Margaret R. Beneke, University of Washington

Jennifer R. Newton, Ohio University

Meghan Vinh, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Sheresa Boone Blanchard, East Carolina University

Peggy Kemp, Division of Early Childhood, Arlington, Virginia

Abstract

The implicit and explicit messages early childhood practitioners send about disability have important consequences for young children’s developing identities and sense of belonging. The authors discuss how practitioners can cultivate early learning communities in which the identities of all young children, with and without disabilities, are affirmed. Drawing on research and examples from practice, they explain how early educators can challenge and change deficit-based assumptions about disability and other forms of diversity by practicing inclusion. The article provides a framework for practicing inclusion and illustrates how such a process has the potential to positively affect the experiences of young children with and without disabilities, sending a much-needed message to all young children and families about civil rights, human diversity, and justice.

Leo, a 2.8-year-old child, experiences developmental delays. Leo was born just months after his family emigrated from Mexico to the United States. He has attended the same early childhood center since he was 12 weeks old. Leo moved from the infant room to the toddler room alongside his peers. He frequently chooses to participate in small- and large-group classroom activities such as dancing and exploring books with other children in the class. However, center staff have recently voiced concerns about Leo advancing with his peers to the preschool classroom in the fall. The center has a strict policy that children in preschool must be able to use the bathroom independently, and Leo has not shown interest in toilet training. The staff understand that Leo’s documented developmental delays may impact when he begins toilet training. Felicia, the center director, believes her preschool staff do not have the resources to support children in diapers. Up until this point, center staff have included Leo in all classroom activities and have welcomed his early intervention (EI) team as partners in supporting full inclusion for Leo. However, when Leo’s parents meet with Felicia, the EI team, and the preschool teachers, they seem to come to an impasse over the toilet training issue.

In EI, early childhood education (ECE), and early childhood special education (ECSE) settings, the messages practitioners send about disability, identity, and belonging matter. Young children with disabilities have historically been viewed through a deficit-based lens (Seligman & Darling, 2017), which has resulted in their exclusion from educational programs (Ferri & Bacon, 2011). Exclusion comes in many forms (e.g., physical, instructional, social, representational) and can have negative consequences for young children’s sense of self (Rutland & Killen, 2015), sense of belonging (Favazza, Ostrosky, Meyer, Yu, & Mouzourou, 2017; Nind, Flewitt, & Payler, 2010), and sense of fairness (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2011). What is more, hateful and exclusionary language and images related to disability and other historically marginalized identities have increased during and following the 2016 U.S. presidential election (Costello, 2016), further impacting young children’s sense of identity, belonging, and fairness. Therefore, there is an urgent need for early childhood practitioners to think critically about the practices they use to support inclusion.

While the need for inclusion in early childhood is urgent, practitioners’ knowledge and skills to support young children with disabilities may vary. Differences in training based on early education professional roles (i.e., EI, ECE, ECSE; Horm, Hyson, & Winton, 2013) and discrepancies in professional experiences based on early childhood settings (e.g., home-based services and programs, public center-based services and programs, private center-based services and programs; Fuligni, Howes, Huang, Hong, & Lara-Cinisomo, 2012), may result in an uneven knowledge base regarding how to include young children with disabilities in early learning settings (Sutherland & Teacher, 2004). Such variation means that EI/EC/ECSE practitioners enter the work of inclusion with a range of experiences and vantage points, requiring professional support (e.g., resources, professional development) in different forms, frequencies, and levels of depth.

Despite professional variation in knowledge and skills, we argue here that all early childhood practitioners have the responsibility to cultivate early learning communities in which the identities of all young children are affirmed (Ferri & Bacon, 2011). There-fore, practitioners must be supported to learn about inclusion, challenge and change deficit-based assumptions about disability and other forms of diversity, engage in processes of reflection, and take actions that allow all young children to fully participate in their communities. Practicing inclusion is not easy. Despite more than 40 years of research, advocacy, and policy work documenting the important benefits of inclusion for all children, too many young children with disabilities continue to be excluded from meaningful learning opportunities with their same-age peers (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education, 2015). For this reason, the Division for Early Childhood Priority Issues Agenda (2018) included “(Actually Achieving) High Quality Inclusion” as a priority for all professionals that support young children and their families (p. 2). In this article, we discuss this professional priority in depth by offering definitions, perspectives, strategies, and resources for practicing inclusion and doing justice in early childhood settings.

Key Terms and Definitions: Disability, Ableism, Inclusion

To frame our discussion on supporting identity and belonging for young children with and without disabilities in EI/ECE/ECSE, we begin with some key terms and definitions.

What Is Disability?

A variety of terms have been used to describe young children, like Leo, who receive EI or ECSE services through the Individuals With Disabilities in Education Act (IDEA; Hebbeler, Spiker, & Kahn, 2012), including “children with special needs” (Cook, Klein, & Chen, 2015; Sukkar, Dunst, & Kirkby, 2017) and “children with developmental delays or disabilities” (Bruder, 2010; Sullivan-Sego, Ro, & Park, 2016). We explicitly avoid the use of euphemisms (e.g., diff-abilities, special needs, special rights), which have shown to be ineffective in reducing stigma associated with disability (Gernsbacher, Raimond, Balinghasay, & Boston, 2016), and which disability rights advocates and individuals in disability communities argue often perpetuate deficit-based assumptions and exclusionary educational practices (Back, Keys, McMahon, & O’Neill, 2016; Rutherford, 2016). Instead, we purposefully use the terms “developmental delay” and “disability,” to be clear about our point of reference, and to connect our discussion to federal language in IDEA.

In the context of EI/ECE/ECSE settings, young children like Leo may receive disability labels (e.g., developmental delay, intellectual disability, visual impairment) that grant them and their families EI or ECSE services or both. For the purposes of this article, we highlight how these labels act as identity markers that have real consequences. Our goal is not to minimize the lived reality of young children and families who receive these labels, or to dismiss the important role they play in supporting access to EI/ECSE services. Instead, we draw attention to how notions of ability “difference” are constructed in relation to implicit assumptions about normalcy (Annamma, Connor, & Ferri, 2016). In other words, disability is produced in environments in which individuals are perceived to be different from socially constructed notions of normal child development. For example, in the opening vignette, Leo’s delay in toilet training was constructed in relation to a socially shared value around when and how toilet training should be mastered. Were Leo to be in a program with different expectations for toilet training, there may have been no issue with him transitioning to preschool. Thus, despite the ways IDEA frames disability as an either/or (i.e., an individual either has a disability label or does not), the meanings and consequences of a disability label change depending on children’s circumstances, and directly relate to assumptions in particular social environments (e.g., classrooms, child care centers, schools).

As we discuss identity and belonging in EI/ECE/ECSE, we recognize that disability identity is complex and intersects with other aspects of identity. By this we mean, there is a tendency to discuss individuals in terms of singular notions of identity (i.e., disability or race or gender) and to make generalizations about all people within these categories. However, we know that individuals with disabilities are simultaneously members of multiple identity groups and social locations (Annamma et al., 2016; Crenshaw, 1995; Gillborn, 2015), whose experiences with disability, identity, and belonging vary. For instance, Leo is not only a young child with a developmental delay, but also a young boy of color whose parents are immigrants. Based on a combination of factors (i.e., biological, environmental, geographic, historical, political), Leo’s sense of self and belonging may look very different from another child with the same disability label. In this article, while we foreground disability, we recognize how intersecting identity markers (e.g., race, gender, class, language) are also relevant to a child’s sense of self and belonging.

Early educators who practice inclusion design and reflect on activities, environments, and classroom experiences with each individual learner in mind, to ensure that all children can access and participate in interesting, relevant, and engaging early learning experiences. Photo: Copyright © ZERO TO THREE

What Is Abelism?

Leo’s parents worry about the short-term and long-term consequences of not advancing Leo to the preschool classroom with his peers and feel that the center is not considering Leo’s identity and sense of belonging. They are concerned that center staff are focused on what Leo cannot do rather than all that he can do. They are afraid that keeping Leo in the toddler classroom will affect his friendships while sending other children, families, and center staff deficit-based messages about Leo, his disability, and their family. At drop off, Leo’s mother has already heard another child call Leo a “baby,” because he still “wears diapers” and is upset that the teachers did not intervene. Leo’s father wonders how their family’s immigration status might also be impacting center staff’s thinking about Leo’s transition.

Supporting young children with and without disabilities to navigate messages about their own and others’ identities requires that EI/ECE/ECSE practitioners contend with implicit and explicit forms of ableism. Like other -isms (e.g., racism, sexism), ableism is an oppressive ideology that permeates systems, policies, and practices. Ableism can be understood as:

The devaluation of disability [that] results in societal attitudes that uncritically assert that it is better for a child to walk than roll, speak than sign, read print than read Braille, spell independently than use a spell-check (Hehir, 2002, p. 3).

Ableism is systemic, meaning it is not simply an individually held explicit prejudice, but a social idea that is deeply embedded in how society is structured around singular accepted standards of physical, intellectual, and emotional normalcy (Sensoy & DiAngelo, 2017). Such enmeshed societal attitudes mean that even well-intentioned EI/ECE/ECSE educators work in systems that frame young children who do not meet notions of “normalcy” through a deficit lens (Ferri & Bacon, 2011). To illustrate, Leo is seen as “different” from his same-age peers because he is not meeting center staff’s developmental expectations for toilet training. Because of this difference, the problem is seen as “with Leo” versus with staff expectations or the policy. Positioning Leo as the problem justifies his potential exclusion from transitioning to preschool, as opposed to critically examining programmatic expectations for toilet training. In addition, Leo’s father is concerned that this decision is potentially influenced not only by ableism but also by deficit-based thinking toward children of immigrants. Leo’s father’s response is justified, as ableism can be exacerbated when individuals experience intersectional forms of oppression (i.e., ableism and xenophobia; Annamma et al., 2016).

To promote young children’s sense of belonging, EI/EC/ECSE educators must recognize how ableism operates through deficit-based thinking and take actions that support children’s belonging in classroom and program communities. First, center staff can shift the focus to children’s assets and interests. Instead of concentrating on a narrow set of skills (e.g., toilet training) that Leo does not have to be “ready” for the transition to preschool, staff can prioritize ensuring the classroom and program are ready for Leo. Thinking through the underlying goals and objectives of toilet training is one place to start. If the center’s goal for toilet training is to streamline routines for adults, staff should instead be supported to adjust aspects of the classroom schedule, staffing patterns, physical environment, or a combination of these, to ensure that all children can participate. If the classroom goal for toilet training is to support children’s developing body awareness, staff might first ask Leo’s family and his EI team whether this is a goal they value or think is appropriate. Staff might consider the extent to which Leo can continue to practice body awareness in other activities throughout the classroom based on his interests. Leo has already demonstrated enthusiasm for dancing with his peers. Therefore, dancing might provide an entry point for Leo’s teachers to support Leo’s developing body awareness (e.g., “Let’s spin and wave our arms;” “Can you stop when the music stops?”). Moreover, staff might communicate with Leo’s family about his eagerness to participate in classroom dancing and ask whether Leo dances at home, perhaps even inviting Leo’s family to share favorite dance music with the entire class. Taken together, these examples illustrate how EI/EC/ECSE educators might resist ableism and promote all children’s belonging.

Ableism is also learned. As young children traverse complex worlds in which some individuals are often implicitly seen from a deficit lens based on ability differences, they learn to negotiate these ideologies (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2011). When young children enter environments outside of home, they encounter new messages about their own abilities and those of others (Ostrosky, Mouzourou, Dorsey, Favazza, & Leboeuf, 2015). For instance, a content analysis of children’s literature revealed that the majority of picture books published in 2012 for young children featured able-bodied (i.e., physically, intellectually, and emotionally “competent”) characters (Koss, 2015), sending a message that to be able-bodied is normal. Devoid of opportunities to explore these topics, young children are likely to draw conclusions based on implicit messages they perceive through taken-for-granted social processes in their environments (Jones, 2004), including internalizing ableist messages about themselves and others (Kattari, Olzman, & Hanna, 2018). Indeed, young children can develop prejudicial attitudes and exclusionary social behaviors toward peers with disabilities (Diamond & Tu, 2009; Yu, Ostrosky, & Fowler, 2012). In Leo’s case, when another child in his class assumed he was a “baby” because he still wore diapers, Leo’s teachers did nothing to probe the child’s thinking or counter deficit-based thinking. Yet, this was an important opportunity for Leo’s teacher to understand how Leo and his peers interpret ability differences, affirm Leo’s identity, and re-frame meanings of disability for his peers. This was also an opportunity for Leo’s teacher to critically reflect on the language classroom staff use with children in the class to discuss toilet training in relation to age (e.g., “You are wearing big kid underpants!” “Look at you, going to the toilet like a big kid!”). While disability can be a source of joy and solidarity (Schalk, 2013), this is rarely the explicit messaging young children receive.

To gain additional meaning about this child’s comment, Leo’s teacher could have asked, “What do you mean by that?” Leo’s teacher could have followed up with a clear statement about Leo’s age and getting help in the classroom, stating, “Leo is not a baby. He is the same age as you! We all need help with different things in our classroom, and we are all important members of this community. Leo’s diapers will help him stay dry until he wants to try to use the toilet. What are some ways you get help in our classroom?” Such a response from the teacher could communicate Leo’s role as a valuable member of the community and signal that the classroom is one that embraces every individual’s needs. Moreover, responding in this way could allow for continued classroom conversations about the different supports each individual uses to accomplish tasks and the value of supporting one another in community.

What Is Inclusion?

A traditional definition of inclusion emerged in the US in response to a history of children with disabilities being excluded from educational experiences with typically developing peers, being denied access to the general education curriculum, and being educated in programs with little or no accountability (Ferri & Connor, 2005). Traditional inclusion, then, often refers to the placement and service of all children, with and without disabilities, in educational settings (Guralnick & Bruder, 2016), to strengthen children’s participation, social relationships, and learning outcomes (Division for Early Childhood & National Association for the Education of Young Children, 2009; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education, 2015). Indeed, decades of research indicate that inclusion leads to social, cognitive, and academic benefits for young children with and without disabilities (National Professional Development Center on Inclusion, 2009; Odom, Buysse, & Soukakou, 2011). A traditional view of inclusion aims to support all young children in EI/ECE/ECSE settings through thoughtful accommodations and supports.

Simultaneously, scholars offer a transformative definition of “inclusive education,” (Allan, 2003 ; Artiles, Kozleski, & Waitoller, 2011), conceptualized as an ongoing process in response to the exclusion of children viewed by educational systems as different (e.g., children with disabilities, children of color, children who are dual language learners) from socially constructed normative standards (e.g., children who are typically developing, children who are White, children whose home language is English). A transformative view of inclusion also aims to support all children in the classroom (Ashby, 2012 ), by asking “Who does not have access and why do we think that is?” When conceptualized this way, inclusion promotes justice through ongoing attention, reflection, and action toward understanding how historically marginalized young children can more equitably participate in early educational processes and communities.

We draw on both traditional and transformative views of inclusion in our discussion of EI/ECE/ECSE practices that can support belonging for young children with disabilities. Early educators who practice inclusion design and reflect on activities, environments, and classroom experiences with each individual learner in mind, to ensure that all children can access and participate in interesting, relevant, and engaging early learning experiences. For example, early educators in a toddler classroom might post simple step-by-step photographs of children engaging in classroom transition to the outdoors so that children see themselves represented in the classroom and have visual cues to support the transition process. These same educators might engage in ongoing documentation of children’s interests and home experiences, rotating available choices to ensure that activities will garner each child’s interests. Educators might build classroom systems for multiple modes of communication, in which children can express their feelings verbally and/or by pointing to pre-printed images. In the next section, we discuss the process of practicing inclusion and doing justice in more depth, using Leo’s story as an example.

Practicing Inclusion

The meeting to discuss Leo’s toilet training and potential transition to preschool continues. One member of Leo’s EI team, Dana, speaks up, “I think it’s important to consider the ramifications of keeping Leo in the toddler room. This decision means we are excluding Leo from preschool. How will this decision affect Leo and how he feels about himself? How will it influence how his peers think and feel about him? We are keeping Leo from important learning opportunities and friendships in the name of toilet training. Can we think creatively about how to work around this toilet training policy?”

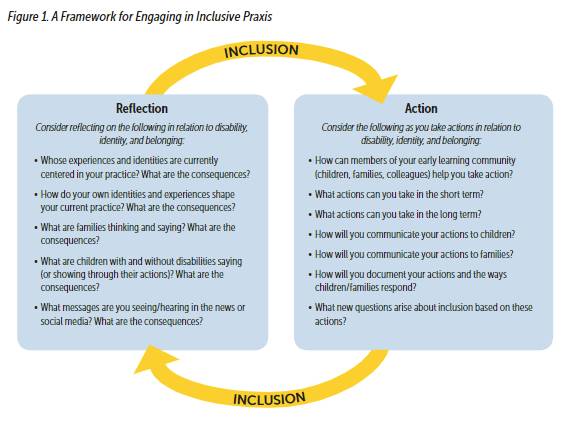

In the context of histories of educational exclusion and deficit-based narratives about disability, EI/ECE/ECSE practitioners must grapple with how ableism shows up in their day-to-day practice, as well as in program policies and procedures. While adapting practice to meet the needs of individual children and families is necessary, it is equally important to re-think policies that perpetuate exclusion. Doing so supports and affirms the identities of young children with disabilities in early educational settings. Critically interrogating assumptions to promote belonging can be accomplished through praxis. As Freire (2018) explained, “Praxis [is] reflection and action on the world in order to transform it” (p. 51). We apply this view of praxis to inclusion (see Figure 1). Through an ongoing, iterative process of reflection and action, we believe EI/ECE/ECSE practitioners can practice inclusion, transforming early learning communities into spaces where young children with and without disabilities are seen as valuable not in spite of their differences, but because of them.

Reflection

After Dana’s remark, the meeting room is quiet for a moment. Felicia responds first, “Wow. I hadn’t thought about it this way. Your comment really made me think about the messages we are sending all the children, including Leo. The toilet training policy was established to promote independence in preschool and to satisfy licensure regulations, but I don’t want the children to learn that exclusion is okay.” Kevin, one of the preschool teachers, jumps in, “Okay, but we still have some practical barriers to overcome. The preschool room doesn’t have a changing table, and we will have to think about staffing during toileting times.” Leo’s mom, Camila, responds, “Felicia, I appreciate your thoughtful reflection—this is such a relief to hear.” Camila turns to the EI team, “Dana, do you have thoughts around how Kevin and the preschool team could think through this issue?”

For EI/ECE/ECSE practitioners, an important step in practicing inclusion for young children with and without disabilities is recognizing how early education policies and practices have consequences beyond particular outcomes. For instance, per Felicia’s interpretation, the original intent of the toilet training policy had been to support young children’s development of independence and to satisfy child care center licensure requirements, but the staff had not considered the consequences of the policy in terms of identity and belonging. Engaging in inclusive praxis requires educators to consider how they can use their positions of authority to practice inclusion and do justice (Lake, 2016). In EI/ECE/ECSE settings, practitioners need to reflect on how their own positions, identities, and experiences shape their practice, listen carefully to children and families in their early learning communities, and consider the consequences in terms of disability identity and belonging. See Figure 1 for a list of suggested questions to guide initial reflection.

Action

The team decides to look at the preschool toileting space together. As they walk to the classroom, Felicia, Dana, and Camila talk about Leo’s development. As Camila looks at the toilet she says, “You know, I am not sure toilet training is even a concern for our family right now. Leo has been working so hard to verbally communicate his feelings, and we have really been putting our energy into supporting him with that. I’m not saying he won’t ever be toilet-trained, but right now we want to follow his lead.” Felicia and Dana listen as Camila shares her perspective, and they rethink priorities for Leo. By the time they join the rest of the team in the preschool bathroom, they are beginning to form a plan. Kevin reiterates the lack of space for a changing table. Dana turns to Felicia, “Maybe we could move this cabinet into the prekindergarten room and make space for a changing table here.” Felicia makes a note that she will call the child care licensing office about the change. Camila feels now is a safe time to push the conversation further, “You know, I heard one of Leo’s peers call him a ‘baby’ the other day because he wears diapers. How will you all address this now?” As the team begins measuring the space, Kevin reflects aloud, “I wonder how we can involve Leo and his peers in thinking about disability, identity, and fairness? This seems like a great opportunity to introduce early concepts of equity.”

Inclusion promotes justice through understanding how historically marginalized young children can more equitably participate in early educational processes and communities. Photo: Copyright © ZERO TO THREE

In taking action, it is important to gather input from multiple perspectives. For example, without listening to Camila’s perspective, Felicia and Dana may assume toilet training is a priority for Leo and his family. Taking action as a team leads Kevin to reflect on how he might engage children, including Leo, in classroom conversations about disability and identity. Involving children and families in this process allows early educators to consider implicit messages they are sending about inclusion and belonging in their particular contexts. Moreover, even very young children can participate in explicit conversations about supporting positive identities of all children and can take actions to advance equity (Derman-Sparks & Edwards, 2011; Kuh, LeeKeenan, Given, & Beneke, 2016; LeeKeenan & Allen, 2017). See Figure 1 for a list of suggested questions to guide practitioners in taking action.

Conclusion

As the meeting wraps up, Felicia says to the group, “This has been such an eye-opening experience for me. I have always believed our center was inclusive, and now I am reflecting on the many ways we may be unintentionally excluding kids in terms of learning opportunities, social experiences with peers, and materials in the classroom…I’d like to start a committee of parents and teachers to continue breaking down these barriers.” Camila responds, “I would love to be a part of that committee. It would be interesting to see how we could involve the children in this work as well. Let me know how I can help.” Kevin, who had initially articulated feeling unprepared to include Leo, shares,“This conversation has pushed me in ways I was not expecting. I’m looking forward to learning more about how to make this an awesome year for Leo, for you all, and for the preschool children.”

Cultivating early learning communities in which the identities of all young children are supported and affirmed is an iterative, ongoing process. Photo: Africa Studio/shutterstock

Cultivating early learning communities in which the identities of all young children are supported and affirmed is an iterative, ongoing process. Said differently, inclusive praxis requires early educators to engage in a reciprocal cycle of reflection and action. Because center staff took time to rethink the policy and have begun to shift practice, Leo now has the opportunity to continue building relationships with his peers and learn alongside his peers in preschool. The adults in Leo’s early learning community worked together to engage in reflection and action around the toilet training policy, and this process must continue for Leo to be supported once he enters the preschool classroom. Therefore, practicing inclusion in EI/ECE/ECSE settings is never over. Inclusive praxis requires that early educators continue to challenge deficit-based assumptions about disability and other forms of diversity, recognize how forms of exclusion present in their practice, and make changes. Through ongoing reflection and action, EI/EC/ECSE educators can consider how classroom and program policies, activities, experiences, and environments allow every child to access and participate in meaningful learning. This process can support children with disabilities, like Leo, to build a positive sense of self and experience belonging. Ultimately, such a process has the potential to positively affect the experiences of young children with and without disabilities, sending a much-needed message to all young children and families about civil rights, human diversity, and justice.

Authors’ Note

The authors of this article represent former early educators, local and state administrators, professional development, current EI/ECE/ECSE scholars, and representatives of the Division for Early Childhood (DEC). DEC promotes policies and advances evidence-based practices that support families and enhance the optimal development of young children (birth to 8 years old) who have or are at risk for developmental delays and disabilities. DEC is an international membership organization for those who work with or on behalf of young children (birth to 8 years old) with disabilities and their families. www.dec-sped.org

Learn More

Resources for Practicing Inclusion in Early Childhood Settings

The Preschool Inclusion Toolbox: How to Build and Lead a High-Quality Program

E. E. Barton & B. J. Smith (2015)

Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Implementing the Project Approach in Inclusive Early Childhood Classrooms

S. Beneke, M. M. Ostrosky, & L. G. Katz (2018)

Baltimore, MD: Brookes

DEC Recommended Practices in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education 2014

Division for Early Childhood (2014)

www.dec-sped.org/recommendedpractices

First Steps to Preschool Inclusion

S. S. Gupta, W. R. Henninger, & M. E. Vinh (2014)

Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Six Steps to Inclusive Preschool Curriculum: A UDL-Based Framework for Children’s School Success

E. M. Horn, S. B. Palmer, G. D. Butera, J. A. Lieber, A. I. Classen, J. Clay, … A. Mihai (2016)

Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Authors

Margaret R. Beneke, PhD, is an assistant professor in the College of Education at the University of Washington. A former inclusive early childhood teacher, Dr. Beneke completed her doctoral degree in special education at the University of Kansas. Her scholarship focuses on increasing access for children and families from historically marginalized backgrounds to inclusive, equitable education. Through critical analysis of the local processes and consequences of identity construction (e.g., ability, race, gender), she aims to support early childhood practitioners’ inclusive practices, as well as identify and transform deficit discourses surrounding young children’s identities and competencies. Dr. Beneke received the 2018 Outstanding Dissertation Award from the American Educational Research Association Disability Studies in Education Special Interest Group. She currently serves as managing editor for the Division for Early Childhood’s practitioner journal, Young Exceptional Children.

Jennifer R. Newton, PhD, is an assistant professor of early childhood special education in the Department of Teacher Education at Ohio University. Prior to earning a doctorate in special education at the University of Kansas, she served as an early interventionist, inclusive prekindergarten teacher, and family educator in North Carolina. Dr. Newton’s research interests include strengths-based approaches to families, early childhood inclusion and equity, and inclusive teacher preparation. She regularly presents locally, regionally, and nationally on these topics. Dr. Newton serves as a co-chair of the Division of Early Childhood’s Inclusion, Social Justice, and Equity Committee nationally, in addition to her active service in local and state leadership roles.

Megan Vinh, PhD, is an advanced technical assistance specialist at the Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill. Dr. Vinh currently serves as the co-principal investigator of the Early Childhood Technical Assistance project, the co-principal investigator of the Early Childhood Recommended Practice Modules project, and the evaluation lead for the Center for IDEA Early Childhood Data Systems. In her role, she provides leadership, technical assistance, and evaluation support around improving state early intervention and early childhood special education service systems, increasing the implementation of effective practices, and enhancing outcomes of these programs for young children and their families. She specializes in program evaluation and systems change around access and equity issues, including reducing early care and education suspensions and expulsions and increasing high-quality inclusive opportunities. Dr. Vinh also serves as president-elect of the Division for Early Childhood Executive Board.

Sheresa Boone Blanchard, PhD, is an assistant professor in birth through kindergarten at East Carolina University in the Department of Human Development and Family Science. Her research and teaching focus on family/community engagement, cultural reciprocity, and improving teacher preparation competencies through the lenses of intersectionality, equity, diversity, and social justice. Dr. Blanchard’s scholarly interests emerged from her 10 years of experience as a practitioner and consultant in early childhood, special education, and early intervention. She received her doctoral degree in specialized education services from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Dr. Blanchard currently serves as a member of the North Carolina Early Childhood Foundation board and co-chairs the Division for Early Childhood’s Inclusion, Equity, and Social Justice Committee. She is actively engaged with North Carolina’s early intervention systemic improvement efforts, as well as other local, regional, and national early childhood initiatives.

Peggy Kemp, PhD, is the executive director of the Division for Early Childhood (DEC). Dr. Kemp is a recognized leader and tireless advocate devoted to quality services for families of young children with disabilities and the professionals who serve them. She guides DEC’s strategic direction and oversees daily operations. Dr. Kemp has experience as a direct service provider as well as a local, state, and national leader. She holds a doctorate in special education from the University of Kansas. Dr. Kemp has received a number of honors throughout her career, including the 2008 Kansas Division for Early Childhood Award for Significant Contributions in Leadership, Service and Advocacy. Her life experiences as a family member of persons with disabilities fuels her passion to support policies that enhance the lives of families.

Suggested Citation

Beneke, M. R., Newton, J. R., Vinh, M., Blanchard, S. B., & Kemp, P. (2019). Practicing inclusion, doing justice: Disability, identity, and belonging in early childhood. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(3), 26–34.

References

Allan, J. (2003). Inclusion, participation and democracy: What is the purpose? Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2016). Touchstone text: Disability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and disa/bility. In D. Connor, B. Ferri, & S. A. Annamma (Eds.), DisCrit: Disability studies and critical race theory in education (pp. 9–34). New York, NY: Teachers College.

Artiles, A. J., Kozleski, E. B., & Waitoller, F. R. (Eds.). (2011). Inclusive education: Examining equity on five continents. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Ashby, C. (2012). Disability studies and inclusive teacher preparation: A socially just path for teacher education. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities,37(2), 89–99.

Back, L. T., Keys, C. B., McMahon, S. D., & O’Neill, K. (2016). How we label students with disabilities: A framework of language use in an urban school district in the United States. Disability Studies Quarterly, 36(4). Source

Bruder, M. B. (2010). Early childhood intervention: A promise to children and families for their future. Exceptional Children, 76(3), 339–355.

Cook, R. E., Klein, M. D., & Chen, D. (2015). Adapting early childhood curricula for children with special needs (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Costello, M. (2016). The Trump effect: The impact of the 2016 presidential election on our nation’s schools. Teaching Tolerance. Source

Crenshaw, K. W. (1995). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In K. Crenshaw, N. Gotanda, G. Peller, & K. Thomas (Eds.), Critical race theory: The key writings that formed the movement (pp. 357–383). New York, NY: New Press.

Derman-Sparks, L., & Edwards, J. O. (2011). Anti-bias education for young children and ourselves. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Diamond, K., & Tu, H. (2009). Relations between classroom context, physical disability and preschool children’s inclusion decisions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(2), 75–81.

Division for Early Childhood. (2018). DEC priority issues agenda. Source

Division for Early Childhood & National Association for the Education of Young Children. (2009). Early childhood inclusion: A joint position statement of the Division for Early Childhood and the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Source

Favazza, P. C., Ostrosky, M. M., Meyer, L. E., Yu, S., & Mouzourou, C. (2017). Limited representation of individuals with disabilities in early childhood classes: Alarming or status quo? International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(6), 650–666.

Ferri, B. A., & Bacon, J. (2011). Beyond inclusion: Disability studies in early childhood teacher education. In B. Fennimore & A. Lin Goodwin (Eds.), Promoting social justice for young children (pp. 137–146). New York, NY: Springer.

Ferri, B. A., & Connor, D. J. (2005). Tools of exclusion: Race, disability, and (re) segregated education. Teachers College Record, 107(3), 453–474.

Freire, P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed (50th anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Fuligni, A. S., Howes, C., Huang, Y., Hong, S. S., & Lara-Cinisomo, S. (2012). Activity settings and daily routines in preschool classrooms: Diverse experiences in early learning settings for low-income children. Early childhood research quarterly, 27(2), 198–209.

Gernsbacher, M. A., Raimond, A. R., Balinghasay, M. T., & Boston, J. S. (2016). “Special needs” is an ineffective euphemism. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 1(29). Source

Gillborn, D. (2015). Intersectionality, critical race theory, and the primacy of racism: Race, class, gender, and disability in education. Qualitative Inquiry, 21(3), 277–287.

Guralnick, M. J., & Bruder, M. B. (2016). Early childhood inclusion in the United States: Goals, current status, and future directions. Infants & Young Children, 29(3), 166–177.

Hebbeler, K., Spiker, D., & Kahn, L. (2012). Individuals With Disabilities Education Act’s early childhood programs: Powerful vision and pesky details. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(4), 199–207.

Hehir, T. (2002). Eliminating ableism in education. Harvard Educational Review, 72(1), 1–33.

Horm, D. M., Hyson, M., & Winton, P. J. (2013). Research on early childhood teacher education: Evidence from three domains and recommendations for moving forward. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 34(1), 95–112.

Jones, H. (2004). A research-based approach on teaching to diversity. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31(1), 12–19.

Kattari, S. K., Olzman, M., & Hanna, M. D. (2018). “You look fine!” Ableist experiences by people with invisible disabilities. Affilia. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0886109918778073

Koss, M. D. (2015). Diversity in contemporary picturebooks: A content analysis. Journal of Children’s Literature, 41(1), 32–42.

Kuh, L. P., LeeKeenan, D., Given, H., & Beneke, M. R. (2016). Moving beyond anti-bias activities: Supporting the development of anti-bias practices. Young Children, 71(1), 58–65.

Lake, R. L. (2016). Radical love in teacher education praxis: Imagining the real through listening to diverse student voices. The International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 7(3), 79–98.

LeeKeenan, D., & Allen, B. (2017). It can be done! Strategies for embedding anti-bias education into daily programming. Child Care Exchange, July/August. Source

National Professional Development Center on Inclusion, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, The University of North Carolina. (2009). Research synthesis points on early childhood inclusion. Source

Nind, M., Flewitt, R., & Payler, J. (2010). The social experience of early childhood for children with learning disabilities: Inclusion, competence and agency. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 31(6), 653–670.

Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33(4), 344–356.

Ostrosky, M. M., Mouzourou, C., Dorsey, E. A., Favazza, P. C., & Leboeuf, L. M. (2015). Pick a book, any book: Using children’s books to support positive attitudes toward peers with disabilities. Young Exceptional Children, 18(1), 30–43.

Rutherford, G. (2016). Questioning special needs-ism: Supporting student teachers in troubling and transforming understandings of human worth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 127–137.

Rutland, A., & Killen, M. (2015). A developmental science approach to reducing prejudice and social exclusion: Intergroup processes, social-cognitive development, and moral reasoning. Social Issues and Policy Review, 9(1), 121–154.

Schalk, S. (2013). Coming to claim crip: Disidentification with/in disability studies. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(2). Source

Seligman, M., & Darling, R. B. (2017). Ordinary families, special children: A systems approach to childhood disability (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Sensoy, O., & DiAngelo, R. (2017). Is everyone really equal?: An introduction to key concepts in social justice education (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Sukkar, H., Dunst, C. J., & Kirkby, J. (Eds.). (2017). Early childhood intervention: Working with families of young children with special needs. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sullivan-Sego, C., Ro, Y., & Park, J. (2016). Including all learners with diverse abilities. Childhood Education, 92(2), 134–139.

Sutherland, C., & Teacher, S. (2004). Attitudes toward inclusion: Knowledge vs. experience. Education, 125(2), 163–172.

U. S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Policy statement on inclusion of children with disabilities in early childhood programs. Source

Yu, S., Ostrosky, M. M., & Fowler, S. A. (2012). Measuring young children’s attitudes toward peers with disabilities: Highlights from the research. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 32(3), 132–142.