Joy D. Osofsky, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, Louisiana

Jenifer Goldman Fraser and Amy Huffer, ZERO TO THREE, Washington, DC

Janie Huddleston and Darneshia Allen, ZERO TO THREE, Washington, DC

Alexandra Citrin and Juanita Gallion, Center for the Study of Social Policy, Washington, DC

Sufna G. John, University of Arkansas Medical Center, Little Rock

Abstract

Structural racism in the United States through federal and state legislation and public policies has systematically disadvantaged families of color leading to societal inequities and generations of families living in poverty. Further, racist ideas have led to the exclusion of families of color from systems of support that could prevent involvement with child welfare. The Safe Babies Court Team™ approach is an innovative program for child welfare-involved children and families supporting cross-systems integration and collaboration. Through this program, many inequities within the child welfare system can be recognized and addressed. The methods embedded in the core components of the SBCT approach set the stage for advancing racial equity. The article also includes reflections, through the lens of cultural humility, about what is needed to strengthen the capacity of SBCTs in addressing systemic racism and discriminatory practices in the child welfare system through equitable supports, services, procedures, and policies.

Policies and systems that are grounded in racist ideas have led, and continue to lead, to the exclusion of families of color from systems of support that could prevent involvement with child welfare. (Citrin et al., 2021, p. 4)

Structural racism in the United States, manifested in the long history of federal and state legislation and public policies that have systematically disadvantaged families of color, has led to deeply rooted societal inequities and injustice resulting in generations of families living in poverty (Aspen Institute, 2005; Hayes-Greene & Love, 2018). This institutionalized racism has shaped and perpetuates social and environmental conditions that undermine access to safe and stable housing, good-paying and stable jobs, healthy food, health care, and other services and supports that promote well-being—conditions that are disproportionately experienced by children and families of color as starkly illuminated by the COVID-19 pandemic (Children’s Defense Fund, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2019; Evans, 2020).

A brief from the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University (2021), based on a publication in the Annual Review of Public Health (Shonkoff et al., 2021), emphasized the clear and growing scientific evidence that both structural racism and interpersonal bias and discrimination impose substantial stressors on the daily lives of families of color with young children. Approximately 3 in 4 children living in poverty (71%) are children of color (Children’s Defense Fund, 2021). Among families with very young children who are low income or living in poverty, the highest percentage are American Indian/ Alaska Native (63%), African American (61%), and Latino (54%) compared with White (29%) families (Keating et al., 2021). For both American Indian/Alaska Native and African American families living in poverty, these percentages are at or nearly double the national average of 18.6% (Keating et al., 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, poverty among all age children increased by nearly 2 percentage points, but the increase was particularly acute for Latino and African American children in female-headed households (Chen & Thomson, 2021), demonstrating how current policies and systems create additional barriers for these families in accessing supports in times of need.

Racial Inequity and Disparities in the Child Welfare System

For parents living with the daily stressors of poverty, providing care and supervision for very young children can be extremely difficult (Sweetland, 2021). In combination with the trauma of racism in daily life and the generational experience of historical violence and institutional oppression in this country, the burden on families of color can exert itself as chronic wear-and-tear or “weathering” (Forde et al., 2019; Geronimus et al., 2006; Williams & Wyatt, 2015). This weathering, in turn, can lead to chronic and serious physical health problems and mental health struggles, including substance use disorders and complex trauma, that impact caregiving (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2021; Wilkinson et al., 2021). For many families of color in the United States, the compounding impact of policy decisions and systemic racism are drivers of disproportionate involvement with child protective services and over-representation of children of color, particularly African American children, in foster care (Bailey et al, 2017; Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016; Derezotes et al., 2005; Minoff, 2018; Summers, 2015; Wells, 2011). According to the most recent data available for Federal Fiscal Year 2019 (Children’s Bureau, 2021), 20.9% of children in the child welfare system with substantiated or indicated maltreatment were African American, yet African American children make up only 13.7% of the general population.

In addition, numerous studies have shown that racial bias and racial inequities occur at various decision points in the child welfare continuum (Association for Maternal and Child Health Programs Innovation Hub, n.d.). Although race and ethnicity do not strongly correlate with rates at which maltreatment is substantiated, systemic racism drives reports of maltreatment of African American children being investigated at higher rates than those for White children, contributing to their over-representation in the child welfare system (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). African American families are also less likely to receive needed services, and their children are more likely to be removed from their homes (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016; Ganasarajah et al., 2017; Martin & Connelly, 2015). Research also shows that once in care, there is less support for family reunification as children of color receive fewer familial visits, fewer contacts with caseworkers, fewer written case plans, and fewer developmental or psychological assessments (Bass et al., 2004). These children also tend to remain in foster care placement longer (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016). Structural racism and implicit bias compound and contribute to these many disparate outcomes. Further, systemic barriers and challenges that are the results of longstanding structural racism can prevent families from accessing services due to where they live, unreliable transportation or limited resources to access transportation, and experiences of discrimination that have cultivated distrust of service providers and the child welfare system.

In this article, we describe how the Safe Babies Court Team™ approach, an innovation that cultivates cross-systems integration and collaboration for child welfare-involved young children and families, creates the context in which the myriad inequities embedded in and perpetuated by the child welfare system can be recognized and addressed. Specifically, we discuss several pathways via which core components of the SBCT approach can set the stage for advancing racial equity. We close with reflections, through the lens of cultural humility, about the road ahead for strengthening the capacity of SBCTs in addressing systemic racism and discriminatory practices in the child welfare system at large through equitable supports, services, procedures, and policies.

The SBCT Approach

In 2005, the seeds of the SBCT approach emerged as an innovation to address the significant systems gaps and challenges in meeting the urgent developmental needs of infants and toddlers in foster care (Osofsky et al., 2007, 2017). This groundbreaking work prioritized a therapeutic approach in supporting very young children and their parents through timely developmental screening and supports, evidence-based intervention to heal the parent–child relationship and promote healthy attachment relationships, and cross-system collaboration focused on building a more coordinated and integrated system of care.

Across the two decades following this early work, ZERO TO THREE has served as a national resource center providing training and technical assistance (T&TA) to communities and states seeking to implement SBCTs—which are recognized as a promising evidence-based approach for applying the science of child development in the child welfare system (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2016). Between 2014 and 2018, ZERO TO THREE operated the national Quality Improvement Center for Research-Based Infant–Toddler Court Teams (Quality Improvement Center) with funding from the Administration for Children and Families’ Children’s Bureau (in partnership with the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP), the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, and an independent evaluation team at RTI International). Findings from the Quality Improvement Center’s multisite evaluation study showed a host of positive outcomes for SBCT children and families including timely access to needed services and permanency, with race-equity analyses demonstrating no differences in outcomes for children and families of color compared with White children (Casanueva et al., 2017, 2019).

Since fall 2018, ZERO TO THREE has served as the national Infant-Toddler Court Program with funding from the Health Resources and Services Administration Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The program is a partnership with the American Bar Association Center on Children and the Law, CSSP, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, and an independent evaluation team at RTI International.

In this capacity, ZERO TO THREE continues to provide SBCT implementation support to communities across the country with the preventative goal of promoting the health and well-being of children and families involved with the child welfare system. Across its long history of supporting uptake of the SBCT approach, ZERO TO THREE’s work and presence in the field has evolved in important ways. First, SBCTs are increasingly working with families whose very young children are under court jurisdiction but remain in the home to prevent removal. Second, guided by the vision that all young children and families should be supported by a full continuum of prevention supports, SBCTs are even more explicitly taking a two-generation approach in meeting the needs of the whole family. Third, SBCTs are pushing upstream attention to the social and environmental conditions that drive health and well-being and prevent abuse and neglect in the first place by advocating for greater availability and access to prevention supports (ZERO TO THREE, n.d.-a). To capture this expanded prevention work, the program recently updated the logic model for the SBCT approach. This updated logic model incorporates a framework for the approach, represented in five strategic practice areas:

1. interdisciplinary, collaborative, and proactive teamwork;

2. enhanced oversight and collaborative problem-solving;

3. expedited, appropriate, and effective services;

4. trauma-responsive support; and

5. continuous quality improvement.

Embedded in this strategic framework are the SBCT 10 core components, which work together synergistically to maximize child, parent, family, and community benefits (ZERO TO THREE, n.d.-b; see Table 1). Today there are 106 sites across 31 states receiving implementation support from the Infant-Toddler Court Program, which includes scale-up work with eight state-level teams.

Table 1: Core Components and Key Activities

Integral to the program’s emphasis on prevention and well-being is the vision and commitment to address racial inequities and disparities in the child welfare system (Child Welfare Information Gateway, 2016; Quality Improvement Center for Research-Based Infant-Toddler Court Teams, 2016; Wilkinson et al., 2021). A key strategy in moving this vision forward has been partnering with experts in historical trauma, diversity, and cultural responsiveness including:

- Dr. Marva Lewis of Tulane University, whose expertise on the legacies of the historical trauma of slavery, methods for resilience-building in African American communities, and facilitating courageous conversations in child welfare to address racial equity deeply informs the work of the program (Lewis, 2012; Lewis et al., 2011; Lewis & Ghosh Ippen, 2004). Dr. Lewis’ many contributions in building

the capacity of SBCTs to address equity include specific practices and strategies for supporting the young child’s family culture when placed in out-of-home care, building trusting partnerships in SBCTs for convening conversations about race, and engaging in the reflective and collective work needed to recognize and combat implicit bias. - Dr. Eduardo Duran, a clinical psychologist with expertise in healing approaches with Native American families and the legacy of Native Peoples’ experience of historical trauma, was essential for the program’s work with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians under the Quality Improvement Center (Duran et al., 2005). Dr. Duran provided crucial knowledge of working with Tribal communities and culturally specific strategies for supporting families participating in the SBCT approach. These strategies included incorporating families’ traditional healing rituals in child–parent psychotherapy and weaving ways to protect families’ cultural identity into their child welfare journey.

- Experts in child welfare policy and practice at CSSP (e.g., Citrin et al., 2021), in collaboration with Dr. Lewis, led the development of a foundational set of tools and strategies for building the knowledge, intention, and skills essential for advancing race equity in SBCTs. These include a tool to assess racial bias and a Race Equity Assessment Tool that provides a specific structure and guidance for sites (the latter resource is described later in this article). CSSP’s longstanding intensive focus on racial equity and justice, and expertise on child welfare inequities and helping states and communities confront those inequities, has been essential in laying the groundwork for SBCT sites to engage successfully in this work.

Together, the contributions of these experts laid the bedrock for how SBCTs—with intention and commitment—can be a pivotal force in advancing equity for young children and their families in the child welfare system, as described in the section that follows.

How the SBCT Approach Can Drive Equity

The SBCT approach is in a unique position to set the stage for (a) addressing racial inequities and disparities in the child welfare and dependency court process and (b) advocating for the social and environmental conditions that promote and support healthy families. Race equity work can be channeled through several core components of the approach, at the heart of which is respect and valuing of families:

1. the systems-level improvements pursued by the SBCT Active Community Team,

2. the collaborative problem-solving and support provided to families by the SBCT Family Team, and

3. the anchoring role of the SBCT community coordinator in carrying out the work of both teams and ensuring vigilance for race equity in every corner of a local SBCT site.

The Safe Babies Court Team approach is in a unique position to set the stage for addressing racial inequities and disparities in the child welfare and dependency court process and advocating for the social and environmental conditions that promote and support healthy families. Photo: Amanda Penley, Safe Babies Court Team Community Coordinator, Duluth, Minnesota

The Active Community Team

- This multisector stakeholder group, which the community coordinator is instrumental in convening and supporting, comprises leaders and providers from state agencies, community groups, and nonprofit organizations that come together with a shared vision of improving outcomes for infants and toddlers and their families. This group provides the space for community and system partners to bring and engage in trainings to understand the impact of structural racism or implicit bias (described further in the next section). With the increased knowledge and skills, this group can strategize on reducing disparities, building more equitable services and supports, and addressing racist policies and discriminatory practices. Equally important, the Active Community Team also can play a leadership role in the community by advocating for comprehensive and equitable community services that promote protective factors and prevent child abuse and neglect. There are several specific ways that these community-level teams can advance racial equity with intentionality, commitment, and the capacity to do so, including the following:

- Diversity on the Active Community Team is highly valued. Professionals, parent mentors, parent advocacy groups, and other community representatives who reflect the make-up of the community in which they serve are sought out for their participation in this stakeholder group. This diversity allows for solutions and systems improvements that meaningfully address needs as perceived by families and their communities.

- The Active Community Team works to foster an environment of learning by facilitating trainings that enhance the community’s capacity to meet the full range of needs of very young children and their families. These trainings can include the opportunity for professionals to come together, across disciplines, to increase awareness and understanding of the impact of structural racism and implicit bias on families of color in the child welfare system. Raising awareness, particularly self-awareness, about the root causes of inequities and the impact of implicit bias is key to eliminating the policies, practices, attitudes, and cultural messages that reinforce differential outcomes by race or fail to eliminate them (Aspen Institute, 2005). It is important to note that trainings also establish a common language among the team, which is essential to engaging in collective work in advancing race equity.

- The Active Community Team can serve as platform for opening conversations about personal biases, community discrimination, and institutional barriers—and commits to addressing these barriers. Stakeholders can identify gaps in services that are culturally responsive and equitable and advocate for building capacity to address these gaps.

- The Active Community Team provides the space for professionals to commit to and engage in the intentional and often uncomfortable work of recognizing and dismantling the discriminatory practices and policies embedded in the multiple systems serving children and families. This work is accomplished through vigilance in monitoring data disaggregated by race and ethnicity to identify systems gaps and needed improvements and carrying out targeted initiatives and intentional systems reform. This case-level data, which includes child and family needs, referrals, and services received as well as child welfare case outcomes, is entered into the national SBCT Database (maintained by the Infant-Toddler Court Program at ZERO TO THREE) by the SBCT’s community coordinator. The Active Community Team also compares the data among families served by the SBCT with state data, offering further opportunities for reflection about the disparities that are present in the child welfare system that need to be addressed. As disparities are identified, the Active Community Team can engage in collective problem-solving to respond to gaps in service availability, accessibility, and alignment. These efforts may include proposing new policies or procedures at the local, county, and state levels that reinforce and sustain best practices across systems to prevent children from entering care and responding more effectively to the needs of children and families who are in care.

The Family Team

This multidisciplinary team includes the parent, family members, SBCT community coordinator, child service workers, court-appointed special advocates, attorneys, resource caregivers, and service providers including adult and child mental health therapists and substance use disorder specialists. The SBCT family team meeting (FTM) is a specialized form of family group conferencing, in which the focus is on identifying and meeting the developmental needs of infants and toddlers and the comprehensive needs of the family. FTMs take place regularly and frequently throughout the life of the case to ensure that timely and effective prevention supports and intervention services address issues in as timely a way as possible. The team engages in proactive collaborative problem-solving as they work to

- prevent children’s removal and placement in foster care;

- promote reunification and other lasting permanency

outcomes; - strengthen family protective factors including enduring, positive social connections; and

- protect and build safe, stable, and nurturing early relationships.

This collaborative work drives meaningful assessment of case progress and the development of case goals including the delegated responsibilities associated with each goal. In this way, the FTMs create environments in which professionals and parents can share their perspectives and jointly problem-solve arising issues. (See Box 1.)

Box 1. Reflections on Safe Babies Court Teams

Professionals who are implementing the Safe Babies Court TeamTM approach share their reflections about addressing racial equity in their work:

The nice thing about the Safe Babies approach is a lot of the problems that you have with biases get removed because you’re focusing on the science and you’re focusing on solving the problem. The approach takes everybody above the bias issue because it’s scientifically based...so we use the science to help dictate the plan which changes a lot of the dynamic in the courtroom from a blaming mentality—whose fault is this—to a problem-solving mentality.

—Jami Hagemeier, Esq., parent attorney, SBCT Polk County, Iowa

Your life experiences shape how you navigate life, the decisions you make, and sometimes the mistakes you make, too. When you add the complexities of historical mistrust of government, and mistrust of court systems due to events which have had a catastrophic impact on the family nucleus, you can understand a family’s likelihood they will not engage as freely.

For these families, we work, we must work twice as hard to reach them where they are and engage them in the process...[and] we have to maintain a heightened awareness of our own personal biases when we have clients who struggle with historical trauma, or who may have been victims of institutional oppression.

—Carlyn Hicks, Esq., director, Mission First Legal Aid Office, Jackson, Mississippi

I think importantly for all of us, our clients are our biggest teachers [in terms of] sharing their experiences within their family and their culture. So we learn to ask some of those questions that maybe haven’t been typical for us: “What does this mean in your family? What does parenting look like in your family? What has marriage or relationships looked like in your family?” And just being able to ask those questions so that we can learn about what their perception is.

—Gwen Doland, MS, LMHC, CADC, substance use disorder clinical manager, Infant–Toddler Court Program and former child mental health clinician serving clients in the Des Moines, Iowa, SBCT

When an African American family comes in, one of my first thoughts is: “Is this family getting treated the same as if it was a White family?” And I look at where the case currently stands and see if things could have gone differently. Especially with families where there are substance use disorders and mental health issues, I recognize where the family is coming from and that what they are going through often has to do with historical trauma. With SBCT, I’ve learned to be more compassionate and understanding...how to really listen and provide support.

—Cindy Hernandez, MPH, community coordinator, Newborn to Three Court Team, New Haven County, CT

There are numerous strategies via which the Family Team can explicitly and implicitly advance equity for the families with very young children they serve, including:

- The team places the highest priority on developing trust with parents and empowering them through an inclusive participatory planning and decision-making process in which parents are consistently made to feel that their input is valued. Many families of color have experienced generations of historical violence and institutional oppression, so the work of building trust is essential (Lewis et al., 2011; Sotero, 2006). Through consistently respectful, affirming, transparent interactions on the part of each professional on the team with the family, slowly and steadily trusting relationships between the family and professionals develop. This trust then opens the door to unrestricted communication about the family’s needs and challenges and supports a trauma-responsive passage for the family as they navigate the child welfare and dependency

court processes. - Reflective practice is essential to a well-functioning SBCT Family Team. Self-awareness, which is fostered through reflective practice and diversity-informed practice, is a critical conduit for recognizing and managing bias which leads to better support for families (Ghosh Ippen et al., 2012). This reflective practice manifests itself in open and truthful dialogue during FTMs, which ideally are led by a neutral facilitator. The professionals on the team also engage in conversations outside of FTMs, commonly in debriefing about a case, to reflect on their own areas of strength and weakness in the interest of enhancing their effectiveness in supporting family needs and promoting positive outcomes for both the child and family (see Box 2).

Box 2. Reflective Practice Questions

Reflective practice among Safe Babies Court TeamTM professionals contemplates questions such as:

• How would I respond if this person were a different age/gender/ race/ethnicity?

• What is the basis for my assumptions about this person? How can I challenge those?

• How can I be an ally when stereotypes come up in interactions?

• What can I do to educate myself to become more aware?

• Who can help hold me accountable in this work?

Source: Gallion & Citrin, 2021

- FTMs emphasize participation of all the child’s caregivers (e.g., parents, kinship caregivers, resource parents), allowing the team to elicit the perspectives and resources of the full caregiving network and cultural context of the child and family. This inclusive approach helps to elevate the voice of the parent in the problem-solving process, which can help teams actively empower families as opposed to the propensity to rescue African American families.

- By including caregiver and family perspectives on areas of need and strength, FTMs benefit from inclusive conversations and sharing of knowledge across diverse perspectives. In this way, decision making does not just depend on the usual approaches and bodies of knowledge (Ghosh Ippen et al., 2012).

- The professionals on the Family Team work to communicate ideas and concerns in ways that are helpful rather than harmful. One key strategy is communicating directly with parents, not using jargon or legalese, so they participate fully in the discussion and feel confident in sharing their ideas and concerns. Whenever possible, FTMs refer families to services in their primary language and use interpretation services when members of the family or caregivers speak a different language from one another.

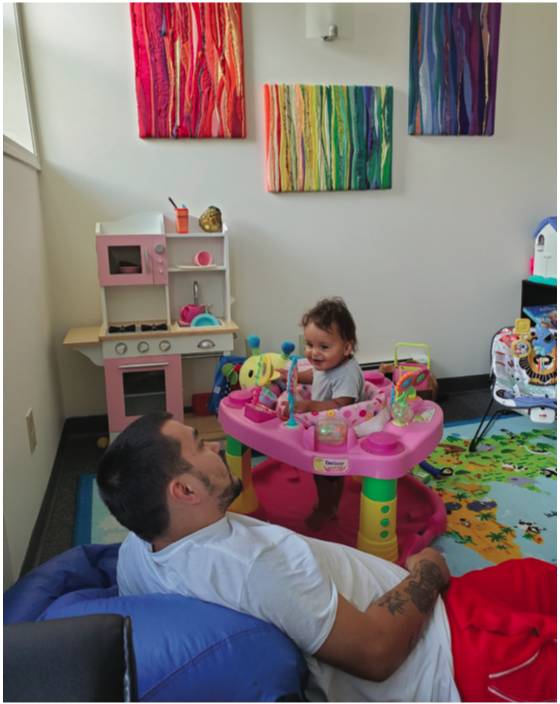

The Active Community Team can play a leadership role in the community by advocating for comprehensive and equitable community services that promote protective factors and prevent child abuse and neglect. Photo: Amanda Penley, Safe Babies Court Team Community Coordinator, Duluth, Minnesota

The Community Coordinator

In SBCTs, the role of the community coordinator brings the unique and invaluable presence of a neutral person to facilitate real-time communication across the cross-sector professionals on the Family Team, engage in outreach to build strong referral linkages, play a leading role in supporting the work of the Active Community Team, and be vigilant in calling attention to when bias may be influencing decision-making. In the traditional child welfare approach, adversarial relationships often exist among the professionals supporting the child and family as attorneys, case workers, and providers each advocate in the best interest of their client. The neutral position of the community coordinator acknowledges the adversarial relationships but, at the same time, helps the Family Team to hold in mind the infant’s need for safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and the parent’s needs—commonly related to their own histories of early childhood trauma—that may be affecting their capacity to provide such care. The community coordinator uses a reflective approach with the other professionals on the team, which can encourage insight into their own biases that may be affecting their perspective on the parent’s strengths and needs, and to build empathy toward the families being served. The community coordinator is positioned to create the reflective space for shared accountability and recognition of how bias influences practices in the Family Team and the Active Community Team. For example, the community coordinator may observe and point out when coded language, often heard in child protection, is being used (e.g., hostile, inner-city, noncompliant, sketchy neighborhood, ghetto, work ethic, illegal immigrant).

To gain insight into the parents’ experiences, the community coordinator empathically partners with parents throughout the process to gain an understanding of their needs and histories, some of which are laden with experiences of oppression, discrimination and racism, and historical trauma. The community coordinator helps the parents to be seen and heard in systems that have traditionally ignored them—and in which they often have felt oppressed and dismissed. An important part of this work is partnering with the child welfare caseworker to support a parallel process of empathy and equitable support for all parents. The community coordinator also plays an important role as a catalyst on the Family Team in encouraging reflections on issues of equity, bias, and culture. As an equity champion on the team, the community coordinator can help the Family Team recognize cultural considerations affecting the family’s participation in the case plan. This may include, for example, helping to identify partnering opportunities with resource caregivers to support parents in sharing information about their child, including foods and activities related to the family’s culture.

Family Time Advances More Equitable Outcomes

In addition to the many ways that the Active Community Team, Family Team, and community coordinator create the space for the collective work to advance race equity, the SBCT core component of frequent, high-quality family time is equally crucial for families of color whose children are disproportionately placed in out-of-home care. Children who have regular visits with their families are more likely to reunify (Chambers et al., 2016; Hudson, 2017; Leathers, 2002; Smariga, 2007). Family time is essential for maintaining and strengthening the parent’s healthy connection with their child (Harris Professional Development Network Child Welfare Committee, 2019).

In the SBCT approach, highly individualized plans for regular and meaningful family time are carefully developed to minimize anxiety, reduce stress, and prevent re-traumatization common to parents and children who are separated. With increased meaningful family time, the parent can continue to be actively involved in the child’s life and more readily begin addressing the issues that brought the child into care. Often, there are barriers that prevent more frequent contact, some of which disproportionately impact parents of color. However, community coordinators, in partnership with child welfare case workers and supervisors, can problem solve these areas of need, such as provision of transportation, supervision of the family time, and identifying home-like environments to conduct family time. Research conducted at multiple SBCT sites found that nearly 60% of SBCT cases have a high weekly frequency of contact, with 25.6% daily and 34.5% at least three times per week (Casanueva et al., 2019).

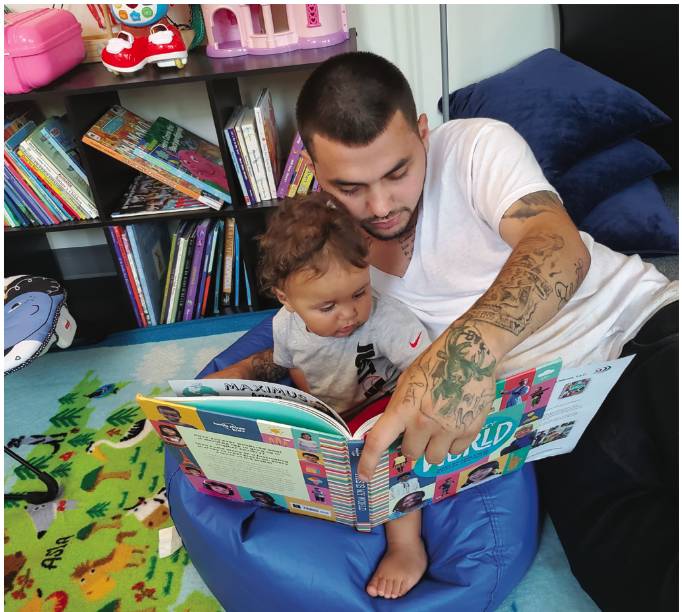

Family time offers an opportunity to affirm the diverse identities of children and families, ideally taking place in home-like settings where families can engage in culturally significant activities that celebrate both differences and similarities among people. Photo: Amanda Penley, Safe Babies Court Team Community Coordinator, Duluth, Minnesota

Best practices for family time offer an opportunity to affirm the diverse identities of children and families, ideally in home-like settings. Home-like settings are spaces that have comfortable places to sit, allow for quiet activities such as reading or putting a child to sleep, developmentally appropriate activities, and perhaps a place to cook and share meals or a snack. Home-like settings also provide opportunities for families to share culturally significant activities with their children. An example could be a family sharing a book with diverse characters and themes. Increasing access to books that are more inclusive of ethnic, cultural, and religious practices, people of color, people of different abilities, and people of diverse gender identities and sexual orientations who may identify as LGBTQ+ allows children to “celebrate both differences and similarities” as these types of stories serve as the mirrors to seeing themselves and the windows to seeing the outside world (Anderson, 2019). In addition to literature, parents should be encouraged to share their own family stories with children during family time. Family time can be a place where parents and the child’s current caregiver can work toward co-parenting and share culturally significant interests. Sharing books between the two households during family time (ZERO TO THREE, 2020) and sharing meals with foods from the child’s background can serve as a bridge to other conversations about the child’s family of origin. These best practice efforts for meaningful family time provide an opportunity to build trust and positive experiences between the team and the family, which can promote collaboration during the life of a case.

The SBCT Race Equity Assessment Tool and Strategic Planning

To further the capacity to support SBCTs in identifying and addressing systemic barriers to equity, members of the Infant-Toddler Court Program, in partnership with CSSP and Dr. Lewis, developed a Race Equity Assessment Tool to help sites take concrete steps in advancing equity (ZERO TO THREE, n.d.-a). This tool is designed to be used with the entire Active Community Team to facilitate intentional discussions about equity in the child welfare system and in the SBCT approach. The tool also promotes the Active Community Team’s capacity to serve as a community accountability mechanism to drive real change in reducing bias and increasing equity. It defines three steps, each with a set of “critical questions” to guide what can be difficult discussions and specific strategies for advancing equity:

1. Get the Big Picture by developing a shared awareness among stakeholders about racial disparities and disproportionality for children of color in the child welfare system, including review of national data and trends. This step involves training to increase knowledge and understanding about the issues confronting families of color including the history of racism, current structural racism, implicit racial biases and ways to mitigate biases at both the individual and systemic levels, and deep consideration of how disparate treatment of people of color affects their experience in the child welfare system and dependency court.

2. Focus on the Local: Lay the Foundation by affirming commitment to racial and social justice as integral to the vision for the local SBCT, ensuring diverse representation on the Active Community Team that reflects the racial and ethnic composition of the families being served, and collecting and reviewing data at the local level disaggregated by race and ethnicity to provide insight into the experience and needs of the children and families being served. This work involves considerable self-reflection among stakeholders and collective engagement.

3. Focus on the Local: Build the Structure by identifying priority areas, developing strategies to address disparities, engaging in continuous learning, and identifying opportunities to institutionalize and scale effective strategies. Both Steps 2 and 3 are continuous processes, ideally using a champion or champions to lead the work and ensure regular review of data and strategies to advance equity.

Since its development in 2017, the tool has been used as part of intensive T&TA with multiple sites to support strategic planning in advancing race equity. In the course of this work, the need for train-the-trainer workshops emerged to support sites in obtaining the skills for engaging families and professionals in discussion about race. One train-the-trainer that was developed focuses on supporting child welfare and other professionals in engaging and talking with families about their race, ethnicity, and culture as well as how to obtain accurate data about race and ethnicity from families. In one site, the training was conducted with the Active Community Team as well as case management staff in three counties and child protection investigators in one county. Another train-the-trainer workshop that was developed in response to a request from a site focused on the challenges in talking about race, where intense emotions associated with historical trauma and institutional oppression can lead to silence or avoidance when discussing topics of race, structural racism, racial disparities, equity, and social justice. This workshop particularly focused on implicit biases and unrecognized stereotyping that can influence communication among people from different racial, ethnic, or cultural groups. CSSP also developed an SBCT-specific data template to provide support in collecting and reviewing key data disaggregated by race and ethnicity to review and compare child welfare outcomes (e.g., time to reunification; time to reunification, adoption, or permanent guardianship; achieved permanency goals; return to care within 6 months; reasons for families not entering the SBCT).

With increased meaningful family time, the parent can continue to be actively involved in the child’s life and more readily begin addressing the issues that brought the child into care. Photo: Amanda Penley, Safe Babies Court Team Community Coordinator, Duluth, Minnesota

Currently, CSSP is engaged in intensive race equity T&TA for a sustained time with several SBCT sites. Following the steps outlined in the SBCT Race Equity Assessment Tool, this work is being carried out in tandem with the Infant-Toddler Court Program regional field specialists who work with these sites and through close collaboration with the community coordinators for the sites to plan the learning agenda and activities. To date, the T&TA has focused on addressing specific concerns and needs of the Active Community Team to build the foundation of a shared understanding of key equity terms and concepts, facilitate journey mapping, engage in a groundwater analysis (Hayes-Greene & Love, 2018), and identifying strategies and efforts being taken in other states (CSSP, 2015). CSSP introduced the Race Equity Impact Assessment (CSSP, n.d.) as an important tool to further the work. Based on the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Race Matters Racial Equity Impact Assessment (2009), adapted and tailored for child welfare policy decision-making, the tool provides questions to help assess whether a policy, practice, or decision disproportionately affects any group and asks questions about data, decision-making, outcomes, and perceptions. This intensive work has now led to the development of initial goals and strategies to advance equity, which the site will use as a roadmap for its specific agenda in advancing equity. With its strategic plan articulated, sites will continue to work with CSSP to prioritize and operationalize its next discrete steps in moving forward.

Reflections on Future Directions

While the content of this article was planned collectively by a diverse group of contributors, writing from an academic perspective about structural racism and interpersonal discrimination was an exercise in cultural humility for the White authors—giving rise to soul-searching and uncomfortable conversations about White privilege. This imperative for self-reflection was spurred by layers of racial equity trainings that our program staff have participated in at ZERO TO THREE. These trainings have raised awareness of the hard truths of individual bigotry and bias, increased understanding about the deep and sprawling roots of systemic racism in this country, and provided a foundation of commitment to naming and confronting racism (Center for Urban and Racial Equity, n.d.; Racial Equity Institute, n.d).

- As this article only briefly touched on the factors that contribute to disproportionality and disparities affecting families of color in the child welfare system are the result of hundreds of years of racism in this country’s federal and state policies and systems as well as individual bias. To address these disparities requires change in individual knowledge, attitudes, and practices, and changes in policy. The Infant–Toddler Court Program will continue its work on both these levels to dismantle systemic racism, discrimination, and bias for children and families of color. This work necessitates a strong commitment to cultural humility (Foronda et al., 2016), reflective practice, and vigilance in identifying areas of needed programmatic improvements. As the program moves forward with its work to advance equity, it will continue to seek training and consultation that enhances the program’s capacity to be a change leader in advancing equity in child welfare. Equally important, the program will draw on its National Advisory Group for Parents’ Voices—a diverse group of parents with lived experience launched in 2020—for direct input including guidance for culturally specific ways to promote resilience and the inherent strengths of families of color. This improvement work will particularly focus on building:

- equitable access to the full array of services and supports that meaningfully improve the lives of families of color,

- community capacity for intervention and prevention services that are culturally specific, and

- pathways that support diversity of parent engagement in Active Community Teams as well as state-level strategic planning for widespread implementation of SBCTs that is currently underway in multiple states.

At the policy level, important changes are needed to help to ensure equitable access to safe, stable, and nurturing environments that all children need to thrive (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, 2021). These changes are beginning to take shape through the Family First Prevention Services Act of 2018, which brought significant reforms to federal child welfare policy with its emphasis on building meaningful prevention supports and services for families and, more recently, the American Rescue Plan. With its historic increase in funding for the Community-Based Child Abuse Prevention program and investments in basic resources and policies that boost families’ economic security, the American Rescue Plan will reduce the burden on families—particularly families of color who were hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic—and make strides in addressing the critical needs of very young children and their families (ZERO TO THREE, 2021). With this transformative federal policy context as the background, the Infant-Toddler Court Program is releasing a new Policy Framework later this year that will put forth policy recommendations to advance the health and well-being of very young children who are at risk of entering or are in the child welfare system and their families. The framework asserts as a guiding principle the aim of removing barriers to racial equity and social justice, recognizing that advancing the health and well-being of very young children and their families requires an awareness of disparities that are pervasive throughout child and family systems, including health, early childhood education, and child welfare. Accordingly, equity is explicitly addressed throughout the recommendations in this new framework including policies and practices that directly address disproportionate rates of removal and placement in foster care for families of color, court processes that ensure families of color have adequate legal representation, and removing barriers to accessing needed services.

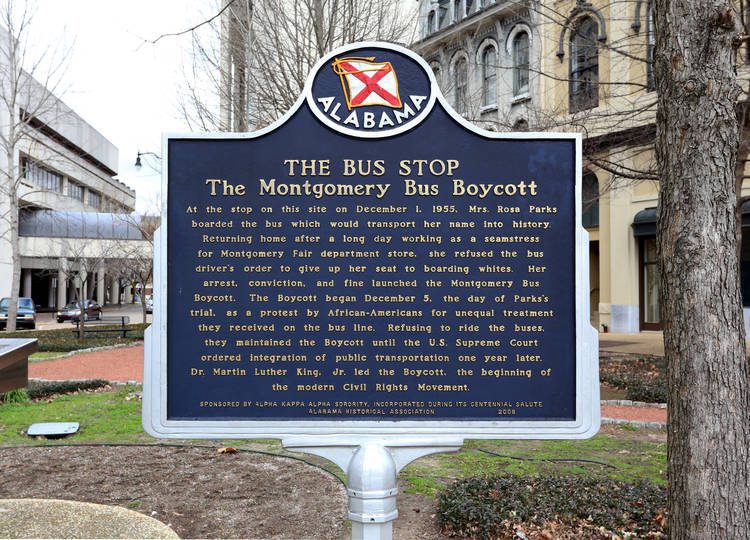

The factors that contribute to disproportionality and disparities affecting families of color in the child welfare system are the result of hundreds of years of racism in this country’s federal and state policies and systems as well as individual bias. Photo: Katherine Welles/shutterstock

Through its multifaceted and multilayered strategies to advance equity, the Infant-Toddler Court Program is setting its sights on reducing the overall number of babies and toddlers entering the child welfare system and, particularly, reducing the disproportionate number of children of color who enter care.

Ultimately, the goal is to transform the child welfare system into a system of child well-being and to support communities and states to address the social determinants of health so that every child and family, in every community, experiences the conditions that promote early childhood developmental health and empower families to flourish.

Acknowledgment

This program is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $9,948,026 with 0 percent financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

Author Bios

Joy D. Osofsky, PhD, is a clinical and developmental psychologist, Paul J. Ramsay Chair of Psychiatry and Barbara Lemann Professor of Child Welfare at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in New Orleans. Dr. Osofsky has published widely and authored or edited seven books on trauma in the lives of children. She is past president of ZERO to THREE and of the World Association for Infant Mental Health. Currently, she is on the board of ZERO TO THREE and serves as clinical consultant on the Leadership team for the ZERO TO THREE Infant Toddler Court Program/Safe Babies Court Team. She has had much experience with response to disasters, playing a leadership role in the Gulf Region following Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill as clinical director for Child and Adolescent Initiatives for Louisiana Spirit following Hurricane Katrina and co-principal investigator for the Mental and Behavioral Capacity Project following the Gulf Oil Spill. She currently serves as co-principal investigator for the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Center, Terrorism and Disaster Coalition for Child and Family Resilience.

Jenifer Goldman Fraser, PhD, MPH, is the director of research and evaluation for the national Infant-Toddler Court Program at ZERO TO THREE. Jenifer brings a comprehensive body of knowledge to strategic planning for evaluation, research, and implementation and dissemination methods that support effective uptake of the Safe Babies Court Team approach. A research developmental psychologist with public health training and experience, she specializes in infant and early childhood mental health, early childhood trauma, and implementation of evidence-based interventions. With 30 years of experience in both real-world and academic settings, her longstanding research and programmatic interests focus on addressing equitable access to services, supports, and resources so that all infants, toddlers, and their families thrive. Jenifer is an alumna ZERO TO THREE fellow (class of 2003–2005).

Amy Huffer, PhD, LCSW, IMH-E (IV-C), is a regional field specialist for the National Infant-Toddler Court Team at ZERO TO THREE. Dr. Huffer has specialized in infant and early childhood mental health, and currently supports efforts by ZERO TO THREE to change the trajectory for infants, toddlers, and their families impacted by the child protection system. She has supported the implementation of infant mental health principles across disciplines, while also supporting research efforts in the field. In addition, Dr. Huffer has been endorsed as an Infant Mental Health Mentor and regularly provides trainings and reflective consultation to professionals serving infants, toddlers, and their families.

Janie Huddleston, MSE, BSE, director of the national Infant– Toddler Court Program (ITCP) at ZERO TO THREE, brings more than 30 years of experience with education, child welfare, Medicaid, mental health, early learning, and system change to this position. She currently uses that experience and expertise to lead ITCP sites in the implementation of the Safe Babies Court Team™ approach in many sites across the US. This project is designed to support implementation and build knowledge of effective, collaborative court team interventions that transform child welfare systems for infants, toddlers, and families. Before this role she worked for the Arkansas Department of Human Services, in various positions including the director of the Division of Early Care and Education, director of the Division of Children and Family Services, director of the Division of Behavioral Health Services, and deputy director for the Department.

Darneshia Allen, is director of practice and field operations, National Infant-Toddler Court Program. Ms. Allen offers more than 33 years of experience working with young children. Her background includes intensive work with families in urban communities, years of experience in early care and education, which ultimately led to the development of a Pre-K 4 program. Ms. Allen first joined ZERO TO THREE as the Arkansas community coordinator for the Pulaski County Safe Babies Court TeamTM Project in 2009. In continuous leadership roles, Ms. Allen has provided support for other communities implementing the Safe Babies Court Team approach. She previously led the work as a statewide training and outreach coordinator and Quality Improvement Center for Infant Toddler Court Teams technical assistance specialist prior to becoming the senior technical assistance specialist in 2018. She now serves in the role of director of practice and field operations. Ms. Allen holds her bachelor of science in elementary education from the University of Central Arkansas.

Alexandra Citrin, MSW, MPP, senior associate at the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP), is an expert in child welfare policy and practice, including upstream prevention, and its effect on communities of color, LGBTQ+ youth, and immigrant families. Alexandra has been deeply involved in working with states and national partners to understand the complexities and requirements of the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA) and identifying opportunities within the bill to advance child welfare system reform efforts both as it relates to prevention services and the reduction of congregate care. She currently leads the team providing intensive technical assistance to states developing and implementing prevention activities through FFPSA. Alexandra’s system-reform work also includes providing technical assistance to state and local child welfare systems through child welfare systems operating under federal consent decree and the Infant Toddler Court Team Program. She is a trained reviewer for the Child and Family Service Review and Quality Service Review. Her policy expertise includes child welfare system and finance reform, health care, and immigration—with a focus on using frontline practice knowledge to inform equity-focused policymaking.

Juanita Gallion, AM, deputy director of Equity & Learning at the Center for the Study of Social Policy (CSSP), helps lead

the organization’s work to advance racial equity through facilitation, training, capacity building, leadership development, and coaching with a variety of national and local partners and philanthropic organizations. In addition, she supports the learning culture within the organization, and shapes the creation and dissemination of lessons learned across CSSP’s various bodies of work. She previously managed the technical assistance and training for several large-scale community initiatives, including the U.S. Department of Education’s Promise Neighborhoods program, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Making Connections initiative to ensure families and communities had the resources they needed to achieve success.

Sufna G. John, PhD, is a licensed psychologist and associate professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) in Little Rock, Arkansas. She specializes in infant and early childhood mental health and trauma and is nationally certified in several evidence-based trauma treatments for children and families. She is also a state Child-Parent Psychotherapy and DC:0–5 trainer. She co-directs the Arkansas Building Effective Services for Trauma program, which focuses on improving outcomes for traumatized children and their families in Arkansas through excellence in clinical care, training, advocacy, and evaluation. She also co-directs the UAMS Complex Trauma Assessment Program, a partnership with the Arkansas Department of Child and Family Services to provide comprehensive, trauma-informed evaluations for high-risk youth in the child welfare system. She also serves in a consultant role for ZERO TO THREE, providing support for Safe Babies Court Teams across the state of Arkansas.

Suggested Citation

Osofsky, J. D., Fraser, J. G.,Huffer, A., with Huddleston, J., Allen, D., Citrin, A., Gallion, J., & John, S. G. (2021). The Safe Babies Court Team approach: Creating the context for addressing racial inequites in child welfare. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(1), 48–60.

References

Anderson, J. (2019). Hooked on classics 2019. Harvard Graduate School of Education. www.gse.harvard.edu/news/ed/19/08/hooked-classics

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2009). Racial equity impact assessment. https://assets.aecf.org/m/resourcedoc/RF-RacialEquityImpactAssessment-2009.pdf

Aspen Institute, Roundtable on Community Change. (2005). Understanding structural racism and promoting racial equity.

Association for Maternal and Child Health Programs Innovation Hub. (n.d.). Infant-Toddler Court Teams (based on the Safe Babies Court TeamTM Approach). www.amchpinnovation.org/database-entry/infant-toddler-court-teams-based-on-the-safe-babies-court-team-approach

Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet, 389, 1453–1463.

Bass, S., Shields, M., & Behrman, R. (2004). Children, families, and foster care: Analysis and recommendations. The Future of Children, 14(1), 5–29.

Casanueva, C., Harris, S., Carr, C., Burfend, C., & Smith, K. (2017). Final evaluation report of the Quality Improvement Center for Research-Based Infant-Toddler Court Teams. ZERO TO THREE.

Casanueva, C., Harris, S., Carr, C., Burfend, C., & Smith, K. (2019). Evaluation in multiple sites of the Safe Babies Court Team approach. Child Welfare, 97(1), 85–107.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2016). Applying the science of child development in child welfare systems. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/child-welfare-systems

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2021). Moving upstream: Confronting racism to open up children’s potential. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/moving-upstream-confronting-racism-to-open-up-childrens-potential

Center for the Study of Social Policy. (2015). Strategies to reduce racially disparate outcomes in child welfare. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Strategies-to-Reduce-Racially-Disparate-Outcomes-in-Child-Welfare-March-2015.pdf

Center for the Study of Social Policy. (2021, May). Strengthening Families: Increasing positive outcomes for children and families. https://cssp.org/our-work/project/strengthening-families

Center for the Study of Social Policy. (n.d.). Race Equity Impact Assessment. https://cssp.org/resource/race-equity-impact-assessment-tool

Center for Urban and Racial Equity. (n.d.). Website. http://urbanandracialequity.org

Chambers, R. M, Brocato, J., Fatemi, M., & Rodriguez, A. Y. (2016). An innovative child welfare pilot initiative: Results and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 143–151.

Chen, Y, & Thomson, D. (2021). Child poverty increased nationally during COVID, especially among Latino and Black children. Child Trends. www.childtrends.org/publications/child-poverty-increased-nationally-during-covid-especially-among-latino-and-black-children

Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2016). Racial disproportionality and disparity in child welfare. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/racial_disproportionality.pdf

Children’s Bureau. (2021). Child maltreatment 2019. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2019

Children’s Defense Fund. (2021). The state of America’s children 2021. www.childrensdefense.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-State-of-Americas-Children-2021.pdf

Citrin, A., Anderson, S., Martinez, V., Lawal, N., & Houshyar, S. (2021). Supporting the first 1,000 days of a child’s life: An anti-racist blueprint for early childhood well-being and child welfare prevention. Center for the Study of Social Policy. https://cssp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Supporting-the-First-1000-Days-of-a-Childs-Life.pdf

Cunningham, M. K., Gillespie, S., & Batko, S. (2019). How housing matters for families. Urban Institute. www.urban.org/research/publication/how-housing-matters-families/view/full_report

Derezotes, D., Poertner, J., & Testa, M. (Eds.). (2005). Race matters in child welfare: The overrepresentation of African-American children in the system: The Race Matters Consortium. Child Welfare League of America.

Duran, E., Long, P., Smith, B., & Stanley, T. (2005). From historical trauma to hope and healing: 2004 Appalachian Studies Association Conference [with Responses]. Appalachian Journal, 32(2), 164–180.

Evans, M. K. (2020). Covid’s color line—Infectious disease, inequity, and racial justice. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(5), 408–410.

Forde, A. T., Crookes, D. M., Suglia, S. F., & Demmer, R. T. (2019). The weathering hypothesis as an explanation for racial disparities in health: A systematic review. Annals of Epidemiology, 33, 1–18.

Foronda, C., Baptiste, D., Reinholdt, M., & Ousman, K. (2016). Cultural humility: A concept analysis. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(3), 210–217.

Gallion, J., & Citrin, A. (2021, February). Palm Beach County, 15th Judicial Circuit Early Childhood Court Race Equity: Session Three. [Powerpoint Presentation].

Ganasarajah, S., Siegel, G., & Sickmund, M. (2017). Disproportionality rates of children of color in foster care (Fiscal Year 2015). National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges.

Geronimus, A. T., Hicken, M., Keene, D., & Bound, J. (2006). “Weathering” and age patterns of allostatic load scores among Blacks and Whites in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 96(5), 826–833.

Ghosh Ippen, C., Norona, C. R., & Thomas, K. (2012). From tenet to practice: Putting diversity-informed services into action. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 33(2), 23–28.

Harris Professional Development Network Child Welfare Committee. (2019). Meaningful family time suite of resources. Irving Harris Foundation. www.irvingharrisfdn.org/meaningful-family-time

Hayes-Greene, D., & Love, B. (2018). The groundwater approach: Building a practical understanding of structural racism. The Racial Equity Institute. www.racialequityinstitute.com/groundwaterapproach

Hudson, L. (2017). Family time: Parent-child contact when the child is in foster care. In L. Hudson, A guide to implementing the Safe Babies Court Team approach (pp. 1–26). ZERO TO THREE.

Keating, K., Cole, P., & Schneider, A., with Schaffner, M. (2021). State of babies yearbook: 2021. ZERO TO THREE.

Leathers, S. (2002). Parental visiting and family reunification: How inclusive practice makes a difference. Child Welfare, 81(4), 595–616.

Lewis, M. L. (2012). Culture and trauma. In C. Figley (Ed.), The encyclopedia of trauma: An interdisciplinary guide. Sage.

Lewis, M. L. & Ghosh Ippen, C. (2004). Rainbows of tears, souls full of hope: Cultural issues related to young children and trauma. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Young children and trauma: What do we know and what do we need to know? (pp. 11–46). Guilford Press.

Lewis, M. L., Gray, E. S., & Bentley-Johnson, D. R. (2011). Training on healing from the historical trauma of slavery. Judges Letter, 5, 3–6.

Martin, M., & Connelly, D. (2015). Achieving racial equity: Child welfare strategies to improve outcomes for children of color. Center for the Study of Social Policy.

Minoff, E. (2018, October). Entangled roots: The role of race in policies that separate families. Center for the Study of Social Policy. https://cssp.org/resource/entangled-roots

Osofsky, J. D., Cohen, C., Huddleston, J., Hudson, L., Zavora, K., & Lewis, M. (2017). Questions every judge and lawyer should ask about infants and toddlers in the child welfare system [Technical Assistance Brief and Bench Card]. National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges and ZERO TO THREE. www.ncjfcj.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NCJFCJ_ZeroToThree_Questions_Final.pdf

Osofsky, J. D., Kronenberg, M., Hammer, J. H., Lederman, C., Katz, L., Adams, S., Graham, M., & Hogan, A. (2007). The development and evaluation of the intervention model for the Florida Infant Mental Health pilot program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(3), 259–280.

Quality Improvement Center for Research-Based Infant Toddler Court Teams. (2016). From standard to practice: Guiding principles for professionals working with infants, toddlers, and families in child welfare. ZERO TO THREE.

Racial Equity Institute. (n.d.). Website. www.racialequityinstitute.com

Shonkoff, J. Slopen, N., & Williams, D. (2021) Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and he impacts of racism on the foundations of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42, 115–134.

Smariga, M. (2007). Practice & policy brief: Visitation with infants and toddlers in foster care: What judges and attorneys need to know. ZERO TO THREE and the American Bar Association Center on Children and the Law.

Sotero, M. (2006). A conceptual model of historical trauma: Implications for public health practice and research. Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, 1(1), 93–108.

Summers, A. (2015). Disproportionality rates for children of color in foster care (fiscal year 2013). www.ncjfcj.org/publications/disproportionalityrates-for-children-of-color-in-foster-care-fiscal-year-2015

Sweetland, J. (2021). Reframing childhood adversity: Promoting upstream approaches. Frameworks Institute. www.frameworksinstitute.org/publication/reframing-childhood-adversity-promoting-upstreamapproaches

Wells, S. J. (2011). Disproportionality and disparity in child welfare: An overview of definitions and methods of measurement. In D. K. Green, K. Belanger, R. G. McRoy, & L. Bullard (Eds.), Challenging racial disproportionality in child welfare: Research, policy, and practice (pp. 3–12). CWLA Press.

Wilkinson, A., Laurore, J., Maxfield, E., Gross, E., Daily, S., & Keating, K. (2021). Racism creates inequities in maternal and child health, even before birth. Child Trends and ZERO TO THREE. https://stateofbabies.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/ZTTRacismInequitiesMaternalChildHealth_ChildTrends_May2021.pdf

Williams, D. R., & Wyatt, R. (2015). Racial bias in health care and health: Challenges and opportunities. JAMA, 314, 555–556.

ZERO TO THREE. (2020). The 2-4-2 Book Program: Promoting and strengthening parent-child relationships. https://www.zerotothree.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/The-2-4-2-Book-Program.pdf

ZERO TO THREE. (2021). The American Rescue Plan addresses 5 critical needs for babies. www.zerotothree.org/resources/3921-american-rescueplan-addresses-5-critical-needs-for-babies

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.-a). Equity and social justice in child welfare. www.zerotothree.org/resources/3057-equity-and-social-justice-in-child-welfare

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.-b). The Safe Babies Court TeamTM approach. www.zerotothree.org/resources/services/the-safe-babies-court-team-approach