Gina DelJones, The Center for Great Expectations, Somerset, New Jersey; Hannah Pomales, Rutgers University; Erica Y. Rodriguez, The Center for Great Expectations, Somerset, New Jersey; Alicia Mendez and Emily Bosk, Rutgers University; and Michael J. MacKenzie, McGill University

Abstract

A trauma-informed organization serving young children and their families experienced differentials in vaccine uptake. Organization leadership viewed this response through a trauma-informed framework that recognizes legacies of scientific racism and attendant distrust of medical information, particularly new treatments. Trauma-informed frameworks require sensitive organizational responses to address issues of vaccine hesitancy, as organizations set policies to balance the risks of re-traumatization with the risks to everyone’s physical health. This agency considered it an ethical imperative to support efforts to increase vaccination rates to protect clients and staff from COVID-19 infection as part of its official charge, while also balancing the experiential reality that many minoritized and marginalized communities face in reference to mistrust of U.S. health care policies.

Vaccine uptake—which refers to the proportion of a population that has received a specific vaccine—among staff and clients represents an issue of critical importance to mental health agencies, particularly those that provide residential treatment. Ensuring physical safety while also embracing principles of trustworthiness, collaboration, and empowerment are fundamental to the provision of trauma-informed care. These principles come into tensions with one another around the issue of vaccine uptake in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The contagiousness of COVID-19 creates physical risks for clients and staff alike, particularly those that have underlying physical health conditions that may make them more vulnerable to infection or severe courses of illness. At the same time, strategies to ensure physical safety such as requiring vaccination may contradict tenets of trauma-informed care related to safety, trustworthiness, collaboration, choice, and empowerment (Fallot & Harris, 2015). Trauma-informed agencies, particularly mental health agencies, can play a role in addressing vaccine hesitancy among both their clients and their staff. In this article, we detail our agency’s approach to increasing vaccination rates in a manner consistent with the principles of trauma-informed care.

As many as 5–10% of individuals identified as having strong anti-vaccination convictions pre-COVID-19, and even more were considered to be “vaccine hesitant” (Dubé et al., 2013). The COVID-19 pandemic, combined with existing and subsequent polarization around the use of vaccines in the US have highlighted and amplified issues related to anti-vaccination positions in health care settings.

Vaccine Hesitancy

According to the World Health Organization, vaccine hesitancy is defined as “a delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccination despite availability of vaccination services” (MacDonald, 2015, p. 4161). Reasons behind vaccine hesitancy vary, ranging from distrust of medical professionals to inaccurate information about vaccine risks (MacDonald, 2015). Low vaccine uptake among staff within mental health and residential behavioral health agencies may pose an even greater risk. People with severe mental health concerns are at a heightened mortality rate due to COVID-19 (Wang et al., 2021). Further, recent studies indicate that people living with substance use disorder have high levels of vaccine hesitancy, with approximately half expressing hesitancy (Mellis et al., 2021). At the same time, rates of substance use re-occurrence have also increased during the pandemic as people grapple with the social, economic, and physical stressors of lockdowns, creating more demand for treatment. Thus, behavioral health and substance use residential agencies may be confronted with an ethical dilemma of addressing individual beliefs held by staff and clients about vaccines, while making decisions about preventative guidelines to protect staff and higher risk clients. Studies show that some individuals may choose to receive one vaccine over another or eventually choose vaccination while still being hesitant (Jacobson et al., 2015). These studies create reason to be optimistic that, with support and exploration, people can be assisted in accepting vaccination regimens about which they may have initially been hesitant.

The contagiousness of COVID-19 creates physical risks for clients and staff alike, particularly those that have underlying physical health conditions that may make them more vulnerable to infection or severe courses of illness. Photo: shutterstock/DisobeyArt

In January 2021, a COVID-19 vaccine became available to all staff at a substance use and behavioral health agency providing two inpatient “mommy and me” residential homes, an on-site early childhood education center for children 6 weeks to 3 years old, outpatient services, and in-home services. The Center for Great Expectations (CGE) has approximately 115 staff and serves around 450 adults and children per year. The agency contracted with a local pharmacy to provide three vaccination clinics on-site over a 6-week period. Uptake of the vaccine, however, was low initially, with only 39% of staff signing up to receive a vaccine.

The low uptake was of significant concern because of the implications for creating a safe physical environment for all by limiting the transmission of COVID-19, particularly in the residential treatment setting. The internal research team tracking staff vaccination rates was aware that vaccine hesitancy was likely rooted in multiple contributing factors that needed to be addressed. While it was not disclosed who did and did not receive the vaccine, the administration expressed concern about extremely low uptake from most frontline staff who, as a group, have a much higher percentage of women, is mostly comprised of people of color, and with lower education levels than administrative staff.

A Trauma-Informed Framework to Understand and Respond to Low Vaccine Uptake

CGE is a trauma-informed organization, and differentials in vaccine uptake in staff members can best be understood through a trauma-informed framework that recognizes the legacies of scientific racism and the attendant distrust of medical information, particularly new treatments, that are carried into the present day. A stress-response framework further extends our understanding of vaccine hesitancy in a way that is consistent with trauma theory. Living in a pandemic has broad impacts on almost every individual that has heightened stress. Cognitive load theory postulates that there is a limited capacity to working memory, which can be overloaded when presented with too much information (Sweller, 2011). A combination of chronic stress and being inundated with competing or negative messages and disinformation about vaccines (Wardle & Singerman, 2021; Wilson & Wiysonge, 2020) on social media has made decision-making about vaccines more difficult. It is arguable that “people experiencing communication and information overload have less cognitive resources at their disposal, which hinders their ability to verify the information they encounter” (Islam et al., 2020, p. 6). For those who are hesitant about vaccination, there is likely little extra bandwidth for learning about a new disease and its vaccine development or seeking out trustworthy sources that can deliver accurate information.

A trauma-informed framework requires sensitive organizational responses to addressing issues of vaccine hesitancy among staff and clients alike as organizations set policy to balance risks of re-traumatization with risks to everyone’s physical health. The current context also presented to trauma-informed organizations an opportunity to model, through sensitive, supportive, and affirming approaches with staff, the very forms of interaction that the spirit of the model calls for in staff work with clients as well. CGE considered the ethical imperative to support efforts to increase vaccination rates to protect clients and staff from COVID-19 infection as part of its official charge, while also balancing the experiential reality that many minoritized and marginalized communities face in reference to mistrust of U.S. health care policies.

While debates continue in the field and in the literature on the proper balance in vaccine promotion of incentive strategies and mandates (Volpp et al., 2020), a calculus which may be further contextually dependent for the breadth of needs of different social service providers, CGE elected to implement a promotive approach that would be consistent with the principles that guide trauma-informed practice, and the organization elected not to impose a mandate. Drawing on community-based participatory research (Reid & Brief, 2009), the department considered the following questions in relationship to the need to address issues related to scientific racism, staff stress, and misinformation related to vaccine hesitancy:

- What is the best method to provide information (i.e., e-mail, flyer)?

- What type of information is useful and relevant (i.e., articles, videos, and websites)?

- How are concerns that involve issues of social justice and systemic racism addressed?

- What is the best practice to providing this information?

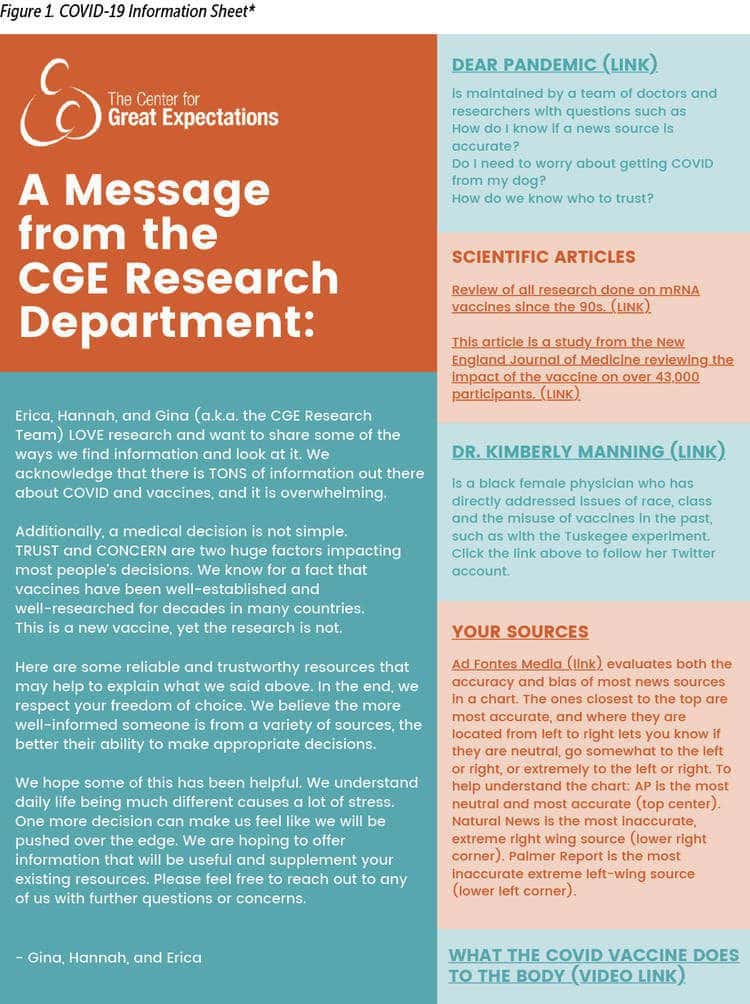

Consistent with a trauma-informed organizational approach, the priority was to maintain strong relationships between the agency’s supervisor and supervisee staff. Using the questions listed previously as a guide, the research department designed an information sheet that first validated potential concerns, contextualized the history of scientific racism, emphasized an employee’s right to make their own choices with regard to their health, and then provided a list of resources from nonbiased sources.

COVID-19 Vaccine Information Sheet

The information sheet (see Figure 1, p. 14; links in the figure are included in the Learn More box) was formed using the five core tenets of trauma-informed care: safety, trustworthiness, choice, collaboration, and empowerment (Fallot & Harris, 2015).

- Safety was addressed through acknowledging concerns about vaccination, validating fears and contextualizing them within the legacy of historical trauma and scientific racism.

- Trustworthiness was addressed by including resources about how to discern reliable sources of information for a range of reading levels and by providing a nonbiased information sheet and follow-up.

- Choice was supported by emphasizing that the decision was entirely up to the individual.

- Collaboration and empowerment were embedded throughout the document by offering resources, information, and support in talking through the decision.

The process of selecting which resources to include involved many hard discussions, with team members challenging each other about ideas which might be perceived differently by different audiences, scouring through many sites and publicly available vaccine-promotion videos from reliable sources to produce the final selection of resources. Wording of the letter was scrutinized, to continually refer to staff autonomy and choice, even though the team was unanimously in support of vaccination. The formatting and content are intentionally brief and approachable.

The agency contracted with a local pharmacy to provide three vaccination clinics on-site over a 6-week period. Photo: shutterstock/Russamee

To emphasize the core tenets of trauma-informed care, the research department included an explanation of the purpose of the flyer. The research department personally signed the email the information sheet was sent within, to ensure that employees who may have strong relationships with the research staff may be more inclined to read it. In the resources shared, the research department provided a link to the Twitter page of a prominent Black female physician who regularly provided scientific and medical information in clear and concise ways that were unbiased and educational. Research suggests that strong relationships between health care providers and patients are one of the most effective interventions to increase vaccination uptake (Bester, 2015). The research department believed it was important to provide a voice that was inclusive and reflective of the population this agency serves and employs.

The information sheet also included a link to “Dear Pandemic,” a pandemic information site run by an interdisciplinary all-woman team of researchers and clinicians, whose racial and cultural demographics are reflective of the agency’s staff and client population. On their website, they state that their mission is “to educate and empower individuals to successfully navigate the COVID-19 information overwhelm.” This site includes an easily searchable database for staff to look for additional information if they wish.

An additional resource was a link to a Media Bias Chart created by Ad Fontes Media, Inc., a public benefit corporation whose mission as stated on their website is “to make news consumers smarter and news media better.” The goal of including this site was to help staff members put their current sources of information in perspective of all media sources, in terms of how they rank on scales of accuracy to inaccuracy, as well as bias.

The research department understood that reading levels vary greatly among our staff, and some might not have their own news media sources. Therefore, another link included was a YouTube link that explains COVID-19 and how the vaccine works.

Lastly, the agency’s research department decided to provide scholarly articles linked to the science behind the COVID-19 vaccine. This information was provided to offer insight into the science that led to the development of such efficacious mRNA COVID-19 vaccines.

Results

After the dissemination of the information sheet, and prior to the second clinic, there was a 35% increase in registration for the COVID-19 vaccine. While the association between the introduction of the information sheet and the increased vaccine uptake is qualitative in nature and cannot be causally confirmed, it is suggestive of the role that organizational actions can play in supporting their frontline staff in decision-making about vaccination. Trauma-informed organizations can use the central tenets of this practice approach to facilitate conversations with staff about difficult topics.

A post flash-survey designed to take less than 60 seconds to complete was distributed through the organization-wide email, to all staff members, to capture qualitative impressions and feedback of the information sheet. The post-survey included questions regarding whether the staff member read the initial email containing the information flyer, whether they had decided about receiving the vaccination prior to the information sheet, if the sheet assisted them in making an informed decision about receiving the vaccination, and staff member impressions of the organization sending the vaccine information sheet to staff overall. Of the approximately 115 staff, 52 respondents completed the post-survey.

Responses to decision making:

- 16 selected “the information flyer assisted them in making a decision”

- 2 selected “the flyer did not help them make a decision about receiving vaccination”

- 13 selected “they had already made a decision about the vaccination prior to the information sheet, and the flyer did not further inform their decision regarding vaccination”

- 17 selected they “found the resources included in the sheet to be useful”

- 15 selected “they did not look at the resources on the flyer”

Impressions of receiving the information sheet:

- 31 selected “it was helpful”

- 7 selected “they were surprised”

- 3 selected “it was judgmental”

- 2 selected “the research department should not be involved with staff decisions and only client-related issues”

A trauma-informed framework requires sensitive organizational responses to addressing issues of vaccine hesitancy among staff and clients. Photo: shutterstock/fizkes

Notably, the staff members who reported that the information sheet was either judgmental or that the research team should not be involved with staff decisions all indicated that they did not read the initial email in which the information sheet was sent. It is possible that although they did not read the information sheet email, the staff members expressed their feelings about the concept of the research team providing information about the vaccine, generally speaking. In addition, the post-survey did not probe further regarding the response of “surprised.” As such, it can be postulated that some staff respondents were surprised to receive the information sheet from the CGE Research Team, whereas other respondents may have been indicating they were surprised by the information within the flyer itself.

In line with a trauma-informed approach to acknowledging vaccine hesitancy, the post-survey was written in a way to normalize all final decisions and the individual’s autonomy. Some multiple-choice answers included “Yes, it helped me decide to NOT to get the vaccine,” as well as “The research department should not be involved with staff decisions, only client-related issues.” Validating autonomy of choice means the choice may not be the “desired” one. It was important to the agency and the research department to validate staff members’ independence and to embrace the truth without fear of repercussion.

The feedback provided by staff members indicates that organizations can support decision-making among staff by promoting vaccination uptake within an empowerment framework. Responses also suggest that the information sheet empowered staff members to make a decision—either to vaccinate or not—by providing sensitive, specific, and accurate materials about vaccinations that acknowledged legacies of mistrust and scientific racism to support staff in formulating decisions about their health.

Limitations

It should be noted, that of the 13 staff members who made a vaccination decision prior to the information sheet distribution, the post-survey did not specify whether or not the respondents’ decision was to receive the vaccine or not. Also, there is a limitation regarding the specific utility indicated by the staff members, above and beyond making an informed decision about receiving the vaccination themselves. It may be possible that staff members used resources embedded within the information sheet to consider how to approach evidence-based resources with other subjects outside of the scope of the COVID-19 vaccination, and it is also possible that other aspects of the information sheet were useful among staff. This follow-up information was not captured at this time.

Practice Implications

This work demonstrates one way in which trauma-informed organizations can use the central tenets of this approach to facilitate conversations with staff surrounding difficult or sensitive topics. Currently, debates about vaccination and staff center around a binary: Should organizations require vaccination as a condition of employment? There is a third way, with organizations supporting discussion and decision-making that may promote vaccination uptake within a trauma-informed framework that emphasizes an empowerment approach. The information sheet represents one strategy, but there are also others: hosting conversations about vaccine concerns between staff and knowledgeable medical professionals who reflect the demographics of staff and holding staff-wide discussions about the implications of low vaccination rates. Encouraging staff involvement to address organizational concerns and policies through a collaborative, working relationship between the research team and staff invites staff to provide feedback. Beyond this particular survey, this approach may be beneficial to implement as a way for organizations to support their employees; receive critical feedback and details on their experiences from their staff; and to facilitate a workplace environment that promotes autonomy, trust, safety, and collaboration.

The flyer in Figure 1 includes the following links:

Dear Pandemic, a website created by an interdisciplinary all-woman team of researchers and clinicians with expertise including nursing, mental health, demography, health policy/economics, and epidemiology. link

Article reviewing 3 decades of research on mRNA vaccines link

New England Journal of Medicine on safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine link

Dr. Kimberly Manning, Professor of Medicine and Associate Vice Chair, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, Emory University link

Ad Fontes Media Bias Chart plink] (https://adfontesmedia.com/static-mbc)

ASAPScience: What COVID vaccine does to body link

Author Bios

Gina DelJones, MSW, LSW, is the clinical research manager for The Center for Great Expectations, which offers trauma-informed substance abuse and mental health disorder treatment in New Jersey through six different programs. Guiding the core of our work is both the ARC Model (Attachment, Regulation and Competency) as well as the Trauma C.A.R.E.© Model, a trauma-informed model that strengthens the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, physical, and spiritual competencies of each client so that they can live meaningful lives. Ms. DelJones is devoted to improving current treatment methods for substance use clients through well-documented research, striving for thorough data that is reflective of the status of clients and using it to inform care and create best practices. Her degrees include a master’s in social work from Rutgers, focusing on the addiction counselor training program, and she holds a bachelor’s degree in developmental psychology and women’s studies with a minor in public health education from Rutgers College, at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey.

Hannah Pomales currently serves as the project director for the New Jersey Powerful Families, Powerful Communities Evaluation at Rutgers University School of Social Work. Through this project, Ms. Pomales is using qualitative/ethnographic and quantitative measures to evaluate organizational and programmatic restructuring to the current child welfare system in New Jersey, using a community-based participatory approach to amplify the voices of community members and stakeholders with lived experiences. In addition, Ms. Pomales is a research team member in the Rutgers University School of Social Work, and her current work centers on topics related to trauma-informed care best practices in social service and behavioral health agencies, child welfare, substance use treatment among pregnant and parenting people, and both infant and maternal mental health. Previously, Ms. Pomales has served as a research program coordinator for The Center for Great Expectation–Attachment, Regulation, and Competency (ARC) Program, as well as several other academic institutions including Fairleigh Dickinson University and Monmouth University. Her previous research has centered on social-justice concerns related to barriers to seeking mental health care among under-represented communities, experiences of Students of Color in anti-racism graduate counseling courses, and mental health help-seeking propensity related to adult attachment styles. She has also served as a mental health and substance use counselor, including at Rutgers University’s Collegiate Recovery Program for students living in recovery from substance use disorder, and numerous community-based counseling programs across the state of New Jersey. Ms. Pomales holds a bachelor’s degree in psychology and women’s and gender studies from Rutgers University–New Brunswick.

Erica Y. Rodriguez, MPA, worked for the Center for Great Expectations as research coordinator, advancing research in early relational health, trauma, and substance use. Previously, Ms. Rodriguez worked directly servicing families and adults experiencing homelessness by providing shelter and financial assistance. She also is a faithful volunteer teaching English to immigrant activists and advocating for human’s rights in the Northern Triangle (El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala). Ms. Rodriguez is an AmeriCorps VISTA alumnus, has a master’s degree in public administration, and a bachelor’s degree in communication studies.

Alicia Mendez, MSW, is a doctoral candidate of social work at Rutgers University. She is currently the project director for the Substance Use Trauma and Resilience (STAR) Lab. She has worked in program evaluation for more than 5 years, has led numerous campaigns to address racism within social work and higher education, and recently created a bachelor-level class called Confronting Anti-Black Racism, a social work meets literature class aimed at teaching students how to advocate against racism while simultaneously understanding the nuance and complexities of Blackness in America as written by Black and African authors and scholars.

Emily Bosk, PhD, is an assistant professor of social work and a faculty affiliate with the Institute for Health, Health Policy, and Aging Research; the Center for Violence Against Women and Children; and the Department of Sociology. Trained as both a sociologist and a clinical social worker, Dr. Bosk works at the intersection of social theory and applied practice. Her research uses rigorous social science methods to theorize how organizations and individuals understand and intervene with vulnerable children and families and to trace out the policy and practice implications of these approaches. Current research includes: analysis of standardized decision-making in child welfare at the individual, organizational, and policy levels; parenting and substance use disorders; trauma-informed care, and programs to support parent–child relationships. Dr. Bosk has held fellowships in The Prevention of Child Maltreatment and the Promotion of Child Wellbeing through the Doris Duke Foundation and in clinical social work in the Intensive In-Home Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Services Division at the Yale Child Study Center. Her work has been funded by grants from The National Science Foundation, the Kellogg Foundation, and the Fahs-Beck Fund for Research and Experimentation. Committed to translating her research for policymakers and practitioners, Dr. Bosk has provided consultation to child welfare agencies in several states and regularly collaborates with community agencies in New Jersey.

Michael J. MacKenzie, PhD, is the Canada Research Chair in Child Well-Being and professor of social work and pediatrics at McGill University. Dr. MacKenzie is also a member of the ZERO TO THREE Academy of Fellows. His decades of work in out-of-home care with children whose early childhood experiences had profoundly shaped the course of their lives sparked his passion for improving family- and community-based supports for maltreated children. These experiences also focused his efforts on better understanding the dynamic connections between the biological and social worlds of the developing child. Dr. MacKenzie’s focus is on the accumulation of stress, adversity, and trauma in early childhood and the impact on parenting, including the roots of harsh parenting and the pathways of children into and through the child welfare system. Dr. MacKenzie was honored as a William T. Grant Foundation Faculty Scholar and has also been recognized with the Excellence in Research Award from the Society for Social Work and Research. Dr. MacKenzie holds a bachelor’s degree in biology and master’s degree in molecular genetics from the University of Western Ontario, and a master’s of social work, master of arts, and joint doctorate in social work and developmental psychology from the University of Michigan.

Suggested Citation

DelJones, G., Pomales, H., Rodriguez, E. Y., Mendez, A., Bosk, E., & MacKenzie, M. J. (2022). Vaccine hesitancy and trauma-informed care: Developing a sensitive organizational response. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 42(3), 11–18.

References

Bester, J. C. (2015). Vaccine refusal and trust: The trouble with coercion and education and suggestions for a cure. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 12(4), 555—559.

Dubé, E., Laberge, C., Guay, M., Bramadat, P., Roy, R., & Bettinger, J. A. (2013). Vaccine hesitancy: An overview. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 9(8), 1763–1773. doi:10.4161/hv.24657

Fallot, R. D., & Harris, M. (2015). Creating cultures of trauma-informed care: A self-assessment and planning protocol. 10.13140/2.1.4843.6002.

Islam, A. K. M. N., Laato, S., Talukder, S., & Sutinen, E., (2020). Misinformation sharing and social media fatigue during COVID-19: An affordance and cognitive load perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 159.

Jacobson, R. M., Sauver, J. L. S., & Rutten, L. J. F. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(11), 1562–1568.

MacDonald, N. E. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161–4164.

Mellis, A. M., Kelly, B. C., Potenza, M. N., & Hulsey, J. N. (2021). Factors associated with drug overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 1:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000816. doi: 10.1097/ ADM.0000000000000816. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33534278; PMCID: PMC8325711.

Reid, C., & Brief, E. (2009). Confronting condescending ethics: How community-based research challenges traditional approaches to consent, confidentiality, and capacity. Journal of Academic Ethics, (1–2), 75.

Sweller, J. (2011). Cognitive load theory. In J. P. Mestre & B. H. Ross (Eds.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education (pp. 37–76). Elsevier Academic Press. link

Volpp, K. G., Loewenstein, G., & Buttenheim, A. M. (2020). Behaviorally informed strategies for a national COVID-19 vaccine promotion program. JAMA, 325, 125–126.

Wang, Q., Xu, R., & Volkow, N. D. (2021). Increased risk of COVID-19 infection and mortality in people with mental disorders: Analysis from electronic health records in the United States. World Psychiatry, 20(1), 124–130.

Wardle, C., & Singerman, E. (2021). Too little, too late: Social media companies’ failure to tackle vaccine misinformation poses a real threat. BMJ, 372, n26.

Wilson, S. L., & Wiysonge, C. (2020). Social media and vaccine hesitancy. BMJ Global Health, 5, e004206.