Sarah Haskell and Heidi Pace, Infant Toddler Specialist Ltd., Greymouth, New Zealand

Abstract

Infant and toddler specialists working in Aotearoa (New Zealand) face an ethically complex question when the government requests an assessment of children from indigenous Māori culture. In this article, the authors explore the question: “Is it ethical to undertake parenting assessments and act as expert witnesses in cases which may result in the infant/child being removed from the parent, especially given the history of forced removal of Māori children from their families during colonization?” The authors describe their investigation of the history of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), the principles put forth in the body of the treaty, the legislation that grew out of the advocacy for the principles of the treaty, and how well those principles and laws are honored by the governmental agencies, such as Oranga Tamariki and the Family Court, and the implications for the assessment process. The authors also discuss the role of reflective supervision in ethical decision-making.

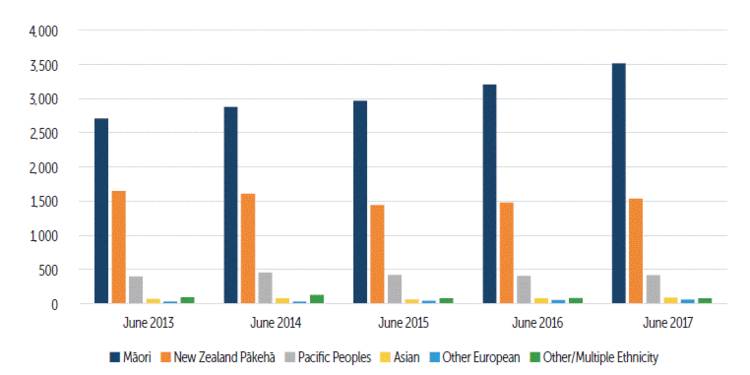

The children of Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, represent a large percentage of the population who are removed from the care of their biological parents due to alleged care and protection issues (see Figure 1). This article explores the decision-making process we, as private practitioners in the field of infant mental health, undertook prior to agreeing to enter into a contractual relationship with Oranga Tamariki (New Zealand Child Protective Services). We questioned: “Is it ethical to undertake parenting assessments and act as expert witnesses in cases which may result in the infant/child being removed from the parent, especially given the history of forced removal of Māori children from their families during colonization and the ongoing imbalance of their representation within the child protection system ?” What follows demonstrates the extent to which we researched the history of Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi), the principles put forth in the body of the treaty, the legislation that grew out of the advocacy for the principles of the treaty, and how well those principles and laws are honoured by the governmental agencies, such as Oranga Tamariki and the Family Court.

We undertook this research, in consultation with our supervisors, to determine whether we felt confident there were no ethical conflicts between the code of ethics of our respective professional bodies and the parenting assessments we were being asked to complete by Oranga Tamariki, a governmental agency overseen by the Ministry of Children. We were aware our reports could be subpoenaed and we might have to testify in Family Court. In this article, we share the reflections and the research we undertook as a way of investigating the ethical implications of taking on the role of assessor and expert witness in child protection cases in Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Figure 1. Distinct Children and Young People in the Custody of the Chief Executive by Primary Ethnic Group—

National—as at the End of Financial Years 2013–2017

Source: https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/cyf/kids-in-care. html#DistinctchildrenandyoungpeopleinthecustodyoftheChiefExecutive1

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Māori were the first people to arrive to what is now known interchangeably as Aotearoa (Land of the Long White Cloud) or New Zealand. According to the agreed-upon oral history of Māori and the evidence gathered from archaeologists and geneticists, the first settlement took place during the thirteenth century AD (King, 2004). The descendants of the first settlers of Aotearoa occupied the land for at least five centuries before the arrival of the first Europeans (Pākehās) in the seventeenth century. These five centuries produced a culturally rich existence, one that was seriously challenged by the eighteenth century, due to exposure to the “cultural, technological and pathogenic impedimenta carried by humankind as a whole” (King, 2004, p. 91).

From the eighteenth century onward, the Māori and the Pākehā have been “pulled steadily toward a ‘permanent and constitutional relationship’ ” (King, 2004, p. 152). On February 6, 1840, at the banks of the river Waitangi, a treaty was signed, which, in the words of the historian, Michael King, “would turn out to be the most contentious and problematic ingredient in New Zealand’s national life.” (p. 157). The original thinking that gave rise to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which was the creation of “a Māori New Zealand in which European settlers had somehow to be accommodated,” shifted and the emphasis was focused on setting the stage for “a settler New Zealand in which a place had to be kept for Māori” (King, 2004, p. 157).

Two Government Systems

Historian Michael King expressed well the dynamics which have led us to reflect on the ethical issues generated by our willingness to complete parenting assessments for Oranga Tamariki. He wrote:

In the words of a later Māori High Court Judge, Eddie Durie, tangata whenua, the people of the land, would now be joined by “tangata tiriti”, the people whose presence was authorised by the Treaty of Waitangi. And the face of New Zealand life would from that time on be a Janus one, representing at least two cultures and two heritages, very often looking in two different directions. (King, 2004, p. 167)

The British Parliament gave the Europeans the responsibility of governing New Zealand in 1852. The decision to place governance in the hands of the Europeans led to a two-tiered governance which persisted. The three principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which were to be upheld, were: protection, participation, and partnership with Māori. However, according to the New Zealand historian, Michael King (2004), by 1913,

there were in effect two New Zealands at this time: the Pākehā [European] one served and serviced by the national and local government administration systems; and Māori New Zealand served by a native school system and little else, but ignored except when national or local government wanted to appropriate land, income (dog taxes, for example) or manpower. (King, p. 246)

The question we had to ask ourselves as we queried the ethics of entering into a contractual relationship with the local governmental system, Oranga Tamariki, which is governed by the national Ministry of Children, was: had this Janus life, this two-tiered governance, changed in the last century?

The Family Group Conference (FGC)

Our research led us to a book titled Returning to the Teachings: Exploring Aboriginal Justice, (Ross, 1996) in which the author stated:

In 1989 the government of New Zealand took a radical step with the passage of the Children, Young Persons and their Families Act. It created a new process called the Family Group Conference…FGCs are based on the teachings of the Māori… (Ross, p. 19)

The author, Rupert Ross, a judge from Canada who had been appointed by his government to explore the possibility of the First Nations people of Canada overseeing their own judicial system, explained how the “radical step” taken by the New Zealand government influenced the Canadian government. New Zealand was a pioneer in experimenting with authentic bicultural governance. FGCs were mandatory for all, not only for Māori. The principle of Whanaungatanga (the importance of kinship and relationships as a way to foster a sense of belonging and well-being) was foundational to the FGC, and the honoring of this principle grew out of what King (2004) called the “revolution” precipitated by the re-emergence of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in the 1960s. To make a principle of supreme value to an indigenous people into the law of the land was revolutionary. It created an ideal to which the country, as a whole, has attempted to live up to in the years that followed.

Our decision to enter into a contractual relationship with the governmental agency, Oranga Tamariki, was based on our knowledge of the efforts made by Māori leaders, both in the past and the present, to shape bicultural governance in New Zealand. (Durie, 1984; Henderson, 1972; King, 2004; Love & Pere, 2004; McNeill, 2009; Rudsen, 1888; Walker, 2006; Williams, 1969).

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, Oranga Tamariki, and Family Court

Our belief that both the government institutions and the Māori are committed to upholding the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi was fortified by the comments and responses included in the Children, Young Persons and Their Families (Oranga Tamariki) Legislation Act 2017. As we read through the comments made by organizations, agencies, and individuals representing the Māori perspective, it became clear there is yet to be a consensus on how to interpret the legislative document. Some commentators (Iwi Leaders Groups on Whanau Ora and Justice, Nga Iwi Nui Tonu o Mokai Patea and Ngai Tamanuhiri te Iwi) stated the term “child-centred” dismissed the importance of the principle of Whanaungatanga. Others stated the child-centred approach is not exclusive of whanau (family), hapu (extended family), and iwi (tribe). For instance, the Te Hunga Roia Māori o Aotearoa (New Zealand Māori Law Society, Inc.) wrote, “Prioritising a child’s connection and culture can still complement the objective that the child or young person is at the centre of the decision-making that affects them” (Oranga Tamariki Legislation Act, 2017).

The response to these views was respectful and demonstrated a willingness to work cooperatively to achieve the stated purpose of “supporting and protecting young children to prevent them suffering or risk suffering harm (including to their development and well-being), through abuse, neglect, ill treatment or deprivation” (Oranga Tamariki Act 2017/1989, s 4(b)), while endeavouring to honor the principles of whakapapa (tracing genealogy-mapping relationships) and whanaungatanga (kinship, family connection) for all. Dr. Rangimarie Pere stated in an interview (2016), “There is a respect we have between us. That is sacred.” This respect was evident in the efforts made to articulate the distrust of the wording and the institution itself and the way those efforts were received.

Additional Safeguards Against Bias

The Oranga Tamariki Bill of 2017 also made it clear that part of Oranga Tamariki’s purpose, duties, and provisions was to provide individualized, comprehensive, professional assessments with a strengthened focus on early intervention and prevention. This was referred to as the “new operating model” (Oranga Tamariki Legislation Act, 2017 (138)) and was in response to the request on the part of multiple Māori organizations. The Ministry of Social Development has also commissioned a Māori health ethics review framework, Te Ara Tika, as a Te Tiriti o Waitangi partnership response. The Te Ara Tika framework (Hudson, Milne, Reynolds, Russell, & Smith, 2010) was developed to address Māori ethical issues by a group of Māori experts, the Putairoa Writing Group. Its basis is tikanga Māori (Māori protocols and lore). Te Ara Tika framework values professional assessment as a way to ensure greater objectivity and lessen the potential for implicit bias (Hudson et al., 2010). These efforts reflect the respect to which Dr. Pere referred and are an indication of why we are asked to conduct parenting assessments of infant/caregiver dyads.

A careful review of the Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, the positive report regarding adherence of the New Zealand government to the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights as well as the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights by Miriama Evans (Epps & Graham, 2011) and the investigation into the implementation, as mandated by law, of the FGC, assisted us to conclude the following: by agreeing to conduct parenting assessments we were adhering to one of the basic ethical tenets of the our professional bodies, which is beneficence. The definition of beneficence given by Forester and Davis (2016) is, “Simply stated it means to do good, to be proactive, and also to prevent harm when possible. Beneficence can come in many forms such as the prevention and early intervention actions that contribute to the betterment of clients” (p. 2).

The FGC appears to have withstood the test of time and remains a means by which, legally, both the rights and needs of the tamariki (infant/child) and those of the whanau (family) and wider hapu (extended family) and iwi (tribe) are taken into consideration. The passage of the Children, Young Persons and their Families (Oranga Tamariki) Act 2017 makes the procedures and policies the law of the land to be upheld by all governmental agencies.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi (The Treaty of Waitangi) was signed on February 6, 1840, on the banks of the river Waitangi. Photo: Shutterstock

Having been a party to many FGCs, we understood the process. This understanding was another component which allowed us to determine it was ethically sound to offer our assessment skills in these fraught situations; we knew our conclusions would be one small part of a larger undertaking to determine who would ultimately be the guardian of the infant. The FGC would occur, and the legal mandate is the whanau (family) is to lead the process. We knew Oranga Tamariki is obliged by law to take into consideration the wishes of the whanau (family).

Family Court, as a branch of the judicial system, is also obligated to uphold the Act and the principles of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi. We were aware of the right of the whanau (family) to contest the decision made by Oranga Tamariki in regard to the care and protection status of the child or to reconsider after having agreed the child was in need of care and protection. These institutional channels to address possible injustices exist in New Zealand (Ludbrook, 2012). We were therefore assured the whanau (family) of the infant/child had the right to redress. These assurances regarding the efforts of the New Zealand justice system to counteract explicit biases formed the foundation of the ethical decision-making process.

This is not to say we have blind faith in the governmental agencies and institutions. We are fully aware of the ongoing, multiple breaches of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi since its signing in 1840 and the implicit biases which persist when one ethnic group is privileged over another (Andrews-Puketapu, 2018; Rusden, 1888).

The African American political scientist and founder of the Democratic Knowledge Project, Danielle Allen (2010), wrote:

The simple fact of the matter is that the world has never built a multiethnic democracy in which no particular ethnic group is in the majority and where political equality, social equality and economies that empower all have been achieved. (para. 4)

The attempt to build a multiethnic democracy is New Zealand’s challenge. Māori organizations and governmental institutions have worked hard to establish, over time, a set of shared beliefs and practices (Durie, 1984; McNeill, 2009; Walker, 2006; Williams, 1969). Dr. Rangimarie Pere stated, “I would find it terribly boring if only Māori people existed” (2016). She understood that “resentment fuels polarisation” (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018). This fruitful cross-pollination makes us proud to be members of our respective professional bodies and democratic citizens of New Zealand, a country whose revolutionary honoring of indigenous values has been looked upon by other democratic countries as a model for their own evolution toward a multiethnic democracy.

Reflective Supervision/Consultation

As part of the process of ethical decision-making, we worked with our supervisors to identify the areas which required clarification. First, we asked the following question: who is our client and what does that mean in terms of the ethical obligations we have to our client? When contracted by Oranga Tamariki, legally, our client is Oranga Tamariki and ethically our client is the infant who is under the care of the chief executive of Oranga Tamariki. Given that our services are contracted by Oranga Tamariki, there is “no contractual relationship between counsellor and counsellee” (Ludbrook, 2012, p. 130). The fact that there is no contractual relationship between the counsellee (the infant) and us does not mean, however, there is no obligation for us to follow the Code of Ethics of our professional bodies. As the acting “parent,” the chief executive dictates the parameters of the professional/client relationship. Our remit is to complete a parenting assessment. We are not asked to counsel the parent.

By clearly identifying the client, Oranga Tamariki assists us in avoiding the following unethical situation as put forth by the author of Counselling and the Law: A New Zealand Guide:

Counsellors should be wary of accepting referrals where they are asked to counsel both a parent or carer whose parenting ability is a cause of concern, and a child or children of that parent or carer. A conflict of interest between the parent’s need and the child’s welfare and protection can easily arise and the counsellor may focus on the issues of the parent rather than on the safety and welfare of the child…There is a real danger that the focus on the parent’s coping ability may deflect attention from the risks of the child.” (Ludbrook, 2012, p. 246)

We seek to ensure that the protocols are adhered to by the Oranga Tamariki social worker. Our goal is to work together as a team to undertake an ethically sound, legally correct approach to a difficult and painful situation. We do our utmost to maintain a dialectical stance, which upholds the rights of the infant (Mares, Newman, & Warren, 2005) and those of the whanau (family).

Given the potentially fraught nature of these cases, our supervisors deem it appropriate for us to work together when we conduct the assessments. The purpose of this decision is to have another mind present, another experienced professional to offer another set of thoughts and, most important, someone whose presence would help us be aware of any possible blind spots, implicit biases, or tendency to collude (Kaye, 2014; Peterson, 1992).

One of the goals of our regular reflective supervision/consultation sessions is for us to ensure we deliver a relationally focused, culturally responsive intervention approach (Andrews-Puketapu, 2018; Kaye, 2014). Authors Fitzgibbons, Smith, and McCormick (2018), in an article titled, “Safe Harbor: Use of the Reflective Supervisory Relationship to Navigate Trauma, Separation, Loss, and Inequity on Behalf of Babies and Their Families,” had this to say about the reflective supervision/consultation process:

Of particular note to practitioners and systems working with infants, children and families impacted by traumatic separation, [reflective supervision/consultation] has been considered a trauma informed practice (Badeau, 2015); an approach to mitigating vicarious trauma as well as staff turnover, and a means to ensure best practice. It is critical that children and families experiencing trauma and separation receive service provision from practitioners who value and practice cultural humility… Cultural humility is a dedication to life-long self-evaluation, identification, and rectification of power and privilege imbalances in the practitioner-client relationship… (p. 75)

We choose to use the Parent Child Interaction Assessment Feeding and/or Teaching Scale (Oxford & Findlay, 2013), a microanalytical observational tool designed to assist the practitioner to be objective, alongside other assessment formats and tools. With support from our supervisors, we are able to remain empathetic as we conduct the assessments. Ultimately, we believe we uphold the core values and the ethical principles of our respective Code of Ethics, as we work to synthesise a clinical opinion that holds both the caregiver and the infant in mind.

It is difficult to be empathic and objective. With practice and with adequate reflective supervision, it is possible. Ludbrook (2012) gave an explanation for the tension a counsellor must hold when asked to testify in court:

Research in this country and overseas indicates that many counsellors feel quite anxious and uncomfortable about appearing in court as a witness. This is hardly surprising, because the ethos of counselling is directly contrary to that which informs the adversarial legal process. (p. 205)

The “ethos of counselling” can be maintained by engaging in reflective supervision/consultation to facilitate adherence to the core values, ethical principles, and guidelines of the respective Code of Ethics in all interactions.

Our endeavor to adhere to principles of our professional practice is supported by careful adherence to the specific policies and procedures of our service: we spend time in meeting the infant and the caregiver, we go over our consent form with the caregiver of the client because, despite this not being a legal obligation (Ludbrook, 2012), it is an ethical one. We help the caregiver understand the nature of our contract with Oranga Tamariki and ensure the caregiver is aware that the information we gather will be shared with Oranga Tamariki. We explain in clear language the nature of the assessment process and the purpose of our involvement. These efforts are in alignment with the principle that counsellors/therapists shall obtain informed consent from clients when writing reports for third parties.

The three principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which were to be upheld, were: protection, participation, and partnership with Māori. Photo: Shutterstock

Conclusion

As a result of the ethical decision-making process described above, we achieved clarity regarding the following key issues:

- The infant is our client. Given infants are nonverbal, their rights often are overlooked when faced with the substantial needs of the caregiver (Ludbrook, 2012; Mares et al., 2005). Mares, Newman, and Warren (2005) described the rights of the infant as being particularly vulnerable to being lost in disputes. They made the following statement about a basic belief in the field of infant mental health:

At its core is the recognition that infancy is a foundational developmental period, physically, psychologically and socially, that infant development occurs within the context of key caregiving relationships, and that infants have abilities, drives, wants and needs but also rights, just as more verbal older children and adults do. (p. 4)

- By using objective microanalytical observational assessment tools (Parent Child Interaction Assessment Feeding and Teaching Scales (Oxford & Findlay, 2013) and Newborn Behaviour Observation System-NBO (Nugent, Keefer, Minear, Johnson, & Blanchard, 2007) which focus on the nonverbal cues of the infant, we attempt to uphold the rights of the infant by giving her or him an equal say in the process. This effort reflects our commitment to the core values of the field of infant mental health and our respective professions.

- If we decline to use our skills to assist Oranga Tamariki in its decision-making process, we would be demonstrating doubt in the intention of a governmental agency to uphold the law, a reluctance to provide equitable counselling/therapy services to a client, and a lack of faith in the willingness of the institution of the Family Court to abide by the law of the land.

To have contributed, in even a small way, to a decision which will have far-reaching implications in the life of an infant and that child’s caregiver is a burden, particularly when the field we specialize in recognizes the vital importance of the primary attachment figure and the Whanaungatanga (kinship) in the development of the infant. To reflect in depth and, from this reflection, determine we are able to remain true to the Code of Ethics of our professional bodies and, more important, to our personal standards of how one human being should conduct herself in her interactions with another human being, allows us to carry that burden. The reflection process has given us a greater appreciation of how codes of ethics, codes of conduct, treaties, covenants, laws, and court procedures are democratic processes designed to provide us with scaffolding so we might live up to the ideals we hold as individuals, as associations, and as nations.

The descendants of the first settlers of Aotearoa, New Zealand occupied the land for at least five centuries before the arrival of the first Europeans (Pakehas) in the seventeenth century. Photo: Shutterstock

Authors

Sarah Haskell, NZROT, DipCOT, DipHE, MSc, is an occupational therapist with a master’s degree in infant mental health. She was the manager of Infant, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services for the West Coast for 12 years, and she and Heidi Pace set up the first Infant Mental Health Programme on the South Island of New Zealand.

Heidi Pace, MNZAC, MA, IPMHF, has a master’s degree in counselling psychology with specialisation in cross-cultural counselling and depth psychology. She is a graduate of the Infant Parent Mental Health Fellowship, University of Massachusetts, Boston/Napa Postgraduate Programme.

Suggested Citation

Haskell, S., & Pace, H. (2019). Ethical considerations in cross-cultural parent–child assessment in New Zealand. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(1)36–42.

References

Allen, D., (2017, August 13). Charlottesville is not the continuation of an old fight. It is something new. Washington Post. Source link

Andrews-Puketapu, G., (2018). Māori inequities in the westernised health setting-a counsellor’s perspective. Counselling Aotearoa, October. Source link.

Durie, M. (1984, March). Te taha hinengaro: An integrated approach to mental health. Hui Whakaoranga: Māori Health Planning Workshop. Auckland, New Zealand: Department of Health.

Epps, V., & Graham, L. (2011). International law. New York, NY: Aspen Publishers. Fitzgibbons, S. C., Smith, M. M., & McCormick, A. (2018). Safe Harbor: Use of the reflective supervisory relationship to navigate trauma, separation, loss, and inequity on behalf of babies and their families. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 39(1), 74–82.

Forester-Miller, H., & Davis, T. E. (2016) Practitioners guide to ethical decision making (rev.ed.). Source link

Henderson, J. M. (1972). Ratan: The man, the church, the political movement. Wellington, NZ: A. H. & A. W. Reed.

Hudson, M., Milne, M., Reynolds, P., Russell, K., & Smith, B., (2010). Te ara tika guidelines for Māori research ethics: A framework for researchers and ethics committee members. Wellington, NZ: Health Research Council.

Kaye, V. (2014). The Te Rito bicultural competency module: the treaty and you—linking what you do each day with the articles. Wellington, New Zealand: Kia Maia Bicultural Communications.

King, M. (2004). The Penguin history of New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Penguin Books.

Levitsky, S., & Ziblatt, D. (2018). How democracies die. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Love, A. M. C., & Pere, R. R. (2004). Extensions on te wheke (Vol. 4). Lower Hutt, New Zealand: Open Polytechnic of New Zealand.

Ludbrook, R. (2012). Counselling and the law: A New Zealand guide. Auckland, New Zealand: Dunmore Publishing.

Mares, S., Newman, L., & Warren, B. (2005). Clinical skills in infant mental health. Camberwell, Australia: ACER Press.

McNeill, H. (2009). Māori models of mental health. Te Kaharoa, 1(2), 96–115.

Nugent, K. J., Keefer, C. H., Minear, S., Johnson, L. C., & Blanchard, Y. (2007). Understanding newborn behavior & early relationships: The newborn behavioral observations (NBO) handbook. Baltimore, Maryland: Brookes.

Oranga Tamariki Act 1989/2017.

Oxford, M., & Findlay, D. (2013). Caregiver/parent-child interaction feeding manual. Parent child interaction program. Seattle, Washington: School of Medicine, University of Washington

Pere, R. (2016, September 20). The right to be me. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=79II_eXKoWo

Peterson, M. (1992). At personal risk: Boundary violations in professional client relationships. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Ross, R., (1996). Returning to the teachings: Exploring aboriginal justice. London, England: Penguin.

Rusden, G. W. (1888) Aureretanga: Groans of the Maoris. London, UK: William Rodgeway

Walker, R. (2006). Māori sovereignty, colonial and post-colonial discourses. In H. Paul (Ed.), Indigenous peoples rights: In Australia, Canada and New Zealand (pp. 108–122). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Williams, J. A. (1969) Politics of New Zealand Maori: Protest and cooperation. Auckland, NZ: Oxford University Press.