Julie Poehlmann-Tynan, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Abstract

Millions of U.S. children are separated from a parent each year because of parental incarceration in prison or jail. The vast majority of people who go to jail or prison will be released eventually, making parental reentry and parent–child reunification a common process in families affected by incarceration. Despite the importance of the reentry period, few studies have focused on how young children cope when a parent returns from jail or prison. This article summarizes what little researchers know about children’s reunion with their parents following parental incarceration, parental experiences of reentry, and what can help children and families.

More young children in the United States, especially poor children of color, have a parent involved in the criminal justice system than ever before. By the time they are 14 years old, 5 million U.S. children will lose a resident parent to prison or jail, with most parental incarceration occurring when children are young (Murphey & Cooper, 2015). Although a growing body of research and intervention work focuses on children’s adjustment to enforced parent–child separation because of parental incarceration, little attention has been paid to children’s reunion with their parents or to children’s experiences of parental community supervision. This lack of information is particularly unfortunate because nearly everyone who goes to jail or prison eventually returns to the community (Travis, 2005). In 2016 alone, state and federal correctional facilities released 626,000 individuals (Carson, 2018); previous estimates indicated that most people incarcerated in state or federal prison are parents (Glaze & Maruschak, 2008). At year-end 2016, 874,800 people were on parole, or the conditional release of an individual into the community after incarceration while still under correctional supervision (Kaeble & Cowhig, 2018). In addition, more than 9 million individuals are admitted to and released from jails each year, with the majority being parents (Sawyer & Bertram, 2018; Zeng, 2019). In this article, I briefly summarize young children’s reactions to their parents’ incarceration, explore relevant research on parental reentry and reunification with children following incarceration, and present what little researchers know about children’s responses to reunion with reentering parents. I conclude with suggestions for helping children and families during the reunion period.

Young Children’s Emotional Reactions to Parental Incarceration

In the first study to document young children’s attachment relationships with their incarcerated mothers and caregivers1, I also examined children’s emotional and behavioral reactions to separation from their imprisoned mothers (Poehlmann, 2005b). The study included 60 children, 2.5–7 years old, and their families during the mother’s incarceration in a state prison; children were most often staying with their grandmothers during the incarceration. I measured children’s representations of attachment relationships with mothers and caregivers using an adapted version of the Attachment Story Completion Task (Bretherton, Ridgeway, & Cassidy, 1990). I also asked caregivers to complete a checklist focusing on children’s immediate reactions to separation from their mothers because of incarceration. Caregivers reported that children’s reactions to separation included worry, sadness, confusion, anger, loneliness, developmental regression, and sleep problems. In addition, 32% had subaverage cognitive test scores (77–84) and an additional 10% scored in the delayed range (at or below 76). However, just over half of the children had not received intervention services (Eddy & Poehlmann, 2010; Poehlmann, 2005a).

In an extension of the study, my colleagues and I assessed 77 children, 2–6 years old, and their families during the father’s incarceration in jail (Poehlmann-Tynan, Burnson, Weymouth, & Cuthrell, 2017). We used the Attachment Q-Sort (Waters & Deane, 1985) to assess children’s organization of attachment behaviors toward their caregivers, and we used the same emotions checklist as the prior study. Most children were staying with their mothers, although many grandparents were also involved in children’s daily care. Caregivers reported that children experienced separation reactions similar to the previous study. In both studies, insecure attachment to caregivers was more common than in normative samples (63% insecure, Poehlmann, 2005b; Attachment Q-Sort scores ranging from -0.43 to 0.69, with a mean of 0.20, similar to studies with clinical samples, Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2017) and children were exposed to multiple risk factors including poverty, parental mental illness and drug abuse, and repeated separations from parents. The children were not studied longitudinally, however, so we do not know how the children reacted to reunion with their parents. Although neither study focused on children younger than 2 years old at the time of our initial assessments, some of the children were infants when their parents left for prison or jail.

1 The term caregiver in this article refers to the adults who are providing primary care for the child during the parent’s incarceration and/or reentry.

Research on Reentering Parents

A number of noteworthy studies have examined how incarcerated parents adjust during reentry from prison. Although none focused specifically on parents of infants or toddlers, there are still lessons that can be learned about what helps reentering parents succeed. The Multisite Family Study on Incarceration, Parenting, and Partnering, was a longitudinal study of 1,482 incarcerated fathers and their female partners. In their analyses, McKay, Comfort, Lindquist, and Bir (2019) found that when children were younger, fathers reported more joyful reunions with them and an increased likelihood of living with them. They also found that correctional and community supervision policies and practices did not support incarcerated fathers’ family ties, instead focusing on surveillance and removal. The study also found that the financial strains of having a family member in prison are heavy, similar to previous findings (Christian, Mellow, & Thomas, 2006). Family members paid ridiculously high amounts for phone calls, fees, and visits; yet frequency of contact was an important predictor of fathers’ post-release success.

Family members paid ridiculously high amounts for phone calls, fees, and visits; yet frequency of contact was an important predictor of fathers’ postrelease success.

Another example of a longitudinal multistate project focusing on reentry is the Returning Home study, conducted by the Urban Institute from 2001–2006 about incarcerated individuals’ reintegration following release from state prisons in Maryland, Illinois, Ohio, and Texas. In her analysis of the Returning Home data, Visher (2013) found that fathers who communicated more with their children during their last 3 months in prison, including visits and letters, were more engaged in their children’s lives following release from prison. Moreover, 3 months into the reentry period, fathers who were more engaged in their children’s lives reported fewer depressive symptoms, worked more hours per week, and were less likely to recidivate or violate the terms of their parole. In another analysis, Naser and La Vigne (2006) found that formerly incarcerated individuals relied on family members for housing, financial support, and emotional support following their release from prison. They relied on family even more than they had expected during their incarceration. La Vigne, Brooks, and Shollenberger (2009) examined Returning Home data on women, most of whom were mothers. Although many mothers had a family support system on the outside, it was not as strong as that reported by fathers. In addition, reentering women were much less likely than men to receive financial support from their parents, although they received such support from their partners and children.

The Boston Reentry Study, another longitudinal study focusing on reentering adults (Western, 2018) followed 122 men and women (two thirds of whom were parents) as they prepared for release from Massachusetts state prisons through their first post-release year. Despite a history of trauma and challenging life circumstances, which often occurred in their families of origin, support to reentering adults was most often provided by the formerly incarcerated adult’s female relatives, such as mothers, grandmothers, aunts, and sisters. For parents in the study, children’s caregivers were generally not a significant source of support in the first year following release from prison; rather, they acted as gatekeepers of the reentering parent’s access to children.

In addition to these large studies, smaller studies have also investigated parental anticipation or experiences of reunion. For example, in a study of 98 imprisoned mothers with young children, Runion (2014) found that most (93%) mothers planned to reunite with their children and had specific reunion plans, with about half reporting self-focused plans (e.g., self-recovery, seeking employment or housing) and half reporting child-focused plans (e.g., planning activities with children, making custody changes). In addition, Charles, Muentner, and Kjellstrand (2019) reported on a qualitative study of 19 fathers who had at least monthly contact with their children and who had been released from prison in the past year. The study found that despite multiple reentry challenges related to poverty and inequality, fathers reported being deeply committed to their children.

How Children Cope With Reentry

Given the dearth of research on young children’s reunion with formerly incarcerated parents, in the next sections I summarize findings from studies focusing on: (1) the sequelae of paternal recidivism for young children’s behavior, (2) children’s perspectives of anticipating paternal release, and (3) infants and toddlers reentering after their stay with incarcerated mothers in a prison nursery.

Sequelae of Paternal Recidivism for Young Children

As a key source of longitudinal data on children with incarcerated parents, the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing (FFCW) study includes a population-based sample of nearly 5,000 urban children born between 1998–2000 to mostly unmarried parents. Children’s mothers and fathers were interviewed right after the child’s birth and again 1, 3, 5, 9, and 15 years later, including information about parental incarceration at each study wave. Using the FFCW dataset, Wildeman (2010) found that when a child’s father had been incarcerated, boys (but not girls) showed increased symptoms of aggression when they were between 3 and 5 years old, controlling for other risks. It is important to note that the first paternal incarceration in a boy’s life was associated with an increase in boys’ aggression while the father was gone, and then a decrease when the father came home. In contrast, boys who had already experienced their father going to jail or prison were more affected by a new incarceration, thus showing the importance of paternal recidivism for the development of aggression in young boys. Although many additional analyses of FFCW data have examined child well-being in the context of paternal and maternal incarceration (Turney & Haskins, 2019), few of these analyses have focused on children during infancy or toddlerhood. Moreover, because of the data structure and questions asked, it is difficult to determine exact periods of parental reentry.

Children’s Perspectives on Anticipating Paternal Release

A qualitative study looked at older children’s expectations for reunion with their incarcerated fathers. Yocum and Nath (2011) interviewed 17 children, 4–15 years old, and their mothers who were anticipating the release of fathers within the next year. Younger children were not assessed because they would not have been able to participate in the interviews. All children and mothers who participated in the study said that they wanted fathers to be involved with children after release from prison. However, these wishes were combined with some uncertainty, except for younger children. Younger children described the kinds of activities they wanted to do with their fathers following his release, such as “fun things” like going to movies, playing sports, or going to the park and “everyday things” like eating together, watching TV, or talking. The authors concluded that clarifying and negotiating children’s and families’ expectations are important for successful child−father reunion. However, there was no follow-up regarding children’s actual reunion experiences. One can speculate that there may be different expectations for families with infants or toddlers upon reunion, including establishing or reestablishing attachment relationships, creating or reestablishing routines for sleep, meals, and transitions, and coping with potential behavioral issues. Clearly more research needs to be conducted on parental reentry with very young children.

Infants and Toddlers Reentering From a Prison Nursery

A very small proportion of infants with incarcerated mothers live with their mothers in prison nursery programs rather than being separated from their mothers and placed in the community during her incarceration. Byrne and colleagues conducted a landmark longitudinal study on the development of the children during and following their prison nursery stay (Byrne, Goshin, & Joestl, 2010). While in the nursery, more infants developed secure attachments to their mothers than expected, given the mothers’ high risk status (Byrne et al., 2010). Mothers who had been in the nursery program had low rates of recidivism within 3 years after discharge, with only 4% of women returning to prison for new crimes (Goshin, Byrne, & Henninger, 2013). In addition, infants who were discharged into the community with their mothers fared well. About 59% of children were discharged with their mothers, and 83% of these remained with her at the end of the third reentry year (Byrne, Goshin, & Blanchard-Lewis, 2012). Of the 40% of children who began living in the community prior to their mother’s prison release, most were with family caregivers at the end of the first reentry year. Although other studies focusing on prison nurseries exist, the majority of outcome variables focus on maternal recidivism.

What Can Help Children and Families With Reunion

The reentry period can be made more successful through actions taken during the incarceration period, as well as policies and practices that occur following release into the community.

A key component of the post-release period is the prevention of parental recidivism, either from a new offense or from a technical violation of the terms of probation or parole. In a classic study of recidivism, two thirds of state prisoners were rearrested and more than half returned to prison within 3 years of release (Durose, Cooper, & Snyder, 2014). These high recidivism rates have implications for young children’s well-being, especially the development of aggression (Wildeman, 2010). Although being a parent is not consistently related to rearrest and reoffending (Folk, Tangney, & Stuewig, in press; Goshin & Sissoko, in press), children provide motivation for parents to succeed during incarceration and reentry (Charles et al., 2019). For mothers, having a child at home may decrease the chance of rearrest within the first year following jail incarceration or jail-based substance abuse treatment (Freudenberg, Daniels, Crum, Perkins, & Richie, 2005; Scott, Grella, Dennis, & Funk, 2016).

Services and Support During the Incarceration Period

Many services and supports are needed to make the reentry period successful, and it is best that they start at the beginning of the incarceration period.

Reentry Planning

Reentering individuals who receive planning assistance have more successful reentry experiences, including lower recidivism rates (La Vigne, Davies, Palmer, & Halberstadt, 2008). Planning includes identifying community supports, as well as assistance with important processes such as finding work, a place to live, alcohol or drug treatment, counseling, health care, and child care. Reentry planning should begin as soon as the individual is incarcerated, and it should also include the family. Thus, prisons and jails should inquire about parental status at intake and provide services related to parenting and strengthening family relationships starting from day one (Shlafer, Hindt, & Saunders, this issue, p. 14).

Boys who had already experienced their father going to jail or prison were more affected by a new incarceration, thus showing the importance of paternal recidivism for the development of aggression in young boys.

Adjusting Expectations and Providing Support

Several studies have found that children’s expectations about their relationships with incarcerated parents in the post-release period are important. Caregivers can gently shape children’s expectations by talking about what the parent needs to do, how much time the parent will have for the child, where the child will live, and what activities that the child might reasonably expect to do with the formerly incarcerated parent. Meeting children’s expectations and hopes about reconnecting during reunion can help them develop trust and feelings of security. Although the research focusing on children’s expectations has been conducted with older children, developing trust and feelings of security are essential for children of all ages. Caregivers can help support younger children’s feelings of trust for the incarcerated parent during the separation period, even when children are very young. Caregivers can also encourage parent–child contact that is positive and supportive. Adults can adjust their expectations of the reunion period by realizing that reentering parents often must rely heavily on family support, especially for housing and other forms of stability. The support can be financial, tangible, emotional, or a combination of these, so maintaining or repairing relationships is an important part of preparing for reunification.

At-home caregivers should talk with children about the parent–child separation and help the child understand that the situation is temporary, not her fault, that the parent still loves her, and that she is not alone (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., in press; Sesame Workshop, 2013). The underlying messages about maintaining an attachment to the incarcerated parent are similar to messages given to children who are separated from a parent for other reasons, such as parental deployment (Yeary, Zoll, & Reschke, 2012). Messages focusing on how the absent parent loves and thinks about the child are helpful, as well as indicating that the parent and child will be together again in the future. Moreover, assisting children by labeling their feelings and using language to help them process their experiences are essential in helping young children develop some understanding of and eventual words for the separation experience, in addition to fostering emerging self-regulation. In helping very young children adjust to separation from parents, Yeary et al. (2012) recommended using multiple senses as well as digital technology, including recording audio or video of a parent reading to the child. These positive connections are thought to help decrease children’s stress and help the child know that he is loved.

Helping Children and Parents Stay in Contact During Incarceration

A common finding that has emerged from research on parental reentry is that the quality of the parent–child relationship that develops during the incarceration period, typically facilitated through mail exchanges, phone calls, and visits, is associated with the quality of that relationship following release (La Vigne, Naser, Brooks, & Castro, 2005). Although there are many barriers to parent–child connections during incarceration, including financial, time, social, emotional, and relationship-oriented challenges (see Poehlmann-Tynan & Pritzl, 2019, for a review), young children benefit from child-friendly in-person visits; sending notes, letters, drawings, cards or emails; and video chats. Developmentally, it is difficult for very young children to have a telephone conversation, even though it is the most common way for jailed parents to communicate with their children (Shlafer, Davis et al., 2020) (see Box 1).

Resilience processes often arise in families who are able to maintain positive relationships despite the stressors related to parental incarceration and reentry.

Researchers have found that more family contact is associated with lower recidivism for incarcerated individuals (Bales & Mears, 2008), although young children often find visits behind Plexiglas to be stressful (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2015; see next section). Although more parent–child contact improves success in rebuilding parent–child relationships during reentry (La Vigne et al., 2005), caregivers act as the gatekeepers of young children’s contact with their incarcerated parents. Thus, it helps to support caregivers in their role and facilitate their perspective taking (Kerr et al., 2020). When caregivers become aware of how crucial their role is in supporting children’s emotional development and relationships with their incarcerated mothers or fathers, caregivers may also become more willing to facilitate positive parent–child contact.

Extra Support for Children Under 5 Years Old

Young children with incarcerated parents are more likely than older children to experience additional trauma, making them particularly vulnerable (Turney, 2018). In addition, young children—especially toddlers—have a particularly difficult time visiting in corrections facilities that have glass or other barriers between incarcerated individuals and visitors (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2015). Young children are more likely to react with anger or crying, and they have a particularly hard time waiting for visits to begin at corrections facilities. Moreover, compared to children who are 5–8 years old, children 2–4 years old are more likely to have insecure attachments with their caregivers during parental incarceration (Poehlmann, 2005b; Poehlmann-Tynan et al., 2017). Thus, the child’s age and developmental competencies should always be considered when determining how best to help. During visits between children under 5 and their incarcerated parents, caregivers need to be highly involved in helping children stay engaged, prompting children about what to communicate with the incarcerated parent, and general structuring and scaffolding (Skora Horgan & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2020).

“Enhanced Visits” intervention for children with incarcerated parents and their families. For 3 months, we provide children 3–12 years old with a tablet, internet access if they do not already have it, and free in-home video chat with their incarcerated parents, up to daily if desired (Charles et al., 2020). We also provide visit coaching for parents and caregivers, based on an attachment intervention called “savoring” that we hope fosters parental reflective functioning (Kerr et al., 2020). We are currently conducting a pilot feasibility study of the intervention.

David Nevala for the Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Young children are more likely to live with reentering parents than older children, so they are directly affected by the benefits and challenges of reunion (Goshin & Sissoko, in press; McKay et al., 2019). Although I have emphasized provision of support to ameliorate reentry challenges, it is also important to keep in mind that returning parents report more joyful reunions with younger children and that younger children have fewer doubts and resentments about their returning parents’ ability to live up to their expectations (McKay et al., 2019; Yocum & Nath, 2011).

How parents and caregivers talk to young children whose parents are incarcerated about the parent’s absence and return affects how children adjust. Along with other advisors, I worked with Sesame Workshop to develop materials for young children with incarcerated parents and their caregivers (see Box 2). In a study evaluating the Sesame Street incarceration materials, my colleagues and I found that the materials helped caregivers find the words needed to talk to young children about their parents’ incarceration (Poehlmann-Tynan et al., in press).

Supporting Caregivers

In one of my recent co-edited books on children with incarcerated parents that summarized interventions, we could not even include a chapter on interventions for caregivers (those providing the child’s primary care in the absence of the parent) because so few interventions on caregivers exist (Wildeman, Haskins, & Poehlmann-Tynan, 2017). Yet in families affected by parental incarceration, the importance of the caregiving context—quality of the child–caregiver relationship, caregiver mental health, and family economic well-being—cannot be overstated (Poehlmann-Tynan & Eddy, 2019).

Because there are so few studies on children reuniting with their incarcerated parents, it helps to look at parallel literatures. In a recent review of 27 studies focusing on children’s coping with reintegration with their military parents following separation because of deployment, three themes emerged: A child’s coping is influenced by (a) the child’s age and development, (b) the mental health and coping of the child’s primary caregiver and returning parent, and ( c ) the preexisting resilience and vulnerability factors relative to resources of the child and family (Bello-Utu & DeSocio, 2015). These considerations are also likely to be important in families experiencing parental reentry from prison or jail.

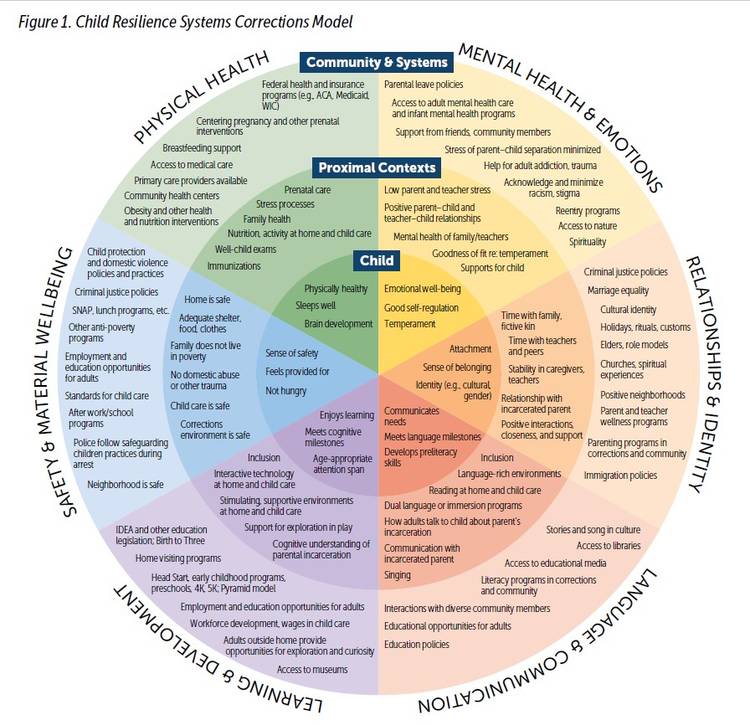

Contextual Model of Resilience

Resilience processes often arise in families that are able to maintain positive relationships despite the stressors related to parental incarceration and reentry. Figure 1 depicts a contextual model of resilience that shows potential resources and areas of resilience in multiple developmental domains for young children whose families are involved in the criminal justice system. Although developed independently, it is consistent with the Strengthening Families Protective Factors Framework (Center for the Study of Social Policy, n.d.). Approaching work with corrections can be strengthened by using such models and frameworks, as doing so makes it easier to communicate goals and how professionals, including corrections staff who interact with parents, caregivers, and children, can work with them in a way that shows that they are valued.

Services and Support During Reentry

In addition to supports during the incarceration period, it is essential to have supports and services in place during reentry.

Case Management

Services during reentry need to be both focused and coordinated (Byrne et al., 2012; Fontaine, Cramer, & Paddock, 2017). Reentry challenges include needs for housing, employment, drug and alcohol rehabilitation, health and mental health services, and emotional support. Case managers, family navigators, and advocates can help returning individuals and their families and communities become less fragile by connecting services across multiple systems. Advocating for safe housing, health care, and income support, especially for people of color, can help in addressing and decreasing racial disparities (Western, 2018).

One way to combat racism, discrimination, and stigma is for case managers and family navigators to provide accurate information about housing options, driver’s licenses, voting, and federal and state benefits to the formerly incarcerated. Unfortunately, it is a common problem for reentering individuals to be denied—erroneously–certain services because of their criminal record. To assist with this process, the National Reentry Resource Center (2020) provides a series of online fact sheets called the “Reentry Myth Buster series,” designed to clarify federal policies about issues such as housing, child welfare involvement, social security benefits, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, for those returning from incarceration.

Photo: David Nevala for the Center for Healthy Minds, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Recognizing and Facilitating Family Support

In the Returning Home study, 71% of formerly incarcerated individuals said that family emotional support was important in helping them succeed in the community (Naser & La Vigne, 2006), similar to the findings in the Boston reentry study (Western, 2018), and the Multisite Family Study (McKay et al., 2019) as well as studies examining reentry from jails (Spjeldnes, Jung, Maguire, & Yamatani, 2012). Policies and practices in the criminal justice system, including those of prison, jail, probation, and parole systems, should foster family ties and recognize the importance of family support during the reentry period (McKay et al., 2019). Some studies have found that positive family support during reentry especially mitigates risk factors related to racial and economic inequities, making it a resource that society cannot ignore (Spjeldnes et al., 2012). For reentering men, family of origin support appears particularly important, whereas for reentering women, intimate partner support appears most salient (Cobbina, Huebner, & Berg, 2012).

Adapted with permission from Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Eddy, J. M. (2019). A research and intervention agenda for children with incarcerated parents and their families, Figure 24.1. In J. M. Eddy and J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds), Handbook on children with incarcerated parents, 2nd edition (pp. 353–371). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Boosting Parenting Resources

Returning parents must meet their own needs and their children’s needs. With this in mind, Fontaine and colleagues (2017) recommend providing curriculum-based parenting classes, support groups, child support assistance, and child care assistance to returning fathers. While there are a growing number of parenting classes for parents in prisons, few of these classes are available for reentering parents. Offering evidence-based parenting programs during reentry is particularly important because parents have the opportunity to practice their skills and because children (especially boys) are more likely to develop behavior problems such as aggression (Wildeman, 2010). In addition, support groups and peer mentoring—often involving others with lived experience as mentors and guides—are effective in helping reentering parents succeed.

In their qualitative study, Goshin and Sissoko (in press) found that mothers on community supervision (i.e., parole or probation) indicated that they had to adjust how they mothered their children because of limited resources. In conserving limited parenting resources, sadly, mothers felt that they had to turn down requests from their adolescent and adult children for help, such as living together, so that they could focus on the youngest child’s needs. Every mother interviewed who was a primary caregiver lived with her youngest child, even though she had one or more older children living elsewhere. Mothers described their infants and toddlers as a source of strength, and they were often desperate to keep the youngest in their care. Rather than receiving support from mothers, adult children often provided support to mothers, such as temporarily caring for their younger siblings. Extended family and community members can help these situations and alleviate some of the burden on adult children or teens. With adequate access to resources, it may be possible for reentering parents to have enough to share with all of their children.

Changing Parole and Probation

The average length of parole and probation in the U.S. is about 2 years (Kaeble & Bonczar, 2016). Western (2018) recommended shortening community supervision periods to a maximum of 18 months. In addition, several scholars have discussed changing the focus of reentry work from surveillance to supporting individuals and their families.

By neglecting or undermining the interconnectedness of criminal justice system involvement and family life, such policies may actually prevent criminal justice agencies from moving the needle on their most widely accepted metric (avoidance of reincarceration)—while also thwarting the efforts of human services systems focused on stabilizing families, promoting positive parenting, and lifting women and children out of poverty. (McKay et al., 2019)

Decreasing Reliance on Incarceration and Community Supervision

In addition to supporting children and families as outlined above, it is also important to decrease reliance on incarceration as the “go to” sanction across the U.S., whether at the federal, state, county, or city level. Because parental incarceration in prison or jail harms children, on average, it is essential to recognize the intergenerational consequences of mass incarceration and costs to society, especially for its most vulnerable members (Wakefield & Wildeman, 2018). Decreasing the length of incarceration and community supervision, and refocusing from sanctions to support, are imperative.

In sum, there are many ways to support very young children, reentering parents, caregivers, and extended family as they reunite following parental incarceration. Children and families adjust better during the reunion period when they have access to services and supports during incarceration as well as the reentry period. In all of these efforts, it is essential to try to eliminate systemic racism and economic inequities to ensure that young children with incarcerated parents are not subject to the same negative forces as their parents.

Author

Julie Poehlmann-Tynan, PhD, is the Dorothy A. O’Brien Professor of Human Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She is an affiliate of the Institute for Research on Poverty and the Center for Healthy Minds and a licensed psychologist. Through numerous publications and outreach efforts during the past 20 years, she has brought the attention of child development and family studies communities to the issues of children with incarcerated parents and children raised by their grandparents. Her research has been funded by the National Institutes of Health, the Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, the Department of Justice, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Mind and Life Institute. Dr. Poehlmann-Tynan served as an advisor to Sesame Street to help develop and evaluate their Emmy-nominated initiative for young children with incarcerated parents called Little Children, Big Challenges: Incarceration. She has more than 90 publications and is the editor of three monographs, a book, and a handbook focusing on children with incarcerated parents. The handbook is now in its second edition.

Suggested Citation

Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2020). Reuniting young children with their incarcerated parents. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(4), 30–39.

References

Bales, W. D., & Mears, D. P. (2008). Inmate social ties and the transition to society: Does visitation reduce recidivism? Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 45(3), 287–321.

Bello-Utu, C. F., & DeSocio, J. E. (2015). Military deployment and reintegration: A systematic review of child coping. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 28(1), 23–34.

Bretherton, I., Ridgeway, D., & Cassidy, J. (1990). Assessing internal workingmodels of the attachment relationship: An attachment story completion task for 3-year-olds. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (pp. 273–308). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Byrne, M. W., Goshin, L., & Blanchard-Lewis, B. (2012). Maternal separations during the reentry years for 100 infants raised in a prison nursery. Family Court Review, 50(1), 77–90.

Byrne, M. W., Goshin, L. S., & Joestl, S. S. (2010). Intergenerational transmission of attachment for infants raised in a prison nursery. Attachment & Human Development, 12(4), 375–393.

Carson, E. A. (2018). Prisoners in 2016. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. Center for the Study of Social Policy. (n.d.). Strengthening Families protective factors framework. Source link

Charles, P., Kerr, M., Wirth, J., Jensen, S., Massoglia, M., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2020). Lessons from the field: Developing and implementing an intervention for jailed parents and their children. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Charles, P., Muentner, L., & Kjellstrand, J. (2019). Parenting and incarceration: Perspectives on father-child Involvement during reentry from prison. Social Service Review, 93(2), 218–261.

Christian, J., Mellow, J., & Thomas, S. (2006). Social and economic implications of family connections to prisoners. Journal of Criminal Justice, 34(4), 443–452.

Cobbina, J. E., Huebner, B. M., & Berg, M. T. (2012). Men, women, and postrelease offending: An examination of the nature of the link between relational ties and recidivism. Crime & Delinquency, 58(3), 331–361.

Durose, M. R., Cooper, A. D., & Snyder, H. N. (2014). Recidivism of prisoners released in 30 states in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Eddy, J. M., & Poehlmann, J. (2010). Children of incarcerated parents: A handbook for researchers and practitioners. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Folk, J. B., Tangney, J. P., & Stuewig, J. B. (in press). A longitudinal examination of women’s criminal behavior during the seven years after release from jail: Implications for children and families. In J. Poehlmann-Tynan & D. H. Dallaire (Eds.), Incarcerated mothers and their children: Separation, loss, and reunification. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Briefs.

Fontaine, J., Cramer, L., & Paddock, E. (2017). Encouraging responsible parenting among fathers with histories of incarceration. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.

Freudenberg, N., Daniels, J., Crum, M., Perkins, T., & Richie, B. E. (2005). Coming home from jail: The social and health consequences of community reentry for women, male adolescents, and their families and communities. American Journal of Public Health, 95(10), 1725–1736.

Glaze, L. E., & Maruschak, L. M. (2008). Parents in prison and their minor children. Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (NCJ222984). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Goshin, L. S., Byrne, M. W., & Henninger, A. M. (2013). Recidivism after release from a prison nursery program. Public Health Nursing, 31(2), 109–117.

Goshin, L. S., & Sissoko, D. R. G. (in press). Redefining motherhood: The process of mothering under community supervision. In J. Poehlmann-Tynan & D. H. Dallaire (Eds.), Incarcerated mothers and their children: Separation, loss, and reunification. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Briefs.

Kaeble, D., & Bonczar, T. P. (2016). Probation and parole in the United States. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Kaeble, D., & Cowhig, M. (2018). Correctional populations in the United States, 2016. NCJ 251211. Washington, DC. Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Kerr, M., Charles, P., Massoglia, M., Wirth, J., Jensen, S., Fanning, K., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2020). Development and implementation of a multilevel, multidisciplinary intervention to enhance visits between incarcerated parents and their children. Manuscript submitted for publication.

La Vigne, N. G., Brooks, L. E., & Shollenberger, T. L. (2009). Women on the outside: Understanding the experiences of female prisoners returning to Houston, Texas. Retrieved from the Urban Institute

La Vigne, N., Davies, E., Palmer, T., & Halberstadt, R. (2008). Release planning for successful reentry. A guide for corrections, service providers, and community groups. Retrieved from Urban Institute source link

La Vigne, N. G., Naser, R. L., Brooks, L. E., & Castro, J. L. (2005). Examining the effect of incarceration and in-prison family contact on prisoners’ family relationships. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 21(4), 314–335.

McKay, T., Comfort, M., Lindquist, C., & Bir, A. (2019). Holding on: Family and fatherhood during incarceration and reentry. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Murphey, D., & Cooper, P. M. (2015). Parents behind bars: What happens to their children? Bethesda, MD: Child Trends.

Naser, R. L., & La Vigne, N. G. (2006). Family support in the prisoner reentry process: Expectations and realities. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 43(1), 93–106.

National Reentry Resource Center. (2020). Reentry mythbusters. Retrieved from source link

Poehlmann, J. (2005a). Children’s family environments and intellectual outcomes during maternal incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1275–1285.

Poehlmann, J. (2005b). Representations of attachment relationships in children of incarcerated mothers. Child Development, 76, 679–696.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., Burnson, C., Weymouth, L. A., & Cuthrell, H. (2017). Attachment in young children with incarcerated fathers. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 389–404.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., Cuthrell H., Weymouth L., Burnson C., Frerks, L., Muentner, L.,…Shlafer, R. (in press). Multisite randomized efficacy trial of educational intervention for young children with jailed fathers. Development and Psychopathology.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Eddy, J. M. (2019). A research and intervention agenda for children with incarcerated parents and their families. In J. M. Eddy & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds.) Handbook on children with incarcerated parents (2nd ed.; pp. 353–371). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., & Pritzl, K. (2019). Parent-child visits when parents are incarcerated in prison or jail. In J. M. Eddy & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds.), Handbook on children with incarcerated parents (2nd ed., pp. 131–147). Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Poehlmann-Tynan, J., Runion, H., Burnson, C., Maleck, S., Weymouth, L., Pettit, K., & Huser, M. (2015). Young children’s behavioral and emotional reactions to Plexiglas and video visits with jailed parents. In J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Ed.) Children’s contact with incarcerated parents (pp. 39–58). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Runion, H. M. (2014). Mothers and the reentry process: Planning for reunification after incarceration. (Master’s thesis.) University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Sawyer, W., & Bertram, W. (2018). Jail will separate 2.3 million mothers from their children this year. Prison Policy Initiative. Retrieved from source link

Scott, C. K., Grella, C. E., Dennis, M. L., & Funk, R. R. (2016). A time-varying model of risk for predicting recidivism among women offenders over 3 years following their release from jail. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 43(9), 1137–1158.

Sesame Workshop. (2013). Little children, big challenges: Incarceration. source link

Shlafer, R., Hindt, L. A., & Saunders, J. B. (2020). “No one has ever asked me if I’m a dad”: Supporting families in the context of incarceration through community-university-corrections partnerships. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 40(4), 14–21.

Shlafer, R. J., Davis, L., Hindt, L., Weymouth, L., Cuthrell, H., Burnson, C., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2020). Fathers in jail and their minor children: Paternal characteristics and associations with father-child contact. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 791–801.

Skora Horgan, E., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2020). Mediated moments matter: In-home video chat between young children and their incarcerated parents. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Spjeldnes, S., Jung, H., Maguire, L., & Yamatani, H. (2012). Positive family social support: Counteracting negative effects of mental illness and substance abuse to reduce jail ex-inmate recidivism rates. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(2), 130–147.

Travis, J. (2005). But they all come back: Facing the challenges of prisoner reentry. Washington DC: The Urban Institute Press.

Turney, K. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences among children of incarcerated parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 89, 218–225.

Turney, K., & Haskins, A. R. (2019). Parental incarceration and children’s well-being: Findings from the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study. In J. M. Eddy & J. Poehlmann-Tynan (Eds.), Handbook on children with incarcerated parents (2nd ed., pp. 53–64). Cham: Switzerland: Springer.

Visher, C. A. (2013). Incarcerated fathers: Pathways from prison to home. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 24(1), 9–26.

Wakefield, S., & Wildeman, C. (2018). How parental incarceration harms children and what to do about it. National Council on Family Relations, 3(1), 1–6.

Waters, E., & Deane, K. E. (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-Methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1–2, Serial No. 209), 41–65.

Western, B. (2018). Homeward: Life in the year after prison. New York, NY:Russell Sage Foundation.

Wildeman, C. (2010). Paternal incarceration and children’s physically aggressive behaviors: Evidence from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. Social Forces, 89(1), 285–309.

Wildeman, C., Haskins, A. R., & Poehlmann-Tynan, J. (2017). When parents are incarcerated: Interdisciplinary research and interventions to support children. Bronfenbrenner Series on the Ecology of Human Development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books.

Yeary, J., Zoll, S., & Reschke, K. (2012). When a parent is away: Promoting strong parent–child connections during parental absence. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 32(5), 5–10.

Yocum, A., & Nath, S. (2011). Anticipating father reentry: A qualitative study of children’s and mothers’ experiences. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 50(5), 286–304.

Zeng, Z. (2019). Jail inmates in 2017. April 2019, NCJ 251774. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

ZERO TO THREE. (n.d.). Military Family Projects. Retrieved from source link