Jane Bernzweig, First 5 Alameda County, Alameda, California; Christina Branom, Applied Survey Research, San Jose, California; and Jane Wellenkamp, First 5 Alameda County, Alameda, California

Abstract

Consistently, kindergarten readiness assessments in Alameda County, California, have shown fewer than half of students are fully ready for kindergarten and for some subgroups the percentage is even lower. Overall, our research shows that the strongest predictors of kindergarten readiness are child health and well-being and the child’s attendance in early care and education, both of which are correlated with race, ethnicity, and family income. We offer recommendations on the types of investments in families, communities, and schools that funders can make using an equity-informed lens with input from parents and local residents. Drawing attention to socioeconomic disparities within communities and schools, we show how local investment in the safety net, housing, neighborhoods, and workforce serves a parent-informed policy advocacy agenda to enable all children to be ready for kindergarten.

Since 2008, First 5 Alameda County has partnered with Applied Survey Research to conduct regular assessments of kindergarten readiness in Alameda County, California. The studies have helped to gauge the effectiveness of our community’s kindergarten readiness efforts and to inform recommendations for policies, practices, and programs with the potential to improve kindergarten readiness in the county.

Consistently, we have found that fewer than half of students in our community are fully ready for kindergarten, and that among some subgroups and neighborhoods, the percentage is much lower. The most recent study, conducted in fall 2019 with a countywide representative sample of 1,560 kindergarteners, found that 44% of children overall were fully ready, while 30% of low-income children (i.e., from families earning less than $35,000/year), 32% of African-American children, and 28% of Latinx children reached this benchmark (Applied Survey Research, 2019). In our 2018 longitudinal study (Applied Survey Research, 2018), we found that skill gaps observed between different subgroups at kindergarten entry generally persisted into third grade and even widened for some children.

To better understand and address these consistent findings, we have evolved our approach to the study of kindergarten readiness. In 2019, we devoted additional resources to examine and document results by subgroups, including by socioeconomics, race/ethnicity, gender, language, and neighborhood. We also expanded our look at the role of communities and schools in determining kindergarten readiness, components of readiness that are as important to measure as child and family readiness, but often overlooked (ECDataWorks, 2018; National Education Goals Panel, 1995; Pianta & Kraft-Sayre, 2003). We particularly focused on the impact of factors that can be responsive to intervention; our revised, equity-based framework has the potential to open up new opportunities for local action.

Overall, our research shows that the strongest predictors of kindergarten readiness are child health and well-being and the child’s attendance in early childhood education (ECE) in the year prior to kindergarten, both of which we have found to be correlated with race, ethnicity, and family income. Readiness disparities have roots in social, racial, and economic inequity, but our findings also suggest that targeted investments and family-friendly policies may help reduce these disparities. In this article, we offer recommendations on the types of investments in families, communities, and schools that funders can make using an equity-informed lens and with input from parents and local residents. (See Box 1.)

Box 1. First 5 Alameda County’s Investments

Investments by First 5 Alameda County include:

Economic supports for families, including families without permanent shelter, and for center-based and family child care providers

Workforce development, quality improvement coaching, and training for early childhood education programs and family, friend, and neighborhood providers, and parent–child playgroups

Early identification of developmental concerns, referrals, and navigation for families

Expansion of father-friendly and father-specific services

Expansion and coordination of services in under-resourced neighborhoods and opportunities for parent leadership

Convening of city leaders to increase their focus on early childhood

Investment in kindergarten transition activities in school districts

Policy advocacy that addresses the socioeconomic needs of families and caregivers, including expanded earned income tax credit, increases in CalWORKs grants, improved housing and transportation supports, and subsidized quality child care

Environments and Systems Affect Children’s Readiness

To measure kindergarten readiness, we used a teacher-completed tool developed by Applied Survey Research, the Kindergarten Observation Form, to assess children’s motor, social–emotional, and cognitive readiness skills in the first month of school entry. We also surveyed families about a variety of child and family experiences and living conditions and looked for relationships between these and children’s readiness scores.

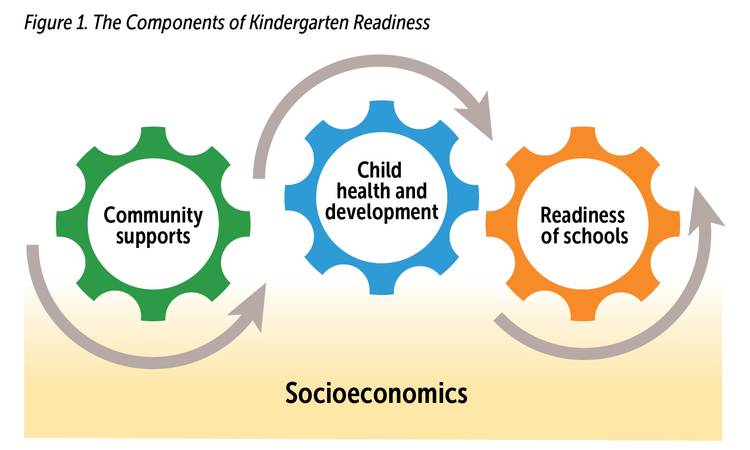

However, a narrow focus on child and family contributions to readiness fails to recognize the powerful interplay of contextual and societal factors on children’s development and transition to kindergarten (Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2000). Children grow up embedded within interactive systems of family, community, and school (see Figure 1). There is growing recognition that better preparing children for kindergarten calls for addressing structural inequities, supporting the “readiness” of each system, and fostering close and collaborative relationships among them. “Ready” communities are rich with supports to help all families meet their basic needs and promote children’s development, while “ready” schools smooth the transition between home and school, are committed to the success of each child, and are responsive to the strengths and needs of entering children and their families.

A broader look at each of these systems helps to reveal the socioeconomic inequities that result in unequal access to resources that support kindergarten readiness and later achievement. For example, in our longitudinal study, schools with a higher percentage of children who entered kindergarten “less ready” but then made gains in academic achievement by third grade were socioeconomically advantaged schools (Applied Survey Research, 2018). Supporting readiness requires investing differently, and advocating for policy change in larger systems and structures (e.g., living wages, affordable child care, paid family leave, affordable housing, transportation) to promote families’ ability to access income and build wealth, and create more equitable resource distribution across neighborhoods and schools.

Recognizing the interplay between family well-being and community and school supports, we engaged parents to inform our policy-related recommendations and funding decisions to address some of the structural issues acting as impediments to student success. Interpretations of data and decisions about funding and services are too often made in the absence of family and community input and participation. We shared preliminary results of the 2019 assessment with families via two focus groups conducted in partnership with a school-based family resource center that served a predominantly low-income Latinx, Asian, and African-American population. One of the focus groups was comprised of members of a Parent Action Research Team that was exploring community residents’ views about kindergarten readiness. Their comments and feedback were incorporated into our study to highlight parent voices, support local parent leadership and advocacy, and guide next steps to strengthen readiness in the community.

All of these efforts helped us to clarify and highlight the policy and practice implications of our findings, to help us move from study results to action. These, in turn, are helping to identify new ways to invest in our community.

Child and Family Readiness

Across the years of our study and in our longitudinal research, we have found that the greatest moveable or malleable child or family factor affecting kindergarten readiness is child health and well-being, which, in our recent study, we found was tied to socioeconomics, housing stability, and parental stress.

Children who came to school with well-being concerns, particularly those displaying signs of tiredness or hunger, had lower readiness levels than their peers. Just over 1 in 5 children appeared tired, sick, or hungry on at least some days, according to their teachers. These children with well-being concerns were more likely to live in families with lower incomes; higher levels of stress concerning issues like work, money, and paying the bills; and housing instability, including changes in residence and periods of homelessness.

“Homelessness, lack of food, kids going to bed hungry. If you don’t have proper housing, shelter, it’s hard. [It] makes things unstable for the kids.” –Parent focus group participant

Prior attendance in ECE is another key factor consistently associated with kindergarten readiness. Children who had attended ECE programs, especially African-American and Latinx children and children in low-income families, had higher readiness than children without these enriching experiences. However, children from lower income families, English-language learners, and Latinx and African-American children were also less likely to have access to formal ECE than their peers, in part because, according to the families in our study, quality ECE is often unaffordable.

“Preschool is a community support where children learn to express themselves–they use their voice, learn conflict resolution and problem solving.” –Parent focus group participant

Other malleable child and family factors that contributed to readiness, according to our study, included less exposure to screen time, children’s resilience (e.g., the ability to adjust well to changes in routine and calm themselves), families reading together, and fathers’ use of community resources. All of these factors are related to socioeconomics, likely because families with more resources, time, and less stressful living conditions, have more opportunity to engage in and support these activities and abilities.

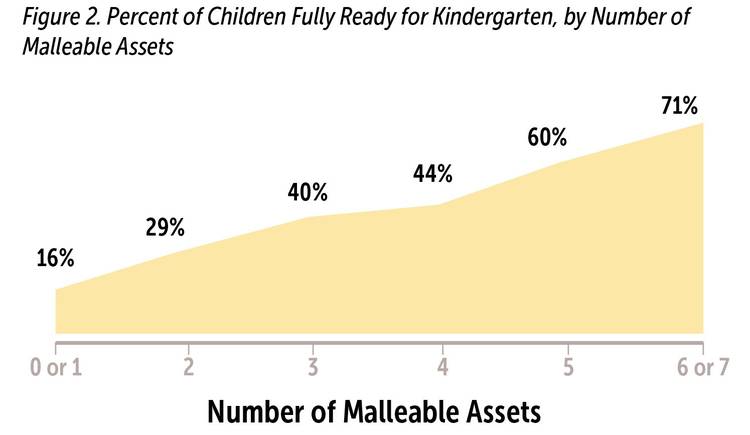

Importantly, we found that the positive effects of these malleable assets were cumulative. In combination, these factors were associated with substantially increased readiness among children in our sample. Only 16% of children who had no more than one of seven assets were fully ready compared to 71% of children who had at least six assets (see Figure 2).

When we shared our results with parents in the focus groups, the findings resonated with their experiences. Their suggestions for next steps are reflected in our policy recommendations and funding priorities (see Table 1).

Table 1. Child and Family Policy Recommendations and Key Investments

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: ECE = early childhood education; TANF = Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

Ready Communities

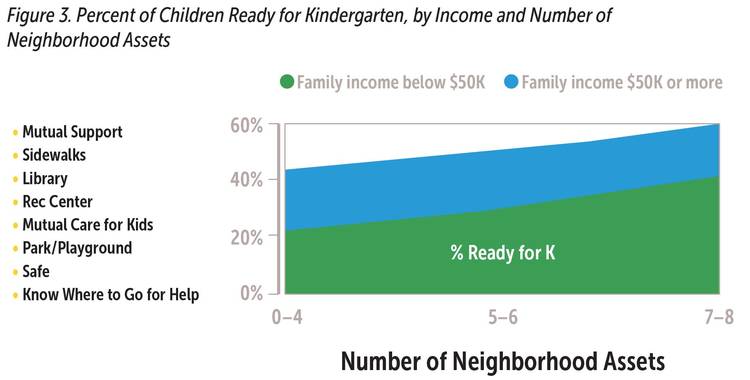

This year, we expanded our study to explore the readiness of communities to support families and promote optimal child development. We found that children’s readiness is significantly related to the presence of neighborhood assets, even after accounting for family income. That is, as the number of neighborhood assets in a community increased, so did readiness for children in both lower income and higher income families (see Figure 3). Assets that had the strongest relationship with readiness included the presence of mutual support among community members, sidewalks and walking paths, and libraries and bookmobiles. But it is important to note that lower income families, Latinx and African-American families, and English-language learners, most of whom were Latinx, tended to live in neighborhoods with fewer assets.

“If the parks were safe and inviting, I wonder if kids would have less screen time and be outside more.” –Parent focus group participant

“[We need] more funding for resource programs that are trying to help their communities. Every year it seems like they’re taking away more funding.” –Parent focus group participant

Our findings suggest policies that strengthen neighborhood resources can help close the gap in children’s readiness. Parents told us they would like more investment in their local communities, including safe outdoor play spaces, libraries and bookmobiles with bilingual and multicultural books, playgroups, and parent groups (see Table 2).

Box 2. Bilingualism

Bilingualism has been associated with improved academic performance and social outcomes, and also benefits the communities in which students eventually live and work (Castro et al., 2011). Yet in this study, only 45% of English-language learner students were taught by a bilingual teacher and even fewer were in bilingual education programs. At one of our schools with a bilingual English–Spanish immersion program, we saw relatively high levels of readiness among Latinx children. Such programs may help Spanish-speaking Latinx children and their families’ better transition to kindergarten. Similarly, some research points to the benefits for children’s academic performance when they are taught by a teacher of the same race/ethnicity (Boudreau, 2020; Dee, 2005). Only a third of the children in our sample were taught by a teacher of the same race/ethnicity, further underscoring the importance of increasing the diversity of the teacher workforce.

Table 2. Community-Related Policy Recommendations and Key Investments

|

|

|

|

Ready Schools

To explore the third component of readiness–the readiness of schools to support entering kindergarteners and their families–we asked about teachers’ background, training, and experience, and the presence of kindergarten transition supports such as orientations, open houses, family social events, communication between pre-K and kindergarten teachers about students and curricula, parent–teacher meetings, and home visits. We found that classrooms with a high proportion of fully ready children were more likely to be in schools that offered multiple kindergarten transition support activities. The most common kindergarten transition support offered by schools was an orientation session, reported by 69% of teachers. Fewer than half of teachers indicated that their school provided other types of transition supports, and 15% of teachers said their school did not have any formal transition supports.

“[It is] good [for schools] to meet children where they are. Some kids never even go to preschool.” —Parent focus group participant

Parents in our focus group said that offering more kindergarten transition activities, especially for children who did not have prior preschool experience or experienced adversity in their early years, was an important way for schools to better support children’s readiness. In addition, parents expressed a desire for a more diverse teacher workforce (see Box 2), more teacher training on promoting child resilience, and more health and family support services at schools like food pantries and health and dental clinics (see Table 3).

Table 3. School-Related Policy Recommendations and Key Investments

|

|

|

|

Conclusion

In this time of expanding health and economic disparities and a social reckoning around race and class, the early childhood community has a major role to play in highlighting the importance of investing early in children’s lives and attending to broader social forces and contexts that shape and support children’s development. This role includes drawing greater attention to the socioeconomic disparities within the communities and schools where families with young children live and learn. Our work indicates the importance of local system change in support of families’ lives, including investments in a secure safety net, stable housing, neighborhood assets, and workforce development. These efforts in turn can inform state and federal policy. It is our intention to include parent and community voices earlier and deeper in our future studies. We believe it is imperative to involve residents and parents who are contending with the inequities we are documenting and studying and that exist as a result of ineffective public policies. Doing so will allow us to pursue a parent-informed public advocacy agenda and to provide programs and investments that can better address the needs of families and communities. Furthermore, data is a resource for parent- and community-led efforts in a commitment to action.

We hope our data and recommendations will resonate with others in the field and lead to changes in kindergarten assessments, policies, and programs that will enable all children, communities, and schools to be fully “ready” for kindergarten.

Acknowledgments

The studies on which this article is based were conceptualized and directed by Kristin Spanos, CEO, First 5 Alameda County; Lisa Forti, director of planning, policy, and evaluation; and Carla Keener, director of programs. The First 5 Alameda County Kindergarten Readiness Team also includes Erika Kuempel, communications specialist, and Vincent Cheng, senior Help Me Grow community liaison, who have been integrally involved with our kindergarten readiness work. We are grateful to all of the above for their guidance and important contributions. We also thank the teachers and families who have partnered with us on our kindergarten readiness studies.

Suggested Citation

Bernzweig, J., Branom, C., & Wellenkamp, J. (2021). New directions in kindergarten readiness. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(Supp.).

Authors

Jane Bernzweig, PhD, is an evaluation specialist at First 5 Alameda County in California. She served as project manager for the 2019 Alameda County Kindergarten Readiness Assessment and specializes in program evaluation in early childhood education settings. She has conducted evaluations of mental health consultation programs, family child care, and the integration of family partners into Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment benefit-funded programs. Prior to coming to First 5 she was a research psychologist in the Division of General Pediatrics and the Department of Family Health Care Nursing at University of California, San Francisco, where she co-authored publications on doctor–patient communication, pediatric decision-making, and child care health and safety. Her doctoral training was in social and developmental psychology. She completed a National Institute of Mental Health post-doctoral fellowship in children’s prevention research and holds infant and early childhood mental health certification.

Christina Branom, PhD, is director of research and school readiness specialist at Applied Survey Research, where she has been coordinating and leading kindergarten readiness assessments since 2013. In addition to her expertise in school readiness, she has led research and evaluation projects in the areas of language development, achievement motivation, and child maltreatment. Her work has been presented at national conferences, including the American Educational Research Association annual meeting, and published in peer-reviewed journals, including Child Psychiatry and Human Development. Dr. Branom earned her master’s degree in psychology from Stanford University and a master of social welfare and doctorate in social welfare from University of California, Berkeley.

Jane Wellenkamp, PhD, is an evaluation specialist at First 5 Alameda County in California. With a background in psychocultural anthropology, she has conducted ethnographic research and program evaluation for national and state demonstration programs including the Comprehensive Child Development Program, Early Head Start, Center for Substance Abuse Prevention High-Risk Youth Program, and the Non-Custodial Parent Employment and Training Project. Her kindergarten transition work includes research in Venice, CA, for the Harvard Family Research Project’s School Transition Study, and an evaluation of First 5-funded summer pre-kindergarten programs. Her publications include The Thread of Life and Contentment and Suffering: Culture and Experience in Toraja, both co-authored with Dr. Douglas Hollan.

References

Applied Survey Research. (2018). Kindergarten readiness and later achievement: A longitudinal study in Alameda County. link

Applied Survey Research. (2019). Kindergarten readiness 2019: Alameda County comprehensive report. link

Boudreau, E. (2020). Measuring implicit bias in schools: A new study finds evidence that teachers’ implicit bias may lead to unequal student outcomes. Harvard Graduate School of Education. link

Castro, D. C., Páez, M. M., Dickinson, D. K., & Frede, E. (2011). Promoting language and literacy in young dual language learners: Research, practice, and policy. Child Development Perspectives, 5(1), 15–21.

Dee, T. S. (2005). A teacher like me: Does race, ethnicity, or gender matter? American Economic Review, 95(2), 158–165.

ECDataWorks. (2018). School readiness reporting guide: Guidelines and tools for creating and using school readiness reports. link

National Education Goals Panel. (1995). Reconsidering children’s early development and learning: Toward common views and vocabulary. Washington, DC: National Education Goals Panel. https://govinfo.library.unt.edu/negp/reports/child-ea.htm

Pianta R. C., & Kraft-Sayre M. (2003). Successful kindergarten transition: Your guide to connecting children, families, & schools. Brookes.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(5), 491–511.