AANHPI Thought Leaders Advancing Diversity-Informed Practice

Knowing your value. Speaking your truth. Practicing humility. Being confident yet compassionate in your work. These are just a few key pieces of advice our power list of experienced and inspirational early childhood professionals have for others in the field.

Learn more about their perspectives and how their Asian American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander heritage influences their approach to diversity-informed practice and the services they provide to young children and their families.

Higher education and training don’t mean a thing to families if you are not being authentic – lean into bringing your own cultural background into your work.

Erin Henderson Lacerdo

Erin Henderson Lacerdo, LCSW, IMH-E®

Executive Director, Association for Infant Mental Health in Hawai'i

Erin grew up in Kunia, O’ahu and believes that everyone has a “kuleana,” or responsibility, in shaping the future because every time we interact with another person, it has the ability to provide support to the next generation.

To me, the key is not “knowing” the nuances of different cultures, but coming from a place of humility, curiosity, and respect. The best way I’ve heard the term “indigenous” defined is “that which has endured over time” – and that has reframed my own thinking in terms of what indigenous means. Each culture has something that is indigenous. What is yours? And what does that mean to someone who has a different cultural background? Perhaps we will even find that people of the same cultural background have quite different practices. That to me, is the beauty of wondering with someone – what experiences have made you who you are today? And what pieces of you are missing? What pieces do you grieve for?

Something early childhood professionals sometimes miss is that these early years are our opportunity to lay the groundwork for ALL things that come in life – including culture. How does the curriculum you use reflect the faces of the children in your program? How can you integrate their languages, celebrations, practices into the questions you ask the children and their families? How are you honoring their family traditions? We don’t have to know the culture to be respectful of it. Being grounded in one’s culture is a protective factor from what I have seen – and the more we can support that connection early in life, the more rooted that child and family will be through the years.

Intentional. Adaptive. Hopeful.

There simply aren’t enough of us! It’s important for our communities to trust and build relationships with providers, and there is always something comforting when families can feel connected to their provider. There will be times when the dominant or mainstream thinking in the field goes against what you know to be true based on your own experience. Higher education and training don’t mean a thing to families if you are not being authentic – lean into bringing your own cultural background into your work. Families will welcome hearing how they can still be who they are and be the best parents for their children.

Walking home from school and buying ice cake with li hing mui from some aunty in her garage. We call them the “hanabata days.”

Investing in early childhood has the potential to improve generations to come in ways that we will not be able to see in our own lifetimes – and the investment is worth the hard work.

Sufna John

Sufna John, PhD

Child-Parent Psychotherapy (CPP) and DC:0-5 Trainer

Sufna is a licensed psychologist and associate professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences in Little Rock, Arkansas. She is an Indian American mother of two biracial children, and strives to provide infant and early childhood mental health services through a lens of diversity, equity and inclusion.

Just as children develop within the context of relationships, families develop within the context of their culture. Someone’s cultural background, lived experiences, and associated values shape such important aspects of who they are – ways they parent, hopes and dreams for their children, their approach to accessing your services, and what strengths they bring to your work together.

Cultural humility is not just about the client, it is also about the way a professional understands their own identities and how their culture shapes the work they do with the wide range of families they serve. Families deserve the best we have to offer and true collaboration means that we honor a family’s cultural background in all aspects of care – from the questions we ask to the goals we set and strategies and supports we provide. I have shied away from using the term cultural competence here because it may accidentally imply that this is a “competency” that we build and then the work is done. Instead, I prefer the term cultural humility because it embodies the notion that doing this work is the task of a lifetime, in which we continuously strive to better understand ourselves and the clients we serve.

Benevolent: I center my practice in the sincere belief that people typically do the best they can with what they know and what their environment allows them to do. This grace for others helps me to approach people with a strengths-based mindset, stay better regulated, and make more intentional decisions.

Curious: I hope to remain open to various points of view and align my behavior with the notion that there is rarely a single “right” answer or way of understanding a situation.

Reflective: In line with the strong roots of reflection in infant and early childhood mental health, I believe that who you are and how you do is just as important as what you do in your work. Valuing refection has meant welcoming opportunities to slow down with others and intentionally explore the choices we make and how our work impacts us. Reflective spaces feel very congruent with my own collectivist cultural background as an Indian American woman – in which we believe we are best when tied to our community. Reliance on others, in this way, is a sign of strength and commitment to your own betterment and the betterment of those around you. I feel like my truest self when in reflective spaces.

Embrace all of who you are as an important part of what you do. When possible, try to speak your truth in moments in which your upbringing and cultural background provide a counterpoint to the dominant narrative. I acknowledge that this is aspirational and that it is not always possible or safe to speak up. Yet, the ever-optimist in me feels driven by the notion that we are truly our ancestors’ wildest dreams and we owe it to ourselves, and our communities, to be our full selves. You belong in this work and our field needs your truth to keep growing in its ability to meet the needs of all people.

Eating ice cream with my family after dinner each night. This ritual of love and care was so natural to me that I genuinely was stunned when I got to college and realized all people don’t eat dessert every night. This nurturance – this way that love was embodied in my family – is something I hold dear and now do with my own children each night (though admittedly, we tend to favor cookies over ice cream).

Know that you are worthy! Take cultural pride, express yourself, and celebrate your accomplishments in the workplace. If you do not, you will be easily dismissed and stay invisible.

Kyong-Ah Kwon

Kyong-Ah Kwon, PhD

Drusa B. Cable Endowed Chair in Education, Rainbolt Family Endowed Education Presidential Professor, Associate Professor, and Principal Investigator of the Happy Teacher Project, University of Oklahoma

Kyong-Ah Kwon is a third generation of teachers in her family and has taught young children in both Korea and the U.S.. She has served as a principal investigator and leader of the Happy Teacher Project on early childhood teachers’ well-being.

There is no doubt cultural competence is one of the key ingredients of high-quality early care and education and services. Typically, parents of infants and toddlers prefer their family (e.g., grandparents) and early childhood professionals whose personal and cultural backgrounds are similar to theirs (e.g., race/ethnicity, language, educational level) because they trust them. Parents would also find it easier to communicate with them and expect that they would understand the family’s needs better.

Regardless, especially for those who do not have similar cultural backgrounds, it is a vital first step for professionals to be open-minded and curious about the family and cultural backgrounds to get to know each child and his/her strengths and needs and make extra efforts to do so. Families should have the opportunity to share their cultural values and beliefs, goals and expectations for their child, and any concerns and questions they might have on a regular basis throughout the year. This is particularly important for professionals working with infants and toddlers as children at this age rely on adults’ care and understanding and would not be able to express their needs, likes, and dislikes as clearly as older children. Strong cultural connections and understanding would lay an important foundation for trusting relationships between professionals and families. This will effectively reduce the feeling of guilt and anxiety parents would have when leaving their child in non-parental care or services. Children who are cared for by teachers who are culturally competent and provide culturally responsive care would feel comfortable and accepted and thrive as a competent and self-regulated child.

Interdisciplinary. Collaborative. Persistent.

It has been 22 years since I moved to the U.S. to further my education and receive my doctoral degree in the U.S. as an Asian immigrant. While I am blessed to meet and work with many kind people, I have seen many AAPI, including myself, experience discrimination, microaggressions, stereotyping, and hate crimes, and we often suffer in silence under pressure as a model minority group. From my experiences, I have a few things to share as words of affirmation for the AAPI professionals working with young children.

First, share your cultural heritage with children and families. Culturally responsive practice is about mutual understanding and exchange between professionals and children and families. While listening to, respecting, and embracing the cultural expectations and traditions of the children and families you work with, it is equally important to share your own cultural heritage and values with them. This enhances clear two-way communication and promotes strong partnerships.

Second, know that you are worthy! Take cultural pride, express yourself, and celebrate your accomplishments in the workplace. Due to humility as a traditional virtue, especially in a Confucian heritage culture, we Asians are encouraged to be humble and are discouraged to brag about our accomplishments. However, if you do not, you will be easily dismissed and stay invisible. You have so many cultural assets, such as your home language and different perspectives and cultures to enrich children’s experiences and diversify the workplace. Children will also learn from you how to build a positive cultural identity and embrace self-worth.

Third, don’t be afraid of leading others. AAPI are hard-working, competent, and responsible, but I have not seen many Asians taking a leadership role. Lastly, speak up when you witness and experience unjust treatment and racism in any form. Make an ally and take a strong stand against racism, including anti-Asian racism, in the workplace and in your community. Children will learn how to step up for themselves and treat others fairly.

My grandmother and my mother were elementary school teachers, and my mother always told me that I would be the third generation of teachers. I could not resist and here I am. In fact, I loved my teacher and friends, engaged in various pretend plays (I always played mom), and rode a very cool-looking indoor slide in a preschool. I even liked naptime and still remember how soft and cozy the pink flower-patterned mattress was. My mom said every morning when she woke up, she found me fully dressed up in a preschool uniform waiting at the door ready for school. I loved my experiences in preschool so much that I made a decision for teaching young children as my life-long career at age 5 and never changed my mind since then.

I worked with young children for 7 years in Korea and immigrated to the U.S. to learn to be a better teacher. I am thankful for my preschool teacher, Ms. Kim, who leaves unforgettable memories with me and shaped me into who I am now as a passionate teacher, teacher educator, and researcher.

Being valued for who and how I am is significant, it parallels how we want children to feel – supported and valued for who they are.

Katrina Macasaet

Katrina Macasaet

Senior Manager, Professional Development, ZERO TO THREE

Katrina leads our Critical Competencies for Infant-Toddler Educators™ and The Growing Brain professional development programs. She grew up in the Philippines and is proud to bring her lived experience as an Asian American to the work she does on behalf of young children.

Diversity-informed practice begins with understanding ourselves and the reciprocal relationships in our work, how our work impacts the lives of young children and their families, and how their experiences impact us and our work. It helps us approach the work through a lens of curiosity and recognize that we cannot filter the experience of children and families through just our own singular lens.

Community, collaboration, and communication. I chose these because together, they support opportunities to create impactful and lasting change. We are most effective together in a collaborative community that welcomes honest and respectful communication.

Surround yourself with people who celebrate who you are and the unique aspects that you bring to the work. Being Asian-American is a big part of who I am. I am fortunate to be part of a team that celebrates when I bring this part of myself into the work but does not box me into that aspect of my identity as defining all that I am. Being valued for who and how I am is significant, it parallels how we want children to feel – supported and valued for who they are. It is difficult at best to make others feel valued, especially children, if you feel undervalued yourself.

Humility helps us remember that the families’ stories and children’s emerging skills carry as much weight as our professional training.

Nat Vikitsreth

Nat Vikitsreth, LCSW, DT, CEIM

Founder, Come Back to Care

Nat is a clinical psychotherapist and child development specialist who founded Come Back to Care to collaborate with parents in intergenerational family healing. She is a Thai-Chinese Asian American who infuses her ancestral and cultural knowledge into her work with families.

There’s a phrase in Thai, my mother tongue, “Tua Mae,” which colloquially describes someone who knows their craft wholeheartedly and practices it fiercely. When I see early childhood professionals with cultural competence, they’re the real deal or “Tua Mae” and I can’t help but smile at them in admiration.

With cultural competence, we show up to families and children with humility, audacity, and- dare I say- joy!

We need humility to fully be with the families and children we work with, and to remember that multiple truths exist. Humility helps us remember that the families’ stories and children’s emerging skills carry as much weight as our professional training.

We need audacity to de-center our Euro-American oriented professional training and widen the center to include voices that are pushed to the margins by the dominant norms. That means the audacity to compassionately agitate business as usual and ask “Why doesn’t our agency have more providers who look like the families we’re serving?” or “How can we adjust the workshop schedules to accommodate caregivers who work double shifts?”

Lastly the joy comes from continuously being a learner, from fumbling through our mistakes and making (lots of) repairs on our way to equity.

There’s never a dull moment in our early childhood work, right?

Decolonized. Embodied. Intergenerational.

Comfort isn’t the same as harmony. Blending in and people pleasing aren’t the same as belonging. Please trust your inner wisdom and discernment. You have SO much to offer to the families and children you’re working with.

Picking jasmine flowers with my grandmother for our ancestors’ altar.

When we cultivate our awareness and curiosity around how cultural values, beliefs, and norms shape the way feelings, ideas, needs, and concerns are held and expressed by the children and families we serve, we build bridges of understanding and pathways to empathy.

Esther Wong

Esther Wong, LCSW

Early Childhood Mental Health Clinician and Consultant, University of California, San Francisco, Infant-Parent Program

Esther provides trauma-informed and culturally sensitive program consultation in early education settings, as well as dyadic therapy services to young children and their families.

We are all cultural beings. All of our experiences, and the meanings we derive from them, are mediated by culture and our cultural contexts. How we think, feel, behave, and interact with others — and how we interpret the thoughts, feelings, and actions of others — all of this is anchored in and powerfully shaped by culture. When we cultivate our awareness and curiosity around how cultural values, beliefs, and norms shape the way feelings, ideas, needs, and concerns are held and expressed by the children and families we serve, we build bridges of understanding and pathways to empathy. We are less likely to jump to negative judgments and foregone conclusions about others’ capabilities and intentions. We are less likely to overly pathologize or individualize problems, which can really get in the way of efforts to unify around shared goals and form supportive, growth-promoting partnerships with those whom we serve. We discover new ways of understanding and appreciating the experiences of others and open ourselves up to new learning, growth, and renewed energy for our work.

Integrative. Collaborative. Responsive.

Know that you are an asset to the field and to the children and families you serve. If you have lived experience navigating between two or more cultures, of negotiating or attempting to reconcile cultural differences, of code-switching across settings, of immigrating to a new country or being a child of an immigrant, or of working to maintain family and community ties across long distances, you are particularly well-positioned to appreciate the experiences of others who are doing the same in a deep and nuanced way. The field can and should learn from us about ways that Western values, norms, and ways of thinking do not and cannot map onto non-Western cultures and that non-Western cultures have their own wisdoms, ways of knowing, and paths to healing that are fully legitimate and deserving of honor and respect. Whenever possible, seek out other AANHPI professionals in the field and build connections with them. There is strength and courage in solidarity.

When professionals are culturally competent, they open what’s called their “third eye” to see things from a cultural perspective, making them more likely to respond with grace and understanding.

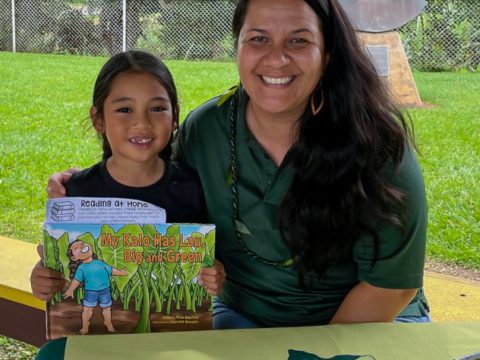

Pua Aquino

June "Pua" Aquino

Hawaiian Cultural Specialist, Partners in Development Foundation

As part of Partners in Development Foundation‘s Hawaiian Cultural Team, Pua works with families to navigate social challenges and grow self-resiliency and vibrancy and establish secure communities in Hawai’i.

It is vital for early childhood professionals to be culturally competent because not only does it help that person understand more about themselves, but it allows them to better understand their students. When professionals are culturally competent, they open what’s called their “third eye” to see things from a cultural perspective, making them more likely to respond with grace and understanding.

One of the best things we can do is learn more about our own culture and the different cultures of the families we serve. Find ways to create bridges between the families we serve in our classrooms and us.

My favorite childhood memory is when my mom took my younger twin brothers and me to a ranch near our house. We live on the west side of the island of Oʻahu in Hawai’i, where it is usually very dry most of the year. One weekend it rained for several days straight, so my mom told us we should go to the ranch to see if the stream there had water in it. We walked to the stream and saw there was water! We continued walking up the stream, where we finally came to a spot with a decent amount of water in it. We made a dam with some rocks, and there was enough water in it for us to float around and take a dip. I’ll never forget that day.