Abstract

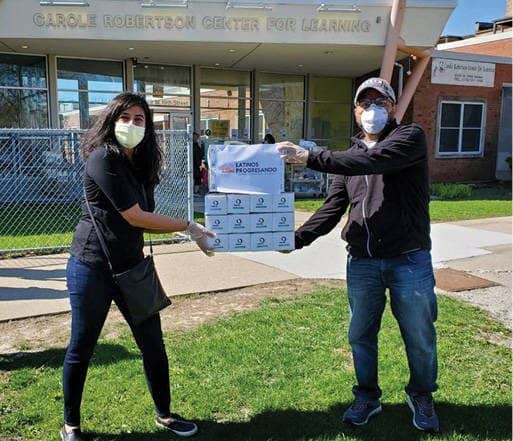

The Carole Robertson Center for Learning is one of the largest early childhood and youth development nonprofit organizations in Chicago, serving more than 1,000 children and their families every day, with a significant presence on the city’s West Side. The organization’s work during the COVID-19 pandemic and a summer grounded in the fight for racial justice was a natural extension of its commitment to being by, for, and with the community that it serves. Although the ways of serving the children, families, and staff were new to all, the organization always stayed true to the ideals of leading and serving with dignity, regardless of the circumstances at play.

Community-based organizations are often regarded as entities that aim to make improvements to a community’s social health, well-being, and overall functioning. These organizations dedicate time, resources, and passion to serving their communities and residing as anchor institutions—places where community members can turn for help in troubling times.

As an organization that was founded on the principle of being by, for, and with the communities that we serve, we at the Carole Robertson Center for Learning take this responsibility seriously. Named after Carole Robertson—one of the four little girls killed by members of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama—we have the honor and responsibility of doing work in Carole’s name and in memory of the four girls. Our name also reflects our commitment to our children and community, and it grounds us in the work we do every day. We are one of the largest early childhood and youth development nonprofit organizations in the city of Chicago, and we have the honor of serving more than 1,000 children and their families in communities that have suffered from a legacy of disinvestment and marginalization. Our families, an even mix of Black and Brown, are often forgotten by the powers that be and are often left without needed resources and services.

Although we have served with a deeply rooted commitment to educate, enrich, and empower families through our comprehensive programming for more than 45 years, we, too, were dumbfounded when COVID-19 knocked on our doors. It was Friday, March 13, 2020; COVID was beginning to take hold of Chicago. Stores were quickly running out of essential goods, and our families and staff members rightfully felt growing concern around their own health and well-being. Nonetheless, we knew that our families needed us. That day, the executive team huddled and made the difficult decision to keep our doors open for at least one more week, despite rumors that Chicago Public Schools would close. This decision was not easy; neither were the many decisions that followed. We knew that we would be taking on the added responsibility of using limited resources to protect our children, families, and the staff, but our team was guided by the principle, “If not us, who?” If we, as an organization by, for, and with the community, left that community in a time of unprecedented need, who would they turn to for support? How do we serve our staff, families, and community with dignity in the middle of a global pandemic? In the weeks and months ahead, these guiding questions called us to action. What followed showcases much of what has often been shared as a response to 2020: distribution of goods to families, rallying staff members to continue to provide essential services, and facilitating town halls to communicate critical information and organizational shifts. However, our story is not about what we did but how we did it.

Honoring Families’ Experiences

What does it mean to deeply serve with dignity?

—Sonja Crum Knight, vice president of programs and impact

The Carole Robertson Center for Learning embedded dignity at every level of our work, beginning first and foremost with our families.Within a week of temporarily closing our doors, we transformed our buildings, once buzzing early childhood classrooms, into central distribution sites for goods and services. We emptied stores of supplies and food and worked to secure additional resources so that every Monday, during our closure, we could host a distribution of these goods. These distributions were significant and provided families with diapers, formula, and food, but they were not unique. What was unique was our approach. Rather than having our families line up outside, we adopted a “come and shop” model to help normalize the experience. Families told the staff the size and quantity they needed for more limited resources such as diapers. While staff members gathered these items, the families were free to browse other items such as books, learning supplies, and canned goods and take as many as they needed. This premise was a simple one: We are not a charity; rather, we exist to serve our families. If a family needs 10 books, they can and should be able to take 10 books.

Staff volunteers during one of our weekly distributions of goods. Photo: Courtesy of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning

These actions may seem small, but they were important. Word spread in the community that our distribution process was both consistent and dignified. Families could count on us because we rallied quickly (we found out later that we were the first nonprofit to open a distribution center in the community) and found creative ways to stock the distribution centers with ample supplies. We were trusted to treat people with respect. One of our lead home visitors, Pilar Gomez, brought this to light best:

Not only were our centers open for distribution, but teachers and support staff volunteered to bring supplies to families who were unable to get to our sites. The moment we closed our doors for programming, staff members called families to learn about their needs and open the doors the very next week to provide for these needs. It became well known what Carole Robertson Center was doing, so much so that when I would call stores to see what they had in stock, they would prioritize working with us, because they knew what we were doing to support families. One of the most rewarding moments came when a group of men who would not normally come to the distribution center showed up the Monday after Chicago made national news for the civil unrest. These men needed diapers and formula for their families but were either turned away from or too afraid to go to stores for fear of being labeled a “rioter.” They had heard about the Center and knew that, even as others were unable or unwilling to open their doors, we would be there.

As the early days of closure turned into weeks, and then months, it became critical to not only ensure that we were supporting the basic needs of families but also find ways to provide academic and cognitive support. During the Monday distribution, books, STEM kits, and learning supplies became a staple. These supply kits, coupled with e-learning, sent the message to families that we see them as whole people, deserving of having their basic needs met and their lives enriched.

Empowering Staff Member’s Voices

We weren’t just told what to do. We were a part of the process.

—Latoya Washington, teacher

An organization cannot meaningfully honor families without lifting up the voices of its workforce. Every night, president and CEO Bela Moté goes to bed asking herself, “Did we do all we could today to do right by our staff, children, and families?” The answer is what grounds her in the mission of the organization. In March 2020, that question would be more important than ever before. The executive team knew that we must continue to serve our families and the community; however, it was important to determine how to do so while recognizing the trauma that staff members were undergoing. To navigate the uncertainty and keep staff members connected, two immediate actions were taken: Weekly town halls were held, and weekly mindfulness sessions were offered to all staff.

One of our teachers sets up a book station at one of our distribution days. Photo: Courtesy of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning

The town halls were launched immediately. The sessions needed to address two important realities: People needed to be heard, and it was going to take all of us to navigate the ever-changing landscape that COVID created. We needed a way to stay connected and communicate with one another, and we also needed a platform where we could problem solve and innovate in real time. The first was easy from a task perspective, but it was challenging to facilitate with a staff of more than 200 individuals. All town halls were conducted via video conference, but we made an intentional decision to utilize the “meeting” function rather than a webinar or presentation mode for these gatherings. Doing so meant that staff members One of our teachers sets up a book station at one of our distribution days. could see one another. It also meant that no one was muted. These seemingly small decision points had a big effect. As one staff member noted, “We were treated equally. We were asked what we thought and what we were comfortable with. And the leadership team listened.”

The second objective was a bit harder to implement. Over the course of 2020, challenges arose that had never been experienced before. For example, how could we open educational services to children safely in the midst of a pandemic? What media should be leveraged to support high-quality educational experiences? How could we reintroduce collecting student documentation during e-learning and with families? These questions demanded collective brainstorming, ongoing idea generation, and rigorous scrutiny for the purpose of always keeping staff, children, and families safe. Committees were formed across our organization to engage all staff members in the process of finding solutions and determining implementation. Then, decisions were shared at the town hall sessions.

Staff members were given the opportunity to engage in committee work; concurrently, we offered sessions to give space for fellowship and the promotion of mental well-being. On a weekly basis, the senior manager of mental health hosted mindfulness sessions. These 30-minute meetings were remarkable for two reasons: They started immediately during the week of the shutdown, and the sessions were notoriously upbeat. As David Walker reflected:

The first few minutes were just people being excited to see one another. The “hellos” lasted a while, and so did the goodbyes. People genuinely missed one another, and this was their time to connect. It was protected and just for them. Some staff members even started to bring their family members. Mostly, it was a time [when] we didn’t have to focus on the world and could focus on ourselves.

President and CEO Bela Moté receiving a donation of face masks from a community partner. Photo: Courtesy of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning

Peace, healing, and reflection circles seemed to become commonplace in the months after the pandemic started. We certainly found space to allow for stress reduction and healing, but we also found ways to focus on the good. An online form was created for people to submit their “silver linings,” which would be shared at the mindfulness session. Despite all the chaos, we found a way to come together as a staff and build our collective resiliency.

Amplifying Servant Leadership

To serve with dignity, we must first lead with dignity.

—Bela Moté, President and CEO

To empower the staff, our executive leadership team knew that they had to embody the ideals of servant leadership—the belief that leaders focus primarily on the growth and well-being of people and the communities to which they belong (Greenleaf, 1973). Recognizing that many of our staff members come from the same communities that we serve, these leaders, of which 80% are women of color, took it upon themselves to work alongside the staff.

The tenets of servant leadership were always embedded in our work, but their importance was highlighted during these tumultuous times. From the onset of the pandemic, our executive leadership took time out of their busy days of reworking and reimagining our organization’s mission to work beside our frontline staff. Our CEO, for example, met with city and state leaders to advocate for continued funding while working with us during our distribution days to put together learning packets and hand out diapers. Through actions like these, our leadership reinforced to the staff how important their work was and that, through thick and thin, the organization’s leaders would be right beside them.

As with our other work during 2020, it was not what we did but how we did it that defined us. As our country confronted its long-standing legacy of systemic racism, the communities we serve were forced to face the trauma caused by historic and existing oppression that they regularly experience. Our staff members, too, were in a place of anguish, as people across the country began to recognize the injustice that they had long felt and communities were transformed into battlegrounds for justice.

As an organization dedicated to empowering BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) communities, we recognized that the role we played in helping our staff and communities makes space for racial healing. After the death of George Floyd, like so many, we decided to facilitate racial healing circles where staff members could come together, share their experiences, and engage in self-reflection in a supportive atmosphere. Naturally, we turned to our senior manager of mental health, who had clinical experience in the mental health and social work realm, to lead these circles and help our staff find peace. However, we quickly recognized that, as a Black man, he, too, needed this space for racial healing and was not in the right headspace to lead his peers in this way. Rather than look to other staff members or outside facilitators, our CEO made the quick decision to host the racial healing session herself. She explained:

I could have gone down the roster of staff members and asked others to facilitate, but I recognized that there wouldn’t be anyone who wasn’t negatively [affected] by George Floyd’s killing. I could have hired someone, but that wouldn’t have been authentic Carole Robertson Center: How could I bring someone in that doesn’t know us and expect the staff to open up about the things they are processing? I knew that if I passed the ball, I wasn’t doing all that I could do as the leader of this organization. What was clear is that we needed to come together and be together, to serve our children and families. I know I can’t solve every pain created by systemic racism and inequity, but what I can make sure to do is not make those same mistakes again and again at the Carole Robertson Center. Essentially, I could listen. So I did.

Vice President of Programs and Impact Sonja Crum Knight works the check-in station after our reopening. Photo: Courtesy of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning

As we reflect on this past year of our organization’s history, these lessons stand out: Even as we find novel ways to serve our communities, staff members, and organizations, we must always embed the principles of dignity and servant leadership. We cannot sacrifice these ideals as we plan innovative ways to serve. They must be a core construct of any and all new models for service if we, as community-based organizations, are to live up to our name and truly make those desired improvements to a community’s social health, well-being, and overall functioning.

Authors

Bela Moté, MEd, president and CEO of the Carole Robertson Center for Learning, is an experienced nonprofit executive and early childhood education professional who has spent her career supporting early childhood and youth development at the local, national, and international levels. She is committed to providing high-quality, deeply effective programs for children, youths, and families. Before being named president and CEO of the Center, Ms. Moté served as vice president of evidence-based youth development for the YMCA of the USA. She has also held leadership positions with the YMCA of Metropolitan Chicago; the Ounce of Prevention Fund; Teaching Strategies, Inc.; and the Robert R. McCormick Foundation. She began her career in early childhood education as a Montessori preschool teacher and considers that experience to be her North Star. She holds a master’s degree in education from Erikson Institute, is a member of the National Association for the Education of Young Children, and participates on many councils and committees. Ms. Moté was a Chicago Foundation for Women’s Breaking Barriers 2011 honoree.

Sonja Crum Knight, PhD, is the vice president of programs and impact at the Carole Robertson Center for Learning. In this role, she leads the programs team in developing systems and processes to elevate quality and deepen the effects of early childhood programming, community partnerships, family engagement, and mental health. She believes that ensuring equitable early learning for our nation’s most vulnerable children is a matter of social justice. With nearly 16 years of service in early childhood education, Dr. Knight has held a variety of roles working both with and for children and their families. Most recently, she was the executive director of early learning and child development at One Hope United. Dr. Knight is a graduate of Capella University, where she earned a doctorate in education. She holds a master’s degree in early childhood administration from National Louis University and postgraduate certification in online instruction from Roosevelt University.

Suggested Citation

Moté, B., & Knight, S. C. (2021). Leading with dignity: One organization’s story of building resiliency through service to others. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(4), 5–9.

Reference

Greenleaf, R. K. (1973). The servant as leader. Greenleaf Center for Servant Leadership.