Our State of Babies Yearbook shows where each state stands in supporting babies and toddlers.

Home/Resources/Early Development/What’s the most compelling data in the early childhood field you’ve seen lately?

What’s the most compelling data in the early childhood field you’ve seen lately?

From early intervention, to home visiting, to sensory processing — early childhood professionals weigh in on what's been on their minds.

Author

Heidi Hagenson, MA-ECSE

Senior Training and Technical Assistance Specialist National Center on Early Childhood Development, Teaching, and Learning (DTL)

Heidi has worked with diverse populations in the early childhood field throughout the last 15 years and have served in varied positions and settings including public, private and Head Start programs. She currently serves as a Senior Training & Technical Assistance Specialist with NCECDTL where she provides focused training and technical assistance to Office of Head Start Regional Office staff on topics related school readiness. She believes through passionate service, innovative thinking, collective ingenuity and collaboration we can empower people to change the world - one child, family and community at a time.

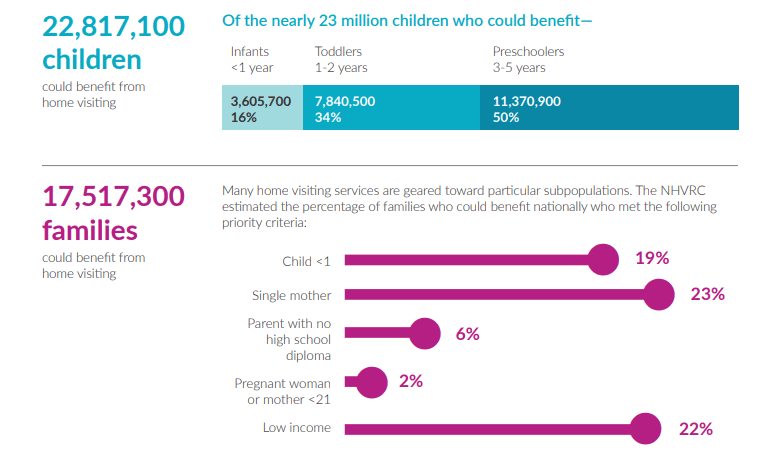

I was shocked when I read that home-based service providers are reaching less than 2% of children nationwide who could benefit from home visiting.

Heidi Hagenson

We know that home-based programs are a two-generation model that provides support for the whole child and family well-being through comprehensive services. Early Head Start (EHS) in particular serves as a buffer to prevent and address a variety of outcomes associated with families who are from the most at-risk backgrounds and living in poverty.

According to the Yearbook, of the 280,000 children who received services, 58,736 of those children were also enrolled in EHS home-based services. So, what does this mean for us? How can we empower families to be rooted in the knowledge that they are their child’s first and best teacher? How can home visitors and families partner effectively to support their immediate needs while fostering dreams for the future? How can we increase the number of families we reach through home-based services? Where do we go from here?

We can explore, nurture, and grow home visitors’ ability in honoring the culture and diversity of each family while partnering with them to support their child’s development. We can support home visitors in examining their own perceptions and unconscious bias and how that can affect support offered to families. We can lay the foundation for building trust, valuing family identities, and understanding the importance of reciprocity of information between home visitors and families. We can leverage the strong relationships between home visitors and existing families to recruit and reach new families who could benefit from home-based services.

Author

Elizabeth Frenette

Senior Policy Analyst, ZERO TO THREE

Elizabeth leads HealthySteps sustainability efforts in New York by working with heath systems, key stakeholders, payers, and policymakers to secure long-term funding for service delivery to children and their families. She serves as a subject matter expert on HealthySteps growth and scale and supports the HealthySteps network through direct technical assistance with billing and coding for Healthy Steps-related services.

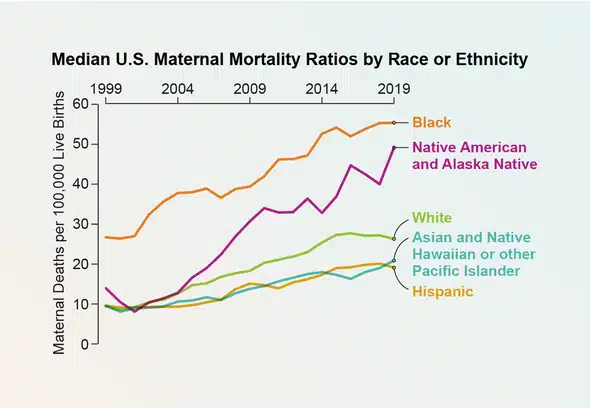

I just read a newly published study in JAMA about the staggering upward trends of maternal mortality by racial and ethnic groups in the U.S. This study used vital registration and U.S. census data from 1999 to 2019 and included pregnant or recently pregnant people ages 10 to 54 years. The researchers found more maternal deaths per 100,000 live births (MMRs) in 2019 than 20 years ago for all racial and ethnic groups.

The researchers found particularly alarming disparities in maternal mortality for American Indian and Alaska Native and Black pregnant people. Observed median state MMRs increased from 14.0 to 49.2 among the American Indian and Alaska Native population and 26.7 to 55.4 among the Black population.

This trend is unacceptable for our pregnant people, babies, and their families. Early relationships are paramount to each child’s development.

Elizabeth Frenette

While prevention efforts during this study period appear to have had limited impact in addressing this crisis, there are important public health policy measures that have the potential to change this trajectory. Policies that increase the likelihood pregnant people will access comprehensive healthcare before, during and after pregnancy can help. Continuous Medicaid coverage for pregnant people through their child’s first year of life is one such example of important health policies. Expanding and diversifying the maternal healthcare workforce could also help to reduce racial and ethnic inequities and improve rates of preventable maternal mortality.

Author

Ann Isbell, PhD

Program Officer, First 5 LA

Ann’s work focuses on practice and systems change to create partnerships and networks of care to ensure the families with young children are able to access high-quality resources and services when they need them.

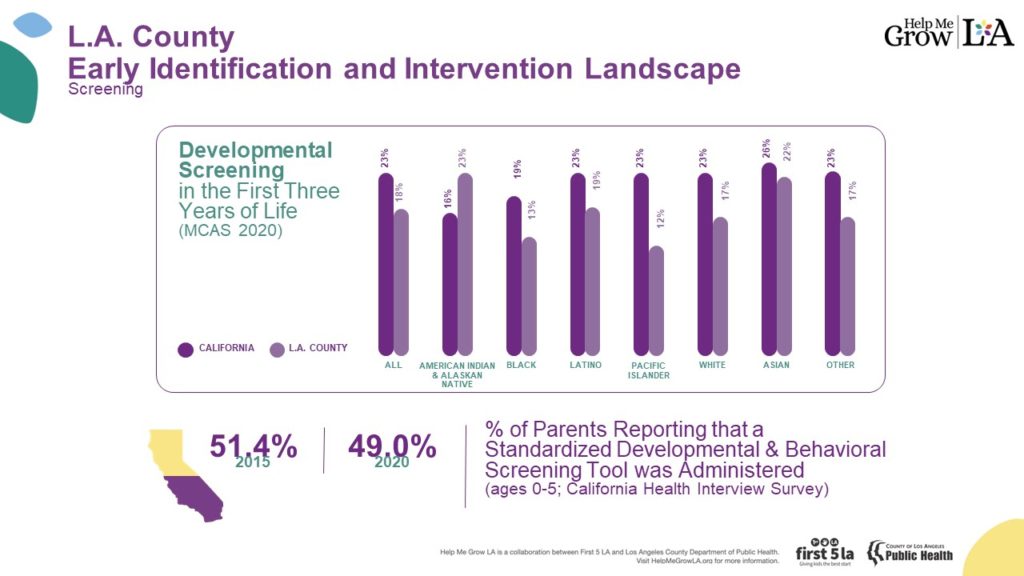

I have spent my career planning and evaluating early childhood initiatives and am currently focused on early identification and intervention (EII) for developmental delays. As part of this work, I lead a Data & Evaluation Workgroup of provider and parent representatives, and together we spend a lot of time looking at the imperfect data that exists on EII in Los Angeles County. The data helps us set baselines and benchmarks which we will ultimately hold ourselves and others accountable to.

One of the data sets we recently looked at is from the Managed Care Accountability Set (MCAS), collected annually from managed care health plans from throughout California. When we looked at this data we found that, in 2020, only 18% of infants and toddlers in L.A. County received a developmental screening in the first three years of life. Furthermore, when we disaggregate by race and ethnicity, the data shows disparities in screening, with certain populations having even lower screening rates.

Another data set about developmental delays told a different story, however. This data set, also from 2020, comes from the California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), which is the state’s largest annual Health-Related survey including more than 20,000 Californians. In this survey, which is self-reported, almost half of the parent respondents said their young child’s health provider administered a standardized development and behavioral screening (SDBS) tool. This means that likely half of California’s parents believed their child got screened.

Receiving intervention services when a delay is detected early can improve physical, mental and socioemotional health and overall well-being, and developmental screening is the first and best step to identifying children who could benefit from intervention services.

Ann Isbell

When I look at these two data sets, I am struck by two things. One, that the definition of developmental screening is not uniformly understood across parents and health care plans, resulting in the two widely different numbers, with the MCAS having a more defined criteria of what counts as a developmental screening. Secondly, and most importantly, however, is that, at best one in every two children and at worst one in every five is receiving this important intervention tool. This is simply not good enough.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children are screened using a validated tool at 9, 18 and 30 months. From these data, we know that we are far from meeting this recommendation.

The good news is we are working on it. At First 5 LA we are working with partners across the county to better understand this data landscape and identify goals and objectives and develop strategies and tactics to address the story the data tells us. This include partnering to bring the Help Me Grow model to Los Angeles and other partnerships including with a local health plan to improve developmental screening rates.

Author

Rebecca Berg, OTR/L, IMH-E

IECMH Occupational Therapist, Integrated Clinical Model Lead at Cooper House PLLC

Rebecca’s professional home is Cooper House, an infant mental health practice in Seattle, WA, where occupational therapists and mental health therapists work in close collaboration and transdisciplinary practice to serve children 0-5 and their families. Rebecca serves the team in the role of Integrated Clinical Model Lead, synthesizing theory into practice and furthering the development of this model. Her work is characterized by her deep curiosity about the experience of others and commitment to close partnership with caregivers to understand the many moving parts of development within the caregiver/child relationship, their family system, and the community in which they live.

Sensation is the brick and mortar of my work as an infant mental health occupational therapist. Sensation isn’t just something that that we react to, it’s the raw material from which we construct our understanding of the world: our sense of self, our relationships, the culture and environment into which we are born. It’s the stuff from which memories are made and agency emerges. But, meaning is not constructed in isolation. The flow of sensory experience is parsed and given shape in the context of our early interactions and relationships with others.

I’m excited by the growing transdisciplinary interest in the relationship between patterns of sensory processing (traditionally the domain of occupational therapists) and patterns of attachment adaptations (traditionally the domain of mental health therapists).

Rebecca Berg

For example, this research reviews existing literature to describe what we know about the correlation between sensory health and relational health. The authors call for further study and suggest that occupational therapists should consider both sensory processing and attachment patterns when planning their interventions.

But, this interconnection also holds the potential for all professionals to forge more inclusive pathways for attunement and healing for the families we serve. It compels us to look beyond Western norms and medical/deficit models of what relationships should look like to understand the unique sensory-affective experience of the dyad before us. It resists the siloing of mind, brain, and body into separate professional disciplines, suggesting instead that we become fluent in the unique language of the relationship, the grammar of reciprocity, rhythm, proximity, and touch.

The case formulation framework we’ve developed at Cooper House, “The Inside/Outside Story,” emerged to capture and synthesize complexity for our integrated service delivery model: to support clinicians as they work to combine perspectives from each discipline, to share professional knowledge with families and invite them as partners into the work.

Author

Alison Peak, LCSW, IMH-E®

Executive Director, Allied Behavioral Health Solutions

Alison has spent the majority of her career dedicated to two primary passions: integrated behavioral health services in primary care settings and Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health. Alison is privileged to be a member of ZERO TO THREE 2020-2022 Fellows and to work alongside state and national colleagues to further Infant and Early Childhood services and workforce development. Clinically, Alison is passionate about working with children who have histories of early trauma and their caregivers, Reflective Supervision, and utilizing RSC to build leadership capacity in systems.

I recently came across a statistic that reported the average career duration of physicians and pharmacists is between 25 and 28 years. Comparatively, the average career duration for those in supportive professions like social work and early childhood education is 8 years (Cortis et. al, 2021). Eight years! That is so much training, effort, and opportunities for our young children and families that is lost in burnout and turnover. That also doesn’t recognize the impact of secondary trauma on those who are leaving our field. I also read another study that specifically looked at the wellbeing of infant and early childhood mental health (IECMH) providers during COVID-19 that found Reflective Supervision was a mediating factor to COVID related stress and to professional support (Morelen et al, 2022).

To me, that all says if providers are to care for the caregivers that care for infants and young children, then there must be organizations prepared to care for those professionals.

Alison Peak

Jeree Pawl’s quote of “Do unto others as we would have others do unto others” extends beyond the relationship between providers and caregivers and their infants/young children. It also calls us to build organizations, systems, and leaders who embody the IECMH core principles of dyadic work, recognition of intergenerational and historical trauma, social justice, and reflective practice. The IECMH field has spent years and considerable efforts researching the relationship between infants and caregivers, between caregivers and providers, and developing models for training evidence-based practices. All of this has been invaluable to the field, but the IECMH field also needs to increase our focus and resources to support the organizational environments where our providers make their professional homes.

We often discuss the parallel process of the emotions that occur between a child and a caregiver are replicated between a caregiver and a provider, but I also believe they become replicated between the provider and supervisors and systems. The leadership of our community-based programs are often struggling to hold the perspectives of babies, staff, and systems demands. Reflective Leadership is required to adequately support our IECMH staff and to develop healthy supervisor-supervisee relationships and healthy organizations.

In Reflective Leadership we consider the two components of Reflection on Leadership and Reflection as Leadership (Peak, et al, 2022). Reflection on Leadership gives us a guide for the opportunities to embody reflection in organizational activities and organizational culture. These include critical reflection, public reflection, productive reflection, and organizing reflection (Vance & Reynolds, 2010. In real life those domains might look like a town hall at a organization or a staff feedback survey. They could also look like debriefing a major organizational decision or the launch of a new data collection system. They’re great at guiding us to intentionally build in moments in our workflow to engage in reflection, but they don’t really assist us in considering how we show us humans who are in positions of leadership. Reflection as Leadership provides us with a framework of six key characteristics that support our “way of being” as Leaders who embrace IECMH core principles. They include empathy, humility, striving for diversity, seeking equity, transparency, and community (Peak et al, 2022).

Next Up

Go to Next Resource

open-letter

Why I Chose a Career in Early ChildhoodEarly childhood education is critical for children’s growth. Impassioned educators can make all the difference for young minds.