Rebecca Shlafer, Lauren A. Hindt, and Jennifer B. Saunders

Abstract

A growing body of evidence indicates that mass incarceration has devastating consequences for children, families, and communities. Estimates from the National Survey of Children’s Health indicate that more than 5 million children have had a parent who lived with them go to jail or prison. Yet, most states do not systematically collect information about an incarcerated person’s parenting status. This article describes two studies one about parents in Minnesota prisons and another about parents in Minnesota jails—and the challenges and opportunities that developed from these studies. The authors discuss building community-university-corrections partnerships to collect essential data to inform policy and practice in Minnesota.

The United States is home to 5% of the world’s population, but nearly 25% of the world’s incarcerated people (Walmsley, 2018). A growing body of evidence indicates that mass incarceration has devastating consequences for children, families, and communities (Eddy & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2019). Yet, most states do not systematically collect information about an incarcerated person’s parenting status (Maruschak, Glaze, & Mumola, 2010). Thus, limited information is known about how many people in jails or prisons are parents with minor children (less than 18 years old) or how many children are impacted. In 2007—the most recent year for which national estimates are available—it was estimated that 1.75 million children had a parent currently incarcerated in a state or federal prison (Maruschak et al., 2010). More recent estimates from the National Survey of Children’s Health indicated that more than 5 million children—and 5% of children younger than 6 years old—have had a parent who lived with them go to jail or prison (Murphey & Cooper, 2015).

The distinction between jails and prisons is an important one in terms of the potential impacts on the children and the family system. Jails are locally operated correctional facilities that confine persons before or after adjudication (the judicial decision or sentence). Sentences to jail (typically misdemeanors) are usually 1 year or less, whereas sentences to prison (typically felonies) are generally more than 1 year. Compared to prisons, jails have substantially higher turnover, typically provide fewer programs and services, and often have limited opportunities for contact visitation. These differences have important implications for parents. Thus, knowing how many parents are incarcerated in both jails and prisons is critically important for informing practice and policy.

Not knowing how many parents are incarcerated—or how many children are impacted—is a problem for many reasons. First, not having adequate information about how many parents are in states’ prisons and jails means administrators and policymakers have no way of knowing whether there are enough resources to meet demands. Do facilities offer enough visiting times—and at the right times—to accommodate visits from children and families? Do facilities have enough parenting classes to reach all of the parents who would want to participate? Do facilities have enough staff who are trained to address the unique needs of parents?

More important, though, failing to ask about whether or not someone is a parent often sends a clear message to people who are incarcerated that this part of their identity is not important. The conclusion might be that prisons and jails do not ask about parenting status because they do not care or recognize the importance (see Box 1).

This article describes two studies—one about parents in Minnesota prisons and another about parents in Minnesota jails—and the challenges and opportunities that developed from these two statewide studies.

Parents in Minnesota Prisons

Minnesota has a growing prison population and one of the highest rates of recidivism in the country (Gelb & Denney, 2018; Pew Center on the States, 2011). As a result, thousands of adults are directly impacted by the criminal justice system in Minnesota each year. Like most other states, Minnesota does not systematically collect information about a person’s parenting status when they enter prison (Maruschak et al., 2010), yet this information is critically important for guiding correctional practice and policy. Thus, it was important to have a better sense of the number of adults in Minnesota prisons who were parents with minor children. We knew there were challenges in collecting this basic information.

| Box 1. Being a Father Is Part of Who I Am as a Person. |

|---|

|

I vividly remember a warden approaching me after I had given a presentation about incarcerated parents many years ago. He quietly came up to me after the presentation; it was clear that he was still processing what he had heard. He said, “I have literally never thought about the fact that most of the men in my prisons are also fathers. I’m a father, and when I come into work every day, I try to separate that part of my identity. But the truth is, what happens at home impacts my day at work, and sometimes I bring work home and it impacts my time with my kids. Being a father is part of who I am as a person.” I had this story in mind when I approached Minnesota Department |

There are good reasons why someone in prison might not want to report that they have children, including fear of involvement from child protective services. These fears are understandable, especially considering that increased surveillance among justice-involved families has been shown to contribute to increased rates of children’s out-of-home placements in foster care and racial disparities in incarceration (Edwards, 2016). If we were going to survey people in prison about their parenting status, we needed to take great care in how we were going to ask the right questions. We opted for a brief, anonymous survey. Results from this survey were published in the Prison Journal (Shlafer, Duwe, & Hindt, 2019) and described further in the following sections.

The survey had five basic questions, asking about whether the person was a parent, how many minor children they had, the children’s ages, whether parents lived with their minor children in the month before their arrest, and whether parents were interested in a parenting class. For women, we included a sixth question about whether they were currently pregnant. The survey was administered to all people entering the two Minnesota prisons that handle new admissions during a 6-month period from July 1–December 31, 2014. The 6-month period ensured that we would not resurvey anyone who was released and re-incarcerated. Further, this shorter time period minimized the burden we were placing on the corrections staff who administered the anonymous surveys.

Survey Results

Over the 6 months, a total of 2,521 (86.1% male) people entered the facilities; 2,242 (89% response rate) completed the survey. The majority of respondents (67.5%) were parents with minor children. More women (76.4%) were parents compared to men (66%). Parents had an average of between 2 and 3 children under 18 years old. On the basis of these estimates, approximately 6,626 parents were incarcerated in Minnesota prisons in 2015 (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2015). About 16,069 children—or 1,246 per 100,000 children—had a parent in Minnesota prisons in 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2016). The majority (57.2%) of parents lived with their children in the month before their arrest; more mothers (66.1%) compared to fathers (55.5%) lived with their minor children in the month before their arrests.

Children were an average of 7.46 years old, and most children (65.7%) were 9 years old or younger, as shown in Table 1. The majority (75.3%) of parents of minor children were interested in parenting classes. Mothers, parents with younger children, and parents who lived with their minor children in the month before arrest were more likely to be interested in parenting classes. Of note, 5.6% of the women in prison said that they were currently pregnant. Some women (7.7%) did not report their pregnancy status, presumably because it was unknown at the time of the survey.

Among parents in prison, men were more likely than women to report having at least one young child.

Table 1. Child Ages Reported by Parents Incarcerated in Minnesota Prisons (July–December 2014) and Minnesota Jails (March 2017).

| Child Age | Prison | Jail |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year old | 6.0% | 4.6% |

| 1–4 years old | 26.7% | 26.2% |

| 5–9 years old | 33.0% | 31.5% |

| 10–14 years old | 23.7% | 25.4% |

| 15–17 years old | 10.7% | 12.4% |

Parents of young children (i.e., parents with at least one child from birth to 5 years old) were of particular interest to us given this critical stage for child development. About 60% of parents in prison had at least one child who was 5 years old or younger. Among parents in prison, men were more likely than women to report having at least one young child. About 66% of parents with at least one young child lived with their children prior to arrest. About 81% of parents with at least one young child were interested in taking a parenting class if one were available.

Our estimates of parents and pregnant women in prison were higher than national prison estimates from the Bureau of Justice Statistics (Maruschak, 2008) and state estimates (Lamb & Dorsey, 2014; New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services, 2013), likely due to differences in survey methods. Other studies used long, face-to-face interviews and were not anonymous (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008; Maruschak et al., 2010), which could be concerning for parents fearing negative consequences based on honest answers to survey questions (i.e., child protection involvement). It is important to note that our study highlighted that the vast majority of people in Minnesota prison were parents and interested in parenting classes.

The results were presented to the Commissioner of Corrections and his leadership team. We were thoughtful about how we presented these findings. We wanted our presentation to be brief, with plenty of time to hear from the team about the potential implications of the study for correctional practice (e.g., parenting classes) and policy. We also wanted to leave them with something that quickly and easily summarized our findings, so we developed a two-page infographic (see Learn More box) that could be easily shared (Shlafer, 2015).

The Impact of the Findings

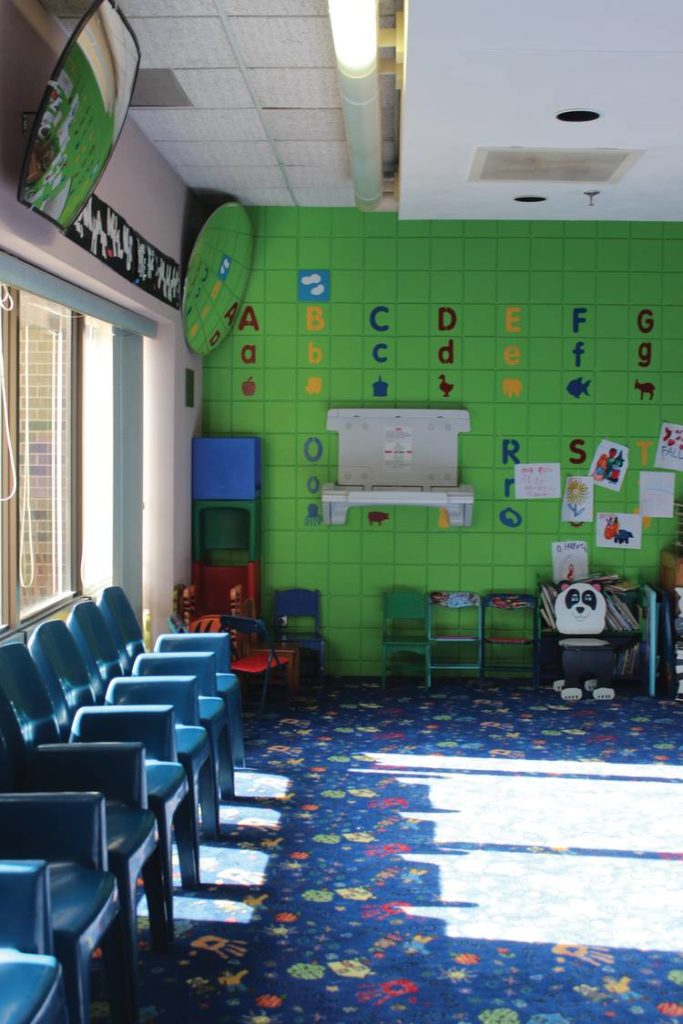

Results from this study directly informed conversations with corrections administrators about changes in policies and practices that affect incarcerated parents and their children. For example, the data prompted a conversation about how to improve the visiting environment at one of the prisons. Ultimately, changes were made at Minnesota’s only women’s prison to enhance the visiting space, including providing more developmentally appropriate books, toys, and artwork; adding bright, child-friendly carpet; painting the wall; and adding a changing table.

Years later, results from this study are still shared and commonly cited when developing practice and policy. During the 2019 Minnesota legislative session, data from this study were used to provide support to two legislative proposals. One legislative proposal focused on family impact statements, or documentation about defendants’ parental status and families to inform sentencing and supervision (2019 Minnesota House File 591), and another on programming to support visits between children and their parents in Minnesota prisons.

Parents in Minnesota Jails

It did not take long for the results from our study of parents in Minnesota prisons to attract interest from the local jail administrators. After presenting results from our prison study at a local conference, one jail administrator expressed concern to the first author [RS] that the prison results were interesting, but did not capture the thousands of parents held in county jails.

Conducting a similar study in jails posed different challenges. There are 87 counties in Minnesota, and nearly every county has its own jail. The state does not have a system that determines the number of people in jail on a given day. These two factors made it difficult to determine how many people in jails were parents.

In order to conduct this study, we knew that convincing jail administrators to participate would take encouragement from their corrections colleagues. We partnered with the Association for Minnesota Counties and the Minnesota Sheriff’s Association to think through the study design, logistics, and site recruitment. We were fortunate to have support from a former director of a local detention center who had a long history in corrections and many contacts with sheriffs, jail administrators, and jail programmers across the state who offered to make personal phone calls to jail programmers in each county to explain the study and invite each jail to participate. This approach paid off; 81% of all facilities in the state administered the survey and returned responses.

We also knew that we were going to have to work with the realities of collecting data in more than 80 different jails. Unlike prisons, jails have rapid turnover, with thousands of people cycling in and out of jails each day (Zeng, 2019). This turnover meant that we could not use the same methods that we used in the prison study, because we could easily and unknowingly double-count someone who was in and out of jail, and back in again. To address this issue, we needed to survey everyone on a single day. We again turned to our corrections colleagues to help us determine how we could do this with minimal disruption to jail operations.

Ultimately, we developed a brief, anonymous, paper-and-pencil survey to assess the parenting status of adult men and women held in jails across the state. With lessons learned from the survey of parents in Minnesota prisons, we made some key changes, including: (1) translating the survey into Spanish and providing a study information sheet in Spanish; (2) adding questions to capture the respondent’s race and ethnicity, as well as their employment and residence status pre-arrest; (3) revising a question to ask both male and female participants about whether they or their partner was pregnant, as well as adding a response option to this question of “I don’t know.”

Nearly 6% of mothers reported that they were currently pregnant, and an additional 5% were unsure if they were pregnant.

Survey Results

Within days of fielding the survey, we started receiving unsolicited letters from fathers in jails across the state. One father wrote, “I took your survey. Thank you for doing this. No one has ever asked me if I’m a dad.” Clearly, for some, simply asking if they were parents on our brief survey was validating and prompted many to think more deeply about how incarceration has impacted their children and families. Another father wrote, “Incarceration has no doubt hampered my abilities as a parent, as a provider, as a role model and most definitely has placed a toll on me mentally and most definitely emotionally.”

The results of this brief survey provided a snapshot of the characteristics of parents in jail and information about their minor children. About 2,680 men and women in county correctional facilities in Minnesota completed the survey. Respondents ranged in age from 18 to 86 years old and were mostly men (82%). We found that most respondents (79%) identified as a parent, and 69% were a parent of one or more child(ren) less than 18 years old.

We were primarily interested in the experience of parents with minor children, and our analysis of the survey data focused on this group. The average age of parents with minor children was about 33 years old. Native American people are disproportionately represented in the Minnesota criminal justice system, and our survey results also reflected this overrepresentation (Prison Policy Initiative, 2004). Most parents with minor children identified as White (53%); about 21% as Black/African American; about 14% as American Indian/Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic; about 9% as multiracial; 3% as Asian; and slightly less than 1% (0.9%) as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander. Sixteen percent of parents with minor children also identified as Hispanic or Latino.

Parents with minor children reported having between 1 and 14 children, and an average of between 2 and 3 children under 18 years old. Most of the children were in middle childhood or younger, as presented in Table 1.

We also wanted to understand the potential impact that incarceration of a parent may have on a child’s household income. About 56% of parents with minor children reported being employed in the month before their arrest. More fathers with minor children (61%) were employed in the month before their arrest compared to mothers with minor children (32%).

Incarceration of a parent, even for a short time, is potentially disruptive to a child’s housing (Casey, Shlafer, & Masten, 2015). Of fathers with minor children, 65% were living with one or more of their children in the month before their arrest. Similar to the proportion of fathers with minor children, about 64% of mothers of minors were living with their children in the month before their arrest.

We also hoped to understand how incarceration may impact families during especially vulnerable periods, such as during pregnancy. Nearly 9% of fathers with minor children reported that their partner was pregnant, and an additional 6% were unsure whether their partner was pregnant. Nearly 6% of mothers reported that they were currently pregnant, and an additional 5% were unsure if they were pregnant.

We also asked respondents about their interest in participating in a parenting class if one was available during incarceration. About 78% of fathers and about 85% of mothers expressed interest in such a class. Although many correctional facilities offer parenting classes, few programs have been designed specifically for this population, and most have not been rigorously evaluated (Dallaire & Shlafer, 2018; Loper, Clarke, & Dallaire, 2019). In their review of parenting programs for incarcerated mothers and fathers, Loper and colleagues (2019) identified 38 studies that evaluated programs for incarcerated parents, more than half (57%) of which focused on mothers. They found that such programs generally have positive impacts on parents’ knowledge and attitudes, well-being, and stress (Loper et al., 2019).

We also looked specifically at parents with young children, given the potential opportunities for early intervention with these families. About 58% of parents of minor children had at least one child 5 years old or younger. Men were slightly more likely than women to report having a young child. In general, most of the results of this subgroup of parents with young children were similar to the results for all parents with minor children. Compared to all parents of minor children, however, a slightly higher percentage of parents with young children, 70%, lived with their children in the month before their arrest. Similar to all parents of minor children, more than half (about 56%) of parents of young children reported being employed in the month before their arrest. About 82% of parents of young children indicated an interest in a parenting classes if available.

Finally, we wanted to use these data to estimate the impact of incarceration in county jails on the state’s population. In 2014, the average daily jail population in the state of Minnesota was approximately 5,960 inmates (Vera Institute of Justice, 2015). Our survey results indicated that 69% of men and women held in county correctional facilities were parents with minor children, and that parents with minor children had, on average, 2.4 children. Thus, we estimated that on any given day, about 9,898 children under 18 years old in Minnesota have a parent currently incarcerated in a county jail.

The data prompted a conversation about how to improve the visiting environment at one of the prisons, and changes were made at Minnesota’s only women’s prison to enhance the visiting space. Photo courtesy of Minnesota Correctional Facility of Shakopee.

The Impact of the Findings

From the beginning we knew that it would be important to share the data with each county in a way that could be useful. We created another infographic summarizing the key findings and prepared a county-by-county report (Shlafer & Saunders, 2017). We presented at the Minnesota Sheriff’s Association annual jail administrator’s conference and, after the presentation, we provided copies of the full report, infographic, and county data tables prepared for each jail administrator.

What has transpired since has been exciting. Over time, this study has informed many facets of policy and program decisions and has been used to improve services for both parents who are incarcerated and the children who are impacted by parental incarceration. Several counties reached out to us to follow up on their data and stressed the importance of having information about parental status, which filled a gap in existing knowledge. In addition to preparing a technical summary, we also created an easily digestible infographic which was a key resource to county and facility administrators.

Several counties described their plans to use the data to inform practices, policies, and procedures. A data analyst in Crow Wing County planned to distribute our report to colleagues, as they were exploring interventions that focused on promoting family well-being among individuals in their jails. These data sparked collaboration between the early childhood coordinator and the county jail administrator in Douglas County to increase support for incarcerated parents and their children, including “decorating” the jail visiting room with furniture and supplies that would be more welcoming to children, exploring partnerships with family home visiting services for parents after release, and searching for a parenting curriculum to develop a parenting and self-improvement class in the jail.

Carlton County also reported several ways that these data about incarcerated parents and their children informed their work. They described the importance of having a better understanding about the scope of this issue, the proportion of adults in jail who are parents, and the proportion of the local school population that is experiencing the incarceration of a parent. Armed with data on this issue, the jail developed the Family Friendly Jail Initiative—in collaboration with the sheriff, the county’s school district, and others—which has worked to improve the visiting spaces in their jails to create a more positive experience for children, and to develop a parenting class for the men and women in jail. Participants have expressed appreciation for the parenting class as they work to address how their incarceration has impacted their children (Lund, 2019).

An administrator in Washington County summarized the value of these data for policy making:

Data help us to make knowledgeable decisions concerning changes to current practices, policies and procedures, new programming and equipment that we purchase. Every dollar we spend must be counted for and must meet our agency mission. These data help us to train and educate our staff on best family strengthening practices and the impact, such as [adverse childhood experiences], has on children of incarcerated parents. The data help us develop appropriate responses to relevant issues and create evidence-based programming. The data also help us get out of our silos and develop a community-based approach to tackle these problems.

Despite these successes, we know there are important limitations to our findings. First, our results provide only a snapshot of parents in Minnesota prisons and jails. We do not have a system to identify parents or—more important—provide them with tailored services to meet their needs. Urban Institute published a report outlining model policies and practices for strengthening families affected by incarceration, including recommendations for intake and assessment (Peterson et al., 2019). Developing a system to regularly assess the parenting status of adults in Minnesota’s prisons and jails will be an important next step for the state. A second limitation of these studies is that the data only give an initial sense of the scope of the problem in the state, but they do little in terms of helping to identify solutions. Continued collaboration with key decision makers and families directly affected is critical to identifying and implementing new policies and programs to support families.

When a parent goes to jail, children may experience challenges at home, in school, and in their communities.

These studies offered key information about parents in prisons and jails in Minnesota and further facilitated conversation among key stakeholders to strengthen families in the context of incarceration. Our study about the parental status of men and women in jail had snowballed from our initial project to understand this issue among men and women in prison. After hearing the interest of county administrators in the prison study and realizing there were no data about men and women in jails, we capitalized on this opportunity to conduct research that would have a concrete impact on policies and programs. These concrete examples of changes implemented by county administrators further drives our collaborations and partnerships with communities and corrections. Through this research and collaboration with stakeholders across the state, we have come to some key conclusions and recommendations for other researchers dedicated to this work. We recommend fostering collaborations that aim to strengthen families affected by incarceration, including systematic data collection to identify incarcerated parents and their children who may benefit from support; increasing opportunities for meaningful parent–child contact; enhancing visiting spaces to make them more developmentally appropriate and child friendly; implementing evidence-based programs for incarcerated parents; and offering supports for caregivers in the community (Peterson et al., 2019)

When a parent goes to jail, children may experience challenges at home, in school, and in their communities, including financial and material hardship, unpredictability in family relationships, housing and school mobility, difficulty with school relationships and performance, poor physical health, struggles with mental health, and social and institutional stigma (Eddy & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2019). Given the impact of parental incarceration on children and families, along with the high proportion of individuals in prisons and jails that are parents with young children, we recommend collaborations between families directly affected, corrections administrators, local agencies, nonprofit organizations, and universities to create or strengthen practices and policies for incarcerated parents and their children.

Learn More

Parents in Minnesota Prisons and their Children Infographic

Authors

Rebecca Shlafer, PhD, MPH, is a developmental child psychologist in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota’s Medical School. She has led numerous projects examining the impact of incarceration on children and families. She provides training and technical assistance to early childhood educators, social workers, jail administrators, and lawyers and about parental incarceration and child development.

Lauren A. Hindt, MA, is a doctoral candidate in the clinical psychology program at Loyola University Chicago. Her program of research aligns with her clinical commitment to strengthen families and support children from underserved populations, with an overarching goal of improving health equity and reducing disparities. Her current research examines factors that promote well-being among families in the contexts of parental incarceration, foster care, and chronic illness.

Jennifer B. Saunders, MSW, is a doctoral candidate in health services research, policy and administration at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health. Her research interest is health policy that impacts reproductive-age women and their families.

References

Casey, E. C., Shlafer, R. J., & Masten, A. S. (2015). Parental Incarceration as a risk factor for children in homeless families. Family Relations, 64(4), 490–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12155

Dallaire, D. H., & Shlafer, R. J. (2018). Programs for currently and formerly incarcerated mothers. In C. Wildeman, A. R. Haskins, & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds.), When parents are incarcerated: Interdisciplinary research and interventions to support children (pp. 83–107). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from source link

Eddy, J. M., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (Eds.). (2019). Handbook on children with incarcerated parents. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16707-3

Edwards, F. (2016). Saving children, controlling families: Punishment, redistribution, and child protection. American Sociological Review, 81(3), 575–595.

Gelb, A., & Denney, J. (2018). National prison rate continues to decline amid sentencing, re-entry reforms: More than two-thirds of states cut crime and imprisonment from 2008-16. Retrieved from source link

Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Parents in prison and their minor children. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from source link

Lamb, K., & Dorsey, R. (2014). Survey of incarcerated parents in Ohio prisons. Retrieved from source link

Loper, A. B., Clarke, C. N., & Dallaire, D. H. (2019). Parenting programs for incarcerated fathers and mothers: Current research and new directions. In J. M. Eddy & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds). Handbook on children with incarcerated parents: Research, policy, and practice (pp. 183–203). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Lund, J. (2019, October 24). Carlton County Jail offers inmate parenting classes. Pine Journal. Retrieved from source link

Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Medical problems of prisoners. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from source link

Maruschak, L., Glaze, L., & Mumola, C. (2010). Incarcerated parents and their children: Findings from the Bureau of Justice Statistics. In J. Eddy & J. Poehlmann (Eds.), Children of incarcerated parents: A handbook for researchers and practitioners (pp. 33–51). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Minnesota Department of Corrections. (2015). Minnesota Department of Corrections adult inmate profile. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Department of Corrections.

Murphey, D., & Cooper, P. (2015). Parents behind bars: What happens to their children? Retrieved from source link

New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. (2013). Children of incarcerated parents in New York state. Retrieved from source link

Peterson, B., Fontaine, J., Cramer, L., Reisman, A., Cuthrell, H., McCoy, E. F., Goff, M., & Reginal, T. (2019). Model practices for parents in prisons and jails: Reducing barriers to family connections. Retrieved from source link

Pew Center on the States. (2011). State of recidivism: The revolving door of America’s prisons. Retrieved from source link

Prison Policy Initiative. (2004). Native Americans are overrepresented in Minnesota’s prisons and jails. Retrieved from source link

Shlafer, R. (2015). Parents in Minnesota prisons and their children. Retrieved from www.rebeccashlafer.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ MNPrisonersMinorChildren.pdf

Shlafer, R., Duwe, G., & Hindt, L. (2019). Parents in prison and their minor children: Comparisons between state and national estimates. Prison Journal, 99(3), 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032885519836996

Shlafer, R., & Saunders, J. B. (2017). Parents in Minnesota jails and their minor children. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2016). Quick facts: Minnesota. Retrieved from source link

Vera Institute of Justice. (2015). Incarceration trends. Retrieved from source link

Walmsley, R. (2018). World prison population list. Retrieved from source link

Zeng, Z. (2019). Jail inmates in 2017. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved from source link