Home/Resources/Early Development/The Truck with the Large Shovel in the Front: A Lesson in Experiential Learning

The Truck with the Large Shovel in the Front: A Lesson in Experiential Learning

Author

Elizabeth Troisi

Early Childhood Educator

Elizabeth has twenty years of experience working with toddlers and three-year-olds. She is a graduate of Bank Street College of Education and works at a progressive nursery school on Roosevelt Island, in New York City. Her favorite part of working in the dynamic field of early childhood education is the opportunity for strong community engagement and following the children’s interests through emergent curricula. In her free time Elizabeth enjoys zine making and walking in the woods.

When the world changed and schools closed in March 2020, educators across the globe felt panic about how they would continue their work through a screen. Our work as early childhood educators felt even more under attack as it relies so heavily on hands-on experiences and the tangible relationships we hold with children and families.

We were advised to use screens for nearly all our important social engagement activities, including meeting, story, and play times. Even against our best judgments as educators — understanding that extended screen time was not recommended for young children — we relied upon screens to maintain our connections. There were times of joy and hope during this process, but also many moments of fear, sadness, and disconnection. When our school opened again in September 2020, the children in our class, The Red Room, were now 3-year-olds. They had to have their temperatures taken at the door and wear masks, but this did not phase them; we quickly resumed our classroom routines. The desire to be back in the classroom together was palpable, and the resilience of children and educators during this time was awe-inspiring. Though there were moments of hardship, it was also a year of profound learning. I learned salient lessons about being flexible, following children’s interests, and remaining curious about one another as vital community members.

To limit the exposure to COVID-19 at school, we were encouraged to spend as much time outdoors with the children as possible. Roosevelt Island Day Nursery is a small progressive school on Roosevelt Island, a picturesque island between New York City’s Upper East Side and Long Island City in Queens. It is a quiet oasis from the big city and a pleasure to walk around with its beautiful views of Manhattan on the East River. Even more exciting for children is that Roosevelt Island has nearly every type of vehicle! A red tram crosses the river parallel to the Queensboro Bridge; barges, tugboats, and ferries use the river daily. Even a quaint little red bus travels around the island free of charge. When teachers were encouraged to spend more time outdoors, we were happy to oblige.

Often, the children were silent and completely mesmerized as they watched these large machines lift stones and move them toward the river.

Elizabeth Troisi

We took walks throughout Roosevelt Island every day. Some days, we would stop to look at the boats in the river, and a few curious children would contemplate the existence of mermaids as they watched the waves hit the rocks. Soon, we continued our walks further down and into Southpoint Park, which was undergoing construction. There were many large construction trucks and machines hauling dirt and rocks. This bustling construction site caught our attention, and Southpoint Park became a new destination for our walks. Teachers allowed children to sit on the grass or rock ledge to watch the construction vehicles work. Often, the children were silent and completely mesmerized as they watched these large machines lift stones and move them toward the river. We continued to visit the construction site, following their enthusiasm.

After several weeks of visits, the children became particularly interested in a construction vehicle with a large shovel on the front.

This truck was in the back of the park, and we often ended our observations here. After a couple of weeks, the worker operating the truck began to notice us. He would lift the shovel up and down for the children and wave to us. Remember, this was still 2020; everyone wore facemasks, covid vaccines were unavailable, and social distancing was still the norm. His willingness to connect with us, even in this simple way, impacted the children.

When we returned to school that day, a child asked, “Does he have a family?” The question about his family stayed with me. As we ate lunch together, it dawned on me that this could be part of the experiences I had only read about during my studies and was encouraged to explore by many professors in my graduate education program. As the education reformer John Dewey (1938) insightfully stated in his work Education & Experience, “[educators] should know how to utilize the surroundings, physical and social, that exist so as to extract from them all that they have to contribute to building up experiences that are worth while” (p. 40). I understood that this experience was worthwhile, and later that school day, children and teachers worked together to make an envelope using construction paper and tape. Inside the envelope, teachers wrote out all the questions the children had dictated for the “construction worker in the yellow truck with the large shovel on the front.” On the outside of the envelope, we taped a photo we had taken of the truck that day. Some children had questions, while others commented, “I love your truck.” Another child asked, “What’s your name?” as well as the one question that began this dialogue, “Do you have a family?” Teachers wrote about our school and added our classroom email so he could respond to us. We planned to find him and hand him the letter during our next walk.

The following day, to our surprise, we received an email from Joseph Monte, the man who operated our favorite truck! Joe wrote to us with great pride and accomplishment for his work.

On our walk the next day, we were disappointed that we could not find him or the truck. We handed our homemade envelope to a different worker, instructing them to please give our note to the person operating the truck pictured on the front. With a smile and chuckle, he agreed. The following day, to our surprise, we received an email from Joseph Monte, the man who operated our favorite truck! Joe wrote to us with great pride and accomplishment for his work. He introduced himself to us and kindly corrected our reference to him being a construction worker. In fact, Joe is an Operating Engineer for the Local 15 Union, and that truck with the large shovel in the front is called a front loader truck. He also told us about his family: he had a wife and two children in high school. Joe answered our questions with grace, openness, and an understanding of his audience — a group of curious 3-year-olds. The classroom was abuzz with excitement about making this connection with Joe! At the end of the letter, Joe told us that he was leaving Roosevelt Island to work at another job site and that his last day working at Southpoint Park would be Monday. He noted that it might rain that day, so he probably wouldn’t see us on our walk, and he signed it, “Your friend, Joe.”

On our walk the next day, we were disappointed that we could not find him or the truck. We handed our homemade envelope to a different worker, instructing them to please give our note to the person operating the truck pictured on the front. With a smile and chuckle, he agreed. The following day, to our surprise, we received an email from Joseph Monte, the man who operated our favorite truck! Joe wrote to us with great pride and accomplishment for his work. He introduced himself to us and kindly corrected our reference to him being a construction worker. In fact, Joe is an Operating Engineer for the Local 15 Union, and that truck with the large shovel in the front is called a front loader truck. He also told us about his family: he had a wife and two children in high school. Joe answered our questions with grace, openness, and an understanding of his audience — a group of curious 3-year-olds. The classroom was abuzz with excitement about making this connection with Joe! At the end of the letter, Joe told us that he was leaving Roosevelt Island to work at another job site and that his last day working at Southpoint Park would be Monday. He noted that it might rain that day, so he probably wouldn’t see us on our walk, and he signed it, “Your friend, Joe.”

Despite the rain, the teachers prioritized our walk on Monday. It was overcast, misty, and grey outside; however, we put on our coats and hats and took the trek to meet Joe. We were happy to immediately spot his front-loader trucker when we arrived at the park. He recognized us, and we greeted each other with big smiles and waves. Joe thanked us for reaching out to him and told us how excited he was to receive the letter from us. He said he had taped the photo up in his garage to see it every morning. It was heartwarming to hear that this experience was equally as important to him as it was to us. He told us that his next job at Coney Island would require some big drill tools and that he would love to keep in touch and send us photos and videos of his work. On our walk back to school, the children talked about Joe and eagerly anticipated what the big drills would look like. “Will they be loud?” one child asked.

Emergent curriculum and responsive teaching practices are instrumental in fostering meaningful learning experiences for children. These practices ensure that learning is not only developmentally appropriate but also reflective of children's interests and experiences.

Skilled educators design enriching learning opportunities that resonate deeply with children – drawing inspiration from children’s communities, their daily experiences, and the significant people in their lives. Through purposeful planning of these experiences, children not only engage actively in learning but also witness the representation of their identities and communities within their early learning environments.

Skilled educators design enriching learning opportunities that resonate deeply with children – drawing inspiration from children’s communities, their daily experiences, and the significant people in their lives. Through purposeful planning of these experiences, children not only engage actively in learning but also witness the representation of their identities and communities within their early learning environments.

The correspondence between The Red Room and Joe lasted until late spring of that year. He sent us numerous exciting videos of the machines he worked with, and he even showed us an old glass bottle and vase he found while using the drill to dig deep into the earth.

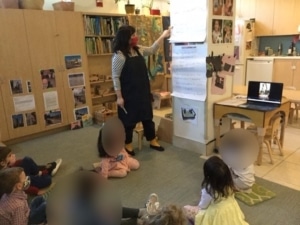

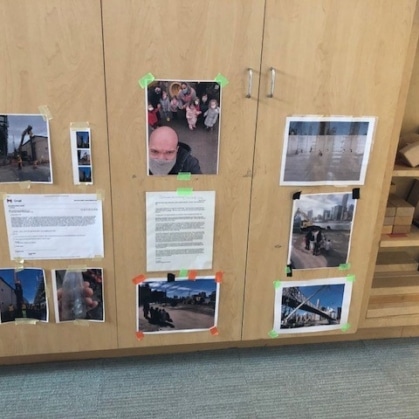

The children and teachers watched the videos and observed the images during group meetings. Then, the children would ask questions and comment, and teachers would dictate their words into written text on a large piece of paper. This process helped the children see their ideas and language in writing, encouraging literacy development. We would email Joe the questions and comments, and he would respond. Meeting times were exciting as we gathered together to listen closely to hear what Joe had to share with us. Our classroom environment began to reflect our experience; teachers printed photos and documented the process throughout the classroom.

The children and teachers watched the videos and observed the images during group meetings. Then, the children would ask questions and comment, and teachers would dictate their words into written text on a large piece of paper. This process helped the children see their ideas and language in writing, encouraging literacy development. We would email Joe the questions and comments, and he would respond. Meeting times were exciting as we gathered together to listen closely to hear what Joe had to share with us. Our classroom environment began to reflect our experience; teachers printed photos and documented the process throughout the classroom.

The images sparked conversations about what we were learning from Joe during Free Play and other parts of our daily routines. The children’s block structures became more intricate, frequently reflecting the machines and construction sites that Joe shared with us. Conversation skills and language were developing because of this child-led interest; even as children had to quarantine if they got sick, families would share with teachers that children would ask to take walks to Southpoint Park because their interest was so strong.

Undoubtedly, the COVID-19 pandemic caused educators to reevaluate their teaching practices. For me, it provided a moment of reflection that brought me back to my roots and reconnected me to my passion for teaching.

I recently spoke with Joe to tell him that I was writing this article. In the email, Joe expressed how happy he was to be a part of this experience. He wrote:

“The feeling is mutual with the lasting impression you and your class have left with me. Doing my little part with your class gave me a very small and short glimpse into what it is like being a teacher/role model for young children. You truly have a very important job, and I’m glad we have teachers like you that take it as seriously as it should be.” (J. Monte, personal communication, February 3, 2023)

Joe also expressed that he would love to share his work with my current class of children. A tangible sense of community and purpose still came from this experience, even though it was several years ago. Salvatore Vascellaro powerfully writes about the importance of experiences like this, calling them a “force” and “a vision of a more just society and the individual’s role in creating that society” in his book Out of the Classroom and into the World (2011, p196). I hope to inspire educators to be models for their students, even the youngest ones, by viewing the people around us as a part of a community with unique experiences and information to share.

I encourage educators to take walks outside and talk to the children about what they see. If you teach at a school where outdoor walks are not an option, take a walk around your school building; who helps keep the school clean? Who takes care of the grass or trees outside of your school building? When met with kindness and curiosity, you will be surprised at how eager people are to share parts of their lives and experiences. This is a wonderful learning experience about what grown-ups do each day and shows children how we work together to make a community.

References

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Educations. Simon & Schuster.

Vascellaro, S. (2011). Out of the Classroom and into the World: Learning from Field Trips, Educating from Experience and Unlocking the Potential of Our Students and Teachers. The New Press.

Our Critical Competencies program helps transform everyday teacher-child interactions into meaningful learning moments.

Next Up

Go to Next Resource

distillation

Buzzwords Explained: Play-Based LearningPlayful exploration is a natural way of learning. Explore how caregivers and professionals can encourage and promote play-based learning.