote their ability to make decisions about their children.

Discourse surrounding children with dis/abilities is affirming and centers on how children and families make essential contributions to the community and highlight the value of those contributions. |

| It is important that the voices of young children and families from marginalized populations are heard and represented across research, policy, and practice | Policies are crafted (intentionally or unintentionally) that further institutionalize systems that oppress groups of young children and families (e.g. census-tracked low-income housing communities in concentrated areas). | Practice, policy, and research are inclusive of all children and families and efforts are taken to actively dismantle the underlying systems that oppress marginalized populations. |

| There are legal and historical implications of dis/ability and race that have denied young children and families their rights | Suspension, expulsion, and other inappropriate discipline practices are used disproportionately with Children of Color and children with dis/abilities. | Accountability for inclusion goes beyond the basic implementation of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 2004) with regard to placement decision and it promotes high-quality inclusive practices in all early care and education environments that benefit all young children. |

| Progress experienced by young children with dis/abilities and their families has often occurred due to the “interest convergence of white, middle-class citizens” (p. 11) | Activities depict children without dis/abilities or providers as ameliorating or fixing challenges for children with dis/abilities. Or, children with dis/abilities are depicted as “handi-capable” and are featured as unique or special for “overcoming” challenges to participate in daily life as children without dis/abilities do by doing things such as learning and leading. | Children and families are authentically valued and respected for their contributions in the community and are given opportunities to lead. |

| Activism and resistance are imperative | Providers are frustrated with a culture in ECE that does not provide resources (financial or otherwise) and therefore leave the field. | Providers work with their “boots on the ground” with young children and families and develop the skills and dispositions to engage with policymakers. |

Implicit/Explicit Bias Training

Implicit and explicit bias training works to disrupt the conscious and unconscious belief systems and attitudes held by providers that result in actions and decisions that favor one social identity over another (NAEYC, in press). The ECE field can address implicit/explicit bias in a two-pronged approach that involves supporting adults as well as young children in identifying and countering their implicit and explicit biases. First, and as previously mentioned, it has been shown that rates of disproportional, inappropriate discipline practices are reduced when practitioners receive training on provider bias (Devine, Forscher, Austin, & Cox, 2012; Neitzel, 2018). Similar training for dis/ability biases and for the intersection of bias around varying social identities could also support positive interactions between providers and young children. Implicit/explicit bias training is recommended for all practitioners (e.g., teachers, assistants, transportation staff, food service staff) who interact with Children of Color and with children with dis/abilities. Moreover, this training should be supported by ongoing coaching that encourages continued examination and reflection of provider bias and associated behavior.

Second, research support is growing for the impact of implicit/explicit bias training on the beliefs and behaviors of young children. Qian et al. (2017) found that young children 3 to 5 years old demonstrated lessened implicit and explicit bias through individuation training that depicts children who are different from themselves in a positive light. It is not unreasonable to hope that supporting young children to learn how to construct their own inclusive ideas about dis/ability, race, and other social identities could impact future generations to create systemic social change that responds to the current issues associated with implicit/explicit bias.

Family-Professional-Community Partnerships

There is a widely accepted understanding that a general mitigating factor against unethical ECE practice is the use of family-centered, culturally affirming practice to promote community cohesion and inclusivity (Able, Amsbary, & Zheng, in press; Esteban-Guitart & Moll, 2014). Authentic, family-centered practice considers the community in which the family exists and also accounts for the unique sociocultural identities of each family. Ethically driven ECE environments should be reflective of the families and communities they serve. For example, staff and administration should be representative of the young children and families who attend the program, family- and child-centered materials should be used, and family and culturally affirming pedagogy and practices should be used (Jain, Reno, Cohen, Bassey, & Master, 2019).

Community playgrounds may not be fully accessible to children who use a wheelchair or other mobility device (e.g., barriers around the play area) or they may not include accessible swings or other play structures for children with various dis/abilities. Photo: Shutterstock

When children’s environments are representative of the contexts in which they identify and live, unethical practice and marginalization are mitigated because the home and family system drive educational decision-making as opposed to providers, or “experts” making decisions that take choice and autonomy away from families. When family-centered and culturally affirming practices are central to the ECE environment, the identities of young children and their families are seen beyond binary categories such as “abled” and “disabled.” Such practices promote collective empowerment, which is achieved when very young children and their families, their peers, their peers’ families, their school, and the community in which they live are appreciated for their unique and individual identities. The processes of affirmation and the authentic family-provider-community relationships are fluid and ever-evolving and, therefore, require: (a) time and energy to build healthy relationships, (b) continuous communication in the style and language most preferred by the family, and © decisions driven by the families who are served by the ECE field (Turnbull et al., 2007).

Dis/ability Affirming Language and Approaches

Many ECE standards address the development of social skills by focusing on “accepting others’ differences.” Although acceptance may be an initial step in deconstructing how children from marginalized populations are seen and treated by their communities, it is not enough. It could be argued that it is better to support young children in honoring and affirming (as opposed to accepting) differences in others in a way that acknowledges the unique contributions that only young children with dis/abilities or other various social identities have to offer their communities.

Honoring and affirming the identities of others can be achieved in ECE by using and implementing materials, activities, practices and discourse that eliminate stereotypes about differences. Classroom environments and learning activities should be designed with input from families and with all children in the classroom in mind as opposed to making adaptations or accommodations for children after a “general education” activity is developed. Examples of dis/ability affirming pedagogy include:

- designing an environment with variable seating options for all young children to select from in order that children who require differentiated seating are not seen as unique;

- using co-teaching, consultative, and collaborative models of service provision (transdisciplinary) so that all children receive support from all providers (e.g., lead teachers, assistant teachers, speech pathologists, ECE special educators);

- selecting classroom materials (e.g., books, toys) and designing routines that depict and include children with dis/abilities and varying social identities as capable of contributing equally to the learning community; and

- setting program and classroom norms that are strengths-based and that establish guidelines that affirm individual identities and intersections.

Authentic, family-centered practice considers the community in which the family exists and also accounts for the unique socio-cultural identities of each family. Photo: Shutterstock

High-Quality Inclusion

Although not accepted as universal fact in the ECE field, it is becoming increasingly clear that young children (and especially young children with dis/abilities) should be educated in inclusive settings to optimize all children’s short- and long-term outcomes (Strain, 2017). A main critique DisCrit has for the compulsory placement of young children with dis/abilities in inclusive settings, though, is that such placement decisions rely on the formal equality perspective and can deny families the ability to decide how and where their young children should be educated (Colker, 2009). High-quality inclusion is a superior placement for young children with dis/abilities; however, not all placements comprised of children with and without dis/abililtes meet high-quality inclusion standards. From a DisCrit perspective, the ECE field should increase the number of high-quality inclusive setting options for families of young children with dis/abilities, ensure that families are provided with choices of placements, and value the opinions of families when placement decisions are made (Colker, 1987, 2009).

The implementation of high-quality inclusion is dependent on the ethical commitment of state and local administrations to prioritize the quality of services for all young children (including those with dis/abilities and those with varying social identities). The U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services and Education (2015) provided ethical guidance on this prioritization by defining high-quality inclusion that can and should be generalized to all young children. This article considers inclusion in ECE settings as it relates to programs and to practitioners. Therefore, it refers to: (a) the placement of all young children in high-quality programs and settings; (b) holding high expectations and intentionally promoting (and facilitating through individualized accommodations) young children’s participation in all learning and social activities; and © using evidence-based services and supports to foster the development of young children (across cognitive, language, communication, physical, behavioral, and social–emotional domains), their ability to form reciprocal friendships with peers, and their sense of belonging within the classroom and program.

Furthermore, it is expected that positive child outcomes associated with high-quality inclusion are facilitated by the use and provision of: (a) evidence-based practices that offer specialized and individualized supports across all learning domains; (b) sufficient learning opportunities that include the necessary frequency, intensity, and duration of instruction and that are sufficient across all stages of the learning cycle (i.e., acquisition, fluency, maintenance, and support); and ( c) culturally affirming practices that are driven by the family (Odom et al., 2004). This definition of, and expected practices for, inclusion apply to all young children with dis/abilities, from those with the mildest dis/abilities, to those with the most significant dis/abilities.

Given this definition and these expectations around practice, high-quality inclusion could offer those providing ECE settings an opportunity to deconstruct the deficit-based perceptions often held about dis/ability and other traditionally marginalized populations. When children learn and grow in a community where all young children, regardless of their ability status and/or social-cultural identities receive supports that allow them to thrive and reach their highest potentials, all children as well as the community benefit (Strain & Bovey, 2011). It is not enough to say that the legal requirements of the Individuals With Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA, 2004) ensure that children with dis/abilities and other social identities are valued and affirmed in the ECE community. Rather, bringing this law to life relies on the ethical will of the field to bring the law to life in its implementation. Such ethical practice is central to social change and to the deconstruction of marginalization.

Policy and Accountability Systems

While the suggestions listed in the previous section are recommendations for ECE programs and for the providers in those programs, many of these recommendations also have implications at the policy levels. For example, statesand local administrative units should: (a) reframe common thinking and language around children with dis/abilities and with other social identities; (b) commit to engage in discourse that affirms all children and their families, © develop policies and procedures that define the roles and responsibilities of providers in a collaborative and shared system; and (d) mandate classroom placement options that include high-quality inclusion. Because the deconstruction of dis/ability and marginalization of social identities lies so heavily in ethical decision-making, it is important that it is recognized at the program and provider levels as well as being connected to higher level leadership agendas.

As a specific example of ethical decision-making in policy, the IDEA permits states to have the ability to change the way that children (and particularly young children) who receive specialized and individualized services are labeled and categorized. States are offered the ability to eliminate unnecessary labels for young children that may follow them through the course of their educational career and beyond. Some states have opted to minimally categorize children by dis/ability until age 9, thereby decreasing the stigma for receiving specialized and individualized services. As another example, the culture of educational policy implementation has been one of young children “earning the right” to be part of inclusive settings, when the opposite should be true. State and local officials and providers themselves should encourage policy that assumes that young children start their ECE in the most inclusive settings and are only (if ever) removed from those settings when opt-out criteria has been clearly and stringently defined, applied, and met, and when the family is involved in the placement change decision.

Accountability should also be brought to systems to ensure that ECE programs are equitably accessible for all young children and families and that there is evidence of high-quality placements for all children. Further, some states have prioritized services for children with dis/abilities by embedding dis/ability systems change in professional development systems and in quality rating and improvement systems. Incentives, through increased ratings for the delivery of high-quality inclusive practices, are provided for programs and providers that are better able to serve all young children. To put it simply, higher ratings could be given for programs that conduct implicit/explicit bias training and for those programs that engage in high-quality inclusive practices for all young children and their families.

Some states have opted to minimally categorize children by dis/ability until age 9, thereby decreasing the stigma for receiving specialized and individualized services. Photo: Shutterstock

Conclusion

This article presented a framework of DisCrit for ECE that would affirm the perspectives, feelings, and experiences of people from populations that historically have been marginalized. It also provided several possible solutions that could meet the ethical obligation of the ECE field to support all very young children and their families from a strengths-based and identity-affirming perspective. The solutions that have been offered will require collaborative action to move the field toward meaningful social inclusion for all young children and families, and these solutions will rely on intentional efforts toward anti-subordinating practices and policies. We have demonstrated that standards and legal requirements attempt to address how dis/ability and other traditionally marginalized populations are seen in ECE settings, but these steps are not enough. Rather, in order to promote the likelihood that all very young children and families achieve their highest potentials and feel a true sense of belonging, the field’s ethical standards need to be raised to consider the experiences of all young children and families; how they grow and learn in their environments; and how they are represented, valued, and included in their communities.

Authors

Alissa Rausch, EdD, is an assistant research faculty in the Positive Early Learning Experiences (PELE) Center at the University of Denver. Previously, she has worked as clinical faculty in early childhood education and early childhood special education graduate personnel preparation. Her work in higher education blossomed from 15 years of practice as an early childhood educator working in inclusive preschool classrooms serving young children and their families. Alissa also had the privilege of serving children from diverse backgrounds and their families in their homes and in community settings. Alissa is staff on the National Center for Pyramid Model Innovations and the Early Childhood Technical Assistance Center. Her work centers on technical assistance supporting leaders and practitioners to build their capacity to for high-quality early childhood education and inclusion of children with varying abilities in practice, systems, and advocacy.

Jaclyn Joseph, PhD, BCBA-D, is an assistant research professor at The University of Denver, where she works at the Positive Early Learning Experiences (PELE) Center. Jackie is involved in a number of projects at the PELE Center that include research and technical assistance on the LEAP Model, Pyramid Model, Prevent Teach Reinforce for Young Children, and Prevent Teach Reinforce for Families. Jackie’s professional and researchinterests include young children with challenging behavior and interventions for improving their social and emotional competence. She is also dedicated to promoting and advocating for high-quality inclusive early childhood education opportunities for all young children and especially for her determined, strong, and amazing little girl who has a rare genetic syndrome.

Elizabeth Steed, PhD, an associate professor in the early childhood education program at University of Colorado Denver. Elizabeth has experience working with young children with dis/abilities and their families in classroom and home-based settings. She has been the principal investigator on several research projects focusing on building partnerships with preschool teachers to prevent the development of challenging behavior in young children. She has published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national conferences. Elizabeth is the first author of the Preschool-Wide Evaluation Tool (PreSET; Brookes, 2012), an assessment of program-wide positive behavior interventions and support in early childhood settings.

Suggested Citation

Rausch, A., Joseph, J., & Steed, E. (2019). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit) for inclusion in early childhood education: Ethical considerations of implicit and explicit bias. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(1), 43–51.

References

Able, H., Amsbary, J., & Zheng, S. (in press). Application of DEC family centered practices: Where the rubber meets the road, Division for Early Childhood Monograph: Implementation of Family Centered Practices.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race and Ethnicity and Educationza, 16, 1–31.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D. J., & Ferri, B. A. (2016a). A truncated genealogy of DisCrit. In D. J. Connor, B. A. Ferri, & S. A. Annamma (Eds.), DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education (pp. 1–8). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D. J., & Ferri, B. A. (2016b). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. In D. J. Connor, B. A. Ferri, & S. A. Annamma (Eds.), DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education (pp. 9–32). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Applegate, K. G., Pentimonti, J., & Justice, L. M. (2011). Parents’ selection factors when choosing preschool programs for their children with disabilities. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40, 211–231.

Barton, E. E., & Smith, B. J. (2015). Advancing high-quality preschool inclusion: A discussion and recommendations for the field. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 35, 69–78.

Booth-LaForce, C., & Kelly, J. F. (2004). Childcare patterns and issues for families of preschool children with disabilities. Infants & Young Children, 17, 5–16.

Burke, J. (2012). “Some kids climb up; some kids climb down”: Culturally constructed play-worlds of children with impairments. Disability & Society, 27, 965–981.

Buysse, V., Wesley, P., Keyes, L., & Bailey, D. B., Jr., (1996). Assessing the comfort zone of child care teachers in serving young children with disabilities. Journal of Early Intervention, 20, 189–203.

Colker, R. (1986). Anti-subordination above all: Sex, race, and equal protection. New York University Law Review, p. 1–54.

Colker, R. (1987). The anti-subordination principle: Applications. Wisconsin Women’s Law Journal, 59, 59–80.

Colker, R. (2007). Anti-subordination above all: A disability perspective. Notre Dame Law Review, 82, 1415–1484.

Colker, R. (2009). When is separate unequal? A disability perspective. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Colker, R. (2013). Disabled education: A critical analysis of the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act. New York, NY: NYI Press.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Edwards, J. O. (2010). Anti-bias education for young children and ourselves (2nd ed). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Devine, P. G., Forscher, P. S., Austin, A. J., & Cox, W. T. L. (2012). Long-term reduction in implicit race bias: A prejudice habit-breaking intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 1267–1278.

DeVore, S., & Bowers, B. J. (2006). Childcare for children with disabilities: Families search for specialized care and cooperative childcare partnerships. Infants and Young Children, 19, 203–212.

Dinnebeil, L. A., McInerney, W., Fox, C., & Juchartz-Pendry, K. (1998). An analysis of the perceptions and characteristics of early childhood personnel regarding inclusion in community-based programs: Implications for training and preparation. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 118–128.

Esteban-Guitart, M. & Moll, L.C. (2014). Funds of identity: A new concept based on the Funds of Knowledge approach. Culture & Psychology, 20, 31–48.

Green, S., Davis, C., Karshmer, E., Marsh, P., & Straight, B. (2005). Living stigma: The impact of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in the lives of individuals with disabilities and their families. Sociological Inquiry, 75, 197–215.

Houser, L., McCarthy, M., Lawer, L., & Mandell, D. (2014). A challenging fit: Employment, childcare, and therapeutic support in families of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Social Service Research, 40, 681–698.

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (2004). P. L. 108-446.

Jain, S., Reno, R., Cohen, A. K., Bassey, H., & Master, M. (2019). Building a culturally-responsive, family-driven early childhood system of care: Understanding the needs and strengths of ethnically diverse families of children with social-emotional and behavioral concerns. Children and Youth Services Review, 100, 31–38.

Kaye, H. S., Jans, L. H., & Jones, E. C. (2011). Why don’t employers hire and retain workers with disabilities?. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation, 21, 526–536.

Knoche, L., Peterson, C. A., Edwards, C. P., & Jeon, H. J. (2006). Child care for children with and without disabilities: The provider, observer, and parent perspectives. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 93–109.

Lalvani, P., & Bacon, J. K. (2018). Rethinking “We are all special”: Anti-ableism curricula in early childhood classrooms. Young Exceptional Children. doi:10.1177/1096250618810706.

McLaughlin, M. E., Bell, M. P., & Stringer, D. Y. (2004). Stigma and acceptance of persons with disabilities: Understudied aspects of workforce diversity. Group & Organization Management, 29, 302–333.

Meek, S., & Gilliam, W. (2016). Expulsion and suspension in early education as matters of social justice and health equity. National Academy of Medicine Discussion Paper, 31, 1–12.

Mik-Meyer, N. (2016). Othering, abelism and disability: A discursive analysis of coworkers’ construction of colleagues with visible impairments. Human Relations, 69, 1341–1363.

Montes, G., & Halterman, J. S. (2008). Child care problems and employment among families with preschool-aged children with autism in the United States. Pediatrics, 122, 202–208.

Mulvihill, B. A., Shearer, D., & Van Horn, M. L. (2002). Training, experience, and child care providers’ perceptions of inclusion. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 17(2), 197–215.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). NAEYC’s anti-discrimination position statement—Revised July 2009. Source link.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2011). NAEYC code of ethical conduct and statement of commitment. Source link.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2016). Statement from NAEYC on implicit bias research. Retrieved from source link.

National Association for the Education of Young Children. (in press). Advancing equity in early childhood education: A position statement of the National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Neitzel, J. (2018) Research to practice: Understanding the role of implicit bias in early childhood disciplinary practices, Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 39, 232–242.

Novoa, C., & Malik, R. (2018). Suspensions are not supports: The disciplining of preschoolers with disabilities. Center for American Progress. Source link.

Odom, S. L., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., Hanson, M. J.,…Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the United States: A review of research from an ecological systems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 4, 17–49.

Prellwitz, M., & Skär, L. (2007). Usability of playgrounds for children with different abilities. Occupational Therapy International, 14, 144–155. DOI: 10.1002/oti.230

Qian, M. K, Quinn, P. C., Heyman, G. D., Pascalis, O., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2017). Perceptual individuation training (but not mere exposure) reduces implicit racial bias in preschool children. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 845–859.

Ripat, J., & Becker, P. (2012). Playground usability: What do playground users say? Occupational Therapy International, 19, 144–153.

Skiba, R. J., Simmons, A. B, Shana, R., Gibb, A. C., Rausch, M. K, Cuadrado, J., & Chung, C. (2008). Achieving equity in special education: History, status, and current challenges. Exceptional Children, 74, 264–288.

Stegelin, D. A. (2018). Preschool suspension and expulsion: Defining the issues. Greenville, SC: Institute for Child Success.

Stoiber, K. C., Gettinger, M., & Goetz, D. (1998). Exploring factors influencing parents’ and early childhood practitioners’ beliefs about inclusion. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 13, 107–124.

Strain, P. (2017). Four-year follow-up of children in the LEAP randomized trial: Some planned and accidental findings. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 37, 121–126.

Strain, P. S., & Bovey, E. H. (2011). Randomized, controlled trial of the LEAP model of early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31, 133–154.

Sullivan, A. L., Farnsworth, E. M., & Susman-Stillman, A. (2018). Childcare type and quality among subsidy recipients with and without special needs. Infants and Young Children, 31, 109–127.

Turnbull, A. P., Summers, J. A., Turnbull, R., Brotherson, M. J., Winton, P., Roberts, R., & Stroup-Rentier, V. (2007). Family supports and services in early intervention: A bold vision. Journal of Early Intervention, 29, 187–206.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education(2014). Policy statement on expulsion and suspension policies in early childhood settings. Source link.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Policy statement on inclusion of children with disabilities in early childhood programs. Source link.

U.S. Department of Labor. (2016). Labor force participation rate of women by age, race, and ethnicity. Source link.

Wall, S., Kisker, E. E., Peterson, C. A., Carta, J. J., & Jeon, H. J. (2006). Child care for low-income children with disabilities: Access, quality, and parental satisfaction. Journal of Early Intervention, 28, 283–298.

Warfield, M. E., & Hauser-Cram, P. (1996). Child care needs, arrangements, and satisfaction of mothers of children with developmental disabilities. Mental Retardation, 34, 294–302.

Weglarz-Ward, J. M., Santos, R. M., & Timmer, J. (2019). Factors that support and hinder including infants with disabilities in child care. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47, 163–173.

Wilson-Kovacs, D., Ryan, M. K., Haslam, S. A., & Rabinovich, A. (2008). Just because you can get a wheelchair in the building doesn’t necessarily mean that you can still participate: Barriers to the career advancement of disabled professionals. Disability & Society, 23, 705–717.

Yu, S. (2019). Head Start teachers’ attitudes and perceived competence toward inclusion. Journal of Early Intervention, 41, 30–43.