Lauren Perez, Esther Wong, and Maria Seymour St. John, Infant-Parent Program, University of California, San Francisco

Abstract

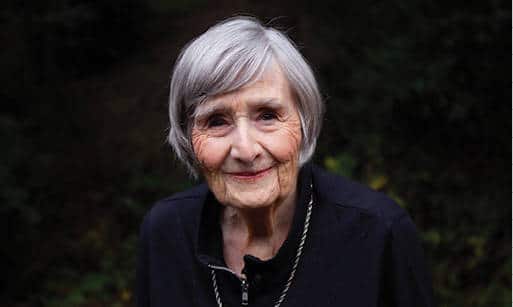

Jeree H. Pawl, a luminary in the field of infant mental health and a founding member and past president of the board of directors of ZERO TO THREE, died November 19, 2021, at the age of 91. Her contributions to the field were immeasurable. Through clinical innovation, administrative leadership, writing, public speaking, teaching, training, and pioneering the practice of reflective supervision, Dr. Pawl helped to shape the ways we all understand our charge in this work. She advocated for inclusive, interdisciplinary collaboration on behalf of infants and young children and their parents and caregivers. She knew that babies and their parents need a workforce that is well trained, well respected, and well supported, and she worked tirelessly to bring this into being. Dr. Pawl is perhaps most well known for her adage that “How you are is as important as what you do.” In this article we reflect on some of the ways in which we feel her influence in what we do—and how we are.

Jeree H. Pawl’s career as a psychologist was summarized in a life tribute published in the San Francisco Chronicle on December 18, 2021 (Celebrating the Life of Jeree H. Pawl, 2021). Soon after earning her doctorate, Jeree joined world-renowned social worker and psychoanalyst Selma Fraiberg in the Child Development Project at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, where the team collaboratively innovated infant– parent psychotherapy, a ground-breaking approach to addressing difficulties in the relationships between infants and their parents. In 1979, Fraiberg and her clinical team were invited to join the Department of Psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. They started the Infant-Parent Program at San Francisco General Hospital to address the needs of very young children and their families, as well as the community professionals who served them. In 1981, Jeree assumed the directorship of the program, which she stewarded expertly for nearly two decades. While tending to the daily functioning of this community-based program in the heart of San Francisco’s Mission district, Jeree was also instrumental in the development of ZERO TO THREE and was elected president of the board of directors in 1994. Her professional writing and speaking helped the world to see and feel the vital importance of the field as it was being born.

Jeree possessed an almost uncanny ability to “feel her way” into the experience of others. She helped adults to understand the meanings expressed in the behavior of infants and toddlers. Parents too felt understood, even in their most bitter conflicts, and were able to embody more fully the parent they wished to be, thanks to her unflinching attention to their experience. Practitioners across disciplines felt heard and valued by her, and their commitment to working on behalf of infants, toddlers, families, and caregivers was galvanized by her guidance and vision. A key element of that vision was captured in her famous adage, “How you are is as important as what you do.” Through her writing and presenting, teaching and training, consultation and supervision, Jeree mentored and inspired thousands of professionals, seeding the field and inspiring programs and policies regionally, nationally, and worldwide.

We are three infant and early childhood mental health workers who are part of the present-day clinical team at the University of California, San Francisco Infant-Parent Program. In the following sections, we each offer reflections on ways that we feel and recognize Jeree’s influence. We draw on and respond to excerpts from Jeree’s writings on a range of topics, appreciating how the work that we love, while responsive to pressing present-moment concerns, is sustained by intergenerational transmissions.

Hearing Jeree’s Voice: Maria’s Reflections

Jeree’s voice drew me into the field. In the context of a clinical psychology master’s degree program, I attended a course on child development in which the instructor showed video footage of infant–parent psychotherapy in action. Two parents interacted with their 4-week-old baby in ways that were—even to our untrained eyes—deeply disturbing. They moved the tiny, flailing body in space without supporting the head. They claimed that the baby bore malice toward them. They mocked him. They threatened him, ostensibly in jest. Throughout the entire interlude, which was hard to endure, a voice off-screen spoke to the parents. The voice was calm, deep, and modulated. Impossibly, it was simultaneously insistent and grave, and yet somehow light and open. Observations and questions were offered that clearly kept the highly guarded parents at their ease, while at the same time steadily driving toward awareness of the infant’s potential experience. This voice made it possible for us (the students) to attend to what was happening rather than recoil. It calmed our horror, commanded our attention, and kindled our curiosity. The voice was Jeree Pawl’s, and I followed it to the Infant-Parent Program and into my life’s work.

Even in printed form, Jeree’s is a speaking voice. Many of her writings were originally talks, and pieces that were written for publication are worthy of reading aloud. Her turns of phrase are unexpected, so to listen is to learn something: indeed, to experience something. Yet, she is not preaching, or even teaching. She meets the reader half way; it is almost a conversation. She speaks not just to one’s professionalized self, who is doing a job, but to the whole person who is living a life. Here, for example, is a quotation from her 1994–1995 article on supervision:

A family with a child with a difficulty that troubles you particularly and with whom you cannot seem to find your balance—that belongs in supervision. Something about Arthur’s mother that rubs you entirely the wrong way and you realize you really snapped at her very unpleasantly today—that belongs in supervision. In effect, one is examining one’s practices and one’s responses to one’s work. One is also conceptualizing the underlying principles of that work from ever new perspectives and experiences over and over and over. (p. 24)

What Jeree describes here (the importance of considering countertransference phenomena in clinical supervision) and how she describes it (in colloquial terms, with a rhythmic cadence, and with humor) are equally important.

Jeree cultivated a professional culture where storytelling was recognized as a human need, a methodology for teaching and learning, and a healing activity. People who were supervised by Jeree recall roving conversations. Anything was fair game to discuss (likely a gift of the psychoanalytic roots of the Infant-Parent Program—deep confidence in the fruits of free association). It was not self-indulgent. Our own experiences—our idiosyncratic preoccupations, our wounds, our funny bones—were deemed to be important parts of how we inhabit our roles. The meandering was always in service of understanding more deeply the experiences of those in our care, furthering the pathways of connection and support. A range of structures may be appropriate to various service settings, Jeree suggests, but building in consistent supervisory relationships is critical because “I don’t think it is possible for any of us to do what we do without some good place to tell our tales” (1994–1995, p. 26).

Jeree and I worked together on the 1998 ZERO TO THREE publication How You Are Is as Important as What You Do in Making a Positive Difference for Infants, Toddlers and Their Families (though the adage was hers) that set forth some guiding principles in work with young children and families (see excerpt in Box 1).

These guiding principles continue to ground us in our daily work at the Infant-Parent Program. Twenty-one years later, Jeree and I collaborated on our last joint writing project—the afterword to my book on the Parent–Child Relationship Competencies (PCRCs; St. John, 2019). In many important ways the book, and indeed the entire PCRC framework, constitute an intergenerational transmission; they are grounded in Jeree’s ethics, wisdom, sensibility, and spirit. In our afterword we discuss learnings regarding the importance of grappling with power and privilege in reflective supervision, drawing on the work of leaders in this area (Hardy & Bobes, 2017; Hernández & McDowell, 2010; Noroña et al., 2012.) These authors critically examine the ways in which White dominant culture often suffuses clinical supervision, reproducing injurious patterns (Noroña et al., 2021). One avenue of inequity is reflected in the historic tendency for supervisors to remain cloaked in ostensibly professional anonymity rather than entering the supervisory relationship as embodied (raced, gendered, classed, and otherwise socially located) people. This pattern blocks collaborative reflection regarding axes of power and privilege within the supervisory relationship. We invoke the notion once again that “How you are is as important as what you do,” and go on to say, “We continue to believe this assertion to be true and easily lost sight of. In addition, we have come to understand that who you are is also of vital importance—that the [supervisee’s] and the supervisor’s embodied and socially located experiences must be recognized, reflected on, and factored in” (St. John, 2019, p. 280).

If you are reading these words, you are probably someone who works hard to make a positive difference in the lives of very young children. At ZERO TO THREE: National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families, we believe that this is the most important work in the world. The earliest years of life are the time of greatest human growth and development. They are also the time when caring adults have the greatest opportunity to shape a child’s future. How can we be sure that we are making the most of this opportunity?You have probably thought a great deal about this question yourself. As an experienced practitioner, program director, trainer, or consultant, you may be responsible for helping others—caregivers, family advocates, home visitors, parents, students, and volunteers—do their best to make a positive difference for each child and family with whom they work.

You may have discovered, as we have over the years, that human relationships are the foundations upon which children build their future. Babies’ and toddlers’ earliest relationships shape their expectations of other people, and of themselves. All of the relationships that touch very young children are important—the relationship between a baby or toddler and each member of his family, the relationships between a child and her caregivers, the relationships between a caregiver or home visitor and the child’s family, and relationships among adults in the child care or infant/family program setting.

For a baby or toddler, small positive changes in important, day-to-day relationships mean greater flexibility, a greater range of responsivity, and, perhaps, a greater sense of oneself as a worthwhile, competent, lovable person. For adults, respectful, reliable, and comfortable working relationships help us to achieve the shared goal of promoting young children’s healthy development. Positive changes in adults’ relationships allow growth—and sometimes healing—in adults and children alike.

Relationships are what they mean to the people in them. Meaning grows over time, built up by what each partner in the relationship does (and how the other partner experiences and understands what is done) and also by how each partner in the relationship is (and what the other partner learns from this). An adult feeds a baby—when the baby is hungry, or when it is convenient for the adult? in a lap that feels safe and familiar or with arms that communicate tension or disgust? A parent and a professional talk about a toddler—in a quiet, comfortable corner or on the run, when one or both are distracted or fatigued? with trust in each other or with suspicion or fear?

It makes a difference. How you are is as important as what you do.

If you believe that how you are is as important as what you do, you probably also know that this principle is not easy to put into practice. Ways of being depend on beliefs and attitudes, and these change slowly. Perhaps they have to be more “caught than taught.” And, in work with infants, toddlers, and families there is so much to do every hour, every day—how can staff, parents, administrators, or students find the time and energy to think about “how they are”?

Guiding Principles for “Being” and “Doing” With Infants, Toddlers, and Families

Our conviction that how you are is as important as what you do with very young children and their families has developed over several decades of working, studying, and teaching in the new field of infant/ family development. During this same period, we have discovered a handful of principles of interaction that have proven to be trustworthy guides in our efforts to be and do the best we can for babies, families, each other, and ourselves.

- Behavior is meaningful. The newborn’s gaze, the toddler’s “No!”, our avoidance of paperwork (or our need to complete it well before the deadline), the way a grandfather sings to a grandchild who speaks a different language from his own—all human behavior is full of meaning, and can be understood. Because behavior results from the interaction of many factors—including temperament, developmental stage, level of knowledge or skill, cultural background, and expectations of oneself and other people—the same behavior can have very different meanings. We cannot assume that our initial understanding of the meaning of another’s behavior is correct, or complete. We must also realize that our own behavior is likely to mean different things to different people.

- Everyone wants things to be better. Everyone knows what he or she wants, and some people think they know what other people should want. In fact, you can’t determine for other people what they should want. But you can try to understand how a child or adult’s specific wants (or desires or demands) stem from their basic human needs for safety, connection, meaning, and mastery. You can offer choices and explore possibilities.

- You are yourself and your role. A Spanish philosopher once observed, “I am myself and my circumstances.” How you are able to be and what you are able to do in your life depend on the strengths and limitations you were born with; the experiences you have had, and how you have understood those experiences; the resources available to you; and the culture, community, and times you live in. How you are and what you do in a specific role—as a provider of care for a group of very young children, as a partner to a particular parent in the care of a particular baby, as a supervisor, as the director of a program or agency, or as a teacher—depend on your knowledge, skills, attitudes, the human and material resources available to you, and expectations (yours and other people’s) of you in that role. When expectations differ, or conflict with what is possible, roles need to be clarified.

- Don’t just do something—stand there and pay attention. In work with infants, toddlers, and families, less is usually more. The impulse to protect, provide, or even to rescue is strong where babies or vulnerable adults are concerned. But we are more likely to make a positive difference in the development of young children and families if we refrain from “doing” and take time first to observe carefully, consider the many possible meanings of what we have seen and heard, seek more information, and ask questions that demonstrate our respect, interest, and capacity for empathy.

- Remember relationships! The key to quality in any service or program for very young children is the quality of relationships— relationships between the baby or toddler and his or her parents, between child and caregiver, between the child and other children, between professional and family, and among adults in the program. It is not an easy task to establish and sustain the deep, responsive, and respectful relationships among adults and children that are the hallmark of quality, but it is an essential one.

- Do unto others as you would have others do unto others. We call this the “platinum rule” of training, supervision, and mentorship. How you are and what you do with colleagues, supervisees, and students becomes a model for how professionals and parents relate to each other, and how adults relate to the infants and toddlers in their care.

Excerpted from Pawl & St. John, 1998

I am a White, cis-gendered, queer identified woman in my late 50s who has benefited from unearned privilege along axes of race, class, and nationality. Many of the intergenerational transmissions I received throughout my life have necessitated un-learning for me as I strive to interrupt patterns of injustice and align myself with racial and social justice. Such changes are not purely cognitive, nor even behavioral. They must be changes at the level of being. Intergenerational transmissions from Jeree, including most fundamentally the conviction that ways of being matter, forged for me the conceptual and experiential pathways to be different, and to cultivate and cherish opportunities to truly be with others across difference.

Jeree H. Pawl received the Lifetime Achievement Award from ZERO TO THREE in 2019. Photo: ZERO TO THREE

Receiving Transmissions During Pandemic Years: Esther’s Reflections

To be able to assess the effects of day care on a particular child…a parent must acknowledge—really know—that she or he is leaving the child with a particular person or set of people; the parent will have to notice what the child’s relationship with that caregiver is likely to be. (Pawl, 1990, p. 5)

If we can also find ways to help ensure mutually respectful, trusting, and ongoing relationships between parents and caregivers then we will have the best kind of shared care for the child. (Pawl, 1990, p. 6)

In my role as an early childhood mental health consultant at the Infant-Parent Program, I have been supported to carry forward Jeree’s insistence on the importance of focusing not solely on the behavior of children, but on the quality of the network of caregiving relationships. Ordinarily, the small but significant moments of connection between parents and caregivers during morning drop-off and afternoon pick-up form the foundations upon which an essential, trusting, rich partnership is built. Phone check-ins, in-person meetings, and parent–teacher conferences also add substance and robustness to this relationship. In addition, in this day and age, caregivers use text messages, emails, and various messaging and photo-sharing apps to help maintain an open line of communication with parents, often providing updates about children’s behaviors, developmentally remarkable moments, delightful social interactions, and new learnings throughout the day.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, when in many group care settings parents have been restricted from physically entering program facilities or have at a minimum needed to significantly limit their physical presence within them, child care and preschool providers and parents have exercised an extraordinary amount of creativity and adaptability. During this period, some providers decided to increase their use of any and every communication method that is not premised on in-person contact, in an effort to approximate for parents as best as possible the experience of entering into their child’s classroom and witnessing these important moments firsthand. Providers have also lined their entryways, designated “intake” areas, and outdoor-facing windows with photos, children’s artwork, and lovingly composed classroom newsletters. Phone calls and video conferences, which have at times been very difficult to schedule due to myriad and shifting pressures and limitations on both sides, have taken the place of spontaneous and organic chats at the classroom’s doorway or on the outdoor play yard at the beginning or end of the school day.

Of course, parents and providers have acutely felt the limitations and shortcomings inherent to these “next best thing” methods, adopted purely out of necessity. Parents have shown up during their designated drop-off and pick-up windows in spite of tight work schedules, transportation issues, and competing family demands. They have tried to keep their conversations with staff brief even when their curiosity, concern, and interest in their child urges them to ask more questions. And they have come up with plan Bs and plan Cs on the fly when classrooms and programs have needed to suddenly close due to COVID-19–related issues and concerns. Perhaps many parents have often felt like they’ve had no choice but to take a blind leap of faith that their child’s daytime caregivers are safe, trustworthy, and responsive to their child’s particular needs.

As an early childhood mental health consultant, it has been deeply disheartening to feel the distance that has been created between providers and parents in these circumstances, in spite of everyone’s efforts and wish to stay connected, to know and understand one another, and to work together to help children to flourish. There have at times been such limited contact between adult parties, compounding an already significant load of COVID-19–related stressors, that distrust has had much opportunity to take root. In such a situation, it seems to some degree natural that parents and providers sometimes end up feeling very alone, developing cynical views of one another, and becoming skeptical of or at odds with the other’s approach to caring for a child. Cultural differences become experienced as more pronounced and irreconcilable than before, and implicit biases can manifest in new ways and seem harder to keep in check. Holding in mind the experience and genuine, legitimate feelings of all these adults while trying to build empathy and help open lines of communication and collaboration, without generating additional work burden, has often been challenging. We on the team have clung to our conviction—our precious inheritance at the Infant-Parent Program—that tending to these relational ties is worth the effort. In the best, most successful moments, parents and providers feel seen, understood, and appreciated for their special efforts with children and experience delight, solidarity, and a renewed sense of purpose.

Ordinarily, the small but significant moments of connection between parents and caregivers during morning drop-off and afternoon pick-up form the foundations upon which an essential, trusting, rich partnership is built. Photo: Kiwi Street Studios

I am a first-generation US-born, Asian-American woman from a blended, multicultural family with roots in Hong Kong, Colombia, and the United States as well as intimate connections to many other parts of the world through the Hong Kong diaspora. I have lived in multiple regions of the United States as well as in other parts of the world. I have lived between homes, and my homes have been filled with multiple languages, including Cantonese, Mandarin, Spanish, and English. My family history is marked by stories of displacement, immigration, and existing between cultures. In the work of consultation, I have at times, and with particular individuals, made the conscious choice to share about different parts of my identity in order to explicitly acknowledge possibly shared outward and inward experiences and dilemmas. In the time of COVID-19, when anti-Asian sentiment and racist actions against Asian and Asian-American individuals have been disturbingly prevalent, there have been occasions where it has seemed important to highlight pieces of shared history and heritage in order to make room for the discussion of troubling to traumatic experiences, as well as the culturally mediated and culturally contingent ways these experiences shape the ways we feel, think, and relate with others. It has been my hope that these moments of self-disclosure and identifying with the consultee along a particular shared axis have helped build in the consultee a sense of being more deeply known and understood, and that this has enabled rich, vital, healing conversations. When we feel held by another in this way, when we feel a special connection or kinship, we often feel more open, more curious, more empathetic, and more willing to avail ourselves to others, including the parents and children whom we serve. Jeree (1995) wrote,

Everyone deserves the experience of existing in someone’s mind…It seems to me that one of life’s greatest privileges is just that—the experience of being held in someone’s mind. Possibly, though, there is one exception—and that is the privilege of holding another in one’s own. (p. 5)

Elsewhere Jeree writes about the challenges of attaining the connectedness one strives for when providing consultation via phone:

The inability to see and actually be with those to whom I was consulting was, to me, depriving and challenging… .I knew that I would sorely miss all of the facial and body expressiveness. Still, I knew I would be able to make some reasonable adaptation. …During the conference calls, I often felt a strong responsibility to clarify things as much and as quickly as I could. (Pawl, 2004, pp. 2–4)

Such frustrations and pressures have been our daily fare in recent years. Consultation by phone and video call has been a necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have leaned on Jeree’s confidence that it is possible to make “reasonable adaptations,” extending the essence of in-person consultation to the virtual formats.

Consultation by phone and video call has been a necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Photo: shutterstock/shurkin_son

For me, undertaking remote consultation during COVID-19 has meant making a special effort to connect faces to voices, such as by making constant use of photo directories, studying the names in the corner of the videoconference squares of each participant, and taking copious notes following consultation meetings in order to try to help my brain integrate these experiences with people and places. It has meant endeavoring to learn as much background as possible about individuals, teams, and programs and to observe attentively during and between meetings, including during virtual classroom observations and within phone, email, and text messaging correspondence among the various adults involved. It has meant trying to maintain as steady a meeting schedule as possible and quickly working to find another time to meet when things got in the way. It has meant being vigilant to bringing and keeping everyone on a shared conversational track when the technology or the internet connection has failed us, leading to lags, missed audio, and freezing video.

I have found that I have ended up often slowing conversations down significantly, offering a great deal of reflection, and summarizing, in order to help promote regulation but also in order to help keep everyone and everything gathered up together. Some consultees have expressly highlighted that these actions have been particularly helpful. I am aware and appreciate that all these lost milliseconds matter, that they deeply affect how we experience others and how others experience us. Someone is pulled away from the computer due to an unexpected ring at the door, or someone finds the glare in another’s glasses distracting, or someone gets frustrated because she had to repeat herself three times before the others in the group could make out what she said. These moments can lead to many small ruptures, which in aggregate can significantly compromise the sense of connectedness and with-ness that is so crucial. I can appreciate that ruptures are natural and occur frequently in even the best of relationships and during in-person interactions—and that working toward repair actually fortifies and builds resilience within relationships. It’s very possible that ruptures have been occurring at an increased frequency and in novel ways during this period and that a lot of the time we are together is spent repairing and repairing and repairing. Returning over and over again to the work of repairing can be exhausting and laborious for everyone involved. Yet attending to these relational pieces in these ways, taking these types of actions to support and tend to the relationship, is extremely important. These relationally attentive actions can be thought of as comprising both “what you do” as well as “how you are,” a way of being with, tailored and adapted and reimagined during this critical time.

Furthering the Work of Our Ancestors: Lauren’s Reflections

In an effort to ground this reflection and contextualize my voice, I will share something of “who” I am. I am a bilingual, bicultural LatinX clinician who comes from a multicultural family, a family with a history of immigration and nondominant monolingual speakers. I am a person who holds the privilege of being a documented citizen and having had the opportunity to seek higher education. It is the ancestors who paved the way for “who” I am as well as my inner sense of poder (will/ can) that enables me to engage in this reflection and speak in this voice today. Though I never met Jeree, I know that as an infant mental health person whose professional development pathway led me to the Infant-Parent Program, my learnings and my stance bring forward Jeree’s legacy, and part of what I share with others are transmissions passed from her trainees and supervisees on to me. These inherited professional pieces are stitched together with the personal, forming a unique quilt. With this quilted spirit, I enter encounters with client families, consultees, colleagues and collateral providers, and trainees alike holding an open ear and heart, listening for the ghosts (Fraiberg et al., 1975) and angels (Lieberman et al., 2005) of past and present, while creating space for such visitors in metaphor or reality.

I will briefly tell the story of my pandemic-era work with a particular family, as it illustrates aspects of the quilt and the work of quilting in the present time. As an infant–parent psychotherapist embedded in an outpatient women’s health clinic, I connect with families in the context of consultation with their providers, offer brief interventions, and sometimes engage in ongoing therapeutic intervention. In this instance, what began as a consultation with perinatal medical providers turned into ongoing dyadic work. The parent, “Mariana,” was an undocumented LatinX, monolingual Spanish-speaking, self-identified woman. Mariana was referred following a prenatal visit during which she disclosed that she had previously delivered a female infant who died within the first hour of life. She had become pregnant again shortly thereafter. As Mariana and I spent time getting to know one another by telephone at her request, she described trauma: disrupted caregiving experiences early in her life, a history of sexual assault, and significant worry about delivering a viable infant and being able to go home with that baby, all of which contributed to passive suicidal ideation. In addition, she was experiencing several psychosocial stressors and relational distress with her partner that often filled the sessions. In a trauma-informed and culturally sensitive manner, we worked to make space for the infant, while bridging and understanding how her past impacted her during this pregnancy (Lieberman et al., 2020). As we prepared for this infant’s birth, we wondered together about this infant, considered what Mariana imagined about the infant, and practiced talking directly to the infant in utero. We were attending to how Mariana was able to hold the infant she was carrying in her mind, while also grieving the infant she had lost.

In time, Mariana delivered a full-term healthy infant, “Joel,” and was able to take him home. At her request, our work continued together with Joel, who could always be heard nearby during our phone calls. One day as Mariana and I were talking, with Joel in her arms vocalizing, I said, speaking to both, “Joel, tienes muchísimo para compartir con nosotros también. (Joel, you have so much to share with us too.)” Joel continued the dialogue. Mariana responded and said to me, “Joel conoce tu voz. Creo que recuerda cuando le hablabas en mi vientre. (Joel knows your voice. I think he remembers when you would talk to him in my belly.)” Mariana then spoke to Joel: “Joel, sé que a veces me pongo triste y lloro porque extraño a tu hermana mayor, pero estoy muy feliz de que estés aquí y te amo. Lo superaremos juntos. (Joel, I know that sometimes I get sad and I cry because I miss your big sister, but I am so happy you are here and I love you. We will get through this together.)” It was in that session that I realized that, despite the pandemic conditions and our being restricted to talking exclusively by phone, Mariana had been able to take in the core transmissions of infant–parent psychotherapy: empathic validation, emotional holding, and the importance of freeing the present-day infant–parent relationship from the incumbrance of unresolved trauma, conflict, and loss in the parent’s past. All of this contributed to Mariana’s cognitive clarity, emotional strength, and empowerment to speak her truth to her infant.

Now further in my professional journey, as a reflective clinical supervisor, I find myself tending the “very special environment for teaching, created by the interaction between the supervisor and the supervisee” (1994–1995, p. 22) that Jeree described. In the course of many years of training and clinical reflective supervision, I learned the importance of moving from “safe spaces into brave spaces” (Arao & Clemens 2013), to consider diversity and social justice as key constructs in co-creating spaces for psychological and emotional holding. The hope is that supervision can become a sacred space, a space of mentorship, training, and learning, that is ultimately translated to the work with clients and their families. Jeree described the supervisory space in her 1994–1995 article on supervision as a matrix for holding the “complex nest of relationships that we must care about” (p. 23). She advocated that we all “Do unto others as [we] would have others do unto others” (p. 23), as relationships are mutually influencing. This is how I approach many relationships, remembering how parallel process presents itself within the supervisor–supervisee, supervisee– client/family, and systems–supervisor–supervisee–client/family ecological models.

Mariana was referred following a prenatal visit during which she disclosed that she had previously delivered a female infant who died within the first hour of life. Photo: shutterstock/Demkat

With all of the interwoven and intersecting relationships in mind, I think about the dance to and fro in therapeutic relationships and in training and supervision. At the Infant-Parent Program, we often discuss the various spaces for thinking and the ways that we hold traditions and one another in mind. We wonder together how we hold learners to support them in the work, and, we hope, to transmit professional identification with the work. In these ongoing conversations we continue to carry Jeree’s imperative words together wherein we are “never making difficult decisions alone” (1994–1995, p. 28). Among families and providers, between trainees and supervisors, among program clinical and administrative staff and community partners, it is juntos (together) that we are able to weave a quilt that transmits our stories and offers succor throughout the generations.

Learn More

Infant-Parent Program

Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital & Trauma Center

https://psych.ucsf.edu/zsfg/ipp

Jeree H. Pawl Memorial Fund for infant and early childhood mental health training and workforce development http://makeagift.ucsf.edu/jereepawl

Author Bios

Lauren Perez, PsyD, is a licensed clinical psychologist with the Solid Start Initiative at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital and Trauma Center (ZSFG), and the co-director of training at the Infant-Parent Program. Dr. Perez provides reflective facilitation and training; infant, perinatal, and child– parent psychotherapy; infant and early childhood mental health consultation; and perinatal mental health and reproductive justice services both within inpatient and outpatient services at ZSFG and other community settings. Dr. Perez is the liaison to the Family Treatment Court system partnered with the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. As a bilingual and bicultural Latina clinician, she provides trauma-informed and culturally responsive direct services, consultation, and reflective facilitation in both English and Spanish.

Esther Wong, LCSW, is a licensed clinical social worker who serves as an infant and early childhood mental health consultant and clinician at the Infant-Parent Program. Ms. Wong provides trauma-informed and culturally sensitive consultation to child care centers and a residential substance abuse treatment program for mothers as well as dyadic therapy services to young children and families. She has previous experience providing crisis and outpatient therapy services to children, adolescents, adults, and families in home, community, and clinic settings and providing individual, family, group, and milieu therapy for young children in early childhood education and therapeutic preschool settings.

Maria Seymour St. John, PhD, MFT, is an associate clinical professor with the University of California, San Francisco Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and co-director of training for the Infant-Parent Program. A licensed marriage and family therapist and interdisciplinary scholar, Dr. St. John’s areas of expertise include infant– parent psychotherapy, diversity and inclusion, and reflective supervision. She is a member of the faculty of the Psychoanalytic Institute of Northern California and also of the Barnard Center Advanced Clinical Training Program at the University of Washington. She is a developer of and national trainer on the Diversity-Informed Tenets for Work with Infants, Children, and Families ( http://www.diversityinformedtenets.org). Her book, Focusing on Relationships: An Effort That Pays, was published by ZERO TO THREE in 2019. She holds a psychotherapy and consultation practice in Oakland.

Suggested Citation

Perez, L., Wong, E., & St. John, S. (2022). Perspectives: Reflections from the field: Reflecting on “How you are is as important was what you do”: Jeree H. Pawl’s enduring influence in contemporary infant and early childhood mental health practice. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(4), 5– 12.

References

Arao, B., & Clemens, K. (2013) From safe space to brave spaces: A new way to frame dialogue around diversity and social justice. In L. Landreman (Ed.), The art of effective facilitation: Reflections from social justice educators (pp. 135–150). Stylus Publishing.

Celebrating the life of Jeree H. Pawl. (2021, December 18). San Francisco Chronicle. link

Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421.

Hardy, K. V., & Bobes, T. (Eds.). (2017). Promoting cultural sensitivity in supervision: A manual for practitioners. Routledge.

Hernández, P., & McDowell, T. (2010). Intersectionality, power, and relational safety in context: Key concepts in clinical supervision. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 4(1), 29–35.

Lieberman, A. F., Diaz, M. A., Castro, G., & Oliver Bucio, G. (2020). Make room for baby: Perinatal child-parent psychotherapy to repair trauma and promote attachment. Guilford Press.

Lieberman, A. F., Pardon, E., Van Horn. P., & Harris, W. W. (2005). Angels in the nursery: The intergenerational transmission of benevolent parental influences. Infant Mental Health Journal, 26, 504–520.

Noroña, C. R., Heffron, M., Grunstein, S., & Nalo, A. (2012). Broadening the scope: Next steps in reflective supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 33(2), 29–34.

Noroña, C. R., Lakatos, P. P., Wise-Kriplani, M., & Williams, M. E. (2021). Critical self-reflection and diversity-informed supervision/consultation: Deepening the DC:0–5 cultural formulation. link

Pawl, J. H. (1990). Infants in day care: Reflections on experiences, expectations and relationships. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 10(3), 1–6.

Pawl, J. H. (1994–1995). On supervision. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 15(3), 21–28. Pawl, J. H. (1995). The therapeutic relationship as human connectedness: Being held in another’s mind. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 15(4), 1–5.

Pawl, J. H. (2004). Consultation to the EHS consultants. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 24(6), 33–38.

Pawl, J. H. (2005). Perspective: Preventing expulsion from child care: How a mental health consultant helps. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 25(6), 62–67.

Pawl, J. H., & St. John, M. (1998). How you are is as important as what you do… in making a positive difference for infants, toddlers and families. ZERO TO THREE.

St. John. (2019). Focusing on relationships: An effort that pays: Parent–Child Relationship Competencies-based assessment, treatment, planning, documentation, and billing. ZERO TO THREE.