Kristen Schraml-Block and Michaelene M. Ostrosky, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Abstract

Early interventionists interact and partner with a multitude of families, all with unique strengths, backgrounds, and circumstances. During partnerships with family members, professionals may encounter interactions and relationships that they perceive as challenging or imbalanced. Skilled Dialogue is a framework which emphasizes the use of respectful, reciprocal, and responsive interactions with families from diverse backgrounds (Barrera & Corso, 2002). Early intervention professionals may consider this framework and the supporting strategies to strengthen their partnerships with families.

Michelle had her second child, Isabella, 6 months ago. However, Michelle received some unexpected news at the hospital before bringing Isabella home—she has Down syndrome. Subsequently, Isabella and Michelle were referred to their local early intervention (EI) program for an evaluation. After the family was found eligible for services, the EI team developed an Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP), which included a plan for how EI services could support the family’s priorities for Isabella. Since Isabella’s birth, Michelle experienced a range of emotions—from pure joy when interacting with Isabella to disbelief about her diagnosis. Michelle was often overwhelmed with uncertainty regarding Isabella’s disability and its impact on her development and future. In between feelings of isolation and uncertainty, Michelle was elated to be Isabella’s mother and was committed to being the best possible caregiver to her daughter.

Since the inception of Part C programs (formerly known as Part H) in 1986, one of the main goals of this federal legislation has been to enhance the capacity of families to meet the needs of their young children with disabilities or developmental delays (Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986, §671(a)(4)(1986)). One way to achieve this goal is through the implementation of the Division of Early Childhood’s (DEC) Recommended Practices (DEC, 2014). DEC’s recommended practices consist of seven different domains (i.e., assessment, environment, family, instruction, interaction, teaming and collaboration, and transition), and several practices to support each domain. The purpose of DEC’s recommended practices is to bridge the research-to-practice gap, thereby enhancing the development of young children with delays and disabilities. The family domain emphasizes the importance of family involvement in the EI/early childhood process and supports the use of family-centered and family-capacity building practices, as well as family-professional collaboration. This domain includes several practices such as a) respectful, collaborative partnerships; b) sensitive interactions that are responsive to families’ unique circumstances; c) individualized services based on families’ priorities, cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic diversity; and d) capacity-building practices that strengthen parental knowledge and skills (DEC, 2014).

Robyn, the early interventionist assigned to partner with Michelle and Isabella, has begun to provide services around the family’s IFSP outcomes. During each visit, Robyn attempts to engage Michelle in conversations about Isabella’s progress, as well as about routines and strategies that are working to support Isabella. However, Robyn notices that Michelle seems to “shut down” during these conversations. Michelle looks away and even gets up from the conversations to do things such as wash dishes or make phone calls. After just a few sessions, Robyn is beginning to wonder whether she is welcome in the home or whether the family prioritizes the services that EI offers. For example, when Robyn arrives for one EI visit, which she confirmed with Michelle 24 hours ahead of time, no one answers the door. Robyn immediately asks herself, “Why has it been so challenging to partner with this caregiver? Why do our conversations seem so guarded and unnatural? What can I do to better connect with this family?”

Early interventionists may wonder how to implement recom-mended practices and provide family-centered care when caregivers do not participate in the ways that one might hope or that align with recommended practices. EI providers, like Robyn, may find themselves questioning how they can better connect with caregivers, form partnerships with families, or even broach difficult topics. The technique of Skilled Dialogue provides early interventionists with a framework and supporting strategies to consider when forming and sustaining partner-ships with caregivers in EI, especially when navigating topics or conversations that might be perceived as uncomfortable or difficult.

Skilled Dialogue

Skilled Dialogue (Barrera & Kramer, 2012) can be a useful approach when conversational partners have different opinions about an issue or when they are simply exploring differences together. The strategies within the Skilled Dialogue framework align with recommended practices in EI. Robyn is eager to partner and collaborate with Michelle and Isabella, but Michelle does not seem as eager to engage in conversations that focus on her daughter. It appears that there are clear differences between Robyn’s and Michelle’s perceptions of the EI process.

Respect, Reciprocity, and Responsiveness

There are three important qualities that support the use of Skilled Dialogue: (a) respect, (b) reciprocity, and ( c) responsiveness. Respect, according to this framework and within the context of EI, involves the acknowledgement of differences that exist between caregivers and professionals. Practitioners demonstrate respect for caregivers’ experiences, perceptions, and opinions by acknowledging differences and allowing those differences to simply be, without necessarily aligning caregivers’ experiences, opinions, and perceptions with their own (Barrera & Kramer, 2012).

For example, Robyn shows respect for Michelle by acknowledging her as a single, first-time mother of a child with a disability, who wants the best for her daughter. In addition, it is critical for Robyn to acknowledge that Michelle’s perceptions regarding EI and their roles in the process may be different from her own.

The second characteristic, reciprocity, involves acknowledging that caregivers, regardless of how different their backgrounds and experiences are from those of the professional, have just as much to contribute to the relationship as professionals believe that they do (Barrera & Kramer, 2012). Lyon and Lyon (1980) defined role release as a means of sharing information and skills between two individuals (as cited in McCollum & Hughes, 1998). Within the context of EI, role release might mean that Robyn shares the power, information, and skills with Michelle instead of being the “expert.” While professionals have a specialized set of skills that can help them support and guide caregivers, families ultimately know their children best (Bruder, 2000; Keilty, 2017). If professionals ascribe to this belief, they will recognize all the ways that families contribute to the development of their own children and the family-EI partnership. Therefore, true reciprocity means believing that everyone has something to share and contribute. According to Barrera, Corso, and Macpherson (2003), “reciprocity enriches not only the persons involved, but also the outcome of their interactions” (p. 46).

Within the context of the vignette, reciprocity means that Robyn believes Michelle has significant contributions to add to the partnership, which are worth exploring. Although Robyn is a knowledgeable and skilled early interventionist, she believes that she has much to learn from Michelle, as Isabella’s mother, throughout the partnership.

Finally, the third quality that supports Skilled Dialogue is responsiveness, which includes respectful and empathic reactions (Barrera & Kramer, 2012). Regardless of what she discovers, Robyn will be ready to respond to Michelle with empathy and without judgment. The ability to do so requires professionals to turn potential assumptions into hypotheses (Barrera et al., 2003). For instance, Robyn may assume that she is unwelcome in Michelle’s home or that Michelle is not interested in being involved in EI because she missed an EI session, and because when Robyn was present, Michelle seemed distracted. However, Robyn could reframe her initial assumptions by asking herself, “I wonder why Michelle seems to ‘shut down’ during our sessions?” or “I wonder if Michelle might be overwhelmed by Isabella’s needs and even the EI system?” Robyn must be attuned to Michelle’s circumstance and respond sensitively. When responding to caregivers, professionals who use the Skilled Dialogue framework should be open to the unexpected as they explore and discover a family’s true reality, thoughts, behaviors, or perspectives.

Six Strategies for Open Dialogue

The six strategies, which can be utilized to convey respect, reciprocity and responsiveness are: welcoming, allowing, sense-making, appreciating, joining, and harmonizing (Barrera & Kramer, 2012). Each strategy is discussed and explained within the context of the vignette.

Welcoming and Allowing

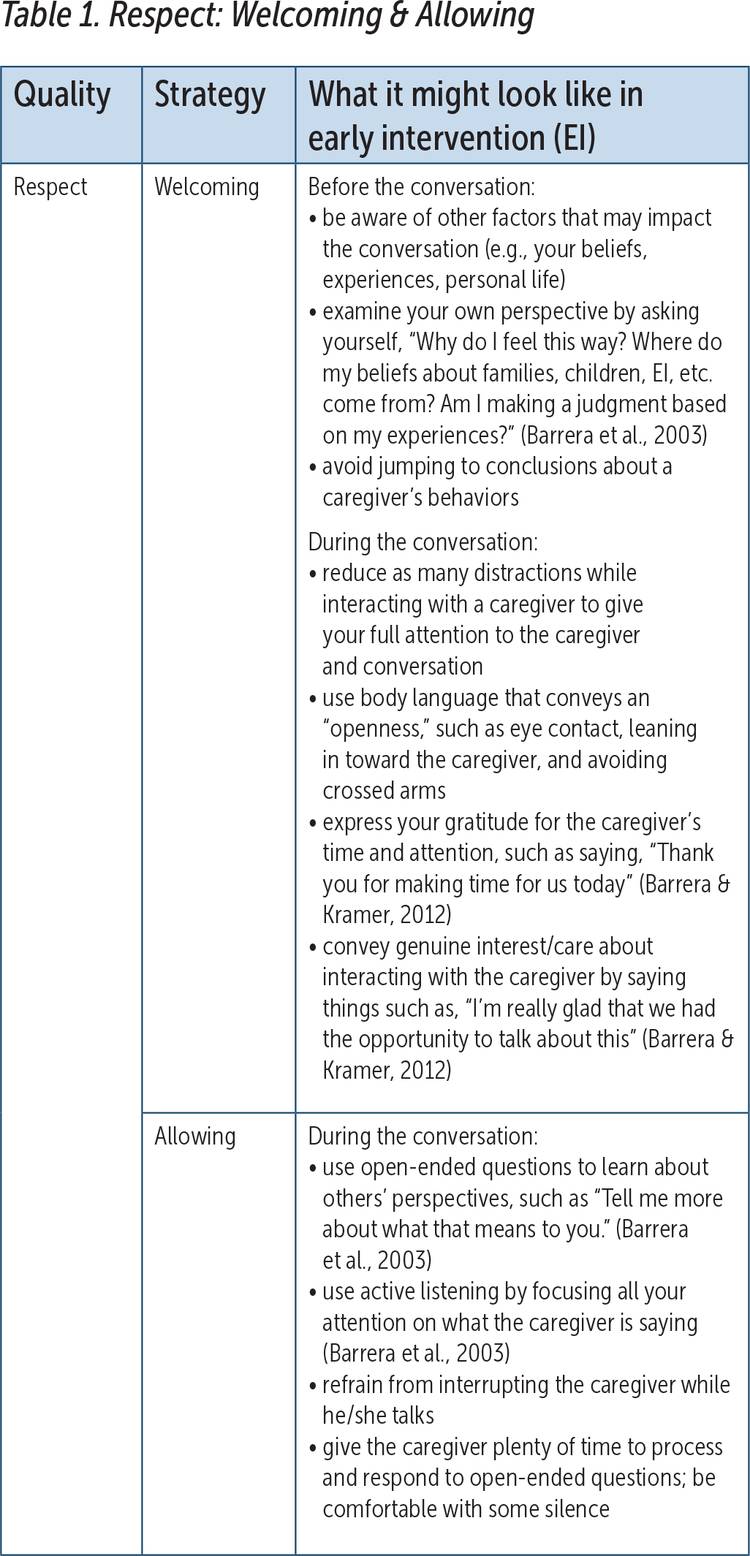

Respect may be illustrated through the strategies of welcoming and allowing. Welcoming involves the words and behaviors that professionals use with caregivers to recognize their value and the opportunity to interact with them. This strategy is intended to communicate to caregivers that professionals look forward to interacting with them. A complimentary strategy to welcoming is allowing. This strategy supports the existence of different perspectives and encourages these perspectives to co-exist. Both welcoming and allowing are intended to create the time and space for caregivers to express their viewpoint before professionals express their own (see Table 1 for examples). By actively listening to caregivers’ viewpoints and opinions, EI professionals demonstrate their openness and the possibility of collaborating to develop outcomes that are amenable to both parties. Welcoming and allowing are aimed at building and sustaining respect throughout interactions with a caregiver (Barrera & Kramer, 2012).

Robyn uses welcoming and allowing, as suggested by the Skilled Dialogue Framework, to embrace the opportunity to interact with Michelle. Although it may feel unnatural at first, she strives to understand Michelle’s perspective and to promote a partnership with her. As Robyn uses welcoming, she is mindful of her nonverbal behaviors as she ensures her full attention is on Michelle and the conversation at hand, eliminating other distractions, such as her cell phone or EI session notes.

During the next home visit, Robyn says, “Michelle, I’m so glad that we were able to find a time to meet today that was convenient for both of us. As I mentioned over the phone, I really value all that you know about Isabella and I want to learn more about your daughter from you. So, thanks again for meeting with me today.”

True reciprocity means believing that everyone has something to share and contribute. Photo: Jaren Jai Wicklund/shutterstock

After she uses the welcoming strategy to communicate to Michelle that she values the opportunity to talk with her, Robyn uses allowing to “make space” for Michelle’s perspective. Instead of jumping to conclusions about Michelle’s nonverbal and verbal behaviors (and what they might mean), Robyn strives to understand Michelle’s perspective. Robyn begins by describing what she has observed without judgment, and then provides Michelle with an opportunity to share her experiences and perspective.

Robyn continues by saying, “I know during our initial evaluation and Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) development meeting, you mentioned wanting to do everything possible to help Isabella develop, which is critical as you are her first and most important teacher. Early Intervention ascribes to a family-centered philosophy, which means that we value all caregivers and recognize the impact they have on their children’s development. Together, we can identify practical strategies that you can implement throughout your daily routines and interactions with Isabella, to promote her development and participation in family life, which you mentioned are priorities for you. With that in mind, I’ve noticed you’re not always available for our sessions. Additionally, I have noticed that you sometimes do other things while I am here, such as talk on the phone or do household chores. So, I wanted to take this opportunity to learn more about what might be going on for you in terms of making our sessions work and your being able to participate meaningfully in EI.”

After Michelle listens to Robyn, she responds by saying, “well…I’m really sorry that I did not text you and cancel our sessions before you showed up at my house. As you know, I’m a single mom and my boss is asking me to work more and more, so that’s why I haven’t been at home the last two weeks for our morning visits. Also, I don’t know anyone who has Down syndrome, so all of this with Isabella is so new and at times frightening to me. Sometimes I feel overwhelmed by her diagnosis and keeping up with all her appointments. I can’t always handle it and don’t feel supported by my own family. And honestly, talking about it makes me feel even more overwhelmed.”

Sense-Making and Appreciating

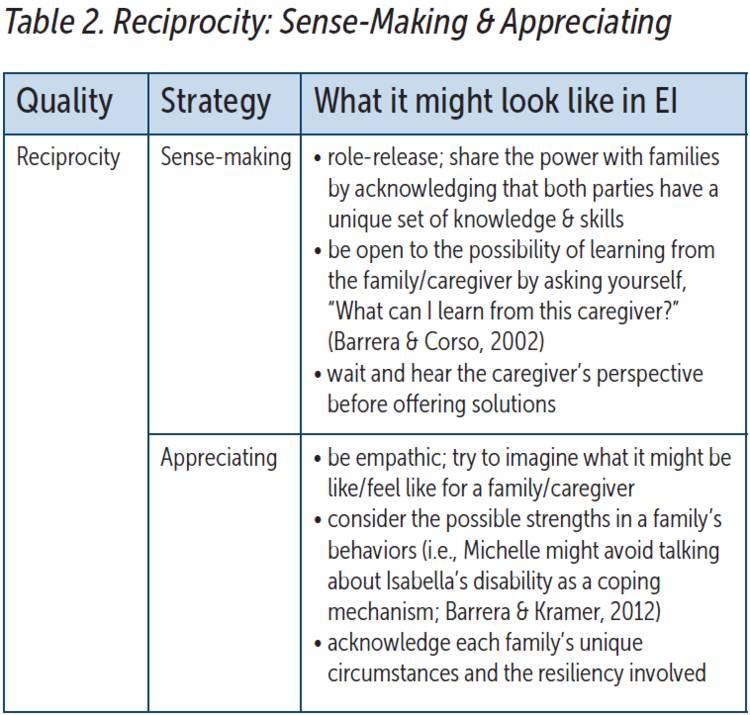

Reciprocity, the second quality that supports Skilled Dialogue, may be expressed through the strategies of sense-making and appreciating (see Table 2 for examples). The objective of sense-making is to truly understand a caregiver’s unique perspective and experiences. This strategy requires professionals to be empathic and adept at perspective-taking (Barrera & Kramer, 2012). Sense-making means that Robyn must truly attempt to understand, as best as she can, Michelle’s set of unique circumstances, even if they are different from her own experiences. For example, Robyn chose for her profession to be in the field of EI, whereas Michelle did not. Robyn might try to imagine how Michelle must feel with Isabella’s new diagnosis and entry into the EI system, in addition to her other life circumstances and how all those variables could affect her.

In response to Michelle’s comments, Robyn responded by stating, “Let me make sure that I understand you correctly. Are you saying that you’re overwhelmed right now with all of Isabella’s needs? And, realizing that she has a disability is difficult for you?” Michelle nodded her head “yes.” Robyn then asked, “In addition, you’re trying to balance the needs of your family and job all at once?” to which Michelle replied, “That’s right.” Finally, Robyn said, “This helps me better understand your circumstances. Just one more question, do you have help with child care? In other words, who watches Isabella while you’re working?” to which Michelle stated, “My mom helps me and watches Isabella most often.”

Through these questions and comments, Robyn begins to better understand Michelle’s perspective and experiences.

Meanwhile, when using the strategy of appreciating (see Table 2 for examples), professionals can actively acknowledge the strengths in one’s behaviors while realizing the limitations (Barrera & Kramer, 2012). For instance, Robyn may realize the positive aspects associated with Michelle’s behaviors—Michelle has been canceling sessions so that she can make it to work and provide for her family. And, Michelle may have been avoiding interactions with Robyn as a way of coping with feeling overwhelmed, uncertain, and fearful. Although Robyn is able to see the strengths in Michelle’s behaviors, she also recognizes that Michelle is missing out on opportunities to meaningfully participate in the EI process and Isabella’s development.

Robyn adds, “I appreciate you sharing that with me, and I realize that it may not have been easy for you to open up like this.”

Joining and Harmonizing

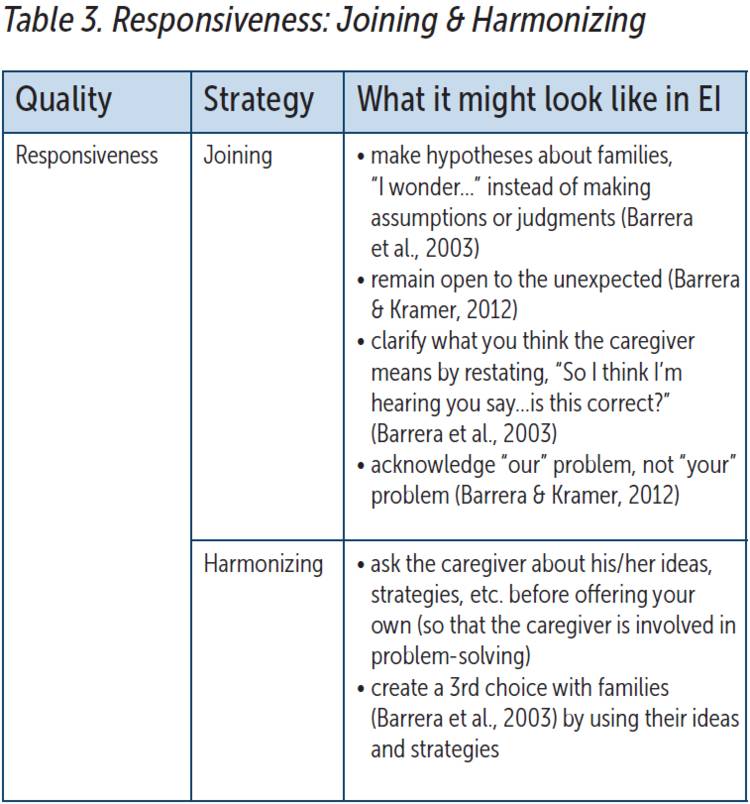

Once Robyn is better able to make sense and appreciate Michelle’s circumstances and her behaviors, she can consider how Michelle might be able to contribute to the solution. The third quality within the Skilled Dialogue framework is responsiveness, which is illustrated through the strategies of joining and harmonizing (see Table 3 for examples). Joining within the context of EI means bringing together two different, but equally important, voices. According to Barrera and Kramer (2012), joining acknowledges similarities and differences as “it joins without erasing” (p. 21). Furthermore, joining suggests that professionals assume accountability in the partnership by collaborating with families to become part of the solution (Barrera & Kramer, 2012).

When Robyn states, “I would love to put our heads together and come up with some possible strategies or supports around working and balancing your family’s needs, and coping with the feeling of being overwhelmed that you mentioned. How does that sound?” Michelle responds, “Yeah, we can do that.”

Harmonizing is an extension of joining because it is a strategy used to bring together both caregivers’ and professionals’ perspectives and ideas as solutions are considered. The potential strategies, ideas, or solutions do not need to belong exclusively to a caregiver or professional. In fact, it is possible to have a third choice, which may capture both parties’ perspectives and ideas (Barrera et al., 2003). In the previous example, Robyn used joining to set the stage for harmonizing with Michelle.

Robyn continued the conversation by saying, “Well, it seems like we’re talking about two things here: your job, which is making it difficult for you to participate in our weekly sessions, and your concerns about Isabella. So, what might make it easier for you to be present and fully participate during our sessions?” Michelle responded, “Since I’m going into work earlier than usual, maybe we could meet even earlier, like 7:00 or 8:00 a.m. instead of 11:00 a.m.?” To which Robyn replied, “That’s a great idea, Michelle. Let’s look at our calendars and see when that might work. Also, because your mother spends a lot of time with Isabella, and has the potential to promote her communication skills, I’m wondering if she might be open to participating in EI services sometimes? Perhaps every other week or once a month, I could meet with her and then with you the rest of the time? That way, your mother is involved, if she is open to that, and you’re involved as well. What are your thoughts about this?” Michelle considered Robyn’s idea and replied, “That sounds good to me. Let me ask my mom if that would work for her and then get back to you. In the meantime, though, we can schedule an early morning session for next week.” Robyn delightfully responded, “Great, it sounds like we have a few options here. And, we can always change this arrangement as your schedule changes and new priorities for Isabella emerge. In terms of feeling overwhelmed, who do you have in your life to talk with or receive support from?” Michelle thought for a moment and hesitantly said, “Well I’m not really sure. I guess my mom, but she does not always understand me and what I’m going through.” Robyn empathically responded to Michelle by saying, “Well, I’m wondering if it might be helpful to talk with another mother who has been through the early intervention process and knows what it is like to raise a child with Down syndrome. That way you can ask her about her experiences, feelings, resources, etc.” Michelle took a deep breath and replied by saying, “Yes, it might be really helpful to talk with someone who is in a similar circumstance.”

Instead of focusing on one person’s ideas, Robyn used harmonizing and thus both perspectives were considered and a plan was jointly developed based on the ideas proposed and agreed upon by Michelle and Robyn. Instead of Robyn telling Michelle what to do and how to solve her problems, they discovered new, creative ideas together and agreed upon what was most appropriate and feasible for the family at that moment in time.

Conclusion

According to Turnbull, Turnbull, Erwin, Soodak and Shogren (2015), one of seven principles of family–professional partnerships is equality and ideally entails “power-shared” interactions with families instead of “power-over” interactions. Skilled Dialogue is a framework that promotes open communication and partnership among two parties who have different positions, perspectives, beliefs, and/or opinions. Through the promotion of respect, reciprocity, and responsiveness in EI, professionals have the potential to truly share power with caregivers, building on their unique strengths and capacities to participate in the process and meet their own needs. Although Skilled Dialogue may not be appropriate in every situation, it is a practical framework when implementing DEC’s recommended practices with families in EI, thereby strengthening family professional partnerships.

When responding to caregivers, professionals who use the Skilled Dialogue framework should be open to the unexpected as they explore and discover a family’s true reality, thoughts, behaviors, or perspectives. Photo: Monkey Business Images/shutterstock

Initially, Robyn assumed that Michelle was not interested in partnering with her and being involved in EI. If Robyn continued to believe this, she may have excluded Michelle from the partnership, significantly impacting Michelle’s and Isabella’s EI experiences and outcomes. However, Robyn followed the Skilled Dialogue framework thereby avoiding assumptions, making sense, empathically responding, and discovering with Michelle. As a result, Robyn strengthened her relationship with Michelle and actively engaged her in the problem-solving process. These strategies have the potential to empower Michelle as an equal partner in the process and situate Michelle as Isabella’s advocate, an important role Michelle will play as she navigates other programs and experiences in Isabella’s future.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to express profound thanks to the Early Intervention Training Program at the University of Illinois, funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Human Services Bureau of Early Intervention (FCSWO04014). This article was also supported in part by funding from the Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education: Project IMPACT (H325D150036). The views or opinions presented in this manuscript are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the funding agency.

Authors

Kristen Schraml-Block is a doctoral student in the Department of Special Education at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Her work in early intervention involves the implementation of family-centered, capacity-building practices with families caring for infants and toddlers with developmental delays and disabilities as well as developing and facilitating learning opportunities for professionals. Her current research interests include exploring families’ experiences in early intervention.

Michaelene M. Ostrosky is a professor in the Department of Special Education at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Throughout her career, she has been involved in research and dissemination on inclusion and the acceptance of children with disabilities, social–emotional competence, social interaction interventions, and challenging behavior.

Suggested Citation

Schraml-Block, K., & Ostrosky, M. M. (2018). Respect, reciprocity, and responsiveness: Strengthening family-professional partnerships in early intervention. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(2), 5–10.

References

Barrera, I., & Corso, R. (2002). Cultural competency as skilled dialogue. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(2), 103–113.

Barrera, I., Corso, R., & Macpherson, D. (2003). Skilled dialogue: Strategies for responding to cultural diversity in early childhood. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Barrera, I., & Kramer, L. (2012). Using skilled dialogue to transform challenging interactions. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Bruder, M. B. (2000). Family-centered early intervention: Clarifying our values for the new millennium. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 20(2), 105–115.

Division for Early Childhood. (2014). DEC recommended practices in early intervention/early childhood special education 2014. www.dec-sped.org/dec-recommended-practices

Education of the Handicapped Act Amendments of 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-457, 100 STAT 1145 (1986).

Keilty, B. (2017). Seven essentials for family-professional partnerships in early intervention. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Lyon, S., & Lyon, G. (1980). Team functioning and staff development: A role release approach to providing integrated educational services for severely handicapped students. Research and Practice for Persons With Severe Disabilities, 5(3), 250–263.

McCollum, J. A., & Hughes, M. (1988). Staffing patterns and team models in infancy programs. Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Turnbull, A., Turnbull, R., Erwin, E., Soodak, L., & Shogren, K. (2011). Families, professionals, and exceptionality: Positive outcomes through partnership and trust. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.