Jennifer A. Willford, Slippery Rock University

Robert T. Gallen, University of Pittsburgh

Teagan Cruz, Haley Hensler, Mohamad Khalaifa, MiKaila Leonard, Elizabeth Wernert, and Meredith Willard, Slippery Rock University

Abstract

Reflective supervision/consultation (RSC) is a relationship-based form of professional development for the infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) workforce. A critical context for effective RSC is the quality of the reflective alliance between supervisor and supervisee. Their “way of being” together is inclusive of safe, caring, and consistent relationships and serves as a source of resilience for providers. This article describes the impact of a 1-year project in which 49 IECMH supervisors participated virtually in small RSC training groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Supervisors experienced significant improvements in positive emotions and work engagement, with concurrent decreases in ruminative thinking and negative work experiences. Supervisors reported that many factors played a role in their positive experience within RSC training, with the relationships with supervisors and fellow group members as critical to positive outcomes.

Reflective supervision/consultation (RSC) aims to provide infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) providers with experiences that promote learning, maintain fidelity to intervention models, increase the quality of IECMH services, and support provider well-being (Heffron et al., 2016). These outcomes are facilitated within the context of the reflective alliance, which is defined as “the quality of the relationship developing between supervisee and supervisor [which] is of the utmost importance” (Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health, 2018, p. 7). The foundation for reflective practice and learning is the formation of a safe and welcoming space with a trusted mentor (Heffron & Murch, 2010). RSC is different from other types of supervision (e.g., administrative and clinical), because it extends beyond the content of IECMH work to consider how one’s thoughts, feelings, and reactions affect the work and personal experiences of the supervisee (Frosch et al., 2019). The reflective supervisor and supervisee, within the context of the reflective alliance, discuss difficult and sensitive topics while providing care and consideration for both the supervisee and the families for whom they provide care.

Within the context of the reflective alliance the dyad works to build and engage reflective capacity—the ability to understand one’s own and others’ mental states (Parlakian, 2001). Reflective capacity allows for comprehension of the reasoning for an individual’s intentions and perspective-taking by imagining their needs, desires, feelings, beliefs, and goals (Fonagy & Allison, 2012). Engaging reflective capacity includes an effort to reexperience emotional events, evaluating aspects of these events to gain an understanding of the emotions provoked, and using this understanding toward professional and personal growth (Alexander et al., 2012). RSC promotes positive outcomes in IECMH providers, in part, due to the coexamination of one’s thoughts, feelings, actions, and reactions that result from working closely with young children and their families (Eggbeer et al., 2007).

The role of an IECMH provider is inherently difficult and can have a negative effect on provider well-being. For example, the IECMH workforce experiences exposure to stress, adversity, and trauma vicariously through their direct work with at-risk children and families (Paradis et al., 2021). This exposure can be thought of as an “occupational hazard” of IECMH work. Such exposure can place the IECMH workforce at increased risk for vicarious trauma (Sutton et al., 2022), compassion fatigue (Rivera-Kloeppel & Mendenhall, 2021), secondary traumatic stress (Sprang et al., 2021), and burnout (Sprang et al., 2007). (See Table 1.) Shea et al. (2016) reported that frequent and recurrent exposure to child and family trauma can have a cumulative and negative effect on IECMH provider well-being.

Table 1. Potential Risks Encountered by the IECMH Workforce

In addition to the usual difficult nature of this work, the COVID-19 pandemic has the potential to increase these risks within the IECMH workforce (Paradis et al., 2021). Although the effect of the pandemic on IECMH is not fully understood to date, providers experienced many changes, including a reduction in the opportunity to interact directly with families in need, as well as the need to provide services using virtual modalities (e.g., telehealth). Illinois recently reported that the majority (85%) of early intervention providers reported a disruption in meeting with families during COVID-19; the number of sessions delivered and the number of children per caseload decreased significantly. In addition, work limitations during the COVID-19 pandemic led to a reduction in provider confidence: Only 28% of providers reported high confidence with telehealth, as well as a perceived lack of buy-in from caregivers (Roberts et al., 2022). Given the risks to IECMH work, identifying protective factors to promote resilience is important for maintaining fidelity and benefits of IECMH services, reducing turnover in the workforce, reducing stress, and enhancing the well-being of IECMH providers.

Resilience has been defined as the capacity for positive adaptation when exposed to adverse experiences (Masten, 2014; Narayan et al., 2018). Masten (2014) described resilience as “ordinary magic” that stems from personal attributes, context, and supportive relationships. Efforts to identify sources of “ordinary magic” or resilience that counteract or protect against risk are ongoing. For example, Narayan et al. (2018) identified 10 benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) that describe favorable childhood experiences, including the experience of relationships with others reflecting love, predictability, and support. The presence of more BCEs predicted lower posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and fewer stressful life events during pregnancy (Narayan et al., 2018); lower odds of psychological distress in homeless parents (Merrick et al., 2019); and lower depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and less loneliness in college students during the COVID-19 pandemic (Doom et al., 2021). Both Masten’s “ordinary magic” and the research on BCEs highlight the importance of access to interpersonal relationships that are responsive, sensitive, safe, and consistent for promoting resilience. These findings evoke hope for the development and implementation of IECMH systems that create experiences of benevolence, including love, predictability, and support for children, families, and the IECMH workforce (Merrick & Narayan, 2020).

There are parallels between the reflective alliance developed within RSC and the construct of benevolence as resilience. RSC gives IECMH providers the relational experience and practice that increases the quality of care provided to families (Heller et al., 2013). IECMH provider participation in RSC is associated with increased employee satisfaction, improved mental health, and increased quality of care (Frosch et al., 2019). RSC is associated with an increase in job satisfaction as well as a decrease in burnout and secondary traumatic stress (Harker et al., 2016). Bernstein and Edwards (2012, p. 297) described this protective benefit, stating that RSC “helps early childhood practitioners cope with the stress and feelings of being overwhelmed that often result when working with vulnerable families and children.” The present article describes the effect of providing 1 year of RSC by means of a virtual delivery format (V-RSC) to IECMH supervisors during the COVID-19 pandemic. The purpose of this project was to determine whether the experience of participating in V-RSC groups would have a positive effect on IECMH supervisors’ well-being and engagement at work. We were also interested in learning from supervisors what they thought was effective within their RSC group experience.

Although the effect of the pandemic on infant and early childhood mental health is not fully understood to date, providers experienced many changes, including a reduction in the opportunity to interact directly with families in need. Photo: shutterstock/addkm

The RSC Project

In 2020, in a partnership with the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Department of Developmental Disabilities, and Department of Jobs and Family Services, supervisors across infant and early childhood systems— including home visiting, early intervention, and early childhood mental health workforces—participated in 1 year of RSC training. Initially, 49 supervisors participated in a 2-day didactic RSC training experience and were then assigned to one of 10 RSC groups across five RSC mentors (RSC-Ms); the mean RSC group size was 4.8. Group assignments were based on scheduling needs and efforts to avoid participants being placed in RSC groups with their current supervisors or supervisees. IECMH supervisors were assigned to RSC-Ms with whom they worked in monthly 75-minute group sessions across the year.

Five RSC-Ms were recruited for this project on the basis of their expertise and experience as IECMH practitioners and reflective supervisors. The RSC-Ms averaged 52.6 years of age (range = 38–66), were Caucasian, and included three licensed professional counselors, one master of social work/master of education, and one doctor of psychology in clinical psychology. Three of the RSC-Ms hold Infant Mental Health Endorsements at the Mentor Clinical tier, whereas the other two RSC-Ms are recognized regionally as IECMH experts. All RSC-Ms have extensive clinical and supervisory experience, including training in child–parent psychotherapy, averaging 26.4 years of IECMH experience (range = 10–40 years); receiving an average of 10.4 years of RSC themselves; and providing RSC for others, on aver- age, for 9 years (range = 4–20 years). The year-long program provided the state with an opportunity to assess the effectiveness of RSC training on resilience factors in supervisors.

Data Collection and Instruments

An online survey was distributed by email at pre- and post-RSC (1-year) training time points. The survey included demographic questions, quantitative measures, and qualitative questions. Thirty-five training supervisors completed both the pre- and the posttraining surveys. The supervisor training group was 86% female; was 89% Caucasian; and were, on average, 48 years old (range = 30–71). Education levels in the group included 20% with a bachelor’s degree, 74% with a master’s degree, and 6% with a doctoral degree. Seventy-seven percent of the supervisor training group were serving in a supervisory role at the time and had been serving in a supervisory role, on average, for 7.95 years. Supervision was provided in multiple formats, including individual (94%), group (88%), and virtual/online (94%). Fourteen supervisors were lost from the dataset after 1 year of training because of failure to follow instructions to provide unique identifier codes, making it impossible to match pre-to- post responses; because they were no longer working within the IECMH system; or because they failed to respond to the follow-up survey requests. Several questionnaires were included in the survey to assess resilience in practice, including positive emotions, rumination, and positive and negative work experiences. The following measures were included in the survey.

Brief Emotional Experience Scale (six items; BEES-6; Rogers et al., 2016)

The BEES-6 was used to measure positive emotions that were expected to increase. The BEES-6 is a six-item questionnaire that measures emotional well-being and assesses the balance between negative and positive emotions. Three items target positive emotions (happy, calm, and confident), and three items target negative emotions (worried, sad, and afraid). A positive BEES-6 score represents more positive emotion, and a negative BEES score represents more negative emotion. A BEES score of 0 represents a balance between positive and negative emotions.

Reflection–Rumination Questionnaire (24 items; RRQ-24; Trapnell & Campbell, 1999)

The RRQ-24 was used to measure reflection and rumination. The RRQ-24 measures the ability of supervisors to self-reflect about their lives (reflection) and the tendency to have repetitive thoughts about the past (rumination). It was expected that rumination would decrease and reflection would increase.

Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (nine items; UWES-9; Rosenthal, 2014)

The UWES-9 was used to measure positive work engagement, which was expected to increase. The UWES-9 measures the extent to which someone feels immersed in their work. Three subscales were assessed: Vigor, Dedication, and Absorption (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003). The Vigor subscale measures one’s levels of energy, resilience, persistence, and willingness to invest effort. The Dedication subscale measures enthusiasm, pride in one’s work, feeling inspired and challenged, and effort to find significance. The Absorption subscale measures immersion in one’s work and difficulty leaving one’s work. The overall score reflects the level of engagement an individual has regarding their work. A higher score on the UWES-9 suggests higher engagement in work.

After 1 year of reflective supervision/consultation, supervisors also reported spending less time focusing on their problems or distress, they became more active in solving their problems, or both. Photo: shutterstock/fizkes

Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (16 items; OBI-16; Demerouti et al., 2001)

The OBI-16 measured negative effects of work that were expected to decrease. The OBI-16 measures severity of job burnout. Burnout is described as emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and gradual loss of concern about one’s work— attitudes that are caused by work (Demerouti et al., 2003). Two subscales were also assessed: Disengagement and Exhaustion. The Disengagement subscale measures negative attitudes about work and how much an individual attempts to distance themselves from their work. The Exhaustion subscale measures the consequences of intense physical, emotional, and cognitive strain. An overall high score on the OBI-16 suggests high levels of burnout.

Does RSC Training for Early Childhood Program Supervisors Lead to Increased Work-Related Well-Being?

On the BEES-6, supervisors reported more positive emotions overall (e.g., happy, calm, and confident) after 1 year of RSC, and less overall negative emotions (e.g., sad, worried, and afraid; see Table 2, “Well-being”). The BEES-6 has been supported as a measure for monitoring well-being over time, with higher BEES-6 scores associated with lower ratings on measures of anxiety, depression, and stress (Rogers et al., 2021). Indications of positive emotional experiences were widely reported throughout the qualitative responses provided by supervisors. Examples included the following:

“This work has changed all aspects of my life in positive ways.”

“In reflection, the experience has been extremely positive for me on a personal and professional level.”

“I absolutely loved working with [my supervisor] and our group.”

Table 2. Pre-Post Assessment Scores for Reflective Supervision Training in Supervisors

After 1 year of RSC, supervisors also reported spending less time focusing on their problems or distress, they became more active in solving their problems, or both. A reduction in rumination is associated with less extended and intense negative emotions such as anger and hostility (Bushman et al., 2005) and improved physical health (Brosschot et al., 2006). The RRQ-24 Rumination subscale is also associated with measures of psychological well-being (Harrington & Loffredo, 2010). In contrast, RSC participants reported no change in their reflective capabilities. Examination of mean scores suggested that, at baseline, supervisors were already engaging in a high level of reflection (see Table 2, “Well-being”). After training, supervisors were still reflecting at a high level. Qualitative examples of decreased rumination, expressed as increased action, include the following:

“The project has also motivated me to advocate for [and] explore how reflective supervision can be embedded in our agency’s practices.”

“This experience was a crucial component of my ability to guide and support my team through the stress and strain of working to help children, families, and early childhood professionals through a global pandemic.”

“Having the opportunity to reflect on my work and listen to the reflections of others was beneficial for me.”

Several participants reported that the opportunity to experience and practice RSC as group members themselves was important for their professional growth. Photo: shutterstock/pixelheadphoto digitalskillet

Does RSC Training for Early Childhood Program Supervisors Lead to Increased Work-Related Resilience?

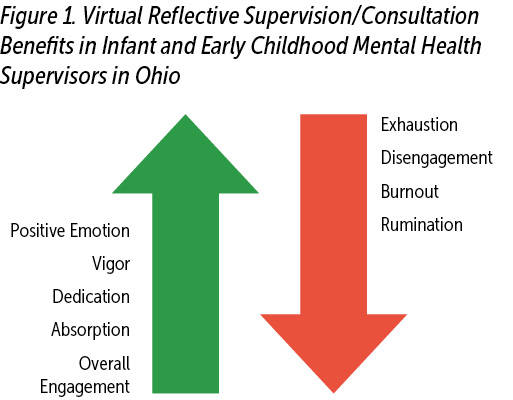

Work-related resilience can be described as “the positive psychological capacity to rebound, to ‘bounce back’ from adversity, uncertainty, conflict, failure, or even positive change, progress, and increased responsibility” (Luthans, 2002, p. 702). Resilience is crucial for promoting competence, the ability to cope with stress, and positive job performance (Cooper et al., 2019; Masten, 2001). RSC training led to an increase in overall work engagement. Supervisors also showed an increase in vigor, described as their willingness to invest energy in work; in dedication, described as enthusiasm for and pride about their work; and in absorption, described as their immersion in work (see Table 2, ”Work-related resilience”). Work engagement is positively associated with intrinsic motivation, psychosomatic health, and high performance among other positive work and personal-related outcomes (Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007). Participant examples of overall increased engagement include the following:

“I am a better employer, team member, mentor, mother and ultimately a servant leader because of this experience.” “The ability to develop and foster such a safe space amongst strangers was energizing.”

“[This was an] … inspirational and motivational experience.”

“Participation felt meaningful and that I was contributing to something on a larger scale.”

Does RSC Training for Early Childhood Program Supervisors Lead to Decreased Negative Work-Related Risks?

Burnout in the workplace includes exhaustion, both physical and emotional; cynicism, described as a negative attitude, frustration, and lack of motivation at work; and reduced efficacy, described as an ability to carry out work tasks confidently (Taylor & Millear, 2016). After 1 year of RSC training, the OBI-16 results showed that supervisors experienced a significant decrease in negative work experiences including significant reductions in exhaustion, disengagement, and burnout (see Table 2, ”Work-related risks”). There were few references to burnout and exhaustion at follow-up, as participants primarily described positive outcomes and support from the RSC experience. Examples included the following:

“Before this process, I felt burdened by the self-imposed expectation that I needed to always provide an answer to supervisee’s questions or challenges. This process has provided me with tools to truly build the capacity of my staff so that they feel confident in their work.”

“… the groups were helpful to support me in my own stressors as a supervisor supporting staff through a pandemic.”

“This experience was a crucial component of my ability to guide and support my team through the stress and strain of working to help children, families, and early childhood professionals through a global pandemic.”

“Participation in this project was an outlet that I did not know I needed… .”

In the quantitative results, we observed an overall theme of resilience in supervisors based on their experiences with RSC. Supervisors experienced positive increases in emotion, less rumination, decreased negative work experiences, and increased engagement in their profession (see Figure 1).

Transitioning from quantitative to qualitative results, we saw specific statements and phrases, directly from the supervisors, describing their reactions, emotions, and perspectives on the effects of engaging in RSC training.

What Did RSC Supervisors Describe as Protective and Significant?

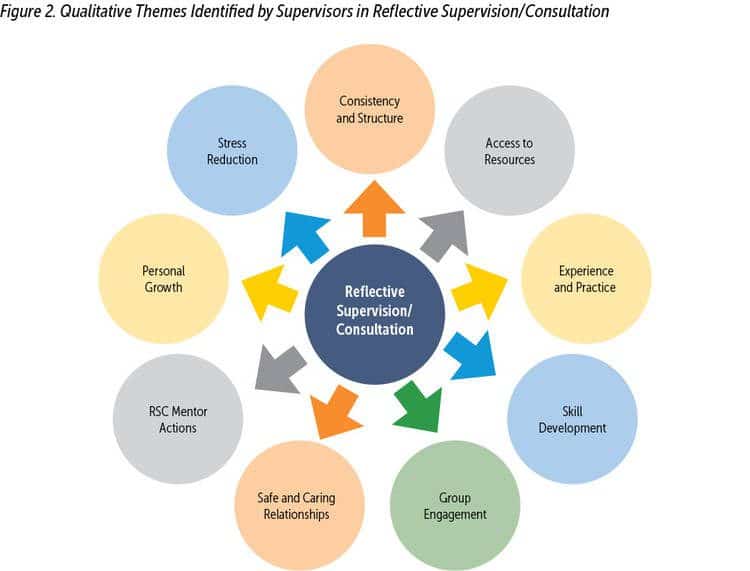

After 1 year of training in RSC, supervisors were asked to respond to open-ended questions about their experience in the RSC project. An informal review of remarks suggested that several previously identified themes and outcomes (Shea et al., 2022; Watson et al., 2016) were readily apparent. All but one (2.8%) participant described this RSC training in highly positive terms. Themes that emerged repeatedly throughout supervisee responses were categorized and labeled on the basis of shared themes (see Figure 2).

Supervisors identified consistency and structure as important components of the RSC experience: “It was nice to have a consistent space to connect and reflect during the pandemic,” and “Having this time set aside each month for my personal growth has been amazing.” Supervisors were provided with RSC textbooks and other supportive material, with some noting that access to resources was effective: “I feel like this experience helped me continue on my journey of being a better reflective supervisor and provided the training and materials to advance my skills.” Several participants reported that the opportunity to experience and practice RSC as group members themselves was important for their professional growth: “Having it modeled for me, being able to receive it, and then practice skills with supervisees and families has progressed my professional development.” Additional comments identified skill development as critical to their RSC experience: “I felt like I grew my skills and overall professional development,” and “I often left the group with notes on how I could improve the group I run.” Others indicated that this learning generalized beyond the workspace: “Not only have I gained skills professionally, but some of the reflective skills that I’ve learned have shaped my interactions with family and friends as well.”

The effect of relationships on outcomes was described by participants across the group and individual RSC-M contexts. The effect of group engagement was remarkable across RSC responses. From expression of “love” for their group members to various statements of “safety,” “support,” and “feeling seen,” it was clear that group engagement, perhaps especially in the midst of a global pandemic, took on special meaning for these supervisors. As one supervisor stated, “I loved having a supportive group of people to talk with through such a challenging year. It was a safe space and a safety net.”

Reflective supervision/consultation practice includes a focus not just on “what to do” but on a “way of being” with others. Photo: shutterstock/Art_Photo

The RSC space itself was described as hosting safe and caring relationships. Participants commented on the “safe reflective space” and the “supportive space” where they could “connect and reflect in deep and meaningful ways.” Relationships were “trusting,” and “feelings were validated and viewed as important by others.” Supervisors felt “respected,” “seen,” and “understood.” Some participants noted the effects of working with RSC-Ms from outside their work space as providing a “neutral” space to “share challenges with my work.” Supervisors identified specific RSC-M actions as critical to their experience. Descriptors included the following: “the calm presence of my facilitator,” and “responses were encouraging and validating”; they experienced “support and nurturance” and appreciated the “focus on regulating, staying present, and pressing into feelings.”

Overall, participants reported personal growth through the RSC training experience. Examples of “learning,” “growth,” and “enhanced” or “increased” reflective capacity were noted across statements. Descriptions of the experience included the following: “It is meaningful because I am learning more about myself through reflection” and “I grew in my reflective skills and in my provision of reflective supervision of my staff.” Finally, supervisors linked the RSC experience to their own resilience over the past year. Several references to stress reduction were included in supervisor responses. The RSC experience was described as “A bright light during COVID” and as “Needed! COVID was hard and isolating. I don’t think I would have been able to provide the support my team needed from me during this last year.” Participants described the RSC as “much needed support” and “transformative and healing.” “It was very beneficial and gave me a place to share struggles, but also a place where I could be supportive to others.”

Virtual-RSC

Supervisors were asked to describe the specific “impact” that engaging in V-RSC groups had on their training experience. Findings in the literature with regard to the effect of the shift to virtual platforms for the implementation of IECMH services are emerging and mixed. For example, Roberts et al. (2022) reported that the shift to telehealth for early interventions had negative effects (noted previously), but they also identified benefits, including increased accessibility of services and increased caregiver involvement. Supervisors in the present RSC project responded with few complaints about the virtual format. Issues with faulty technology, sound quality, and reduced capacity to read body language were stated. In contrast, the overwhelming majority described no consequence of V-RSC, or they described the benefits of the platform. Benefits included easy access to V-RSC relative to traveling to meetings and the time and resources to do so. An additional benefit was the opportunity to work with IECMH providers from across their state, individuals they may not have otherwise met. One respondent identified the less formal nature of the meetings and the ability to see peers in their home spaces as making the process more personal and a better sense of “knowing” one another. Example responses included the following:

“I have been amazed at the way in which our group has been able to transcend being with each other in this space where it is palpable regarding our emotion, feelings of comfort, or uncomfortableness.”

“The way in which we were able to create an emotionally safe space without the full benefit of body language, sensing each other’s energy and the closeness that has been shared by the group despite our [not] being physically together.”

Discussion and Summary

Forty-nine IECMH supervisors in a partnership with the Ohio Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services, Department of Developmental Disabilities, and Department of Jobs and Family Services, embarked on a 1-year journey to train in RSC. This journey just happened to coincide with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the dramatic changes in IECMH service delivery and practices. As such, all aspects of this project were completed virtually, with no in-person meetings between supervisors and the RSC-Ms. Small-group RSC meetings were held virtually (for 75 minutes) once per month, for 12 months, after a 2-day introduction to RSC training. After 1 year, supervisors reported significant positive changes from baseline, including general well-being and positive engagement with work and significant decreases in negative thinking and negative work experiences associated with burnout overall. Specific changes included increased experiences of positive emotional state, and increased positive work engagement, generally with more positive ratings on scales assessing vigor, dedication, and absorption with work. Supervisors reported decreased experiences with ruminative thinking, disengagement with work, exhaustion at work, and overall burnout. These findings add to the growing literature supporting the positive effect of RSC on the IECMH workforce and suggest that this model can be meaningful whether delivered in person or by means of virtual platforms.

The impact of RSC on supervisors appears to have been significant and meaningful. One supervisor, for example, described the experience as “a bright light during COVID.” Across supervisors, the focus of this “bright light” took many forms. Supervisor qualitative responses described essential elements of the experience as including the consistent structure, access to resources, skill development, opportunity for modeling and practice, personal growth, and the important roles of the relationships they formed with their RSC mentor and fellow supervisor group members as critical elements to this experience.

RSC practice includes a focus not just on “what to do” but on a “way of being” with others. Across supervisor comments, there were repeated descriptions of “being with” others in ways that were consistent with those factors identified as protective within resilience research: predictable, supportive, and even loving. In RSC terms, these statements support the establishment of the reflective alliance, the supportive “holding space” created within the RSC experience (Watson et al., 2016). These statements included descriptions of safety, nurturance, being known, being seen, being heard and accepted, warmth, caring, and love. Although a couple of participants expressed a preference for “face-to-face” experiences with others, there was a clear message that these same interpersonal relationship experiences were available through the virtual platform. For some, there was simply no difference; for others, V-RSC had advantages that enhanced the relationship experience and the capacity to “know” one another.

There were limitations to this project. There was no control group of matched supervisors to compare our group with over the year of this project. As such, without random assignment to RSC and “supervision-as-usual” groups, it is possible that the changes identified within our supervisors reflect the effect of some other third variable not assessed here. For example, the move to virtual service provision within the IECMH field during the pandemic may have reduced the level of more direct exposure to the “occupational hazards” of the work, resulting in changes in well-being or emotional status not specific to the RSC experience. With regard to the qualitative data, formal analysis was not completed for this article; thus, assertions made on the basis of these data may be premature. Finally, the use of self-report scales and measures raises concerns about the potential influence of positive response bias producing overly favorable outcomes (Meuwissen & Watson, 2022). Participants formed positive relationships with their RSC-Ms and peer group, perhaps setting up a positive response rate that inflates the overall effect of RSC in this project. These and perhaps other limitations are worthy of consideration and should be addressed in future efforts to measure the effects of RSC and V-RSC. With acknowledgment of these limitations, the results of this project provide additional support to the growing set of studies supporting RSC as a critical form of professional development for the IECMH workforce.

Learn More

- Center for Early Education and Development, University of Minnesota, St. Paul. https://ceed.umn.edu/reflective-practice-center

- A Practical Guide to Reflective Supervision S. Heller & L. Gilkerson (Eds.). (2009) ZERO TO THREE

- How You Are Is as Important as What You Do…in Making a Positive Difference for Infants, Toddlers and Their Families. J. H. Pawl, & M. S. St. John (1998) ZERO TO THREE

- Reflective Supervision: A Guide From Region X to Enhance Reflective Practice Among Home Visiting Programs Region X Collaborative (2018). link

Author Bios

Jennifer A. Willford, PhD, is an associate professor of psychology at Slippery Rock University. She is the program director for neuroscience and preprofessional studies in the department. Her research, for the past 20 years, has focused on the effects of prenatal drug exposure on the development of the brain and cognitive behavior. She teaches courses in research, statistics, clinical neuroscience, and developmental neuroscience.

Robert T. Gallen, PhD, is a licensed clinical psychologist and professor of practice at the University of Pittsburgh, where he coordinates the Master of Science in Applied Developmental Psychology program. He was founding president of the Pennsylvania Association for Infant Mental Health and is a ZERO TO THREE fellow. He teaches courses in infant mental health and developmental psychopathology.

Teagan Cruz is a senior at Slippery Rock University, majoring in psychology with a concentration in neuroscience. She was interested in this project because she understands the risk associated with providing essential infant and early childhood mental health services, and she wants to help to work toward a solution that will reduce the severity of the associated risks. Her plans for the future are to attain a master of science degree in nursing and work as a pediatric nurse practitioner.

Haley Hensler is a psychology major at Slippery Rock University. She is interested in learning about how to improve work–life balance, particularly in infant and early childhood mental health. Her plans are to attend graduate school and further her education in forensics.

Mohamad Khalaifa is an undergraduate student at Slippery Rock University, where he majors in psychology with concentrations in neuroscience and development and minors in statistics and biology. He was interested in this project because he wanted to learn more about reflective supervision and the role it has on burnout. After graduation, Mohamad plans to pursue a doctorate in clinical psychology.

MiKaila Leonard is a psychology major with a neuroscience concentration. While working on this project, she learned about the effects of factors such as burnout and compassion fatigue in individuals who work in infant and early childhood mental health services. She also learned about resiliency factors, such as reflective supervision, that can be used to combat those effects. Her plans are to conduct research in the field of neuroscience.

Elizabeth Wernert is in her last semester at Slippery Rock University, where she is a psychology neuroscience major. She worked on this project as part of her senior Research Capstone and was interested in this project because she is passionate about the early childhood mental health workforce receiving proper support so that they can work to the best of their ability. In the fall of 2022, she is going to begin graduate school at Carlow University for a master’s degree in assessment psychology.

Meredith Willard is a senior at Slippery Rock University, where she is studying psychology with a concentration in development. Her plans are to attend West Virginia University’s Life-Span Development doctoral program. She was recently awarded the Psychology Award for Service and Leadership for her work on the Psychology Student Leadership Committee. She was interested in this project because her research area focuses on adverse childhood experiences and those who work with that population, including the early childhood mental health workforce.

Suggested Citation

Willford, J. A., Gallen, R. T., Cruz, T., Khalaifa, M., Leonard, M., Wernert, E., & Willard, M. (2022). Holding from afar: The protective effect of virtual reflective supervision/consultation during the pandemic. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(4), 62–71.

References

Alexander, L., Gallen, R. T., Salazar, R., & Shamoon-Shanok, R. (2012). Fighting fires with reflective supervision in a state early intervention system: Trading an axe for Mr. Rogers’s slippers. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 32(6), 32–38. Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health. (2018).

Best practice guidelines for reflective supervision/consultation. link

Bernstein, V., & Edwards, R. (2012). Supporting early childhood practitioners through relationship-based, reflective supervision. National Head Start Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for The Early Intervention Field, 15(3), 286–301. link. link

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(2), 113–124. link. link

Bushman, B. J., Bonacci, A. M., Pedersen, W. C., Vasquez, E. A., & Miller, N. (2005). Chewing on it can chew you up: Effects of rumination on triggered displaced aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 969–983. link. link

Choi, G. -Y. (2017). Secondary traumatic stress and empowerment among social workers working with family violence or sexual assault survivors. Journal of Social Work, 17(3), 358–378. link link

Cooper, B., Wang, J., Bartram, T., & Cooke, F. L. (2019). Well-being-oriented human resource management practices and employee performance in the Chinese banking sector: The role of social climate and resilience. Human Resource Management, 58(1), 85–97. link. link

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. link. link

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Vardakou, I., & Kantas, A. (2003). The convergent validity of two burnout instruments: A multitrait-multimethod analysis. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 19(1), 12. link

Doom, J. R., Seok, D., Narayan, A. J., & Fox, K. R. (2021). Adverse and benevolent childhood experiences predict mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adversity and Resilience Science, 2(3), 193–204. link. link

Eggbeer, L., Mann, T. L., & Seibel, N. (2007). Reflective supervision: Past, present and future. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 28(2), 5–9.

Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2012). What is mentalization? The concept and its foundations in developmental research. In N. Midgley & I. Vrouva (Eds.), Minding the child: Mentalization-based interventions with children, young people and their families (pp. 11–34). Routledge.

Frosch, C. A., Mitchell, Y. T., Hardgraves, L., Funk, S. (2019). Stress and coping among early childhood intervention professionals receiving reflective supervision: A qualitative analysis. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(4), 443–458. link. link

Harker, R., Pidgeon, A. M., Klaassen, F., & King, S. (2016). Exploring resilience and mindfulness as preventative factors for psychological distress burnout and secondary traumatic stress among human service professionals. Work: Journal of Prevention, Assessment & Rehabilitation, 54(3), 631–637. link

Harrington, R., & Loffredo, D. A. (2010). Insight, rumination, and self-reflection as predictors of well-being, The Journal of Psychology, 145(1), 39–57. link. link

Heffron, M. C., & Murch, T. (2010). Reflective supervision and leadership in early childhood programs. ZERO TO THREE.

Heffron, M. C., Reynolds, D., & Talbot, B. (2016). Reflecting together: Reflective functioning as a focus for deepening group supervision. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 628–639.

Heller, S. S., Steier, A., Phillips, R., & Eckley, L. (2013). The building blocks for implementing reflective supervision in an early childhood mental health consultation program. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 33(5), 20–27.

Leiter, M. P., Frank, E., & Matheson, T. J. (2009). Demands, values, and burnout: Relevance for physicians. Canadian Family Physician, 55(12), 1224–1225. link

Luthans, F. (2002). The need for and meaning of positive organizational behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(6), 695–706. link. link

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238. link

Masten, A. S. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. Guilford Press. McCann, I. L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131–149. link. link

Merrick, J. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2020). Assessment and screening of positive childhood experiences along with childhood adversity in research, practice, and policy. Journal of Children and Poverty, 26(2), 269–281. link. link

Merrick, J. S., Narayan, A. J., DePasquale, C. E., & Masten, A. S. (2019). Benevolent childhood experiences (BCEs) in homeless parents: A validation and replication study. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(4), 493–498. link. link

Meuwissen, A. S., & Watson, C. (2022). Measuring the depth of reflection in reflective supervision/consultation sessions: Initial validation of the Reflective Interaction Observation Scale (RIOS). Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 256–265. link. link

Narayan, A. J., Rivera, L. M., Bernstein, R. E., Harris, W. W., & Lieberman, A. F. (2018). Positive childhood experiences predict less psychopathology and stress in pregnant women with childhood adversity: A pilot study of the Benevolent Childhood Experiences (BCEs) scale. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78(April), 19–30. link. link

Oginska-Bulik, N., & Michalska, P. (2021). Psychological resilience and secondary traumatic stress in nurses working with terminally ill patients—The mediating role of job burnout. Psychological Services, 18(3), 398–405. link. link

Paradis, N., Johnson, K., & Richardson, Z. (2021). The value of reflective supervision/consultation in early childhood education. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(3), 68–75.

Parlakian, R. (2001). Look, listen, and learn: Reflective supervision and relationship-based work. ZERO TO THREE: Center for Program Excellence. Radey, M., & Figley, C. R. (2007). The social psychology of compassion. Clinical Social Work Journal, 35(3), 207–214. link. link

Rivera-Kloeppel, B., & Mendenhall, T. (2021). Examining the relationship between self-care and compassion fatigue in mental health professionals: A critical review. Traumatology. Advance online publication. link. link

Roberts, M. Y., Thornhill, L., Lee, J., Zellner, M. A., Sudec, L., Grauzer, J., & Stern, Y. S. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on Illinois early intervention services. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(2), 974–981. link. link

Rogers, S. L., Barblett, L., & Robinson, K. (2016). Investigating the impact of NAPLAN on student, parent and teacher emotional distress in independent schools. The Australian Educational Researcher, 43(3), 327–343. linko. link

Rogers, S. L., Cruickshank, T., & Nosaka, K. (2021). Reliability and validity of the Brief Emotional Experience Scale (BEES) for mood monitoring [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. link. link

Rosenthal, J. (2014). Critical synthesis package: Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). MedEdPORTAL. link. link

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale [Unpublished manuscript]. Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

Schaufeli, W., & Salanova, M. (2007). Efficacy or inefficacy, that’s the question: Burnout and work engagement, and their relationships with efficacy beliefs. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 20(2), 177–196. link. link

Shea, S. E., Goldberg, S., & Weatherston, D. J. (2016). A community mental health professional development model for the expansion of reflective practice and supervision: Evaluation of a pilot training series for infant mental health professionals. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(6), 653–669. link. link

Shea, S. E., Sipotz, K., McCormick, A. M., Paradis, N., & Fox, B. (2022). The implementation of a multi-level reflective consultation model in a statewide infant & early childcare education professional development system: Evaluation of a pilot. Infant Mental Health Journal, 43(2), 266–286. link. link

Sprang, G., Clark, J. J., & Whitt-Woosley, A. (2007). Compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout: Factors impacting a professional’s quality of life. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 12(3), 259–280. link. link

Sprang, G., Lei, F., & Bush, H. (2021). Can organizational efforts lead to less secondary traumatic stress? A longitudinal investigation of change. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(4), 443–453. link. link

Sutton, L., Rowe, S., Hammerton, G., & Billings, J. (2022). The contribution of organisational factors to vicarious trauma in mental health professionals: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2022278. link

Taylor, N. Z., & Millear, P. M. R. (2016). The contribution of mindfulness to predicting burnout in the workplace. Personality and Individual Differences, 89(January), 123–128. link. link

Trapnell, P. D., & Campbell, J. D. (1999). Private self-consciousness and the five-factor model of personality: Distinguishing rumination from reflection. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(2). 284–304. link. link

Watson, C., Harrison, M. E., Hennes, J. E., & Harris, M. M. (2016). Revealing “the space between”: Creating an observation scale to understand infant mental health reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 37(2), 14–21.