You Zhou, ParentChild+ National Center, Mineola, New York; Arexy Bravo Stewart, Lake Worth West Resident Planning Group ParentChild+, Palm Beach County, Florida; Jand acquelyn D. Robinson, Public Health Management Corporation ParentChild+, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Abstract

ParentChild+ is a national home visiting program dedicated to bridging the opportunity gap for families in marginalized communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the program worked more closely than ever with families and family care providers with young children to ensure they had the necessary tools and resources to support their children to thrive in school and life. This article documents how the frontline workers, despite all the challenges they faced during the pandemic, played a critical role in engaging families and communities and mitigating the devastating effects of the pandemic and its aftermath.

ParentChild+ (formerly known as the Parent-Child Home Program) is an early childhood home visiting program addressing the long-existing opportunity gap in low-income communities by supporting families with young children and home-based child care providers with information and tools to promote children’s healthy development before they enter school. With more than 50 years of implementation experience, the National Center partners with school districts, social service agencies, housing authorities, immigrant aid and faith-based organizations, and other community-based organizations, working in 16 states, Canada, Ireland, UK, Bermuda, and Chile. In 2020, ParentChild+ worked with almost 9,000 families and 180 family child care (FCC) providers caring for 1,400 families. The program reaches isolated caregivers with children from 16 months to 4 years old in historically marginalized communities.

ParentChild+’s most valuable assets are the early learning specialists (ELSs), the home visitors, who typically share a community, linguistic, and/or cultural context with the families they support. In 2020, we had 799 ELSs and 292 supervisors in our network. In ParentChild+’s One-on-One model, ELSs work individually with families, providing a total of 92 half-hour home visits that are delivered twice per week. Each week, they bring a gift of a book or educational toy, facilitating reading, conversation, and play activities designed to enhance parent–child interaction and develop language, literacy, numeracy, and social–emotional skills. In the FCC model, ELSs provide innovative, culturally and linguistically appropriate professional development and enrichment for FCC providers through 24 weeks of twice-weekly 45-minute visits, 12 books and toys, and an array of art supplies for creative, age-appropriate activities. The shared bonds and frequent visits build long-term trusting relationships enabling ELSs to connect families and providers with resources including housing, food, medical, and educational supports.

Frontline Workers During the Public Health Emergency

There is extensive research documenting the value of home visiting in supporting families with young children, providing prevention and intervention services, connecting families to resources and ultimately improving outcomes for children pre- pandemic (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2019; National Home Visiting Resource Center, 2020, 2021). During the pandemic, it became even more essential for families to receive support, as they faced social isolation and economic hardship, and evidence indicates increases in child abuse (Seddighi et al., 2021), domestic violence (Kofman & Garfin, 2020; Leslie & Wilson, 2020) and substance abuse (Taylor et al., 2021). For many families, home visiting was a lifeline during the pandemic (Williams et al., 2021).

Communities of color and low-income immigrant communities, already struggling under the huge weight of systemic racism, have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. The over- representation of people of color in infections, hospitalizations, and deaths (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; United States Census, 2020) has called out the health impacts of racism. These are the families and communities ParentChild+ works with. In 2020, the program worked with families from 118 countries speaking more than 34 languages. Of the families served, 91% are non-white (38% Hispanic and/or Latino families, 33% Black and/or African American families, and 12% Asian families).

The trusting relationships between ELSs and families and the program’s strong connections to community resources enabled the staff to swiftly adapt program delivery to respond to families’ changing needs during the crisis. Aligning with the role of home visiting during a public health emergency outlined by the Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA Maternal & Child Health, 2021), and adapting to the new remote environment along with other home visiting models (National Alliance of Home Visiting Models, 2021), ELSs expanded their scope to stay connected to families.

What ParentChild+ Learned From the Field

The ParentChild+ Research department has been collecting field data to understand COVID-19’s impact on ELSs and families and to identify the strategies ELSs developed to stay engaged with families as the program pivoted to virtual visits. This section summarizes key findings from feedback groups conducted in June 2020 and surveys collected in December 2020. The findings parallel those from other home visiting studies (Bultinck et al., 2020; Child & Family Research Partnership, 2020; Marshall et al., 2020).

In June 2020, the program conducted feedback groups with 30 ELSs from Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Washington on their experiences. The groups shared that health and safety fears, and anxiety and uncertainty over how long the situation would last, tremendously impacted both families and ELSs. But despite the challenges and chaos of the early pandemic phase, the organization and partnering agencies navigated through uncertainties and made the best decisions they could for staff and families. Following the guidelines from the ParentChild+ National Center, their own agencies, cities, and states, each site took immediate action. Some chose to shut down completely until the situation became more clear, some were able to deliver program materials and essentials to families before closing, and others adapted all virtual tools immediately to connect with families. For families who were not able to do video calls, sites did phone call check-ins, texted, and dropped off materials. They did anything they could to stay connected with families and make resources available to them.

Communities of color and low-income immigrant communities, already struggling under the huge weight of systemic racism, have been disportionately impacted by COVID-19. Photo: Ringo Chiu/shutterstock

Initially, the virtual visits with families were reported to be challenging with mixed reactions from the staff, ranging from “50% successful rate,” “complicated and confusing sometimes,” to “not working at all with children.” The shift from being a 100% in-person program was challenging. As one ELS noted, the program was not designed this way, and they were modifying it as they went along, learning how to do it virtually. Still, the ELSs found strength and inspiration in the situation and have kept moving forward. They reported working together even more, both at their sites and across communities. They shared what was working and not working, including virtual resources in different languages. For example, one site recorded video clips of ELSs reading books in Arabic, and another site that did not have the language resources was able to share the videos with some of their families. As an ELS put it “we have great teamwork with each other and appreciate each other’s strengths.”

ELSs developed creative strategies to effectively engage families. ELSs incorporated their home life into the visits, introducing their children and pets or drawing connections between things in their houses and the things in a family’s home, such as kitchen items. One ELS made cardboard dinosaurs, farm animals, and undersea creatures to create different themes in her yard to engage with the children. Another ELS sometimes included her 5-year-old son in the virtual visit to interact with the program child. As she described, “It was almost like a playdate for both of them. My son got a kick out of it because he felt like he was going to work with me.”

What has remained the same in virtual visits is how ELSs continue to put families at the center. As the pandemic destabilizes families’ lives, ELSs have been anchors for families. Some reported connecting with families even more often, finding that frequent check-ins or virtual visits reassured families that “somebody is thinking about them and supporting them.” They also reported that listening and connecting with parents was most important in these check-ins. One ELS observed that sometimes conversations with parents could last an hour, talking about what the families needed, saying “They need me more than the child does.” This observation reflected the real needs of families during these unprecedented times. Parents needed emotional and social support as their concerns over uncertainty, fear of infection, unemployment, and their intense loneliness grew.

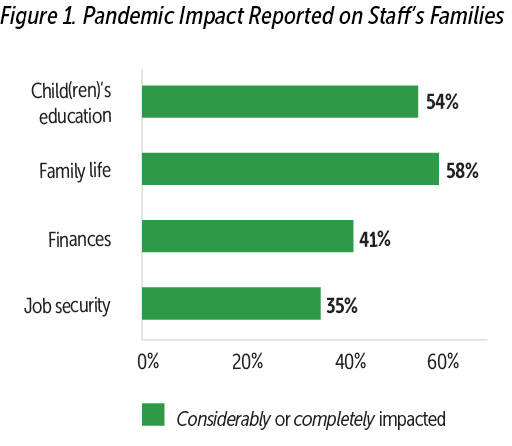

In December 2020, our research team launched an online survey to understand the wider impacts on ELSs and their communities and their perspectives on virtual visits. Overall 131 respondents from partner agencies nationwide responded. As ELSs are often from the same communities as the families, they experienced similar health, economic, and child care struggles. Of the respondents, 71% knew someone who had tested positive for COVID-19, including themselves, close friends, or relatives. A large number of them reported being considerably or completely affected by the pandemic in terms of their own children’s education, family life, finances, and job security (see Figure 1). In the communities they live in, early childhood education centers (77%), school districts (92%), and medical offices (70%) were considerably or completely impacted. Key stressors ELSs faced were the additional demands and challenges of virtual visit work, including struggling to build personal connections virtually with some families (52%) and families’ limited/lack of access to devices, applications, or Internet connections (23%).

With great strength and commitment, ELSs navigated these challenges and continued their work connecting with families. They conducted visual visits, texts, and calls; delivered program materials and essential supplies; sent regular newsletters; and connected families with resources. Based on the survey data, compared to the initial uncertainties transitioning to virtual visits, 90% now report a positive perspective on virtual visits, identifying the strengths of virtual visits as scheduling flexibility, watching families lead visits more, and being more creative with materials and curriculum. Moreover, virtual visits did not reduce visit frequency. Overall, 57% of ELSs report the same frequency as in-person visits and 39% report more frequent visits with families than when they were in person. This finding is congruent with increased demand for home visiting since March 2020 and the uptick in visit frequency reported by the national initiative Aligning Early Childhood and Medicaid led by Center for Health Care Strategies (Yard, 2020). The data also show that the biggest changes in visit content are adults relying on staff more for accessing resources (44%) and to listen to their concerns (43%). These responses reflect the growing mental health crisis fueled by COVID.

Feedback group and survey data illustrate how ELSs have adapted to virtual work during the pandemic. It has been a challenging process, however, ELSs have remained positive and confident while continuing to engage and support families. In the following two sections, two ELSs share stories of their personal experiences.

As the World Paused, We Didn’t Stop: A Journey in Focus, Action, and Passion

Arexy Bravo Stewart

It has been a year since, unexpectedly, we started living a life defined by many uncertainties. The journey has been different and it has highlighted what was inside each individual. January and February 2020 welcomed home visits, more success stories, assessments, training, meeting, driving here and there, cooking, and quality time with family.

But day after day things started to change! The news announced an unknown health situation spreading dangerously around the world. The unimaginable became the norm: social distance, isolation, quarantine, masks, shortages of basic items and food, people were asked to stay home…What is happening? How to avoid the danger? Why are the stores now empty? Why are the schools deserted? No children in the playground… Is this real? The desolation tried to paralyze me, but I turned and focused on what was still there immovable: nature, faith, love…Why does it feel like the world was taking a break? Are the days going on a loop? Because…sorry, that is not an option. Essential jobs can’t stop, and some things can’t wait. We must go on! I have been serving mostly the Hispanic community in Palm Beach County, and their needs were only going to increase.

It was time to reinvent what already existed. ParentChild+ had to continue reaching and being there for our families, no matter what! There were so many questions: How to deliver the books and toys? How to conduct the sessions without going to the home? Do families have access to technology? Computers? Wi-Fi/Internet? How to engage caregivers and children without being physically present in their homes? Are caregivers emotionally available for sessions or are they understandably busy wondering how to meet their basic needs? How would caregivers as well as early learning specialists (ELSs) juggle their professional responsibilities with each individual’s personal challenges?

There was no time to adapt to these changes. I just had to adjust, accept, be flexible, and importantly, enjoy the process, because one thing I know for sure, if I want to reflect and transmit joy, love, and support to families and children, I have to be full of these things. I quickly realized that I had two choices, to resist and complain about these unprecedented situations, or to find a way to accomplish my goals with a positive mindset. Therefore, I did!

The first step was delivering the books, toys, and everything families would need to be able to continue participating in the sessions. I packaged everything needed for the 15 families I serve and got ready to deliver. However, I knew that many of the families were worried, scared, wondering about their future, so I wanted to bring hope and let them know that we really care. I wanted them to feel special! So I got finger paint, heart-shaped foam, and did something a little different: I decorated the car with happy faces, hearts, and the message: “DELIVERING HAPPINESS”, ParentChild+.

The first step was delivering the books, toys, and everything families would need to be able to continue participating in the sessions. I got finger paint, heart-shaped foam, and did something a little different: I decorated the car with happy faces, hearts, and the message: “DELIVERING HAPPINESS”, ParentChild+. Photo: Lake Worth Resident Planning Group ParentChild+;

The smiley faces, the eyes wide shining with joy, the excitement shown by children as well as their caregivers was such a satisfying experience. Other drivers even honked at me and smiled as I drove from one family to another. The comments of the caregivers stating how they felt that they were not alone, that things were going to work out, made me realize that my wish came true: not only was I delivering the program materials but I was delivering joy, love, and hope. Families were supplied with everything they needed to complete the sessions.

Next step was to shift from in-person visits to remote sessions. With genuine enthusiasm, I contacted each of the families I was serving and shared the good news: Sessions will continue, twice a week as usual, and we will continue to learn, read, play, and interact. I will be here to support you, to listen, to observe, to care. I will not be there physically, I explained, but I will be 100% there. The video calls will be “like a bridge” that will keep us together, no matter what. Like any other transition, it was different, but different did not mean less effective, less fun, or less engaging. I continued to focus on my belief: love transcends every situation, and I was determined to find all the amazing benefits of being able to connect remotely. Therefore, I did!

Sessions were happening in a very special way! I made sure that when the caregiver and the child(ren) answered each video call, they would find caring eyes, a friendly smile, a helping hand, and an ELS to help them fill each video call with fun learning, positive comments, hope, encouragement, and the support that they needed to go on in the midst of not only the pandemic, but also all of the economic struggles it was causing.

Delivering program supplies, a smile, and reassurance that early learning specialists were there for families. Photo: Lake Worth Resident Planning Group ParentChild+;

I emphasized the advantages of virtual learning to caregivers, such as staying safe during this social distancing period, being able to participate from any place, building their confidence to manage technology, easing any insecurity about their knowledge and capacity to lead the sessions, implementing strategies to enhance the interaction between caregiver and child, and the flexibility to support caregivers who now also had other children doing school remotely at home.

I noticed how families were very engaged. They were looking for the day and time to participate in the virtual sessions. Caregivers would express how thankful they were being part of the program, when otherwise they would be in total isolation. Caregivers’ self-confidence bloomed brighter than ever! Each session was a display of creativity. Caregivers took the lead. They really saw that they are the first and most important teacher of their children. The interaction between caregiver and child was delightful to watch. Cancellations of sessions dropped. Families were attending the virtual sessions from all over the place, no matter what!

One family participated in their remote visits while staying in North Carolina! Another caregiver participated in the sessions from a hotel room where she was spending the quarantine with her son, after testing COVID positive. I was so surprised and proud of this family, thinking that as they were quickly packing a few things to be isolated, they had included what they needed for the session, saying,“We forgot some things, but not the Magic Noodles for today’s activity.” We completed a session that was an oasis in a deserted moment in this family’s life. They recuperated, returned home, and are still enjoying being part of ParentChild+.

Unfortunately, COVID hit some families harder. One of my caregivers, a mother of three, called to let me know she was not going to be able to participate in the session that Wednesday, as she tested positive and was admitted in the hospital. Once again, my admiration went to the caregivers whose responsibility and commitment goes beyond the imaginable. I wished her well that day, and promised to call her back in 2 days to follow up. She was born in the same country as me…I guess that influenced the special connection between the family and me. During the in-person visits as well as the remote sessions, I remember seeing the Venezuelan flag hanging on the wall and listening to the familiar accent. I did call her to check on her. I left a message that Friday, but she won her wings the day after we talked… My client’s father is so grateful that her daughter is in the program… “It is one thing, at least, that will not change in the life of my daughter,” he said, “the sessions and being able to build memories one class at a time.” After a period of grieving, this family is making an effort to recuperate emotionally, and being in ParentChild+ is one of their favorite tools to accomplish this goal. It is still hard to believe that this young mom is no longer here, but again, I had to find something to hold tight to, so I could genuinely be able to smile, play, and support this family as my heart cried. So I did! The program child’s sweet face, the interaction between her, her sister and their dad, now, for the first time participating in the session, and their smiles during every session, are a reminder that an angel is watching over her, over us, and that love transcends everything!

Changes could be challenging, but it is during adversity when we must be the strongest. We must find beauty in every moment. I believe our will to continue serving the most vulnerable families—with passion, love, and flexibility—turned this unexpected and uncertain experience into one that will forever make us more resilient, stronger, and resourceful, and we will definitely value more what many times we took for granted.

Surviving Through Resiliency

Jacquelyn D. Robinson

How do you begin to support families who were already focused on surviving their current circumstances prior to the pandemic? While ensuring that you are also self-supporting effectively? In my experience there is no right or wrong way, and no plan is ever sufficient to address all their needs. As an early learning specialist (ELS), my coworkers and I are the frontline for program and family outcomes. The program works because we work it by connecting with families in circumstances that we understand and from positions that we have experienced, while focusing on not only their strengths but our own. Working during the pandemic increased an endurance that was needed to continue being present for families and self.

Once the quarantine was in effect there was much fear and concern across the program and community. Our program immediately ceased home visits. At this time, I was already through the first year of the program with my families, we had relationships and routines in place. Though we were not conducting in-person visits, that did not eliminate the “connection” that I was for them. I had families losing income, with children home full-time who needed services, concerned about food resources—all situations which I now shared for my personal welfare. I was concerned for some of my families’ mental health and wondered how they would find the endurance to push through while already living in survival mode. The resources and information I found for myself, I shared with families across our team. Throughout the weeks, families and I communicated via telephone on how we were maintaining our families and shared tactics on managing teenagers, toddlers, and self-care. Strategies like including young children in household tasks, giving teens a structured space in which they could make decisions for themselves (not setting a time for homework to be done, so long as it was completed that day); even the minor things like taking a shower and using your favorite lotion as impactful self-care. It was those phone calls and shared experiences that kept us both sane and connected, during a very uncertain time.

As the weeks of quarantine became more restrictive, and check-ins became more frequent and concerning, our team felt we had to do more. I had learned from talking with families that child services was unresponsive to calls for help; I informed my families of the chain of command and how to follow it through the Human Services network—as well as informed my supervisor in our next meeting. During a team meeting, it became evident that multiple basic family needs were not being met and help was at an all-time low. We did what we do best, “Hit the pavement”; we dropped off supplies to families’ homes and practiced social distancing. Everything from food, diapers, books, gift cards, utility vouchers, and tablet computers to stay in touch with loved ones were donated to our families in need. The outpouring of appreciation for just being consistent, listening, and “showing up” was rewarding. But we could not stop there.

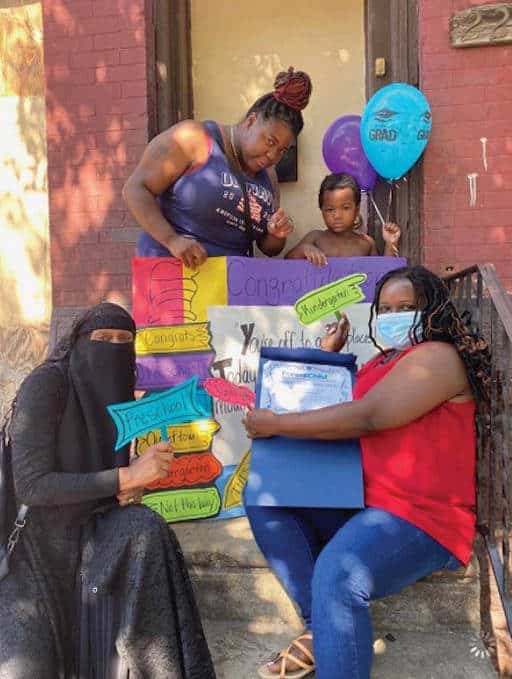

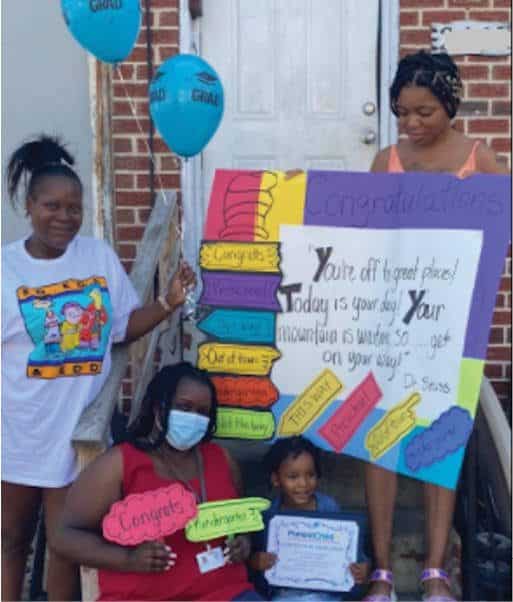

Because of the pandemic, we had to cancel graduation plans. As an ELS, I get to help people recognize their strengths, overcome challenges, and watch parents and their children build skills while sharpening my own. As program participants and ELS partners, we grow together—that growth must be celebrated. Within my team we got creative: we crafted large signs and bought treats and toys to create graduate gift packs for children. We drove to each home and took the time to celebrate each child right in front of their home! The families loved it and so did we. One mom was so overwhelmed during our drive-by celebration that she got emotional and cried. For her it had been a time of great stress, uncertainty, and insecurity. The motivation that I gained from being creative and helping others helped me help myself and my family.

Within my team we got creative: we crafted large signs and bought treats and toys to create graduate gift packs for children. We drove to each home and took the time to celebrate each child right in front of their home! Photo: Lake Worth Resident Planning Group ParentChild+;

These achievements of surviving through resilience supplied me with real stories and facts to encourage and motivate the next families that would be assigned to me. These new families would be embarking on virtual visits without first having an in-person meeting or the experience of in-home visits. Yet, they would have the full advantage of being in the driver’s seat for their child’s virtual learning from the start. Moving into the next phases of virtual visits didn’t look as grim as what was going on around us. Especially since I had program support and adapted the mindset that “It’s okay, to not be okay. And work on being present in the moment.” This is the mindset that I share with families and coworkers, making for a less stressful way to just play and learn; even for a few minutes.

Families loved our front steps graduation celebrations, honoring parents and children for the amazing work they had done under unimaginable conditions. They were important moments of joy for families and staff. Photo: Lake Worth Resident Planning Group ParentChild+

Summary

While grappling with the difficulties and challenges of the pandemic, home visiting programs like ours will continue to use deep community roots and trust relationships to help families navigate economic, social, and psychological challenges during and beyond the current crisis.

Parents needed emotional and social support as their concerns over uncertainty, fear of infection, unemployment, and their intense loneliness grew. Photo: RW Jemmett/shutterstock

In the meantime, we would like to sincerely thank our devoted frontline workers who with great optimism and creativity are working tirelessly to meet the changing needs of families and communities. Lastly, we urge policymakers at all levels to work together with us to ensure sufficient resources and support are allocated to home visiting staff who are continuing and expanding the amazing work they have always done.

Authors

You Zhou, PhD, is a research scientist at the Research & Evaluation Department at ParentChild+ National Center and a postdoctoral research fellow at New York Psychoanalytic Society & Institute. She is from China. Dr. Zhou completed bachelor’s of science in social psychology, a master’s of science in psychoanalytic developmental psychology and later her doctorate at University College London in the UK. She has extensive research and clinical experience working with underserved communities. Dr. Zhou’s interests include attachment research and application, as well as evaluating and improving evidence-based practice.

Arexy Bravo Stewart is an early learning specialist with ParentChild+. Arexy graduated with honors, receiving a bachelor’s degree from the University of Nueva Esparta, in Venezuela, her country of origin, where she gained more than 10 years of experience in pedagogy, working as a school teacher at different levels. Her extensive experience and expertise consists of more than 20 years devoted to contributing to help children and families, and it is continuing to grow, as she has worked for ParentChild+ since 2009, serving with passion the Hispanic community in Palm Beach County, Florida.

Jacquelyn D. Robinson was raised in the Uptown section of Philadelphia where she was instilled with a value system from influential people, personal trials, and trauma that helped mold her motivation to be better than her circumstances. She is a proud mother and seasoned advocate for education and personal growth; much of her experience derives from serving the endangered youth and homeless populations in Philadelphia, as well as working in early education. Helping others better themselves has always been a passion and tool she used in both her personal and professional life to advocate for what was right. Ms. Robinson has committed to using her talented gifts to act upon her passion to educate, inform, and inspire. One person at a time.

Suggested Citation

Zhou, Y., Stewart, A. B., & Robinson, J. D. (2021). ParentChild+ home visiting staff: Stories of resilience during COVID-19. ZERO TO THREE Journal, 41(4), 42–49.

References

Bultinck, E., Haas, M., Hegseth, D., Hilty, R., Crowne S., & Chohen, R. (2020) Understanding the needs of California’s home visiting workforce during COVID-19. link

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). COVID-19 racial and ethnic health disparities. link

Child & Family Research Partnership. (2020) Texas home visiting: Assessing early experiences with COVID-19 (Report No. B.042.1020). link

HRSA Maternal & Child Health. (2021, February 4). Important home visiting information during COVID-19. link

Kofman, Y. B., & Garfin, D. R. (2020). Home is not always a haven: The domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S199–S201. link

Leslie, E., & Wilson, R. (2020). Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104241.

Marshall, J., Kihlström, L., Buro, A., Chandran, V., Prieto, C., Stein-Elger, R., Koeut-Futch, K., Parish, A., & Hood, K. (2020) Statewide implementation of virtual perinatal home visiting during COVID-19. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24, 1224–1230

National Alliance of Home Visiting Models. (2021). Rapid response virtual home visiting. link

National Conference of State Legislatures. (2019). Home visiting: Improving outcomes for children. link

National Home Visiting Resource Center. (2020). Home visiting primer. link

National Home Visiting Resource Center. (2021). Why home visiting? link

Seddighi, H., Salmani, I., Javadi, M. H., & Seddighi, S. (2021). Child abuse in natural disasters and conflicts: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 176–185.

Taylor, S., Paluszek, M. M., Rachor, G. S., McKay, D., & Asmundson, G. J. (2021). Substance use and abuse, COVID-19-related distress, and disregard for social distancing: A network analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 114, 106754.

United States Census. (2020). Quick facts District of Columbia. link

Williams, K., Ruiz, F., Hernandez, F., & Hancock, M. (2021). Home visiting: A lifeline for families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 35(1), 129–133.

Yard, R. (2020, Jun 25). The crucial role of home visiting during COVID- 19: Supporting young children and families. link