Marva L. Lewis, Tulane University

Rhonda G. Norwood, Louisiana State University

Abstract

This article explores the identity development of young children of color growing up in transracial adoptive homes. The authors present the story of a 6-year-old child with a history of severe trauma and how this trauma shaped her understanding of race and identity. After her eighth foster placement, the child’s play and talk became increasingly self-deprecating of her black skin color, leading to concerns that the child had begun to equate her movement from her previous foster homes with the fact that she was Black. The article concludes with a discussion of the need for a relationship-focused, strengths-based, ecological systems approach to evaluate ethical issues of racial identity formation within a sequelae of childhood trauma and placement into a multicultural family.

In this era of widening global and cultural boundaries, there is an increasing number of adopted children who are of a different race, culture, or ethnicity than their adoptive parent(s) (Marr, 2017). The Multiethnic Placement Act (MEPA) of 1994 was the first federal law to address the issue of race in adoption. For agencies receiving federal funds, denying transracial adoptions solely based on race was prohibited. Agencies could, however, use race as one factor among others when placing children into foster or adoptive homes. The Inter-Ethnic Adoption Amendment in 1996 (GovTrack.us, 2019) then made it impermissible to employ race as a factor in placing children. Transracial adoption of children remains regulated by state laws, which vary from state to state. These laws address a broad range of legal topics in relation to adoption that help guide local policies, judicial practices, and formal casework recommendations for placement of young children of color into transracial adoptive placements. The permanency and concurrent policies and practices outlined in the Adoption and Safe Families Act in 1997 urged adoptive agencies, judges, and child welfare workers to recognize the urgent developmental needs of infants and young children for permanency and speedy placement into “forever homes.” (See review of issues related to legal decision timeline and transracial adoption in Marr, 2017).

Despite the developmental importance of these rulings, guidelines, and practices, little attention has been given to the ethical issues for this type of placement from the perspective of the child. These laws, practices, and policies do not address the emotional and identity perspectives of children. What are the emotional needs and developmental implications for identity development of young children of color growing up in transracial adoptive homes?

The following case study describes the collaboration between a White, infant mental health therapist and an African American consultant. The consultation was initiated due to the therapist’s ethical dilemma and concerns about a young African American girl, “K’atrice,” who experienced a series of neglectful and abusive caregiving relationships, which caused extreme emotional and behavioral dysregulation. Once she was placed in a stable, loving foster home with a White caregiver, K’atrice began to exhibit an extreme aversion to the color of her own skin. As the case progressed without much improvement in K’atrice’s acceptance of her racial features, the therapist began to worry about the ethics of a White therapist working with—and a White foster mother caring for—this particular child.

We use a trauma-informed framework to reflect on the emerging racial identity of this vulnerable girl. We also use Urie Bronfrenbrenner’s (1979) concept of the interacting layers of the ecological environment in which children develop to examine the social, developmental, and environmental contexts of K’atrice’s experiences. We end with a discussion of her journey to address the questions of her identity in the face of repeated trauma and within a transracial adoption and therapeutic setting: Who am I? Where do I belong?

The Ethics of Transracial Adoption

The ethics of transracial adoption have been hotly debated. In 1972, the National Association of Black Social Workers opposed transracial adoptions and advocated for the expansion of placement of African American children in same-race foster and adoptive placements (Marr, 2017). One position argues that transracial adoptive parents will not be able to socialize their children to be able to cope within a racist society as well as same-race adoptive parents. The sparse findings from research on this question have been mixed. Research has demonstrated that transracially adopted children more often live in predominantly White communities, which can lead to feelings of isolation and poorly developed racial identities (Lee, 2003). Conversely, other studies have shown that, as adults, transracial adoptees fare well in terms of their self-esteem and sense of identity (see Park & Green, 2000, for discussion).

Transracial Adoption and Identity Development

Across cultures, a normative, developmental process for young children is the formation of their ethnic and cultural identities. These processes include developing their personalities and social identities within the standards of their culturally unique developmental niches (Lewis, 2000). Children’s identities are nurtured within the contexts of their family and larger social groups based on any number of characteristics such as their nationality, gender or sexual orientation, and social class (Clark & Clark, 1971). Some children develop within a larger sociocultural context where trauma and race are dominant themes, for example, in the form of severe adverse childhood experiences (Felitti et al., 1998) and intergenerational legacies of historical trauma of their families and cultural groups (Lewis, McConnico, & Anderson, in press; Lewis, Noroña, McConnico, & Thomas, 2013). These struggles compound the process of developing their individual identities. The emotions associated with the historical trauma experiences of their group identity may be seared into their memories and neurobiology for a lifetime (Schechter & Rusconi Serpa, 2011).

Racial phenotype (the observable characteristics of an individual) readily distinguishes Black Americans from other racial groups. The societal legacy of being Black in America includes a traumatic history of discrimination, stereotypes, and racism based solely on the indelible, genetically determined feature of race—skin color. As a result, Black1 families must use psychologically protective child-rearing practices that serve to insulate children from the slings and arrows of everyday racism, discrimination, and prejudice based on their skin color (Lewis, 1999, 2016, 2019). Parents of color are also tasked with the responsibility of helping their children develop their identities within a racially divided society. Their shared racial features and experiences related to those features enable them to share a deeper level of racial empathy with their children. The parents’ lived experiences of varying degrees of discrimination and prejudice based on their skin color better provides the basis for racial socialization goals to prepare children to live in a racially stratified society.

Transracial adoptive parents have the same task of encouraging the healthy development of their children’s ethnic and cultural identities. However, they do not share the same physical characteristics and related experiences of their adopted children. Therefore, adoptive parents whose race differs from their children face additional challenges with nurturing healthy ethnic and cultural identities.

1 The term Black denotes a sociopolitical constructed racial group category. The term African American refers to the culture or ethnic identity of the group

K’atrice’s Story—by Rhonda Norwood

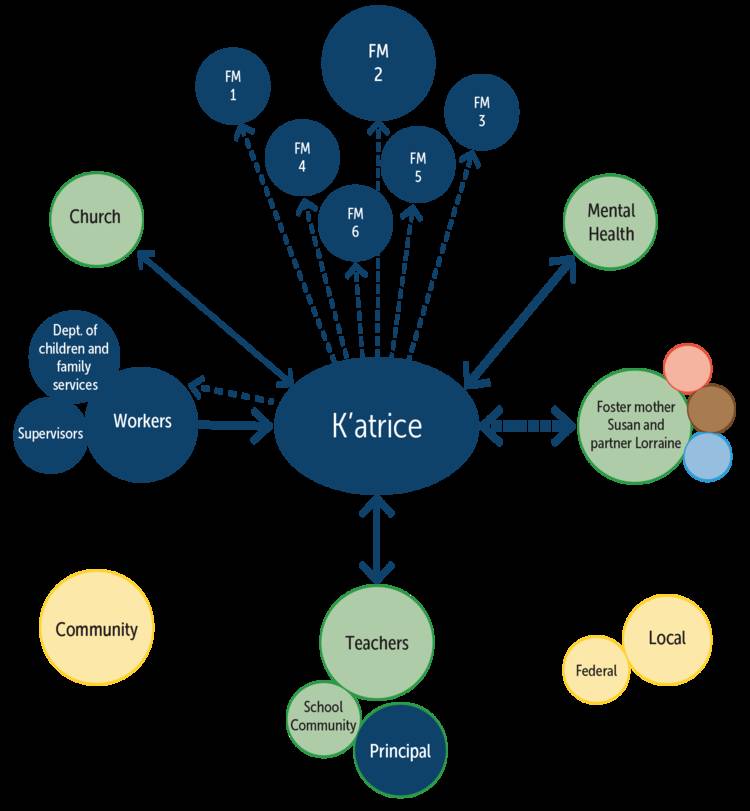

The following story explores issues related to trauma, race, and identity. K’atrice2 experienced severe trauma during her early years within the caregiving contexts of people whose skin color looked like hers. She was then placed into a loving environment with a White caregiver. The overlaying ecological framework in which K’atrice was embedded at the time of consultation is illustrated in Figure 1. K’atrice experienced a variety of positive and negative messages about race and skin color from many levels of her ecological niche of same-race and different-race relationships. My concerns included a worry about the capacity of the White adoptive family to racially socialize K’atrice in her journey of racial identity development.

2 All names and some identifying features have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Figure 1. K’atrice’s Ecological Framework

Background and Early Life

K’atrice was first referred to our clinic 2 months prior to her 6th birthday by her child protective services (CPS) worker, Danielle. This clinic provided services to young children from birth to 6 years old placed in foster care. The following history was compiled from multiple reports from the CPS worker, Danielle, and several of K’atrice’s former foster parents.

K’atrice, a petite, African-American girl, first entered foster care when she was 18-months-old. Her father was physically abusive to her mother, both parents were using a variety of drugs, and there were also reports of her mother having an unspecified mental illness. During one fight, which K’atrice and her 6-year-old brother witnessed, her pregnant mother was beaten so badly that she was rushed to the emergency room. The injuries were severe, and she delivered the baby at 33 weeks’ gestation. The baby, Nevaeh, also received multiple injuries while in-utero, including a traumatic brain injury. At this point, CPS placed K’atrice with a fictive-family member, her brother with the maternal grandmother, and Nevaeh in the certified, non-kin foster home of Blaire.

After living with the fictive-family member for approximately 1 month, CPS discovered that the caregiver was allowing K’atrice to stay with her biological parents unsupervised. Katrice was then placed with her sister Nevaeh in Blaire’s foster home, where she remained for 2½-years. She had inconsistent contact with her biological mother during this period, and she never saw her biological father, who was intermittently incarcerated. When K’atrice was 3 years old, Nevaeh died from complications from the prenatal injuries. Blaire grieved the baby’s death intensely, and she later reported to the therapist that this period was when “everything went downhill.” At that time, there were several foster children in Blaire’s home, and CPS began to have concerns about the children’s safety. K’atrice had been left unattended, wandered into traffic, was hit by a car, and sustained a broken leg, and Blaire and her husband were in the process of divorcing. Because of these and other concerns, CPS removed K’atrice from this home when she was 55-months-old. CPS reported that K’atrice was “bonded” to these caregivers prior to her removal.

Following this placement disruption, K’atrice spent the next year moving from home to home; the longest placement lasted 4 months, and all placements disrupted reportedly because of K’atrice’s behavior. Each of these homes were with single, African American foster mothers. At this point, K’atrice was displaying oppositional behaviors, threatening foster parents (e.g., “I’m going to tell Danielle that you hit me!”), smearing nasal mucus on herself and things, having tantrums that lasted for hours, and acting aggressively with other children in the homes. K’atrice often demanded to call her CPS worker to ask for a new home when she was upset. One of these foster mothers reported that when she informed K’atrice she would be sent to a new home, K’atrice responded, “Good!”

When K’atrice was 6 years old, she was placed in the home of a Caucasian foster mother, Susan. Approximately 3 weeks after placement, though, Susan had already decided that she, too, could no longer provide care for K’atrice. Susan had one biological son and another foster child who had special medical needs, so Susan was concerned that K’atrice’s aggression could jeopardize the placement of that child, whom she was hoping to adopt. It was during this period that CPS finally referred K’atrice for treatment.

CPS reported to the clinic that when they arrived to get K’atrice from Susan’s home to move her to another therapeutic foster home, she reacted very differently than when leaving the previous homes. K’atrice reportedly sobbed, screamed, and clung to Susan, and she had to eventually be pried away and restrained in the car during transport. The day after being placed in the new home, K’atrice was brought into the clinic by her 6th foster mother.

Evaluation

K’atrice first came to the clinic with Esther, a 62-year-old African American woman who had been a “therapeutic” foster mother for 16 years; Esther laughingly reported that she had fostered “too many children to count!” She was soft spoken and seemed like a gentle woman, but there were immediate concerns with some of her comments about K’atrice, and she did not intend to provide enduring care for her or participate in treatment with her. Concerns were immediately reported to CPS, who said they would try to find another placement for her.

Adoptive parents whose race differs from their children face additional challenges with nurturing healthy ethnic and cultural identities. Photo: DNF Style/shutterstock

Meeting K’atrice

During this same intake session with Esther, K’atrice presented as a petite, quiet, girl, who was very wary of the clinic and clinicians. It was difficult to imagine that this soft-spoken girl could wreak such havoc in a foster home. During this first encounter with K’atrice, I asked her if she knew why she had come to my office:

K’atrice: “I need to learn to be good so I can go back and live with Ms. Susan.”

Rhonda: “Did you like living with Ms. Susan?”

K’atrice: “Yes, and I want to go back.”

Rhonda: “I’m not sure that you can go back there, but Danielle [CPS worker] and I are going to work very hard to find you a wonderful home where you can stay forever.”

K’atrice: “If I were white, could I live with Ms. Susan?”

After recovering from hearing this heartbreaking question, I continued to talk with K’atrice about her experiences in Susan’s home, particularly regarding how it compared to her previous homes. K’atrice’s accounts of the insensitivity and, in some cases, abuse that occurred in those foster homes were very similar to CPS’s accounts. In stark contrast, she portrayed Susan as a loving caregiver, and she was desperate to be able to return to her home. We ended this first session, and I again tried to reassure her that the adults in her life were going to find a safe home for her. I informed CPS that we would begin individual therapy while waiting for Katrice to be moved to a permanent home, at which point she could receive attachment and trauma-informed treatment within the context of the caregiving relationship.

I received a phone call from CPS later that day informing me that, after leaving the clinic, Esther had been arrested for ejecting 6-year-old K’atrice and another foster child out of her car and leaving them alone on the side of the interstate for laughing too loudly on the ride home. When Susan heard about this incident a few days later, she immediately petitioned CPS to have K’atrice returned to her home. She committed to adopt K’atrice and attend dyadic/family therapy in order to help K’atrice overcome her traumatic experiences. CPS moved K’atrice to a temporary respite home (K’atrice’s 7th placement), as they were skeptical about moving K’atrice back to Susan’s home given the prior request to have K’atrice leave.

Treatment

Once K’atrice was moved back to Susan’s home, I began to work closely with Susan on helping K’atrice develop better self-regulatory capacities. Despite some areas of rigidity that are often typical of many Southern parents (e.g., well-behaved children say “Yes, ma’am!”), Susan was generally empathic and understanding that K’atrice’s behaviors were symptoms of her traumatic experiences, and she was motivated to learn how to help K’atrice recover. Treatment included elements of childparent psychotherapy (Lieberman & Van Horn, 2004), individual work with Susan, and individual therapy with K’atrice using a trauma-informed protocol for young children (Scheeringa, Weems, Cohen, Amaya-Jackson, & Guthrie, 2011). The goal of treatment was to foster emotional attunement between Susan and K’atrice, increase Susan’s sensitive and consistent responses to K’atrice’s needs, and improve K’atrice’s emotional and behavioral dysregulation.

Now that she was in a stable, safe environment, K’atrice’s needs initially did not seem that different from most of the other foster children on my caseload. Very quickly, however, K’atrice began to demonstrate themes in her play and discussions that made me, as a White therapist, very uncomfortable. Following is an excerpt from one therapy session after K’atrice chose a dollhouse for play:

K’atrice: “All my people are white.” (She selected one black doll and several white dolls.)

Dr. Norwood: “What about this one?” (pointing to the black doll)

K’atrice: “She comes from another family but lives with the white people.”

Dr. Norwood: “Oh, I see. She doesn’t live with the other (black) family?”

K’atrice: “No, she found the perfect family.”

Each week, K’atrice introduced similar racially related themes into her play. At the beginning of another dyadic session, I quietly handed Susan a black doll to cradle and nurture while K’atrice was choosing her toys; when Katrice turned around and saw that Susan was holding the doll, she took it from her and said, “You can’t have that one, it’s ugly!” After slamming the doll to the ground, K’atrice replaced Susan’s doll with a white one.

Through identity formation, an individual child “belongs”—first to a family, then to an extended family, then to a community or neighborhood, and, finally, to a society. Photo: Expensive/shutterstock

Another prevalent theme in K’atrice’s play and talk revolved around “heaven.” This theme appeared to be directly related to Nevaeh’s death, as K’atrice often talked about one day seeing her sister again in heaven. During another dyadic session, K’atrice and Susan were talking about some difficult behaviors she had during the week, and K’atrice put her head down and quietly said, “When I go to heaven, I’ll be white.”

I had never worked with a child so young who had such pervasive concerns about the color of her skin. Susan also voiced concerns that K’atrice was making derogatory statements about her skin color at home. Hypothesizing that needing to maintain proximity to a White foster mother was the root of these negative perceptions, I suggested various interventions for Susan to try at home; K’atrice soon began saying things like, “My mommy likes my skin, and so do I.” However, nothing seemed to assuage K’atrice’s conviction, during her play and in spontaneous conversations, that white skin was more desirable than hers.

Furthermore, this conviction appeared to generalize into other problems for K’atrice and Susan. For example, when Susan disciplined K’atrice, K’atrice began to say that she was always being singled out among the three children in the home. (Although this statement could have been accurate, there was never any evidence of Susan doing so, and Susan’s observed interactions with K’atrice were always reasonably sensitive and appropriate. However, K’atrice had significantly more behavioral outbursts than the other children, which probably did result in more discipline.) Over the next year of work together, “fairness” and being different (and treated differently) became themes that generalized to the school and other family members, and in many different contexts.

Within a few months after K’atrice arrived, CPS placed another child into Susan’s home, 6-month-old Jaliyah. Jaliyah was an African American girl who had sustained brain damage after being shaken by her biological mother. Susan was hopeful that having another Black child in the home would help K’atrice to feel more secure in their diverse family, and it seemed, initially, that K’atrice was very happy with Jaliyah’s arrival. The improvements, however, were short lasting, and the emotional dysregulation specifically regarding her skin color continued to worsen, even as the general behavioral and emotional dysregulation improved.

As we developed and addressed her trauma narrative in therapy (Scheeringa et al., 2011) over those first few months, I began to wonder if K’atrice was associating black skin with her traumatic experiences (see Table 1). All her previous foster homes, which were difficult and sometimes abusive placements, had been with African American foster parents, and her African American CPS social worker was the one who brought her to all those different homes. If K’atrice had indeed begun to classify people as being good and bad, or safe and unsafe, based on their skin color, then a very important question for me became clear: Can a white therapist and a white foster mother help such a child disentangle her traumatic experiences from her developing racial identity? Or, would these safe, supportive, White people exacerbate the rejection of her black skin? It was at this point that I contacted Dr. Lewis for advice.

2 All names and some identifying features have been changed to protect confidentiality.

Consultation—by Marva Lewis

The consultation process involved developing an understanding of the unique factors that characterized K’atrice’s significant relationships and family dynamics, as well as the larger environmental and societal forces at play.

Theoretical Frameworks

Cultural identity and ethnic identity are created through healthy connection with others who share similar traditions, values, and history (Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990). Ultimately, social acceptance and connection with primary caregivers and peers lead to feelings of individual and social power in children (Rohner, 1975). From child care through secondary education, there are individual relationships and relationships with groups that impact the developmental experiences of the growing child. Through identity formation, an individual child “belongs”—first to a family, then to an extended family, then to a community or neighborhood, and, finally, to a society. Haviland and Kahlbaugh (1993) proposed, “In our affective approach to identity, emotion is the ‘glue’ of identity that creates chunks of experience through processes of emotional magnification and resonance” (p. 328). This rule helps the individual discriminate which of a hierarchical set of experiences will have emotions attached to them. Dr. Norwood’s concerns centered on the potential implications of the emotional attachment and supportive relationships of a White foster mother and White therapist unwittingly and negatively influencing this young Black child’s positive racial identity development.

Several theoretical frameworks informed my consultation with this family and Dr. Norwood. Urie Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological systems theory explains that the relationships in K’atrice’s developmental niche, which came from larger social systems in her community that include the department of social services, the educational system, and the mental health system, influenced the development of her identity. An understanding was needed of the environmental messages about race that K’atrice received from individuals at these various systems levels. The impact of trauma on her identity formation as a normal developmental psychosocial crisis (Erikson, 1968) as well as her racial identify formation (Cross, 1991), was also considered throughout the consultation (Lewis & Ghosh-Ippen, 2004). Finally, attachment theory and a relationship-based assessment framework (Zeanah et al., 1997) also guided the process of assessment (see Box 1).

Table 1. Race of Caregivers and K’atrice’s Experiences of Childhood Trauma

| K’atrice’s Age | Type of Confirmed Trauma | Race of Caregiver/Attachment Figure |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 18 months |

Abuse (physical, emotional, and neglect, confirmed; sexual suspected)

Domestic violence Parental substance use Parental mental illness Parental separation Parental incarceration Separation from caregivers |

Black, biological parents |

| 18 months to 19 months | Neglect | Foster Home #1

Black, female caregiver |

| 19 months to 55 months | Neglect

Emotional abuse Physical abuse Separation of caregivers Hit by car Death of biological sister |

Foster Home #2

Black, male and female caregivers (Divorced near |

| 55 months to 63 months | Changed placements 4 more times

Emotional abuse Physical abuse |

Foster Homes 3, 4, & 5

All black, single foster mothers |

| 64 months | Abandoned on the side of the road after laughing in car; child was hypervigilant around foster mother prior to this | Foster Home #6

Black, single foster mother |

| 65 months | Respite home | 7th placement, unknown race |

| 66 months | None known | 8th placement, white foster mother and partner |

Three Levels of Relationship Assessment

The relationship-based tools that best fit this multilevel conceptual framework to address these questions included individual interviews with the therapist and the parents, the creation of an Eco-map (Hartman, 1978) to depict the quality of the relationships, a timeline of trauma and race of the associated caregiver, a projective measure using a version of the House-Tree-Person Draw drawing procedure (Buck, Warren, Wenk, & Jolles, 1999), and naturalistic observation of the entire family interactions during the ritual and routine of mealtime in the home (Miron, Lewis, & Zeanah, 2009; Wolin & Bennett, 1984). Multiple interviews with Dr. Norwood were also conducted, and the commitment, concern, and worry of this therapist to “do no harm” was clearly evident.

Interview With the Parent Subsystem

At the time of K’atrice’s adoption, which occurred shortly before the consultation, only one partner in a same-sex couple was able to adopt the child. Susan’s partner, Lorraine, however, was very involved with K’atrice’s treatment and daily caregiving. The initial interview with both Susan and Lorraine primarily focused on their perception of K’atrice. They openly shared their history as parents, as a marginalized lesbian couple, and their intentional plans for an adoptive family. They discussed their worries about their relationships with K’atrice. By the conclusion of the interview, it was clear that their worry centered on a fear of inadvertently negatively influencing K’atrice’s self-concept as an African American and her racial identity. Both parents were educated and had taken some courses on cultural sensitivity and awareness training in their professional lives. They described the steps and activities they had taken to communicate pride in African American heritage. They noted that their community, church affiliations, and extended family were White. The school K’atrice attended was also predominantly White. It was also clear that the acceptance of K’atrice by some of their extended family was somewhat reserved. I applauded the parents for their concerns and commitment to support K’atrice and all their children of diverse races. We made plans for an in-home visit to meet all the children and not single out K’atrice as the focus of the assessment. The in-home observations included the developmentally appropriate projective assessment measures including family drawings.

Recommendations

This family presented with a range of differences in terms of the characteristics of social identity: a racially White, lesbian couple, three of the children differed in gender and race and physical ability, adoption, and divorced parents. Although Jaliyah and K’atrice shared the same foster care status and skin color, Jaliyah’s severe cerebral palsy and tracheostomy tube made them look quite different physically.

The central issues in this family that were deemed most relevant to the core concern of the therapist—K’atrice’s concept of her racial self—seemed to center on how the parents value difference. Each member of this household is easily identified as belonging to different phenotypical groups. Dichotomous differences included gender (girl/boy), physical abilities (physically able/disabled), weight and size (large/small), skin color (dark/white), hair color (dark/blonde) and texture (very curly/straight), and roles and relationships (brother/sister; adopted child/biological child). These clearly visible dichotomies of differences that contrast with the parents’ very loving message to the children that they are all the same may have, unwittingly, created cognitive dissonance based on the perceptions of the children. Their eyes see visible differences. Social messages from their larger ecological environment teach the children (e.g., “She is different than me. I am a boy; she is a girl.”). Yet, as this richly diverse family tried to explicitly convey a message of equality among the children, the implicit message may have been that their differences were not important. In other words, perhaps the children were hearing, “I don’t see you as a unique individual. You are just the same as all the rest of the children.”

The recommendations to the therapist therefore fell into three categories: addressing the dynamics of the therapist relationship and racial identity of K’atrice, strengthening K’atrice’s attachment relationships with her adoptive parents, and increasing K’atrice’s connections with groups in the African American community.

The parents were advised to encourage all the children to come up with ideas about things that are different. The goal was to provide the children with developmentally appropriate schemas and templates to be able to talk about difference and emotionally experience acceptance for the differences they were born with and had no control in creating or maintaining. Not until children are adolescents will they be expected to begin the process of identifying with specific groups and individuating away from their family (Erikson, 1968; Spencer & Markstrom-Adams, 1990).

The parents were also encouraged to provide all the children with everyday tools to respond to and celebrate differences, reward acceptance of differences and cooperation, and discourage competition with one another. This goal can often be accomplished by using popular children’s stories, carefully selected characters in social media or television, and bedtime stories to practice recognizing emotions and to teach children how to use words to express all emotions.

Box 1. Relationship-Based Questions Used to Guide the Assessment

The assessment was guided by the following questions:

1. How well does this child fit into a family of children who are “different” in terms of race, gender, and physical abilities, and by same-sex parents who are viewed as “different” based on their sexual orientation?

2. What is K’atrice’s perception of herself as a member of this family created from a variety of identity groups?

3. How well can this family system prepare this child for predictable developmental challenges that lie ahead related to identity?

Relationships

The relationship between the therapist and child had been one of continuity and security. However, the reality was that the therapeutic clinical relationship would end; in fact, K’atrice had already “aged out” of the clinic’s services, but Dr. Norwood extended her treatment time frame given the severity of K’atrice’s symptoms. To aid K’atrice’s ability to develop positive relationships with other adults in the larger community, several suggestions were made. As a mechanism of transition from the frequency of therapy, the suggestion was made to have the parents enroll K’atrice in the local Big Brother/Big Sister program. Assignment to an African American Big Sister would provide K’atrice with a healthier relationship with an adult who looked like her and would allow her to build a positive relationship without the threat of trauma associated with prior caregivers. This Big Sister would be able to be with her for years and, regardless of her placement status, continue throughout K’atrice’s development as a teenager. A Big Sister could be one of the few relationships K’atrice would have that might bridge the many developmental transitions she will be going through as she reaches adulthood. This relationship could also ease the process of termination in the therapist–client relationship.

The other community-based activity that would offer K’atrice the opportunity to interact with African American girls who looked like her might be participation in a local chapter of the national organization of the Girl Scouts. Again, this organization may be a less emotionally threatening group activity during which she could earn badges, be a leader, and be the very smart girl that she was without the anxiety that accompanied close relationships. The family was advised to find a troop with a racially diverse membership. These types of relationships also do not have a social stigma attached to the relationships as is often the case with mental health services.

Discussion and Conclusions

K’atrice’s experiences of trauma and her journey through the process of developing her racial identity highlight the complexity of growth and development for children with diverse needs. Racial phenotype and dark skin color remain a consistent worry for young children growing up in an increasingly multicultural world. Childhood experiences of racial acceptance and rejection by significant attachment figures become intertwined with memories of the quality of their emotional relationships (Lewis et al., 2013). Consequently, these emotionally charged memories may be an unrecognized adverse childhood experience for some children. For K’atrice, this rejection was coupled with severe and chronic maltreatment by people who were Black—caregivers with the same skin color—resulting in her own skin color becoming a traumatic trigger and part of her internal working model (Bowlby, 1982) of these relationships. In the larger context of families, neighborhoods, and social groups, the caregiver’s and social message in response to a child’s skin color and trauma is an unrecognized area of vulnerability for children.

It is likely that K’atrice will continue to face many developmental challenges resulting from this internal struggle with her racial identity. Like K’atrice, many children struggle to regulate their emotions within challenging sociocultural and political contexts that they had no role in creating (Steele, 2004). As an early childhood clinician and a consultant, we worried that the impact of these complex racial factors often is lost in the pragmatic realities of achieving mandated permanency goals of adoption. We believe that for a clinician to ethically and holistically address the socioemotional needs of children, racial factors, despite their complexity, require attention as sources of trauma (Lewis & Ghosh-Ippen, 2004). Further, we believe that racial trauma must be approached from a relationshipbased framework and relationship-grounded tools and interventions. This therapeutic need may be more important with transracial adoptions.

Yet, superficial efforts to address race must not become a superficial “quick fix” nor remedy for a child’s or family’s substantive mental health needs. Race must not become the scapegoat for other trauma the child experiences such as bullying or simple rejection based on any number of other characteristics. The topic of race must be directly addressed and authentically and thoughtfully included in any treatment plan for the most effective and ethical service delivery to young traumatized children.

In the increasingly multicultural world of the future, there will be continued need for culturally informed professionals to guide parents—biological, foster, or adoptive—in their role of caregiver to their same-race, different- race, or multicultural children. We recommend parents and caregivers be supported to proudly draw on the strengths of their distinct cultural practices to build a strong attachment relationship with their child. As children in the future acculturate to new communities, we hope they will not feel the pressure to hide their authentic, ethnic selves to avoid the cruelty of stereotypes about their group. We pray they are not harmed by the implicit biases that may drive the behaviors of well-meaning caregivers. We remain steadfast in our belief and optimism for future multicultural communities that preserve and honor our cultural pasts and make room for creating an exciting and inclusive future.

Learn More

Young Children and Trauma: Intervention and Treatment C. Gosh-Ippen & M. Lewis (2006) In J. D. Osofsky & K. Pruett (Eds.). Rainbows of Tears, Souls Full of Hope: Cultural Issues Related to Young Children and Trauma (pp. 11–45) New York, NY: Guilford Press

The Skin Color Paradox and the American Racial Order J. L. Hochschild & V. Weaver (2007) Social Forces, 86(2), pp. 1–28

Trauma Reverberates: Psychosocial Evaluation of the Caregiving Environment of Young Children Exposed to Violence and Traumatic Loss M. L. Lewis (1996) In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Island of Safety: Assessing and Treating Young Victims of Violence, April-May, 16(5), (pp. 21–28). Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE, National Center for Clinical Infant Studies.

Violent Cities, Violent Streets: Children Draw Their Neighborhoods M. L. Lewis & J. D. Osofsky (1997) In J. D. Osofsky, (Ed.), Children in a violent society (pp. 277–298). New York, NY: Guilford Press

Working With Immigrant Latin-American Families Exposed to Trauma Using Child–Parent Psychotherapy C. R. Noroña (Fall 2011) The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: Spotlight on Culture

Multiple Social Identities and Stereotype Threat: Imbalance, Accessibility, and Working Memory R. J. Rydell, A. R. McConnell, & S. L. Beilock (2009) Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 949–966. DOI 10.1037/a0014846.

Media

Kids on Race: The Hidden Picture—A Look at Race Relations Through a Child’s Eyes CNN study that replicated the classic Doll study by Dr. Kenneth Clark demonstrating racial bias for white dolls and rejection of black dolls by both African American and White young children. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPVNJgfDwpw

Dark Girls Producer Bill Dukes Adult African American women recount their experiences of acceptance and rejection based on their dark skin color. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jJSTT6H8gUA

Frontline: A Class Divided Describes Iowa 3rd grade teacher Jane Elliott’s experiment, “Brown Eyes Blue Eyes,” to teach children the experience of discrimination. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1mcCLm_LwpE

About the Authors

Marva L. Lewis, PhD, is an associate professor in the Tulane University School of Social Work with a clinical appointment in the Tulane Department of Child Psychiatry. She is a former social worker in child protective services, trained in family therapy with the Colorado Institute for Marriage and Family therapy, and worked as a psychotherapist with the Colorado Infant Team and Tulane University Infant Team. Her research and publications focus on sociocultural influences on parent– child attachment relationships and the acceptance or rejection of infants and young children based on skin color and hair type.

Rhonda G. Norwood, PhD, LCSW, BACS, is an assistant professor of practice at the Louisiana State University School of Social Work. She earned her doctorate in social work at Louisiana State University. Dr. Norwood has 17 years of clinical and supervisory experience in a variety of agency settings and private practice. Her area of expertise is infant mental health, which includes working with young children and their families and perinatal mood disorders. Dr. Norwood’s area of research interest includes integrating effective interventions with child welfare services, parental representations of their children, and children’s narratives as representations of their relationships and worlds.

References

Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment. Basic Books. New York, NY.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Buck, J. N., Warren, W. L., Wenck, S., & Jolles, I. (1992). House-tree-person projective drawing technique. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Clark, K. B., & Clark, M. K. (1971). The development of consciousness of self and emergence of racial identification in Negro preschool children. In R. Wilcox (Ed.), The psychological consequences of being a Black American: A sourcebook of research by Black psychologists (pp. 323–331). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Cross, W. (1991). Shades of Black: Diversity in African-American identity. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. Retrieved from

GovTrack.us. (2019). H.R. 4181 — 103rd Congress: Multiethnic Placement Act of 1994. Retrieved from source link

H.R. 867—105th Congress. (1997). Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997. Retrieved from source link

Hartman, A. (1978), Diagrammatic assessment of family relationships. Social Casework, 59(8), 465–476.

Haviland, J. M., & Kahlbaugh, P. (1993). Emotion and identity. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (pp. 327–339). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lee, R. M. (2003). The transracial adoption paradox: History, research, and counseling implications of cultural socialization. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 711–744. DOI: 10.1177/0011000003258087

Lewis, M. L. (1999). The hair-combing task: A new paradigm for research on African-American mother-child interaction. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69, 504–514.

Lewis, M. L. (2000). The cultural context of infant mental health: The developmental niche of infant-caregiver relationships. In C. H. Zeanah (Ed.) Handbook of infant mental health, (2nd ed., pp. 91–107). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lewis, M. L. (2016, September 2). For African-American families, a daily task to combat negative stereotypes about hair. Retrieved from source link

Lewis, M. L. (2019). The intergenerational transmission of protective parenting responses to historical trauma. In H. E. Fitzgerald, D. Johnson, D. Qin, F. Villarruel, & J. Norder (Eds.), The handbook of children and prejudice: Integrating research practice and policy (pp. 43–61). New York, NY: Springer. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12228-7

Lewis, M. L., & Ghosh-Ippen, C. (2004). Rainbows of tears, souls full of hope: Cultural issues related to young children and trauma. In J. D. Osofsky, (Ed.) Young children and trauma: What do we know and what do we need to know? (pp. 11-46). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lewis, M. L., McConnico, N., & Anderson, R. (in press). Making meaning from trauma and violence: The influence of culture and traditional beliefs and historical trauma. In J. D. Osofsky, B. M. Groves, Violence and trauma in the lives of children. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Publishers.

Lewis, M. L., Noroña, C. R., McConnico, N., & Thomas, K., (2013). Colorism, a legacy of historical trauma in parent-child relationships: Clinical, research, & personal perspectives. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 34(2), 11–23.

Lieberman, A. F., & Van Horn, P. (2004). Assessment and treatment of young children exposed to traumatic events. In J. D. Osofsky (Ed.), Young children and trauma: Intervention and treatment (pp. 111–138). New York, NY, US: Guilford Press.

Marr, E. (2017) U. S. transracial adoption trends in the 21st century. Adoption Quarterly, 20(3), 222–231.

Miron, D., Lewis, M. L., & Zeanah, C.D. (2009). Observational methods in clinical practice and research in early childhood. In C. Zeanah (Ed.) The handbook of infant mental health (3rd ed, pp. 252–265). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Park, S. M., & Green, C. E. (2000). Is transracial adoption in the best interests of ethnic minority children? Questions concerning legal and scientific interpretations of a child’s best interests. Adoption Quarterly, 3(4), 5–34.

Removal of Barriers to Interethnic Adoption (Interethnic Adoptions Provisions), P.L. 104-182, 42 U.S.C. 471a.(3).

Rohner, R. P. (1975). They love me, they love me not: A worldwide study of the effects of parental acceptance and rejection. New Haven, CT: HRAF Press.

Schechter, D., & Rusconi Serpa, S. (2011). Applying clinically-relevant developmental neuroscience towards interventions that better target intergenerational transmission of violent trauma. The Signal: Newsletter of the World Association of Infant Mental Health, 19(3), 9–16.

Scheeringa, M. S., Weems, C. F., Cohen, J. A., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Guthrie, D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 853–860.

Spencer, M. B., & Markstrom-Adams, C. (1990). Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development, 61(2), 290–310.

Steele. C. M. (2004). Kenneth B. Clark’s context and mine: Toward a contextbased theory of social identity threat. In G. Philogène (Ed.), Racial identity in context: The legacy of Kenneth B. Cark. Decade of behavior (pp. 61–76). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Wolin, S. J., & Bennett, L. A. (1984). Family rituals. Family Process, 23(3), 401–420. doi:org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00401.x

Zeanah, C. H., Boris, N., Heller, S. S., Hinshaw, S., Larrieu, J. Lewis, M. L.,… Valliere, J. (1997). Relationship assessment in infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 18(2), 182–197.